Sam Calagione’s boil kettle—discolored from heavy use and topped with a repurposed kitchen pot lid, looking a bit like a mismatched hat—didn’t arrive alone last week to the storage shelves at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

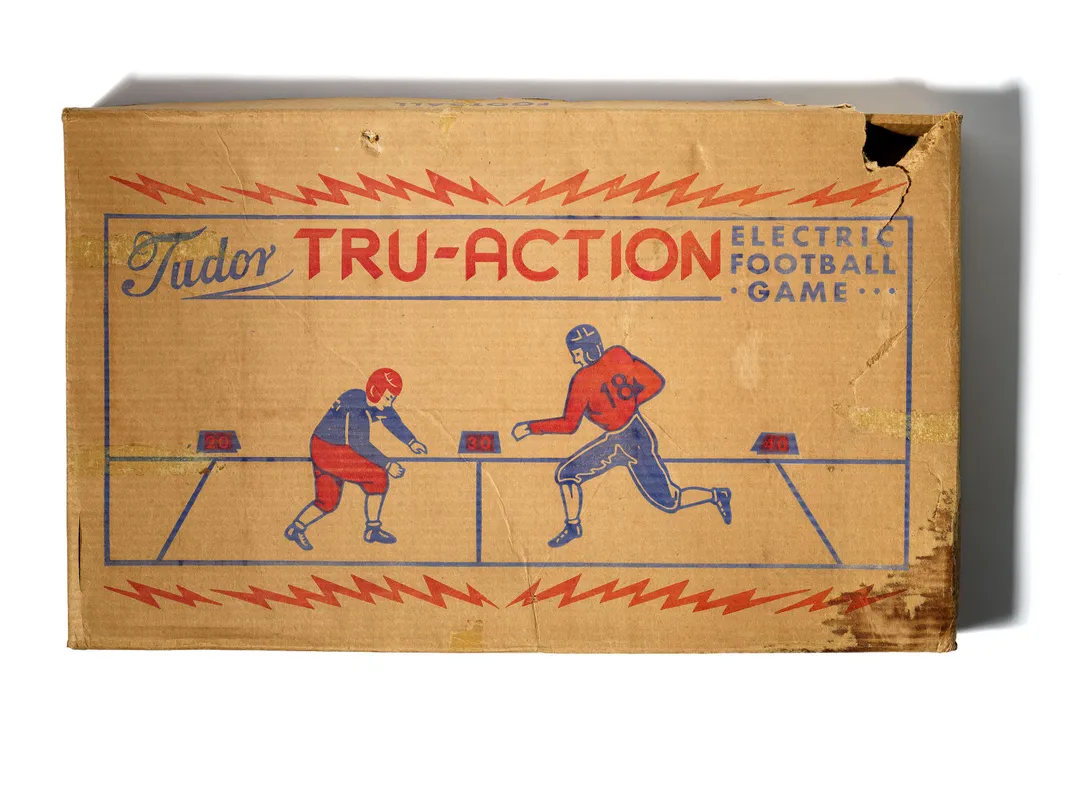

Calagione, the founder of Dogfish Head Craft Brewery, formerly Dogfish Head Brewings & Eats in Rehoboth Beach, Delaware, also donated a vintage vibrating electric football game—yes, you read that correctly.

The innovative Calagione purchased the novelty toy at a nearby thrift store, added a few self-fabricated parts, angled it over his kettle, and used the vibrations to shake hops gently and continuously into his brew, inventing the technique of continual hopping. “My Dogfish Head co-workers and I are excited to have our brewery’s original boil kettle and continual-hopping invention now within the Smithsonian’s permanent collection. This American institution is all about shaping the future by preserving our country’s heritage,” says Calagione.

The trick that packs a powerful—and, to many, tasty—bitterness became familiar to craft beer “hop heads” in the brewery’s 60 Minute IPA, named for its sixty minutes of continual hopping. The ends were quirky; the means of achieving the ends even more so.

With its arrival into the Smithsonian collections, Calagione’s longtime brewing equipment began a new life, beyond the brewery. Dogfish Head’s founding stainless steel boil kettle and vibrating football game joined the growing archive of homebrewing and craft beer history that is being built by the museum’s American Brewing History Initiative.

