Guatemalan Immigrant Luisa Moreno Was Expelled From the U.S. for Her Groundbreaking Labor Activism

The little-known story of an early champion of workers’ rights receives new recognition

:focal(1842x640:1843x641)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9a/f7/9af7c303-2123-4800-89bf-88c06b05449e/luisa2.jpg)

“The distance, watching you in its black cloak, will not have the strength to separate us. . .” These wistful words, written in Spanish, appear in a 1927 poem entitled “La ausencia,” or “The Absence.” The author, Blanca Rosa López Rodríguez, was a 20-year-old news reporter in Mexico City, who had left her rigidly patriarchal Guatemalan homeland in search of a way to impact the world around her in her own right. Within three years, she would change her name to Luisa Moreno, cementing for the rest of her life la distancia between her and her disapproving family back home.

Rodríguez moved from Mexico City to New York City in 1928, seeking a fresh start in the so-called land of the free. What she found upon joining the labor force at a bleak industrial garment factory was that the United States had a long way to go before it could rightfully claim that title. Wages were paltry, hours were long and discrimination against nonwhites ran rampant. As the Great Depression took hold in 1930, Rodríguez rechristened herself and joined the roster of the Communist Party. Dedicated to workplace reform and women's rights, the Party, whose name would be irrevocably tarnished amid the paranoia of the Cold War, was at the time a perfect fit for an up-and-coming workers' rights champion. A woman on a mission, “Luisa Moreno” rose to become one of the most prominent and impactful labor activists in the nation.

