Hamilton’s David Korins Explains What Makes the Smash Hit’s Design So Versatile

The renowned designer dishes about the new Hamilton exhibition, precision and metaphor on stage and how the turntables almost didn’t happen

:focal(2617x1575:2618x1576)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/38/ff/38ffe43d-fabd-415b-aba8-f44c2ec638e3/_dsc0003-revised.jpg)

He contrived the tech-heavy set for the Broadway hit Dear Evan Hansen, the eye-popping playhouse of The Pee-Wee Herman Show stage run and the complicated maze that comprised TV’s Grease: Live. He’s done concert sets for everyone from Kanye West to Mariah Carey. But David Korins is best known for concocting a set for one of the most successful musicals of all time, Hamilton.

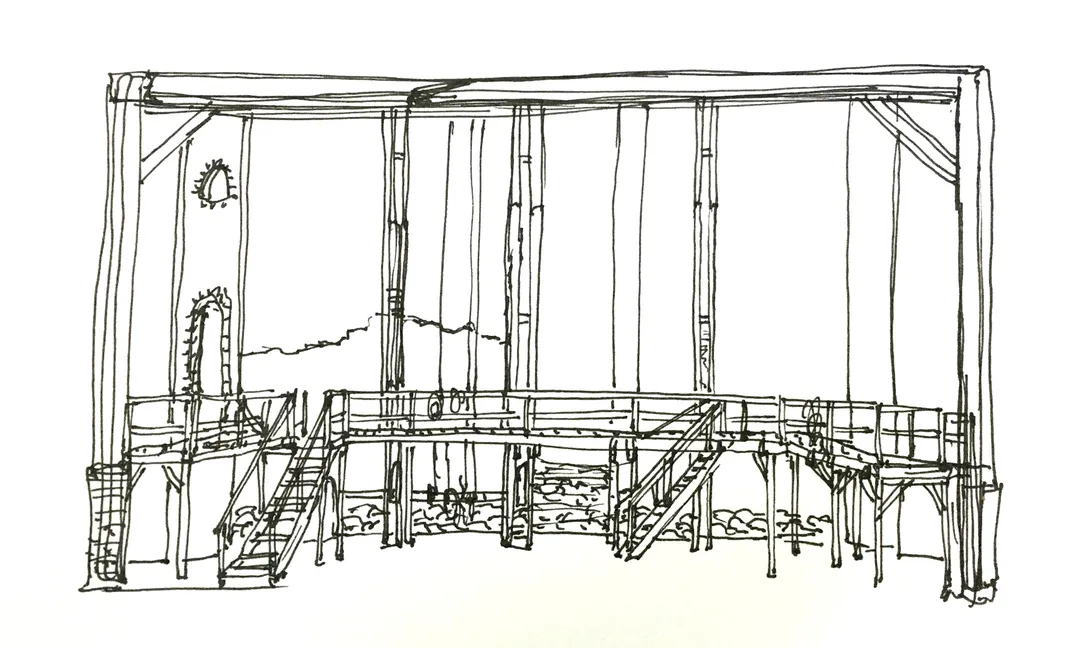

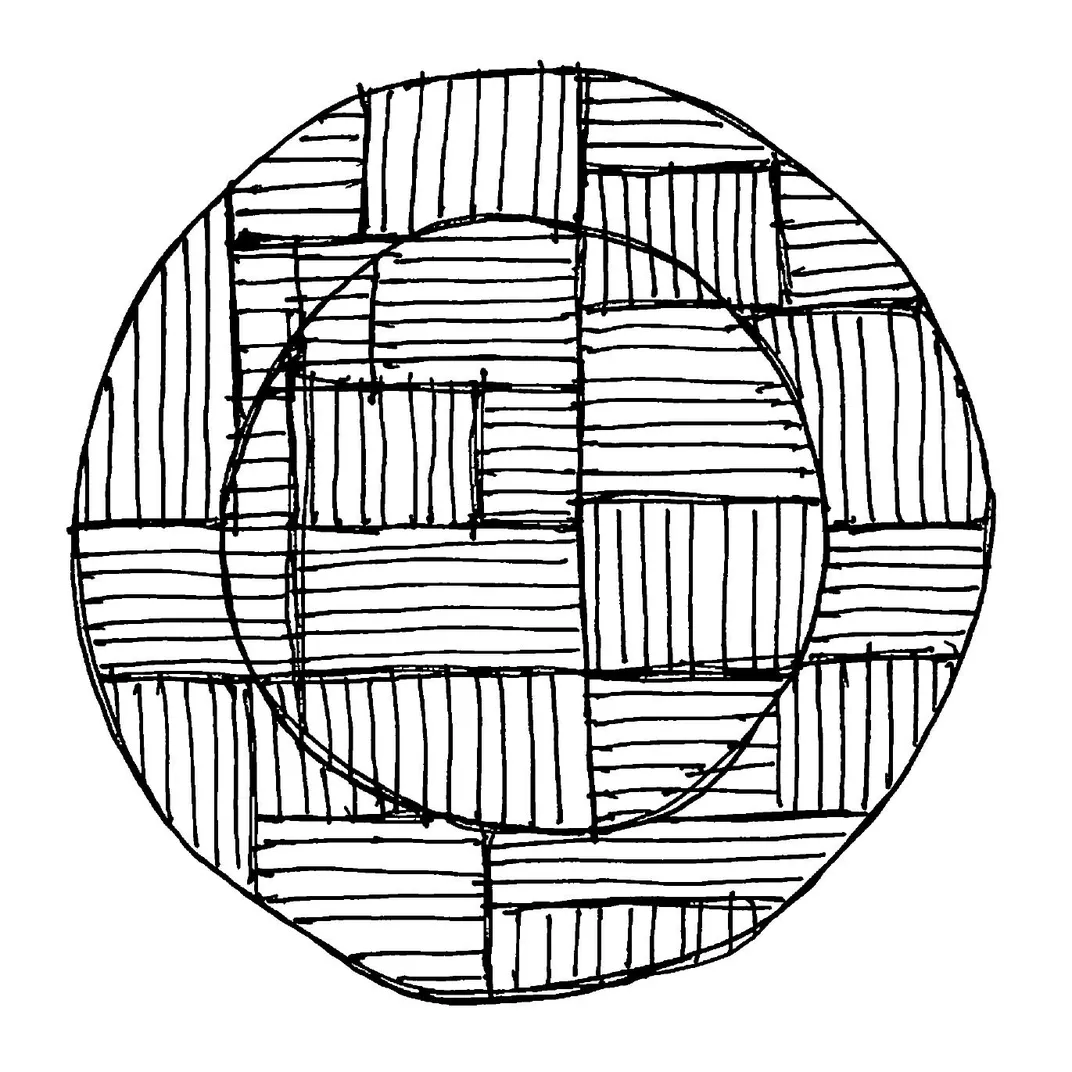

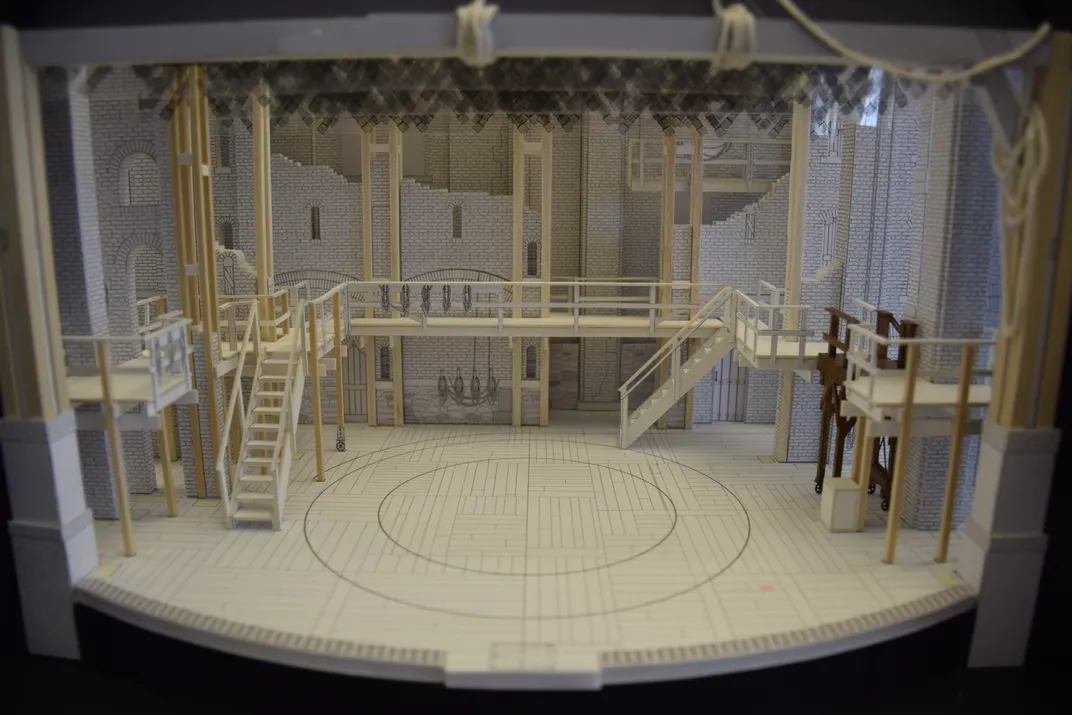

His striking design—involving a double turntable, a second level catwalk, scaffolding and ropes that call to mind the ships that brought the Founding Fathers to America—framed the popular Tony Award-winning work from Lin-Manuel Miranda that has brought sellout crowds to New York City since the show opened three years ago.

Before a much-anticipated three-month run by the Hamilton national touring company opens at the Kennedy Center June 12, Korins, 41, comes to Washington, D.C. for a sold-out appearance with the Smithsonian Associates program on May 31 titled Designing the World of Hamilton.