Researching, collecting, preserving and sharing this history has been my charge as curator of the Initiative. Since January 2017, my search for the histories of homebrewing and craft beer has led me to destinations as far away as 49th State Brewing Company in Anchorage, Alaska, and as close to home as Denizens Brewing Company in Silver Spring, Maryland. There have been more than a few destinations in between, from lagering caves in Cincinnati, Ohio, to a brewer’s off-the-grid cabin in Lincoln, Arkansas, to the breezy shores of Lake Mendota in Madison, Wisconsin.

The Initiative is the first national-scale, scholarly research and collecting project to gather and preserve the artifacts, documents, and voices associated with the beer industry’s recent growth—a phenomenon known as the craft beer revolution. Supported by a gift from the Brewers Association, the museum is constructing this archive for the benefit of scholars, brewers and millions of Americans.

Dogfish Head’s story is exemplary and at the same time one of many. In 1995, when Calagione first opened his brewpub, space was tight and so was the budget. He could afford to buy only a small set of brewing equipment: a 12-gallon system designed for homebrewers, not professionals.

But the beer he made was good. Customers kept coming back for more, bringing their friends. Now he had to brew multiple batches a day, one after the other, each taking four to six hours on burners (followed by cooling, fermenting, and bottling), five days a week. The recipes were starting to feel a bit rote.

The brewpub’s kitchen was full of ingredients, colors and aromas, but most of them were linked to the dishes headed out to diners rather than the sugary wort boiling in the kettle. Nevertheless, Calagione had already imagined the possibilities of pulling from one world into the other. His business plan had set the goal for Dogfish to be the first commercial brewery to make the majority of its recipes with culinary ingredients—cherries, ginger, honey, orange slices, coriander and more—in addition to beer’s standard components of barley, water, hops and yeast.

With these ingredients—the first of many—that Calagione introduced into the boil kettle of his diminutive brewery (a microbrewery, literally) a new approach to brewing American beer began.

Statistics show that most producers and consumers of beer in the U.S. today are white men. But brewing was first the domestic labor of women and enslaved people. As the American economy evolved, beer became the product of immigrant European professional brewers and the output of sophisticated factory breweries.

When happy hour rolls around, most Americans reach for a beer; it is the most consumed alcoholic beverage in the country. In 2017, American drinkers spent more than $119 billion on beer, nearly two times what they spent on wine. According to federal government statistics, more than 6,000 breweries are now in operation, with a staggering 10,000-plus holding a Brewer’s Notice—a measure of potential brewery growth to come.

But the American beer industry hasn’t always looked like this. Homebrewing and microbrewing were grassroots responses to a post-Prohibition brewing industry that had reached peak consolidation in the late 1970s. Very big breweries were making virtually a single style of beer: light-bodied lagers, often brewed with adjunct grains like rice or corn.

Inspired by beers encountered during educational travel or military service abroad in the 1950s and 1960s, some American homebrewers began to brew an adventurous range of beers on a small scale, using only traditional ingredients.

An even smaller number tried to go pro. An initial handful of microbreweries opened their doors in the mid-1970s, mostly in California and the west. At first, this effort was slow-going. Brewers struggled to source capital, ingredients and equipment suited to their modest operations. They had to build distribution networks, marketing strategies and consumer bases from scratch. Many failed.

But many brewers caught several waves at the right moment: the counterculture, the do-it-yourself movement, the consumer movement and even the advent of California cuisine. The federal government legalized homebrewing in 1978. Microbreweries proliferated. And the “craft beer revolution” took hold.

The American Brewing History Initiative is collecting the story of these events and those that followed, gathering artifacts from men and women who changed the American palate and revolutionized an industry.

