Here’s What It Takes To Win the Smithsonian’s Boochever Portrait Competition

Curator Dorothy Moss gives a hint at what the jurors might be thinking in this high-stakes competition

:focal(704x459:705x460)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8a/9d/8a9d93c8-23d5-48c4-afc1-51ce08a413b7/lenz-davidweb.jpg)

Portraiture is experiencing a renewed moment of relevance in the contemporary art world. This is evident at the major art fairs and in the rise of retrospectives of artists who have pushed the genre of portraiture forward, including a host of retrospectives this year on Carrie Mae Weems at the Guggenheim, Marisol at the Museo del Barrio and Larry Sultan at LACMA. Thus it is not surprising that the definition of portraiture is continually evolving and expanding.

Every three years the National Portrait Gallery invites artists, 18 and older, living and working in the United States, and who had a direct encounter with their subject to submit works to the highly prestigious Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition. The participants range from students and emerging artists, to the self-taught and to well-established, internationally recognized artists at the height of their careers.

The stakes are high and the honor is significant for an artist at any stage of his or her career. The $25,000 first prize winner is commissioned to create a portrait for the museum’s permanent collections of a living person who has made a significant impact on the history and culture of the United States. A jury of contemporary art curators, critics and scholars convene in Washington, D.C. for two lively gatherings, charged with heated exchanges and vigorous debate. In an understatement, Thelma Golden of Harlem’s Studio Museum, a 2006 juror, called the process “an extended conversation about art among a group of individuals with different backgrounds, specialties, ideas, and tastes. There is always a certain amount of give-and-take in the jury process.”

With only a few days left for artists to enter the competition for the 2016 winner, possibility abounds. The slate is clean and it will be up to the jurors Dawoud Bey, Helen Molesworth, Jerry Saltz, and John Valadez to select a winning portrait that, in the words of Dawoud Bey, “creates an experience for the viewer.” In order to achieve this intangible quality, 2013 juror Hung Liu urges artists to create something that he or she “believes in.”

Highly conceptual work and even performance art amplifies the variety of fresh and often surprising approaches that today’s artists are taking towards a once inherently conservative genre. In fact, the selection process is revelatory, providing moments for the jurors and the museum’s curators to further study the evolving nuances of identity through portraiture in its multiple forms as it changes in the intervening three years between each competition. The submissions always shed new light on our historical portrait collections and suggest a working roadmap for the future, stimulating ideas for exhibitions and commissions.

The previous three first-prize-winning portraitists—David Lenz of Shorewood, Wisconsin, Dave Woody of Fort Collins, Colorado and Bo Gehring of Beacon, New York)—surfaced among a sea of thousands of entries and after prodigious debate among the jurors. What do these artists’ choices in creating their portraits—a painting, a photograph and a video portrait—say about how portraiture works in a cultural moment? Portraiture stands at an iconic threshold when photographic portrayals of celebrities and pop icons are discussed in the mass media in terms of their power to “break the internet”? What makes a portrait stand out when everyone is making selfies? As 2016 juror New York Magazine critic Jerry Saltz writes:

Selfies have changed aspects of social interaction, body language, self-awareness,

privacy, and humor, altering temporality, irony, and public behavior. It’s become a

new visual genre—a type of self-portraiture formally distinct from all others in history.

Selfies have their own structural autonomy. This is a very big deal for art.

The rise of the selfie is an especially big deal when considering how artists push away from it, a theme that unifies the past three winners. Each challenges the nature of subjectivity to move ultimately beyond the self to a more universal view of the subject, especially in relation to the artist and to the viewer and within the context of the history of portraiture.

In 2006, David Lenz oil on linen portrait of his son, entitled Sam and the Perfect World depicts a child with Down Syndrome. For Lenz, this was the “most personal painting” he’d ever done. “It touches on all the various issues that challenge our family,” he said. Without a hint of idealization or sentimentality, and without crossing the threshold into dramatizing the complex father-son relationship captured here, Sam is shown posed in front of a barbed wire fence. A bucolic country landscape with a pulsing sun reverberating in the pale blue sky proves the backdrop for a young boy wearing glasses and leaning toward the viewer with his brow slightly furrowed and his arms behind his back. Is he hiding something? Or trying to tell us something? There is something inscrutable and endearing about his expression that makes us want to spend time with him. In his red T-shirt and Oshkosh overalls he is in some ways a classic little boy. And yet he is not. As Lenz says, “Sam is the opposite of the idealized ‘perfect’ countryside. Nevertheless, I think he has something very important to say.” Remniscent of Charles Willson Peale’s The Artist in His Museum (1822), Lenz has crafted a masterful composition with extraordinary technical skill.

Lenz received the museum’s commission to paint a portrait of Eunice Kennedy Shriver. Like Lenz’s portrait of Sam, Shriver’s portrait has a magic realist quality that comes from the way the artist paints light. Here it flickers across the water and sand after a storm has passed over Cape Cod, the black clouds retreat behind the figures. Paying tribute to her work with Special Olympics, Shriver appears with her companions, all individuals with intellectual disabilities. Their faces share a sense of wonder and compassion in their expressions and poses. Interconnected yet individual they shift between the ordinary and the archetypal.