We talked to him about that event, how he devised the set and how he’ll expand upon it in a newly announced project, “Hamilton: The Exhibition” in Chicago later this year. This conversation was edited for clarity and length.

You’re appearing at the Smithsonian two weeks before Hamilton opens at the Kennedy Center. Does the road design for the show differ from what’s on Broadway?

The challenge with Hamilton was, we really liked what we did. The show was obviously incredibly successful and there’s not a lot of physical scenery. There’s a lot of square footage. But the idea of the show is that it really is a complete environment. So our challenge in bringing it to D.C. and around the world is that we have really tried to deliver what is exactly the Broadway show.

The abstract metaphor of the design aesthete is that we are telling the story of the people who built the scaffolding from which the foundation of our country is built. So we have a wooden scaffolding wrapped around these double brick walls, as if to see the innovation and the aspirational quality of their building going up.

The challenge is this is a set that stands for permanence and foundation and sturdiness. And the irony is for a touring show, how do you take something that has to load in eight hours, snap together and come off a truck—how do you engineer it so when it snaps together, it looks and feels permanent, and basically delivers the same physical production on Broadway? That was my big challenge.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/55/09/55092985-5a75-4382-9d92-3bdd3c0fe91f/david_korins.jpg)

Did you keep that in mind when you crafted your original design?

I try not to have it in mind when I make the original design because I think it’s important to really crack the code of what the show wants to be. You never really know if a show is going to go on tour or anything like that, so you try to design it for the Broadway production.

Most of the time when a Broadway show tours, you try and boil down the essence of what the set design and the physical production looks like. But inevitably you make pretty big compromises and cuts and no one ever knows because very few people see the show both on Broadway and on the road.

There will be people who will have seen it on Broadway and will see it on tour. What will they notice?

They will notice no different. If they notice a different they’ll get a prize. Other than the overall physical perimeters of a tour, meaning, the overall portal and the size of the Richard Rodgers Theatre is different, obviously, than for the portal on the road, my goal was—and I believe we were very successful at achieving it—was to make it so that if you saw the show on Broadway, you would see no difference.

Between acts one and two, the brick wall in the back will grow eight feet, as it does on Broadway?

I believe the production that you will see will have that feature, yes.

But the production won’t exactly be loaded in and out quickly—it will be in Washington, D.C. for three months.

