Help Transcribe Field Notes Penned by S. Ann Dunham, a Pioneering Anthropologist and Barack Obama’s Mother

Newly digitized, Dunham’s papers reflect her work as a scholar and as a scientist and as a woman doing anthropology in her own right

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7f/e3/7fe337f1-78bd-4a99-8942-2d11090a4f4c/dunham_fig_01_lambok.jpg)

Stanley Ann Dunham’s decades-long perseverance led to her success as a pioneering anthropologist. Despite facing societal pressures and stigmas around interracial, intercultural marriages, conducting fieldwork while raising children—including the future 44th President of the United States Barack Obama—and being a female academic in the traditionally male-dominated cultural anthropological field, Dunham dedicated her career to elevating the role of women in societies throughout the developing world. Her contributions to the understanding of localized and diverse economic systems have impacted not only fellow cultural anthropologists, but major nonprofit development and global aid projects.

The records of Dunham’s immersive study of craftsmanship, weaving, and the role of women in cottage industries in Indonesia, Pakistan and beyond, as well as chronicles from work with non-governmental organizations (NGOs) are now publicly accessible in the form of her transcribed field notes now held in collections of the National Anthropological Archives (NAA) housed at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. Dunham’s notebooks were recently digitized as part of a Smithsonian Women’s Committee grant awarded to the Transcription Center and six other Smithsonian Institution projects to highlight women in archival collections.

“Dr. Dunham's work on artisans in rural villages in Indonesia helped to shed new light on the dynamics of village economies and the realities of traditional crafting. Through her jobs at USAID, Ford Foundation and the Asian Development Bank she was instrumental in promoting and establishing microfinance in Pakistan and India, thereby assisting rural villagers. Her archival materials provide invaluable data for the communities she worked with and future researchers,” says Joshua Bell, the Smithsonian’s NAA director.

Dunham began her fieldwork in Jakarta, Indonesia, in 1968, and from 1976 to 1984 learned about metalsmithing and textile crafts while working for the Ford Foundation. She developed a microfinance model to help make these and other artisan industries sustainable economies that could especially support women and children. Today, microloans Dunham established through World Bank funding are part of portfolio of financial programs used by the Indonesian government to support underserved populations.

According to social ecologist Michael R. Dove, Dunham’s efforts “challeng[ed] popular perceptions regarding economically and politically marginalized groups; she showed that the people at society’s edges were not as different from the rest of us as is often supposed,” and were “critical of the pernicious notion that the roots of poverty lie with the poor themselves and that cultural differences are responsible for the gap between less-developed countries and the industrialized West.”

Ethnographic and cultural anthropological research has been plagued by its long, problematic colonial history. Dunham’s immersive methods highlight the importance of establishing a social contract in this field, especially, in order to accurately and ethically represent community perspectives through a collaborative effort.

“I think if you're not an anthropologist, even just her methodology of spending a really long time with people and living with people and getting to know everyone and working closely, is something that lends itself to intercultural appreciation and communication and knowledge that we all can be reminded of,” says Diana Marsh, a postdoctoral fellow at the NAA, who contributed to the digitization project. “Any field note, any set of field notes gives you a window into what those relationships look like and I think that will be really valuable.”

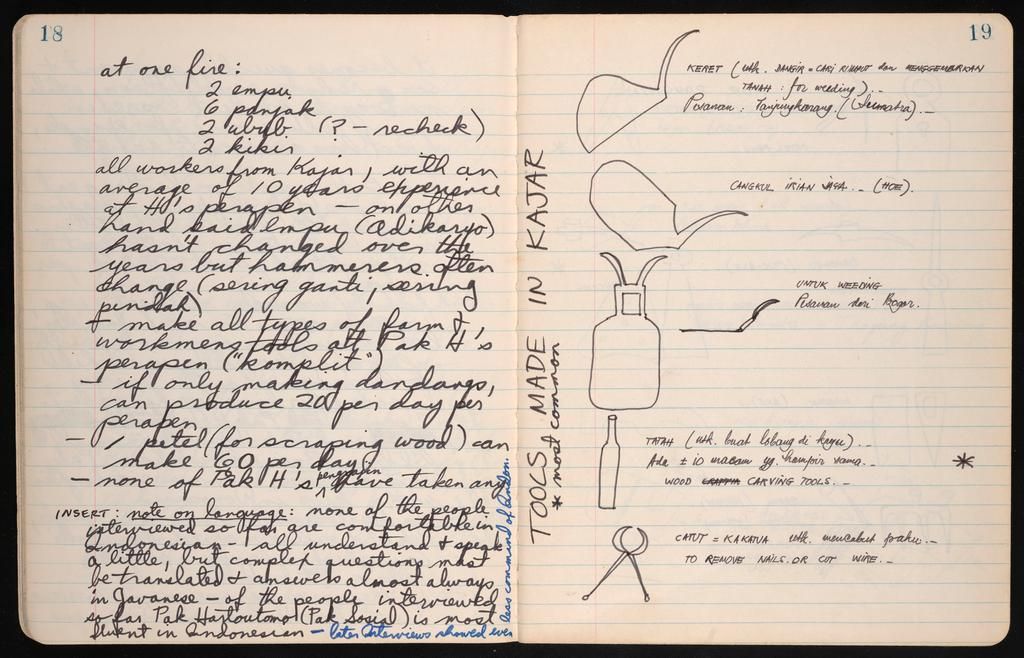

Dunham used documentary photography to create a visual record of traditional craft and everyday life among Indonesia’s diverse cultures. Her field notes include descriptions and sketches of the tools used in the crafting of intricate textiles, metalworks and other valuable commodities. Significantly, descriptions in the notes capture the complexity and nuance of traditional crafts to detail how these industries function and how the economies they're part of operate to sustain livelihoods.

“Dunham is somebody who is known mostly through her relationship to a man. I think the field notes will illuminate for the public her work as a scholar and as a scientist and as a woman doing anthropology in her own right. And I think a lot of her methods will be really clear through the field notebooks because you can see the kinds of conversations she's having,” says Marsh. “Some of her notes include later work with NGOs so there could be really interesting nuggets in there about other kinds of careers in anthropology besides the traditional scholarly route. And I think it's also really important and underrepresented in the archives,” she adds.

The S. Ann Dunham papers, 1965-2013, were donated to the NAA in 2013 by Dunham’s daughter, Maya Soetoro-Ng. The donation included field notebooks, correspondence, reports, research proposals, case studies, surveys, lectures, photographs, research files and floppy disks document of Dunham’s dissertation research on blacksmithing, and her professional work as a consultant for organizations like the Ford Foundation and Bank Raykat Indonesia (BRI).

Beginning today, the public can contribute to the NAA’s effort to transcribe Dunham’s field notes.

“The S. Ann Dunham Papers held in the NAA are extensive, but only her field notebooks have been digitized so far. All of these have been imported into the Transcription Center and will be available for transcription. There are around 30 notebooks—so it’s a pretty large amount of materials, plenty to transcribe,” says Smithsonian Transcription Center coordinator Caitlin Haynes.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sexton_Remy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sexton_Remy.jpg)