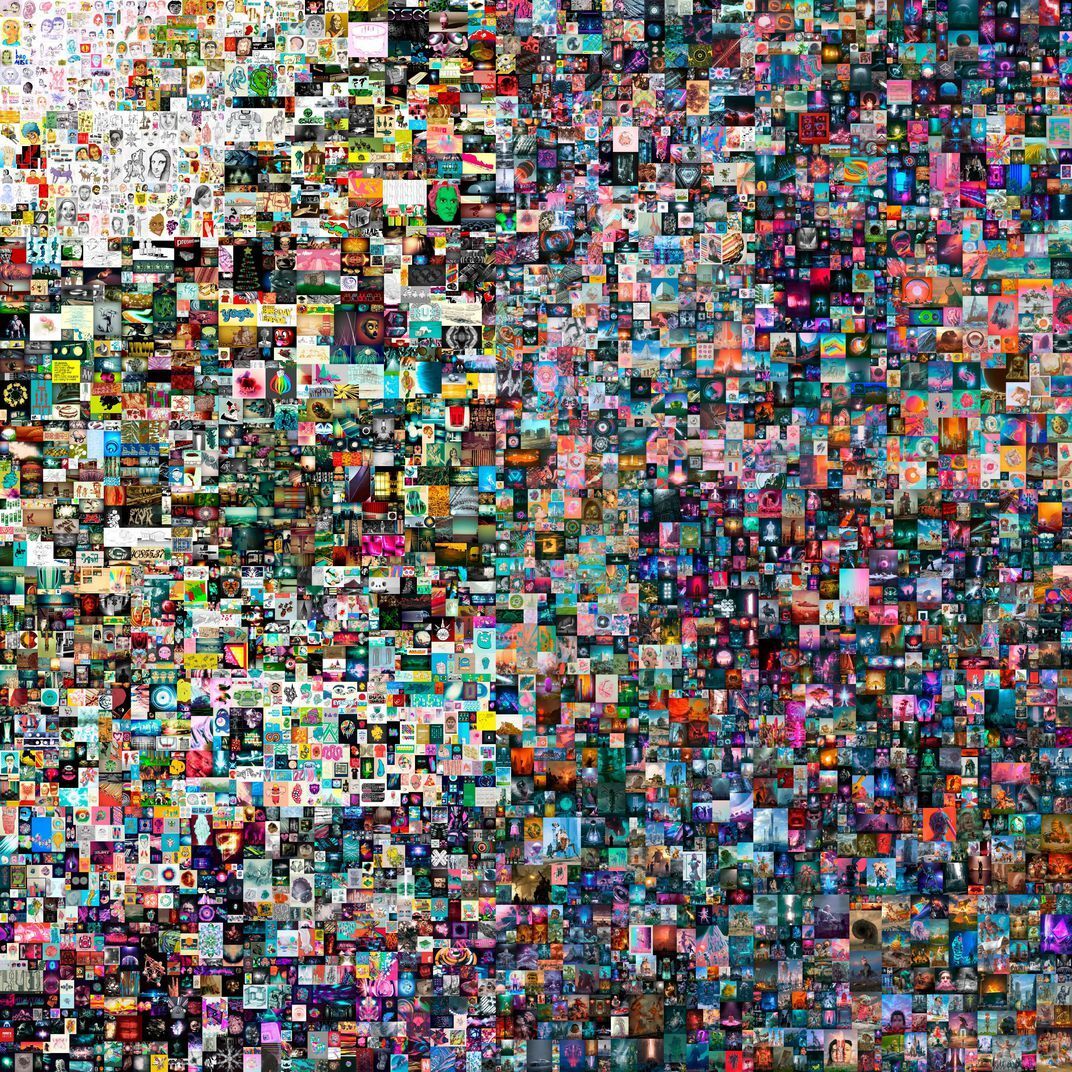

When a graphic designer from Charleston, S.C., who goes by the name of Beeple, sold a digital work for $69.3 million at Christie’s in March, he suddenly vaulted to the top three most valuable living artists in the world.