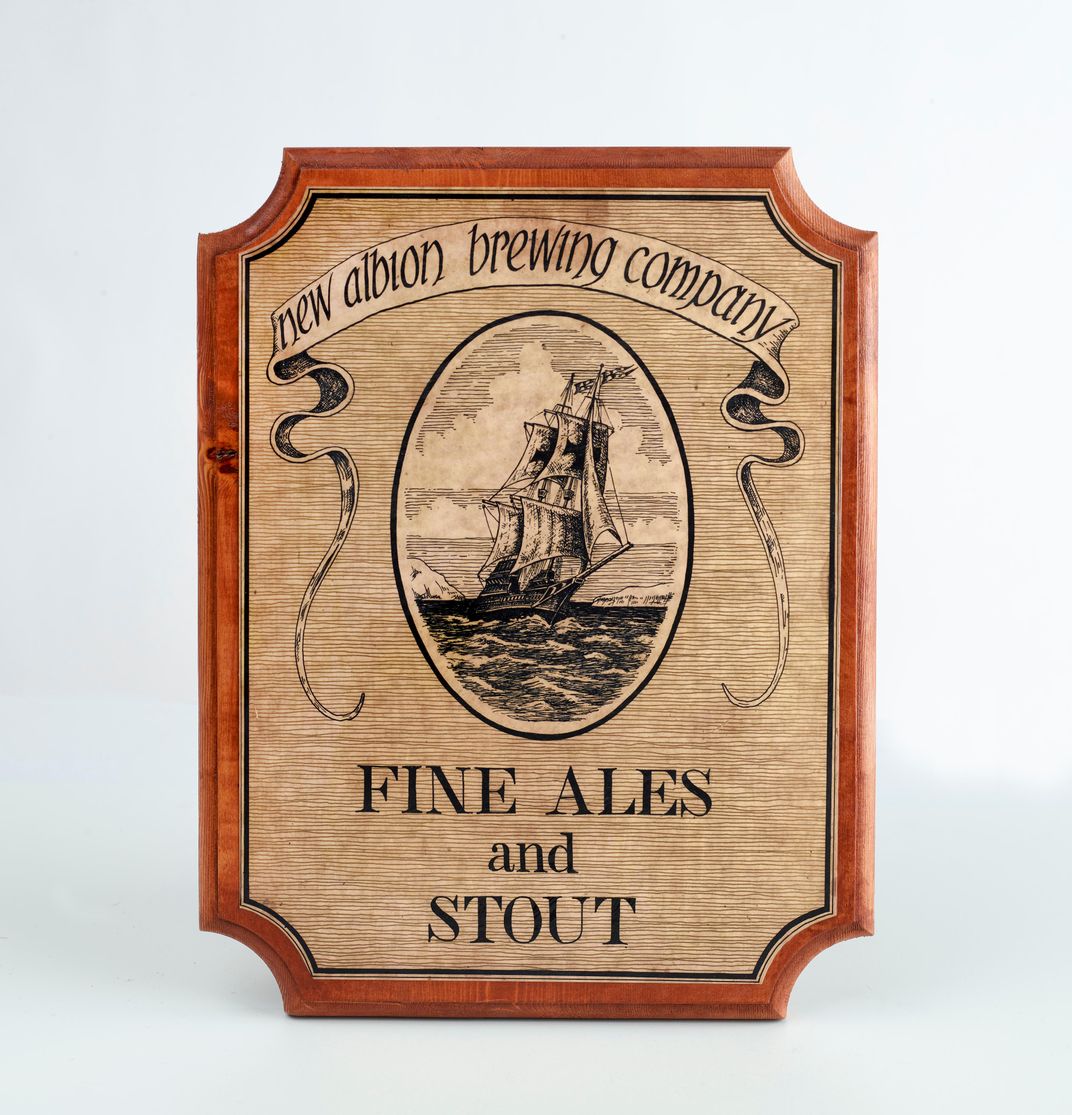

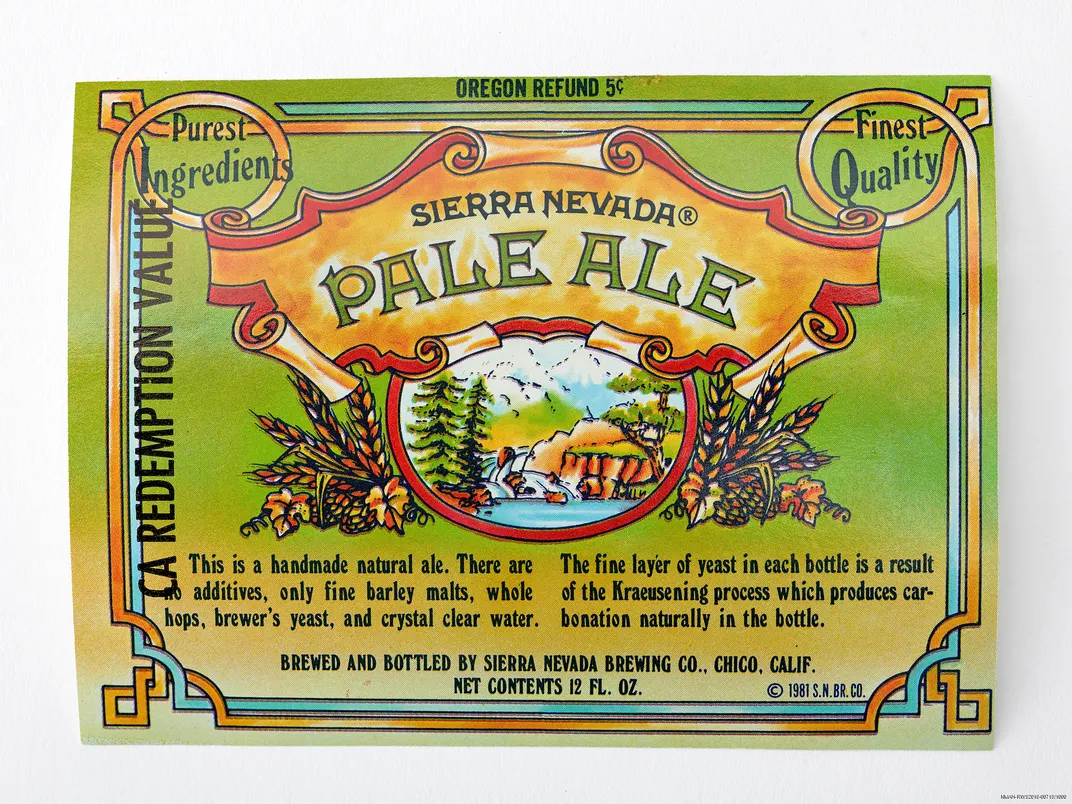

A labeled, though empty, bottle from New Albion Brewing Company in Sonoma, California, the nation’s first from-the-ground-up microbrewery, feels in many ways like the place where this story began. From Sierra Nevada Brewing Company in Chico, California, the Initiative has acquired a first run of labels for beers like its iconic Pale Ale. Buffalo Bill’s Brewery, one of the nation’s first brewpubs, in Hayward, California, has donated a colorful sidewalk sign, bar stool, menu board and tap handles. Other objects reflect growing relationships between fledgling brewers and their customers, such as a guest book recording visits to Boulder Brewing Company (now Boulder Beer Company) in Boulder, Colorado, soon after it opened.