Yes, but we still drop the trucks off on a Sunday and we open on a Tuesday. Although D.C. is one of our longer stints on the road, we still have to be ready and prepared to have an audience on that Tuesday, I believe.

How did this design come together for you originally?

The process of Hamilton was not that much different than the process of designing any other show. I normally try to keep my cards a little bit close to my vest when I’m interviewing for a job, because we trade in the currency of ideas, and I think sometimes directors and producers are bringing [designers] in to hear their ideas and shop them against each other.

This time, with Hamilton, I really loved it. No one had any idea [the show] would become the juggernaut hit that it did. I really loved it. Lin was a friend, [director] Tommy [Kail] is a friend; [choreographer] Andy [Blankenbuehler] and [music director] Alex [Lacamoire] were friends and colleagues. I just laid it all out there.

What was the process?

I did a lot of research. I did more research, and more sketching and more thinking about the show, and I was very candid about the show up front, because I loved the material. I really loved the material.

Yeah, it starts with a whole bunch of research—and the nice thing about Hamilton of that time period, there’s plenty of research. Obviously, some of the locations still exist, whether it’s The Grange [Hamilton’s home in New York City], or Valley Forge, or any of these places where you can go and see some of these real spots. There are also certainly paintings and etchings and drawings. So, you can take a pretty deep dive, and design the show realistically, although you would never be able to execute that because it takes place over 30 years in a huge sweeping story so we had to boil it down to one tapestry of early American architecture that could house, in a metaphorical way, the entire story.

Did that mean compromising or necessarily leaving some elements out because you had to use a central setting?

I certainly would not call them compromises, because I feel like part of the job of a set designer is to create an environment that is evocative and thought-provoking and houses the show and props it up in a way so that you can actually see and hear the show.

My goal was not to steal focus in any way. In fact, one of the only things that I worried about early on, because a show like that had never really been seen or heard, was: is everyone in the audience regardless of age, going to be able to hear and understand every single word at this cadence and this pace—and there’s more words in this show than perhaps any show ever written.

Will they be able to hear it? I don’t want to pull focus. I want to try to crystallize every moment for the audience and not layer on too many other things. So to me, it wasn’t about compromise, it was about being a better storyteller with less scenery.

Was the turntable always part of the design?

The turntable for me was always a part of it. Although for the overall show, it was definitely not always a part of it. I had a hunch early on that the show took place on a turntable or that we would be able to use a turntable with great effect. I think I was inspired by the fact that Hamilton was swept off the island of St. Croix by a hurricane. I think I was inspired by the cyclical relationship of Aaron Burr and Hamilton, and the fact they basically had a cat and mouse game their entire careers and their lives. There was also, of course, the political storm and the scandalous storm that Hamilton creates for himself. Then of course, the turntable is really a great storytelling device to move things and people around on stage in a cinematic way.

I pitched the idea of a turntable in the very first meeting to Tommy Kail, the director, and he had never worked on a turntable before, and he said: “Yeah, I’m not so sure.” Then we actually went eight months into the design process, designing all the rest of the bits and pieces of the show and it wasn’t until very late in the rehearsal process, before we opened at the Public Theater, that we added the turntables to the show.

What revived the turntable idea?

Actually, my associate Rod Lemmond, said to me, “Remember that idea you had?” We were storyboarding the show—me and the director and the choreographer—and we were having a hard time figuring out how all the desks and the pieces of furniture and the chairs and everything came on stage and Rod said, “remember that turntable idea?”

And Andy and Tommy said, “If you can come up with ten places in the show where we would use the turntable, we’d think about it.” And I sat down and I drew ten examples of how I thought it could be used, and they said okay, let’s do it.

Apparently three years later, you’re still working on Hamilton, since your announcement early this month that you’ll open a big Hamilton exhibition in Chicago late this year.

That’s correct. I’m not only still working it, but I’m involved with all sorts of different tendrils of the Hamilton enterprise, not the least of which is “Hamilton: The Exhibition.” What I will say about that is that I’m not just working as the set designer on that, I’m also creative director on it, so I’m really kind of sculpting and creating the entire holistic journey for the visitors.

