The Storied Past and Inspiring Future of the Smithsonian’s Arts and Industries Building

It was once the Institution’s most forward-looking museum. Soon it will be again

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a3/95/a395ce70-a806-4454-a200-b5f567e88e5a/untitled-1.jpg)

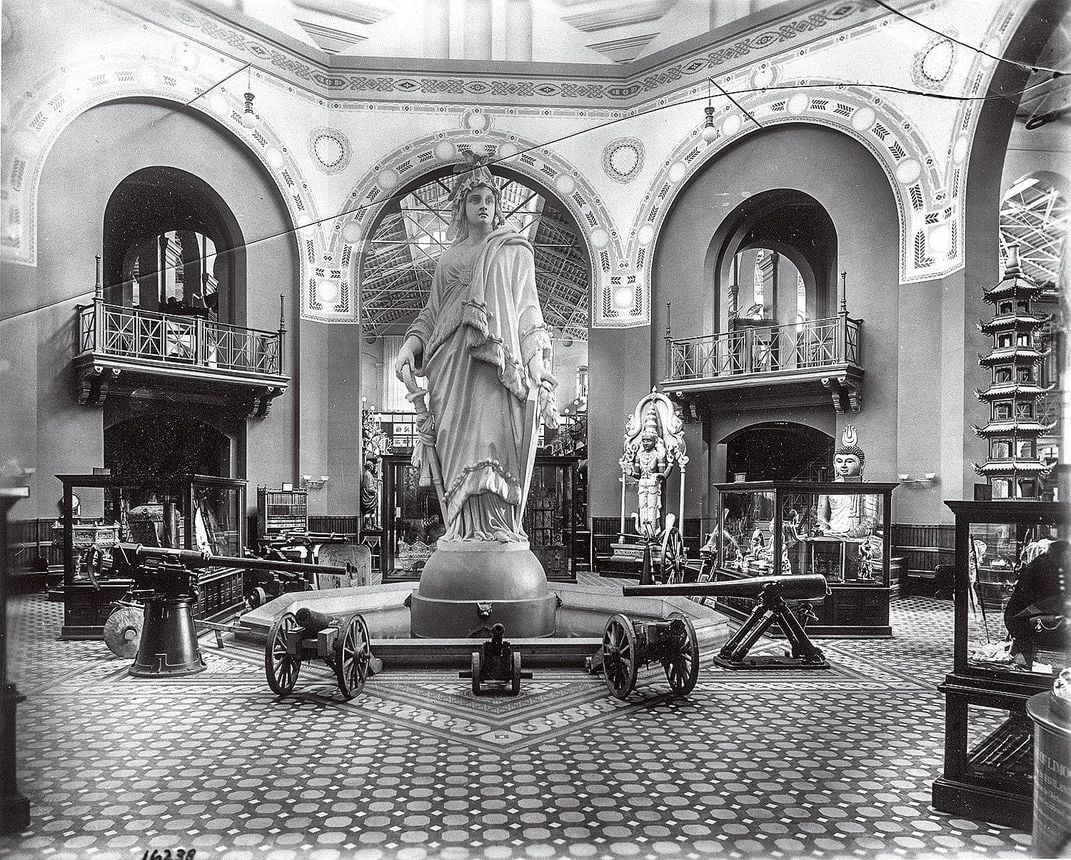

The nation was preparing to celebrate the inauguration of James Garfield in the United States National Museum, today called the Arts and Industries Building. The edifice was not scheduled to debut for several months, so workers moved quickly to install temporary floorboards and thousands of coat racks and hat bins. State flags were hung from above. A statue, America, which resembled the Roman goddess Libertas, was erected in the rotunda beneath the building’s dome, her raised torch lit by a new device, Thomas Edison’s electric light bulb.

On inauguration night—March 4, 1881—guests must have noticed how different this building was from other grand museums. The massive exhibition hall in which they toasted the new president was open, with no walls to divide the space. Overhead were skylights, innovative but perhaps not at their most impressive on this snowy evening.

When the original stewards founded the Smithsonian 175 years ago, in 1846, they envisioned it first as a center for scientific research, second as a repository for items representing American arts and sciences. Most contributions were initially stored in what is known as the “Castle,” the institution’s first building, erected in 1855. Within a couple of decades the Smithsonian was bursting at the seams with acquisitions, necessitating a kind of house cleaning.

Spencer Baird, the institution’s second Secretary, hired an architect named Adolf Cluss, a German immigrant, to design a new building. It borrowed from Moresque, Greek and Byzantine styles. Visitors would be greeted not by imposing marble columns but by a structure on a human scale made of humble, everyday brick, a material that would also reduce the likelihood of runaway fire, which had devastated the Castle and its contents in 1865.

To underline the attitude of openness and accessibility, Baird and Cluss created four entrances—each one barely a step up from the street. “You walk in as a citizen of democracy at ground level.” says Pamela Henson, a historian with the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives. Text posted on walls and cabinets allowed museumgoers to read about objects for themselves—a novelty.

Baird proved a master of showcasing American scientific and technological achievements at the dawn of the Gilded Age. He accomplished one more feat that some regard as a miracle in Washington: He brought the building in on time and under budget.

George Brown Goode, a curator and later the museum’s chief administrator, believed the collections should inspire pride in the American spirit. He helped acquire an astonishing number of items, and soon the museum’s holdings included 60,000 bird specimens, a Neanderthal skull, George Washington’s dress uniform as commander in chief, and an 1830s steam locomotive. “Imagine case after case after case of objects, or gigantic whale skeletons hanging from the ceiling,” say Glenn Adamson, an author and the curator of an exhibition set to open this November. “Just the profusion and the quantitative experience in the AIB in its early years...would have been absolutely mind-blowing.”