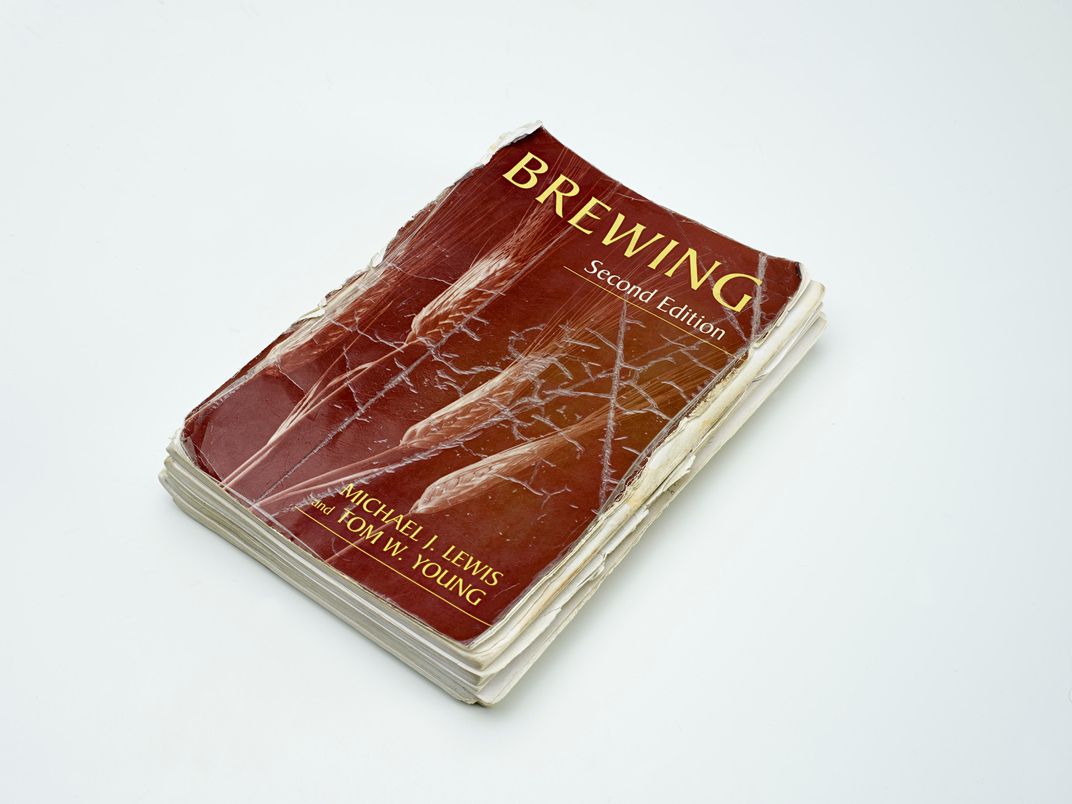

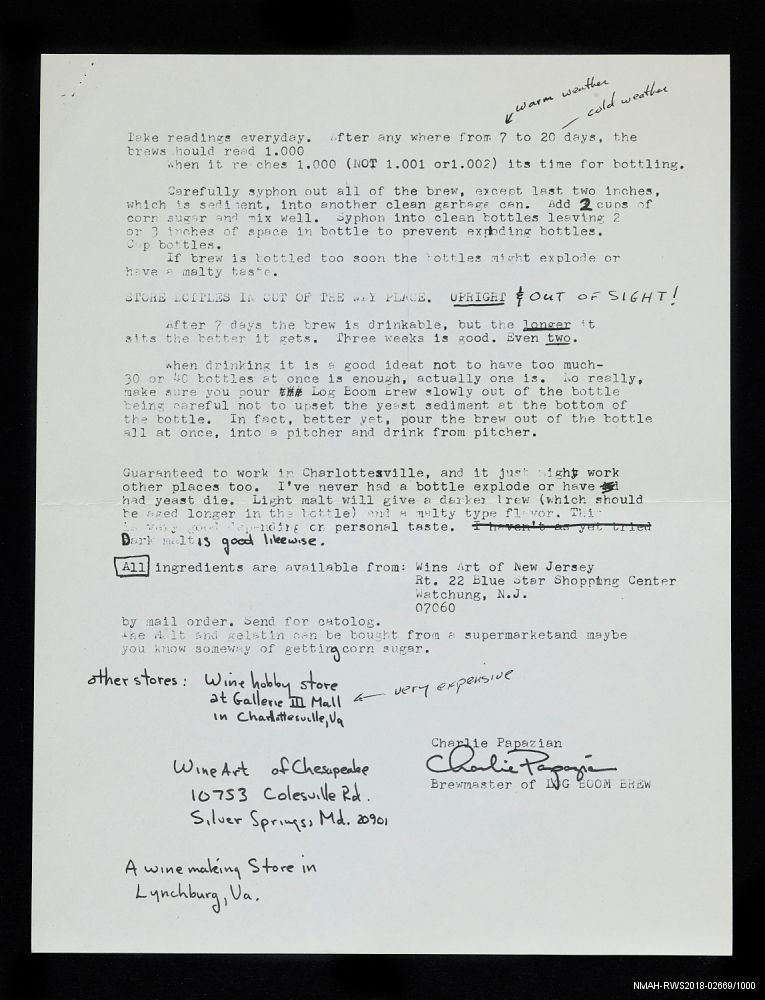

A cherished childhood microscope; a well-worn brewing textbook, its dust jacket patched with tape; a set of white brewer’s coveralls; and a printer’s press sheet of labels from the first modern bottling of Anchor Steam Beer—these objects came from Fritz Maytag, who grew up in Newton, Iowa, where his father managed the Maytag Washing Machine Company. Maytag purchased San Francisco’s struggling Steam Beer Brewing Company—now Anchor Brewing Company—in 1965.

During his oral history, Maytag cited a passion for “alchemy” that he had learned in his childhood basement lab. “I have this magic sense of mixing things together to see what will happen,” he said. Maytag used his childhood microscope to diagnose and fix inconsistencies in the brewery’s beer. He breathed new life into Anchor–and the larger brewing industry–with styles unheard of at the time, like porter and barleywine, making Anchor Brewing Company the nation’s first modern microbrewery.