Within that role, I must say, the level of rigor and research to create the Hamilton exhibition has been so much more than the level of research and rigor with which I used to design the scenery—and that’s not to say that I didn’t do a ton of research on the design of the set, because I did. And I gotta tell you, we got so granular with the design of the set, I didn’t really imagine there could be more for the design of the physical location.

But with “Hamilton: The Exhibition,” I have learned more about American history and more about the life and times of Alexander Hamilton, the people he bumped into in the world, and how he bumped into history, than I ever thought I would. It’s exhaustive the amount of research we’ve done for that project.

Do you think visitors will feel that as well?

That is a 27,000-square-foot, fully immersive, 360-degree experience that takes you literally from St. Croix all the way to the dueling grounds and beyond, to his legacy. So, people will be fully immersed in it.

Whereas our moment in the hurricane in the show takes place on our wood-beamed, scaffolding and brick under a beautiful light—and that moment is beautiful that Andy and Tommy and Lin have created with the help of Howell Binkley, our lighting designer, and Nevin Steinberg, our sound designer, and Paul Tazewell, our costume designer, it’s gorgeous. But the Hamilton exhibition literally takes the Hamilton trading post in St. Croix, literally blows it up into a kinetic, moving, swirling, Alexander Calder-esque mobile, floating slowly, as you walk up a Guggenheim style spiraling ramp through a frozen hurricane-submerged moment, with lights, and sound, and video projections and the writing of the man’s words. So it’s a totally different immersive experience.

It sounds very theatrical, as well.

That’s one of the things that I think about in my life. And Tommy Kail, the director of our show, gave me this little tidbit—I collaborate with him on a lot of different things. He said to me: “We should only do what only we can do. “

I’ve had the privilege of designing museums, galleries and exhibitions, and hospitality and restaurants, and things like that, a lot. But when I think of the Hamilton exhibition, you will see that we are doing what only we can do.

We’re taking an incredible amount of rigor—I’m not an American historian but we worked with Annette Gordon-Reed and Joanne Freeman, who are two of the foremost Hamiltonian and Jeffersonian historians in our country. They have taken care of the history for us, and we have taken care of the theatricality and the experiential. And I think it really is a perfect complement and collaboration between a lot of expert people.

Is it designed to move to other places eventually, or is it just a one-time thing for Chicago?

It is absolutely designed to be in other cities. It’s in a 27,000-square-foot moveable tent.

What other things are you working on? You’re working on the set for the upcoming musical of Beetlejuice, right?

I am working on Beetlejuice, which will also start in the lovely city of Washington, D.C. [this fall]. I have a 20-person design company, so we are currently in the middle of a lot of different projects. We’re doing a very, very high-level collaboration with the Chatsworth House in England and Sotheby’s, we’re taking an immersive experience to Asia, we’re working on “Hamilton: the Exhibition” and Beetlejuice—we’re doing many many, things.

We’re the creative directors of a very large announcement that’s going to happen in Detroit next month, which will bring a whole bunch of innovation to the city of Detroit. And lots of different, cool things.

Even as your firm grows, what remains your favorite thing to do?

I started as a theatrical set designer. And I love that. As a designer on the stage you get to conjure an entire world. It starts with nothing, a blank stage, and you get to fill the entire box up with a full world. What’s so interesting that’s happened over the last 15 years, and especially the last five years, is that the entire world has become theater.

You can’t watch the Super Bowl or the Olympics or any kind of literary endeavor or television show that doesn’t want to create some kind of experience. So, what we’ve started to do is basically take ‘theatre,’ which takes place in the traditional sense, in a fourth wall setting, like the way that you see Hamilton.

I’m really excited about expanding the definition of theater, and expanding brands and intellectual properties into three dimensions and really sculpting an entire consumer journey. And that has been really interesting. I guess the theater kid in me still very much rules the roost. It’s just about delivering the theater of different stories.

“Designing the World of Hamilton,” a Smithsonian Associates program with set designer David Korins in conversation with The Washington Post theatre critic Peter Marks, is Thursday, May 31 at 6:45 p.m. at the National Zoo Theatre in Washington, D.C. The event is sold out, but call 202-633-3030 to get on the waiting list.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)