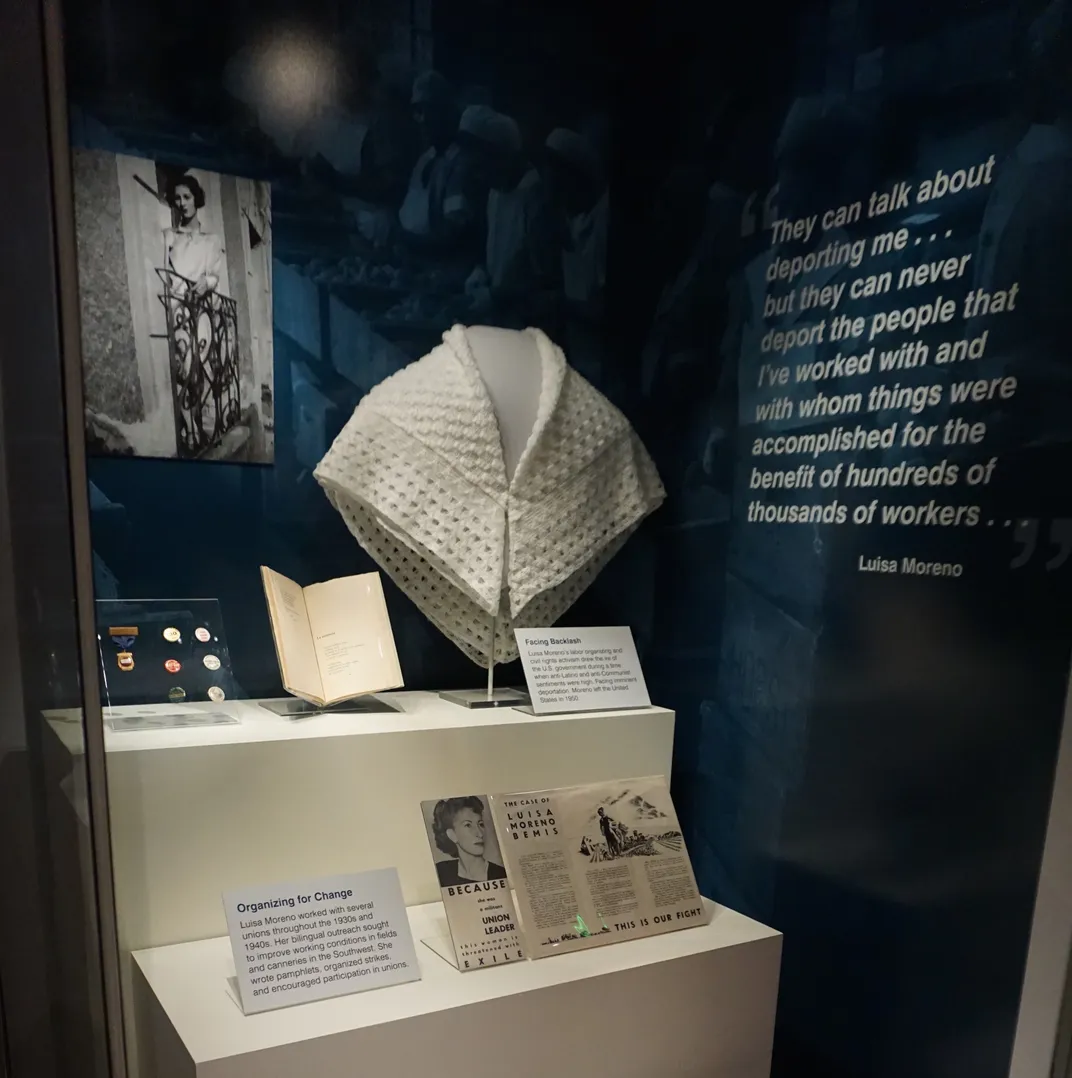

Moreno’s story is the focus of a new installation at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, a display case with interactive touchscreen panels that was added to the “American Enterprise” exhibition last week. The exhibition, which opened in 2015, unpacks the growth of industry in the U.S. since the country’s foundation. Yet behind the history of every business is the history of its workers, and curator Mireya Loza, who oversaw the installation of the new Luisa Moreno display, believes passionately that labor leaders in Moreno’s mold deserve inclusion.

“I think Moreno’s life story is a wonderful story—this is squarely American history of union organizing and civil rights,” Loza says. “In an exhibition on American enterprise, I thought it would be fantastic to think about workers. And she represented the interests of workers.”

Having participated in several strikes at the garment plant, Moreno quit to become a full-time advocate for immigrant laborers everywhere, signing on with the American Federation of Labor as an organizer in 1935. Traveling south to Florida, she rallied underpaid workers in the state’s sun-beaten tobacco fields. This was just the beginning.

Moreno soon pivoted to the Unified Cannery, Agricultural, Packing, and Allied Workers of America (UCAPAWA), a group closely affiliated with John L. Lewis’s Congress of Industrial Organizations (the AFL and CIO would not merge until 1955). Moreno became both the first woman and first person of Latin descent appointed to the CIO council, and in the early 1940s journeyed westward to help Californian food processing employees coalesce into unions.

“I think the biggest splash she made in terms of long-term impact was probably in Southern California,” Loza says, “not because she didn’t do fantastic work in other places, but because there she actually starts to create the Spanish-Speaking People’s Congress, which was a nice dovetail between her labor activism and civil rights work.” El Congreso de Pueblos de Hablan Española, as it was known in Spanish, was born at Moreno’s urging in 1938, and went on to become a vital outlet for Mexican-American voices, who used the organization efficaciously to lobby for protective legislation and reforms in housing and education.

Loza recounts Moreno’s run-in with contemporary labor leader Emma Tenayuca, a Mexican-American cut from the same cloth. On her way west, Moreno made a noteworthy stop in Texas. Having learned of Tenayuca’s efforts to protect migrant pecan sellers, Moreno lent a hand with activism in San Antonio.

“Tenayuca is a homegrown Tejana,” says Loza, who herself called the Lone Star State home for a time, “and you have Luisa Moreno, a figure from Guatemala, and Moreno assists Emma Tenayuca in her labor activism. And you have this moment where there’s two dynamic women leading this labor movement who collide in San Antonio, Texas.” Loza’s wide smile and rapid speech make her own admiration for these heroines readily apparent. “I just wish I could be a fly on the wall at that moment,” she says.