Michael Lewis, a biochemist born and trained in England and a specialist in the properties of yeast in beer, arrived at the University of California at Davis in 1962 and dedicated the rest of his career to building one of the nation’s preeminent brewing science programs.

As the first professor of brewing science in the United States, Lewis taught homebrewing before it was legal, in the late 1960s. In the mid-1970s, he took his students to visit Sonoma’s tiny New Albion Brewing Company. Lewis donated a selection of his syllabi and teaching notes as well as his co-authored brewing textbook. Its binding is broken and pages marked with marginalia and coffee stains from hours teaching in the lab—traces of a teacher inspiring the creativity of others.

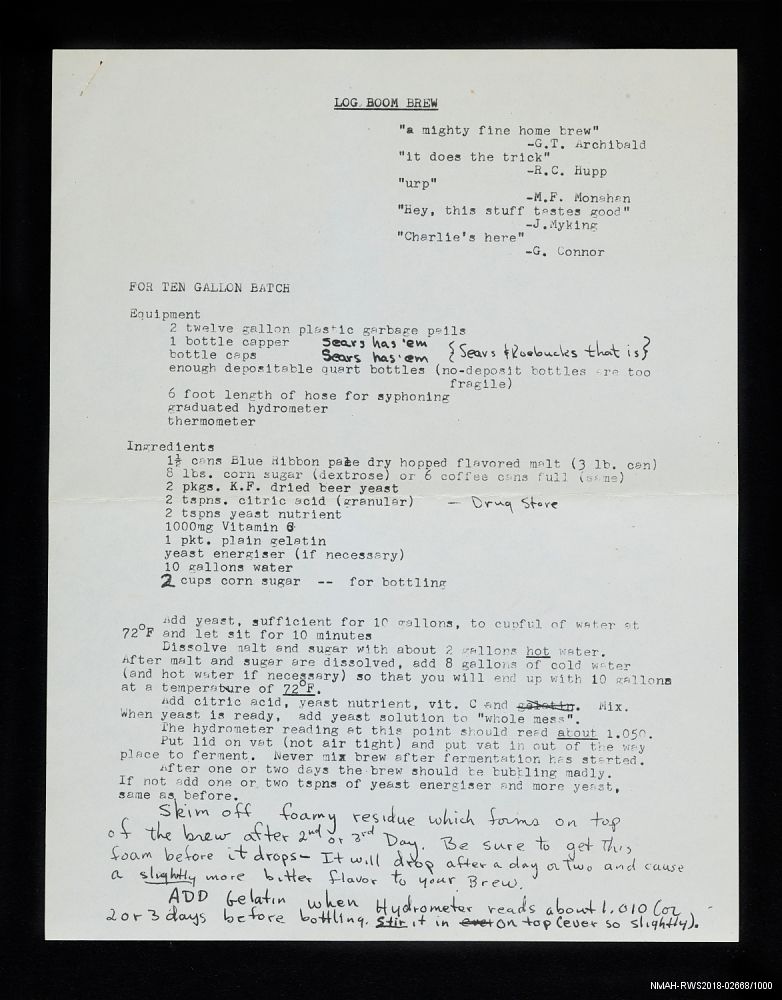

Charlie Papazian was an undergraduate at the University of Virginia in 1970 when he tasted a sip of beer that an acquaintance had homebrewed. Transfixed by the idea that he could make what he realized was “flavorful” beer, he began to brew, too, using ginger ale bottles from the local market to bottle his beer.

Papazian donated two of these bottles to the museum as well as his last original copy of his first homebrew recipe: “Log Boom Brew,” typed while still an undergrad. After college, Papazian moved west, to Boulder, Colorado, where he taught homebrewing classes, authored a popular manual (a self-published first edition now resides in the collections), and founded associations for homebrewers and professional brewers, plus the nation’s largest beer festival.