Beeple’s Everydays: The First 5000 Days was the first NFT—or non-fungible token, as the unique file is called—that Christie’s ever sold. It was a digital mosaic of 5,500 images that Beeple (real name: Mike Winkelmann) had made and posted daily over a 13-year period. One critic who took the time to peruse all the images in the work noted, “None is likely to age well.”

But the true value of what is essentially a JPEG collage is its certificate of authenticity, which the crypto world of blockchain technology transactions can make perfectly transparent. Lots of things have been exchanged as NFTs in recent months, including NBA highlights, traded like baseball cards (a LeBron James reverse dunk went for a quarter million dollars); individual tweets (the first from Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey went for $2.9 million) and well-known viral videos (the British toddler’s complaint “Charlie Bit My Finger” sold for $760,999 on May 23).

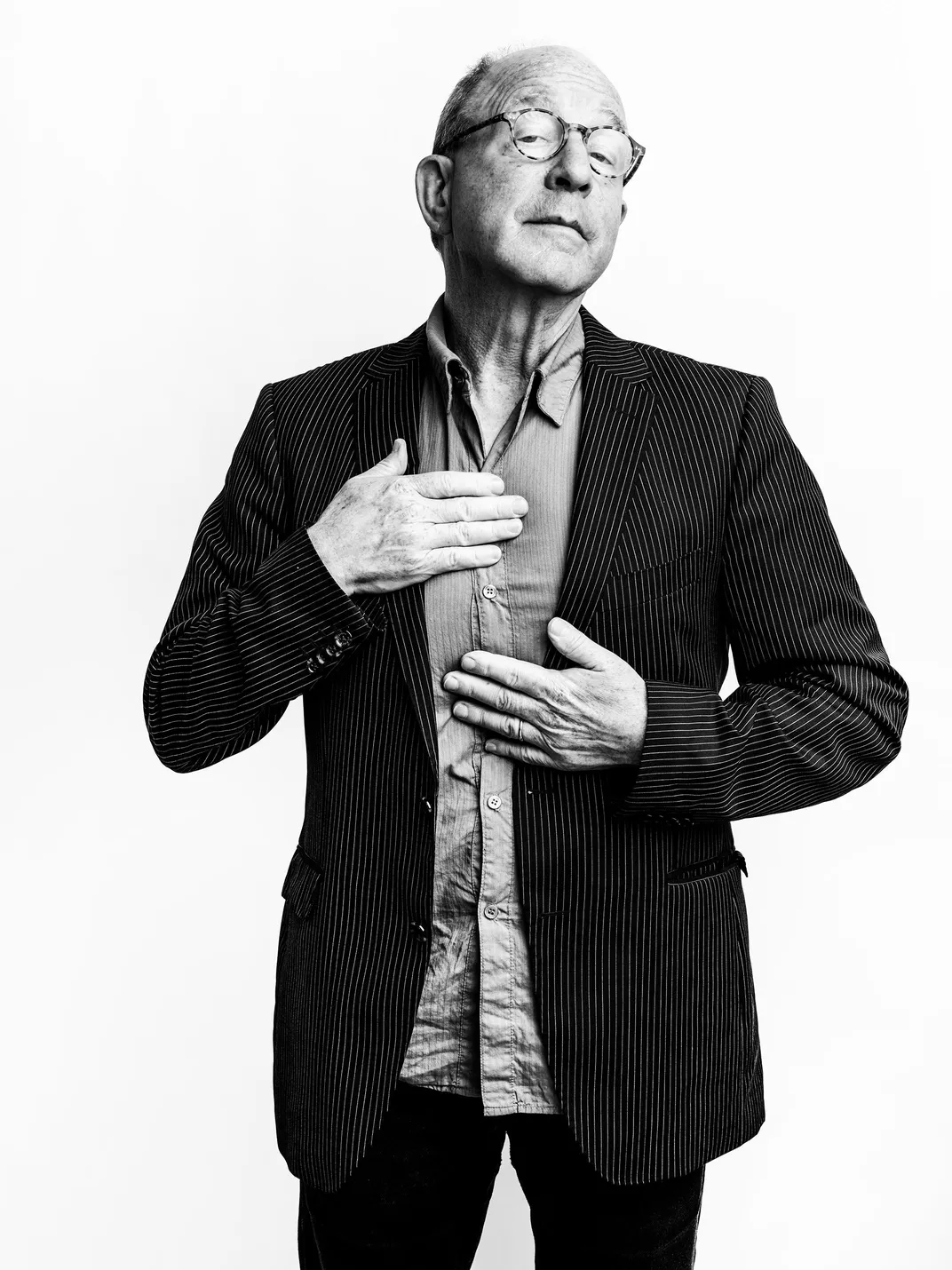

Winkelmann’s work had been rising in value in the crypto world since last fall. But the sky-high auction price shocked the art world, including Jerry Saltz, the Pulitzer Prize-winning critic from New York magazine.

Saltz had been following the rise of the NFT market and decided to razz Beeple’s digital bigseller with his own effort. Teaming with artist and writer Kenny Schachter, the pair devised something to commemorate Saltz’s impending 10,000th post on Instagram (by shrinking them all down to fit in one image).

Like Beeple’s headline-making collage, it resembled so much snow on a television set. Still, it went for $95,000—not bad for a first time artist’s only piece, with all of the proceeds going to charity.

“It was actually a response to the obscene, grotesque, bad Beeple,” Saltz says. “I know nothing about NFTs, cryptocurrency, or poetry, but it doesn’t mean that I can’t immensely want to delve into whatever the form is.”

Schachter wrote what he called their “first market adventure, a headlong dollar dash into the uncharted, choppy waters of NFTism” for Artnet last month. The experience, he said, gave them both a lesson on “the rawness and vulnerability of being market exposed instead of just writing about it.” Winkelmann, for one, chided Saltz by Tweeting, “well well well, look who LOVES NFTS and is a self-described beeple superfan now…”