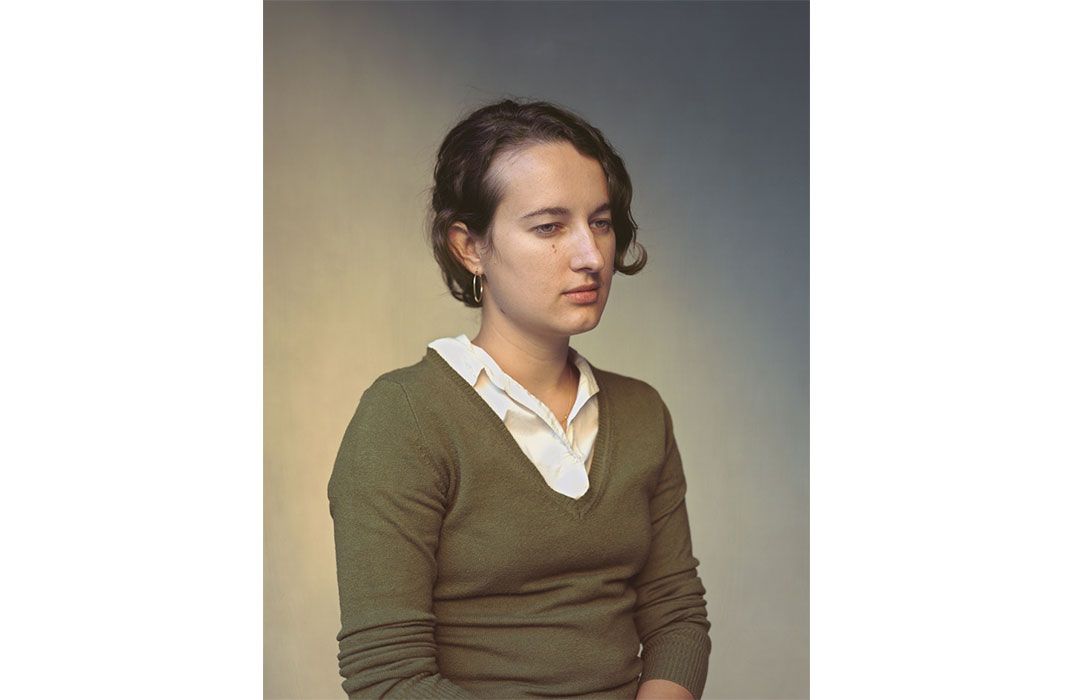

In the 2009 competition, photographer Dave Woody submitted Laura, a photograph of a fellow graduate student at the University of Texas at Austin. The jurors noted that Woody’s portrait is painterly and quiet, infused with a golden glow that he describes as being specific to his studio space in Austin. “I don’t know physics really,” he writes, “but the light quality, or the heat in Texas, something was magical about that space. You’d get these really big colors, kicking off something someone wore. The combination of light, color and ambiguous space deeply affects the emotional experience of those portraits.” Laura’s pose and expression calls to mind the meditative quality of the works of 15th-century Northern Renaissance master Jan Van Eyck, especially his portrait of Giovanni Arnolfini (c. 1400), or the stark, quiet mystery of Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring (1665). That a large-format photographic print carries forward the portrait tradition of such iconic paintings in the history of art without mimicking those portraits or being derivative is the testament to the artists’ eye and working knowledge of his predecessors. The New Yorker’s Peter Schjeldahl, a juror that year, noted: “We judges have awarded first prize to a photograph that grew on us as an instance of the real thing: a picture in which the attitude and spirit of the subject and the skill and sensitivity of the artist become, inextricably, one.” For his commissioned portrait, Woody chose to portray Alice Waters.

Taking the photographic portrait into the realm of motion and sound, the jurors awarded the 2013 award to former engineer and computer programmer Bo Gehring, who draws on the work of early 20th-century German documentary photographer August Sander and 20th-century American fashion and portrait photographer Richard Avedon. To create documents that Gehring sees as “messages to the subject’s grandchildren,” the artist’s growing archive of video portraits of people he knows in and around Beacon, New York, document a time and place with sensitivity and extraordinary technical mastery of process. Gehring entered his portrait of precision woodworker Jessica Wickham. As is typical of his portraits, Wickham is filmed lying down with a camera track above her. As she listens to Arvo Pärt’s "Cantus in Memory of Benjamin Britten," a mesmerizingly exquisite musical piece that she chose, the viewer sees in astounding detail a blood stain on her pink socks, each speck of lint on her gray corduroys, the soil ingrained in her worn lime green jacket, her heartbeat pulsing under her purple turtleneck, the pulse beating in her neck, and eventually her eyes, which shift three times from direct contact with the viewer back to the music as the camera passes over her. Gehring’s hope is to capture his subject’s emotional response to music over time as the video camera is timed to coincide with the musical piece. The intimate resulting portrait reveals what the eye could never see in motion with such precision and specificity and the viewer stands transfixed, fully immersed in the moment with the subject and the artist. This, the jurors said, was in itself a remarkable feat for an artwork to achieve in this fast paced age of multitasking and distraction. After Gehring created his portrait of jazz musician Esperanza Spalding, the subject of his commissioned portrait for the NPG, Spalding stood up, took a deep breath, and said, “thank you for reminding me to slow down.”

The call for entries for the 2016 Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition closes on November 30, 2014.

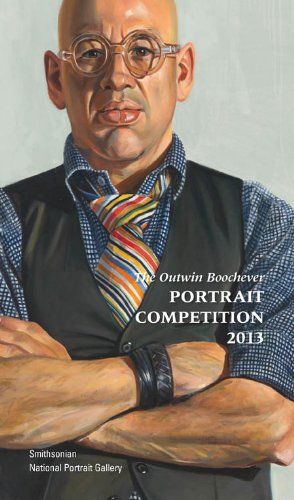

Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition 2013

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/dorothy_moss.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4d/da/4dda1537-21b8-46a7-ad61-fcfa1c054efd/alice-waters-highres-web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8a/9d/8a9d93c8-23d5-48c4-afc1-51ce08a413b7/lenz-davidweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/dorothy_moss.jpg)