And there was much more to come from across the nation: live beehives supplied by the Department of Agriculture; the inaugural gown worn by Helen Taft, wife of the 27th president; the Spirit of St. Louis aircraft flown by Charles Lindbergh; a working model of a coal mine, complete with moving trains; six buffaloes from Montana, “a triumph of the taxidermist’s art”; and a papier-mâché model of a humpback whale sculpted entirely from shredded U.S. currency. Some have called the Arts and Industries Building the incubator for other Smithsonian museums that would spring up over the next 100 years.

There’s reason to believe that the early exhibitions, with their emphasis on technology and industry, presented the world with a new image of the United States. The novelist Christopher Buckley once wrote that the building’s message was, “We’re not just a bunch of heavily armed farmers. We know all about this Industrial Revolution thing.”

For nearly two decades the AIB has been closed for renovation—just repairing the roughly 900 windows, no two exactly the same size, proved monumental—but it reopens this fall, with an exhibition entitled “Futures.” It will stretch from a time that items like the telephone were thought to be wildly futuristic dreams, to present-day pioneering ideas like bioreactors that cleanse the air and a space sail that will propel travelers through the cosmos. “It’s an audacious experiment in how to talk about the future,” says the museum’s director, Rachel Goslins. “It can’t tell you everything, but it can challenge you to envision it for yourself.”

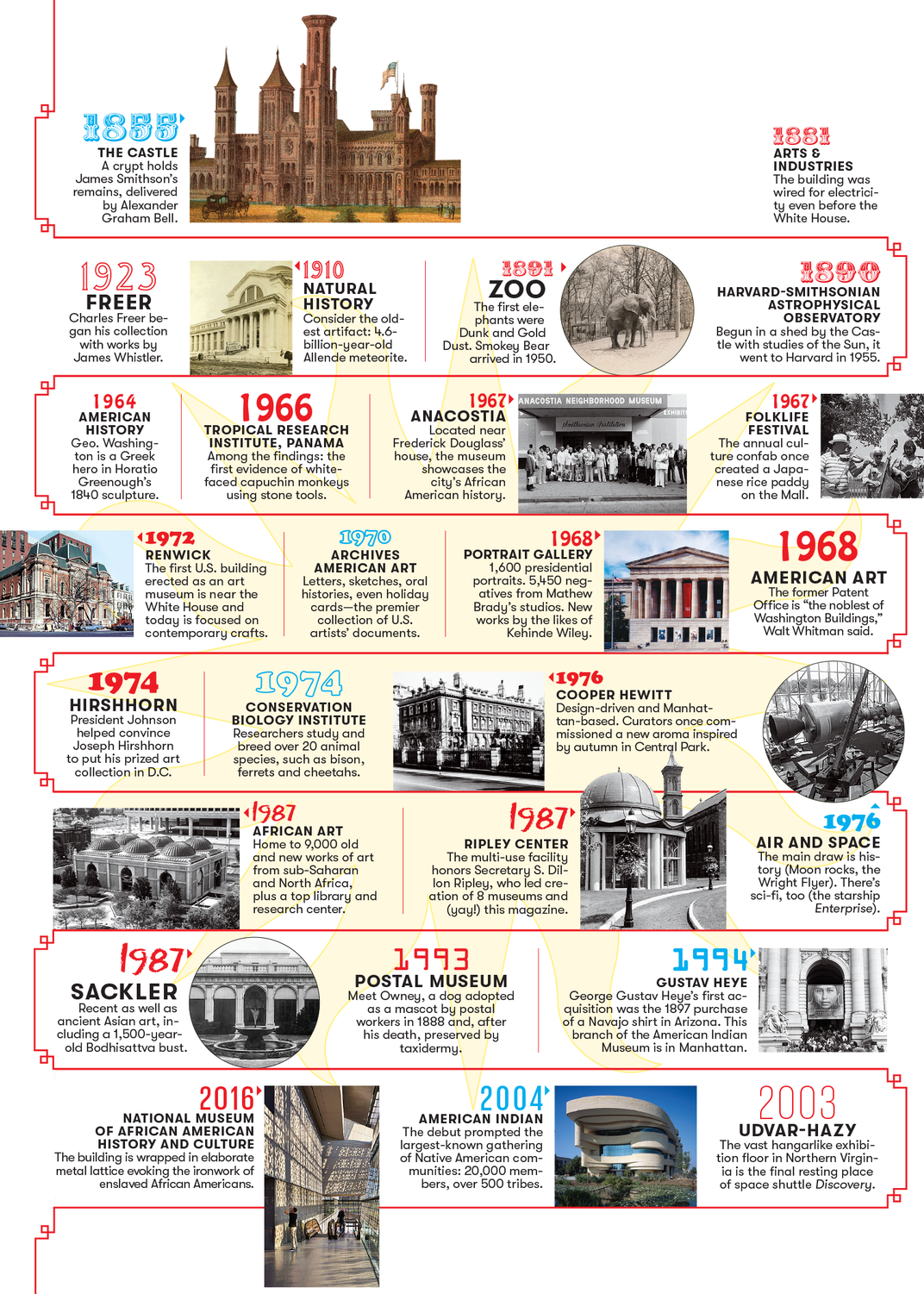

Quite a Legacy

James Smithson never imagined how far his idea would go

Research by Michelle Strange and Gia Yetikyel

*Editor's Note, July 7, 2021: The “Quite a Legacy” graphic was not a comprehensive listing of all Smithsonian research facilities. Among the facilities we omitted are the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (1965), Museum Conservation Institute (1963), Smithsonian Libraries (1866, held at Library of Congress) and Archives (1891) and the Smithsonian Marine Station (1971).