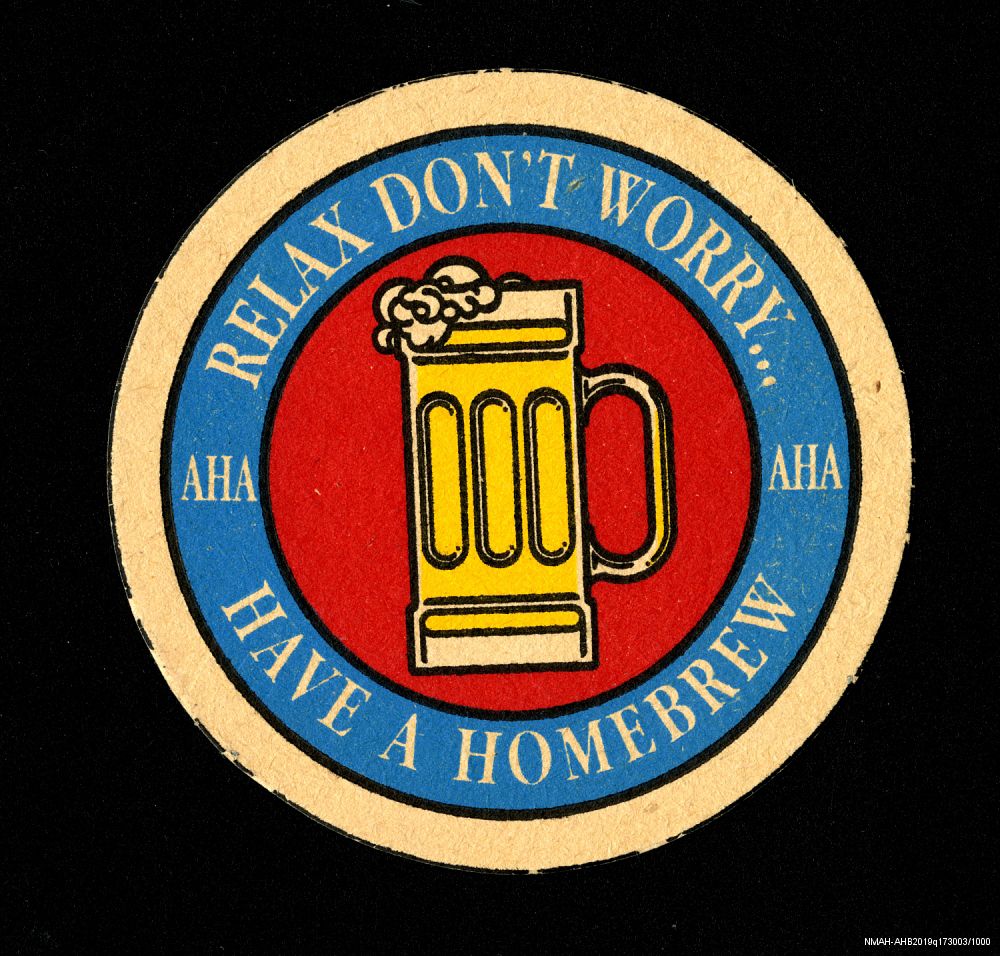

Papazian’s maxim is “Relax. Don’t worry. Have a homebrew.” His humble tools—a wooden kitchen spoon, an aluminum stepladder, and a green plastic garbage pail—now have a new home at the museum.