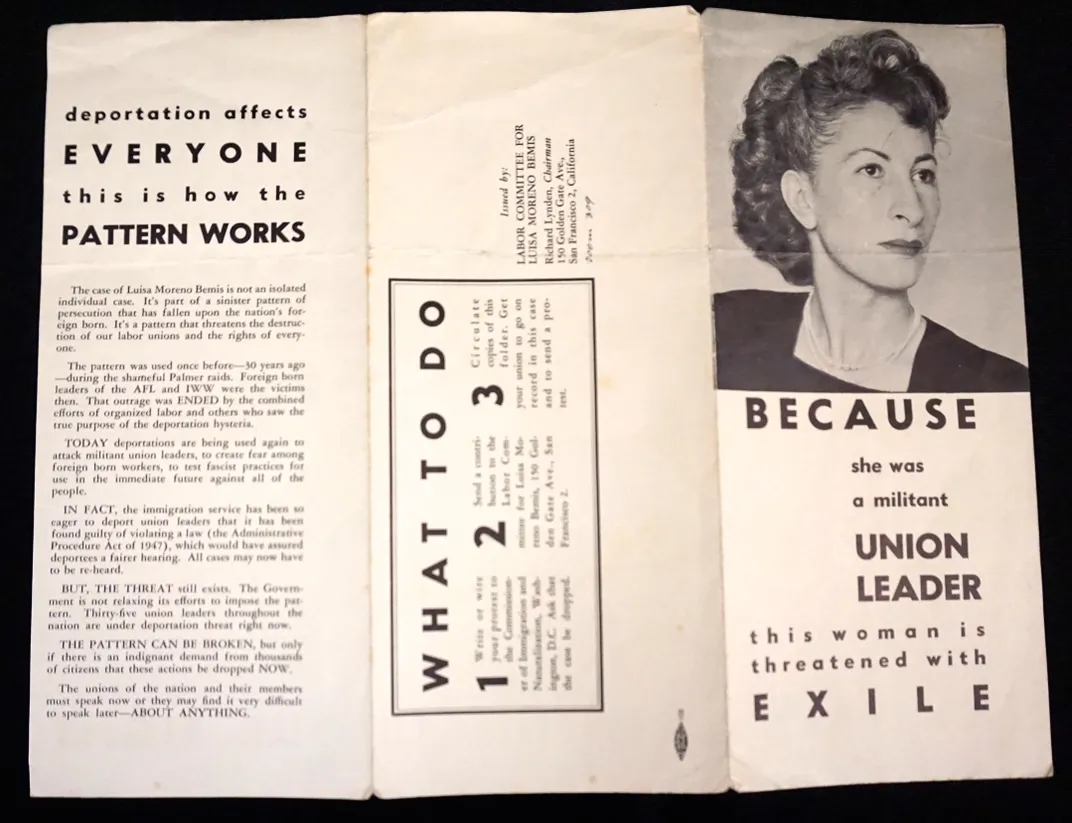

Moreno’s commitment to immigrant laborers endured across World War II. But in the postbellum “red scare” that marked the onset of America’s Cold War with the Soviet Union, Moreno’s workers’ rights campaign was tragically truncated. Increasingly unsympathetic toward activist immigrants, the federal government in 1950 concocted a warrant for Moreno’s immediate deportation, citing her association with the Communist Party as a threat to national security.

Rather than subject herself to the humiliation of forced removal, Moreno left the U.S. that November, returning to Mexico with her daughter Mytyl and her second husband, Nebraskan Navy man Gary Bemis. In time, the family made their way back to Moreno’s point of origin, Guatemala. When her spouse died in 1960, Moreno relocated temporarily to Castro’s Cuba. But it was Guatemala where the fiery labor leader passed away in November of 1994, the distancia between her and her birthplace finally erased.

“Often, when I think about her departure,” Loza says of Moreno’s expulsion from the U.S., “I think about all the talent and expertise, and all of that dynamic vision, that left with her.”

Moreno paved the way for the United Farm Workers, but is today nowhere near as well-known as those she inspired. “Oftentimes, we attribute Dolores Huerta and César Chávez as the beginning of labor activism and civil rights work,” Loza says, “but in fact, there are a lot of folks like Luisa Moreno” who made their successes possible. Moreno is an especially powerful example, Loza adds, in that she, unlike Huerta and Chávez, was not a U.S. citizen.

American Enterprise’s new display contains intimate mementos of Moreno’s life, artifacts donated to the Smithsonian by the labor activism historian Vicki Ruiz, who had herself received them as gifts from Moreno’s daughter, Mytyl. The display includes the book of poetry Moreno published in 1927, back when she was still Blanca Rosa López Rodríguez. It also features a widely distributed pamphlet railing against the prospect of her deportation, and an elegant white shawl that Moreno wore about her neck in the last years of her life.

Loza is looking forward to sharing these treasures with the American public, and in particular those of Central American heritage. “Moreno’s story shows us that the Latino civil rights story is not only a Mexican story, but that Central Americans also played a role,” Loza says. “And the aspect that she’s a woman, a woman from a different country, really makes me hope that the Central American community can see how they contributed to Latino civil rights.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)