Saltz and Schachter were reunited, virtually, earlier this month for “NFTs: Fad or the Future of Art?” an online panel discussion sponsored by the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, now available on YouTube.

Marina Isgro, the museum’s curator of media and performance art, who moderated the event, kicked off the discussion with some much-need definitions. A blockchain, she explains, “is a digital record of transactions distributed across a decentralized network of computers.” A non-fungible token is “a unique piece of data registered on a blockchain that can serve as a surrogate or certificate of authenticity for various kinds of objects in the digital and real worlds.”

On the question of whether NFTs are fad or future, Schachter, speaking from Vienna, opined: “I think they are both and neither at the same time.” Saltz’s sentiments were similar: “As with art, NFTs contain the good, the bad and the very bad,” he says, adding what he has seen so far “are conventional in one of the following ways. They’re either a screensaver, or a kind of GIF, or animation, sci fi, a little male softcore porn of women. Over and over and over, you see the same things.”

“It’s bro culture,” says Claudia Hart, an artist and professor in Chicago, because it grew out of the tech market “and their idea of what’s cool.”

NFTs were a perfect market for cryptocurrencies, Hart says. “Because the currencies need to distribute to accrue value, they seized on art because the art market already existed.”

Some NFT art has a closer tie to internet memes. Nyan Cat, a crude 2011 animated feline with a Pop Tart body flying through space trailing rainbows, first became a popular YouTube video but was reclaimed by its creator, a young Dallas artist named Chris Torres, as an NFT that sold for $587,000 in February.

“There was a trillion dollars of wealth created out of thin air, or on a mainframe in China,” says Schachter of the rise of cryptocurrencies, “and there was nothing you could do with it.