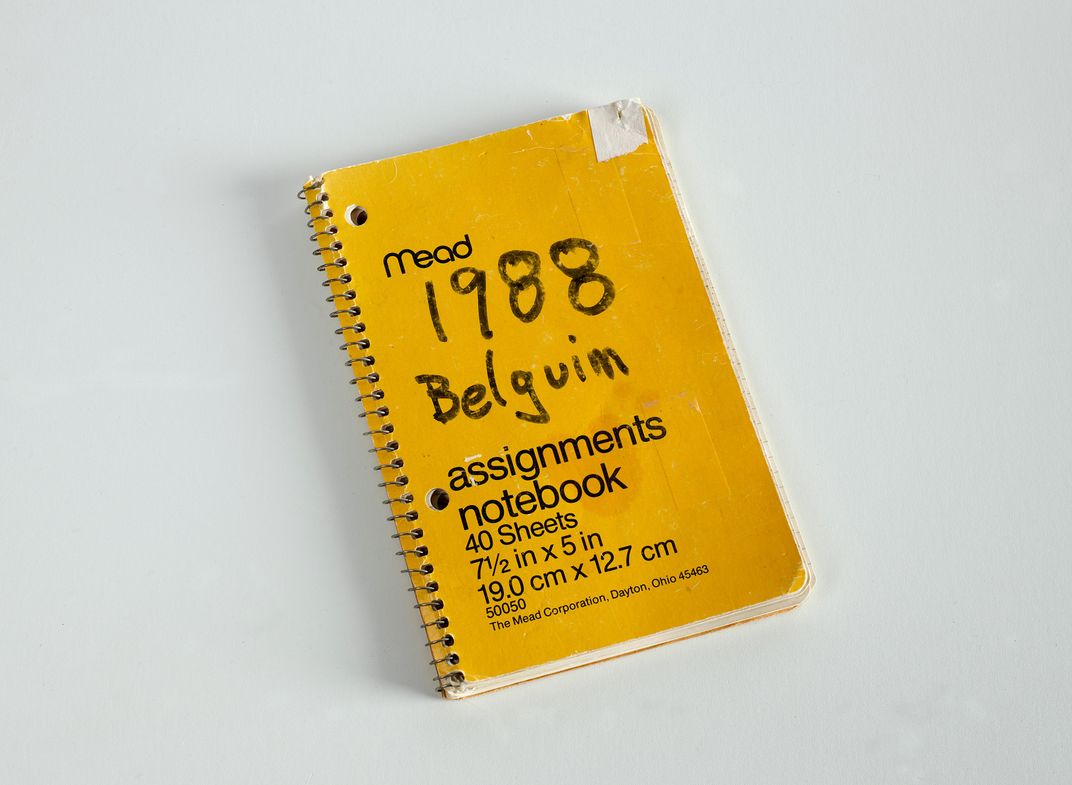

In 1988, Jeff Lebesch carried a small, yellow notebook during a bicycle trip around Belgium. Inside, he recorded tasting notes and observations of the beers and bars he found. Lebesch flew home to Colorado inspired to co-found a Belgian-style brewery, New Belgium Brewing Company, with then-wife Kim Jordan. Lebesch would eventually end his ties to the brewery; Jordan stayed on, becoming CEO and greatly expanding the brewery’s reach. The Initiative has acquired Lebesch’s notebook and a dairy’s milk can used to store yeast during the brewery’s early years.

In addition to these historic artifacts, oral histories recorded with more than 75—and counting—members of the industry contribute in equal measure to this new collection. Professional brewers and homebrewers make American beer what it is today. So, too, do teachers, writers, an artisan maltstress of gluten-free grains, destined for gluten-free beers and a designer of tap handles. Annie Johnson spoke about her experience winning the American Homebrewers Association’s Homebrewer of the Year award in 2013, becoming the first African-American to win that honor. Day Bracey and Ed Bailey, hosts of Drinking Partners Podcast, reflected on their work melding comedy, culture and craft beer for listeners in Pittsburgh and beyond. Liz Garibay talked about enlivening traditional museum work with walking tours of Chicago’s beer history and building a new museum of the city’s brewing past. Oral histories such as these preserve often-winding career paths and capture memories from childhood to the present.

These conversations have taken place while sitting at a bar or in an office; huddled around a barrel amidst fermentation tanks; under the stone arches of a refurbished 1800s malting room; and in conference hotels. Pristine quiet is ideal, but these are oral histories of an industry; some recordings have background noise ranging from taproom bustle to the continuous clink of bottling lines. Interviewees have laughed when reflecting on initial homebrewing escapades and cried remembering mentors who have passed away. These are the details that are harder to preserve and convey in objects or documents, as powerful as those sources are.

From bottles to boil kettles to vibrating football games to oral histories, American brewing history is a series of stories that are economic, social, cultural and gastronomic alike. And as a development of the past 50 years, this history is one that is newly written and still being written.

To a public historian, that fact is an imperative to collect: to gather, preserve and share the material culture and voices of beer’s recent past and present, for the future.

On October 25, the exhibition, FOOD: Transforming the American Table, reopens with the new section “Beer: An American History,” featuring a selection of artifacts from this growing archive. The exhibition includes other new sections on migration and food, dieting history, and Mexican-American vintners.

The museum’s fifth annual Food History Weekend takes place November 7 to 9, 2019. On November 8, craft brewing pioneers Fritz Maytag, Michael Lewis, Charlie Papazian, and Ken Grossman, founder of Sierra Nevada Brewing Company, will speak at the after-hours event “Last Call.” Attendees can sample several of the historic beers created by this star-studded panel of speakers.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2d/bf/2dbfdb0e-f1b8-4767-9819-36fb1b209cc6/sierra_nevada_bigfoot_barleywine_label_xg.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/McCulla_headshot.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/McCulla_headshot.jpg)