“Then all of a sudden, with NFTs, collectibles, these NBA things, and all of these other things besides the art, suddenly there was something to spend it on, and the well just opened up and flooded and there was a deluge of acquisitions of these things.”

Anne Bracegirdle, head of U.S. sales for fine art shippers Convelio and co-founder of the Art & Antiquities Blockchain Consortium, who was also part of the virtual panel discussion, says it was disappointing that it was the Beeple piece that first introduced many to the idea of NFTs.

“There’s so much good quality work,” she says, it’s too bad the Beeple “resulted in a lot of knee-jerk criticism of what the art is.”

“So much of what’s beautiful behind blockchain digital art is the community behind it,” Bracegirdle says.

The digital work of a number of artists of various backgrounds were cited, including Kevin and Jennifer McCoy, Kevin Abosch, Sarah Friend, Rhea Myers and a Nigerian artist named Osinachi.

“I thought when I first got involved myself, back in September 2020, a lot of it looked like paintings on the back of a van,” Schachter says. “But like everything, you have to look. You really have to do the leg work.”

Hart says artists are drawn to the format because not only does a greater percentage of sales profits go to artists, they also receive a percentage if it is resold—which can give creators a part of any windfall should prices rise.

Bracegirdle says the blockchain technology also provides a solid basis to determine rarity or number of editions. “Simplified transactions, increased transparency, increased trust, increased security, empowered users—all of these elements that guide blockchain can simplify so many processes in the art world that make it difficult to engage, or to be a buyer or a seller or even someone who works in the industry,” she says.

But what is ownership in the world of digital art? Collectors who keep their NFT in their “digital wallets” can view the unique file on their phone or computer, but mostly what they own is the certificate of authenticity, which can be an asset they can resell.

There are environmental concerns with NFTs even though they don’t involve a physical product. The energy required to keep cryptocurrencies going requires plenty of electricity. One cryptocurrency, Ethereum, uses a “proof of work” secure system that uses more energy in a year than the entire country of Denmark.

Still, NFTs are bringing a new audience to the art market.

“I heard from someone at Christie’s that somewhere like 80 percent of their bidders for the Beeple were first-time buyers,” Bracegirdle says. “The Winkelvoss twins were quoted when they bought their first crypto piece that it was the first piece of art they bought because it was the first piece of art they could understand.”

And despite the headline-making exceptions, most crypto art is reasonably priced, Schachter says. “The average price of an NFT is $100. The average price of a good painting that you can find on Instagram is $100. It’s such a misconception to think that art is expensive. Neither art in the traditional form or in the digital form is expensive. Sure, we hear about these stupid cases where they go for crazy prices, but that’s an anomaly.

“You can’t just dismiss something because you’re fearful of change,” Schachter says. “The art world complains a lot, but they’re complaining because they’re losing control. And that’s not something they sit easily with.”

“I hated that the art world had instantaneous negative knee-jerk reaction to it,” Saltz says. “‘Oh, NFTs, they're not real! NFTs aren’t real!’ And you really want to say, they’re as real as the internet, they’re as real as a toothache”

“The general distrust of NFTs in the art world [is] because of this entanglement with cryptocurrency,” says Isgro. “I feel art gets left out of these conversations entirely.” (So far there are no NFTs in the Hirshhorn collection).

As for the future, “I think NFTs will be where painting or sculpture or macrame or any tool is,” Saltz says. “it’s a tool, it’s a medium, it’s a genre. it’s a form. And it depends what people do with them as art.

“So far what I have seen has been pretty meh,” he says. “I’m sure some day there may be a Francis Bacon of NFTs, I don’t know. Everybody said iPad art was impossible, and David Hockney made some pretty good iPad drawings.” Hockney is one of just two artists whose work has fetched more than Beeple’s; the other is Jeff Koons.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/69/a5/69a5e416-c480-4451-a07b-e2117f02a792/longform_mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5e/e5/5ee56ee2-316f-44f2-8574-059e4633c0fe/longform_desktop.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)