How the Green Book Helped African-American Tourists Navigate a Segregated Nation

Listing hotels, restaurants and other businesses open to African-Americans, the guide was invaluable for Jim-Crow era travelers

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f2/a7/f2a7cd19-78b3-4a09-9515-adf001180870/apr2016_f01_nationaltreasuregreenbook.jpg)

For black Americans traveling by car in the era of segregation, the open road presented serious dangers. Driving interstate distances to unfamiliar locales, black motorists ran into institutionalized racism in a number of pernicious forms, from hotels and restaurants that refused to accommodate them to hostile “sundown towns,” where posted signs might warn people of color that they were banned after nightfall.

Paula Wynter, a Manhattan-based artist, recalls a frightening road trip when she was a young girl during the 1950s. In North Carolina, her family hid in their Buick after a local sheriff passed them, made a U-turn and gave chase. Wynter’s father, Richard Irby, switched off his headlights and parked under a tree. “We sat until the sun came up,” she says. “We saw his lights pass back and forth. My sister was crying; my mother was hysterical.”

“It didn’t matter if you were Lena Horne or Duke Ellington or Ralph Bunche traveling state to state, if the road was not friendly or obliging,” says New York City-based filmmaker and playwright Calvin Alexander Ramsey. With director and co-producer Becky Wible Searles, he interviewed Wynter for their forthcoming documentary about the visionary entrepreneur who set out to make travel easier and safer for African-Americans. Victor H. Green, a 44-year-old black postal carrier in Harlem, relied on his own experiences and on recommendations from black members of his postal service union for the inaugural guide bearing his name, The Negro Motorist Green-Book, in 1937. The 15-page directory covered Green’s home turf, the New York metropolitan area, listing establishments that welcomed blacks. The power of the guide, says Ramsey, also the author of a children’s book and a play focused on Green-Book history, was that it “created a safety net. If a person could travel by car—and those who could, did—they would feel more in control of their destiny. The Green-Book was what they needed.”

The Green-Book final edition, in 1966-67, filled 99 pages and embraced the entire nation and even some international cities. The guide pointed black travelers to places including hotels, restaurants, beauty parlors, nightclubs, golf courses and state parks. (The 1941 edition above resides in the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.)

Mail carriers, Ramsey explains, were uniquely situated to know which homes would accommodate travelers; they mailed reams of listings to Green. And black travelers were soon assisting Green—submitting suggestions, in an early example of what today would be called user-generated content. Another of Green’s innovations prefigured today’s residential lodging networks; like Airbnb, his guide listed private residences where black travelers could stay safely. Indeed, it was an honor to have one’s home listed as a rooming house in the Green-Book, though the listings themselves were minimalist: “ANDALUSIA (Alabama) TOURIST HOMES: Mrs. Ed. Andrews, 69 N. Cotton Street.”

The Green-Book was indispensable to black-owned businesses. For historians, says Smithsonian curator Joanne Hyppolite, the listings offer a record of the “rise of the black middle class, and in particular, of the entrepreneurship of black women.”

In 1952, Green retired from the postal service to become a full-time publisher. He charged enough to make a modest profit—25 cents for the first edition, $1 for the last—but he never became rich. “It was really all about helping,” says Ramsey. At the height of its circulation, Green printed 20,000 books annually, which were sold at black churches, the Negro Urban League and Esso gas stations.

Writing in the 1948 edition, Green predicted, “There will be a day in the near future when this guide will not have to be published. That is when we as a race will have equal opportunities and privileges in the United States.” He died in 1960, four years before Congress passed the Civil Rights Act.

Green’s lasting influence, says Ramsey, “was showing the way for the next generation of black entrepreneurs.” Beyond that, he adds, “Think about asking people to open their homes to people traveling—just the beauty of that alone. Some folks charged a little, but many didn’t charge anything.”

Today, filmmaker Ric Burns is working on his own Green-Book documentary. “This project began with historian Gretchen Sorin, who knows more than anyone about the Green-Book,” says Burns. The film, he says, shows the open road as a place of “shadows, conflicts and excruciating circumstances.”

Washington, D.C.-based architectural historian Jennifer Reut, who created the blog “Mapping the Green Book” in 2011, travels the country to document surviving Green-Book sites, such as Las Vegas, Nevada’s Moulin Rouge casino and hotel, and the La Dale Motel in Los Angeles. Much of her focus, she says, is to look at places “in the middle of nowhere. That is where it was much more dangerous for people to go.”

Related Reads

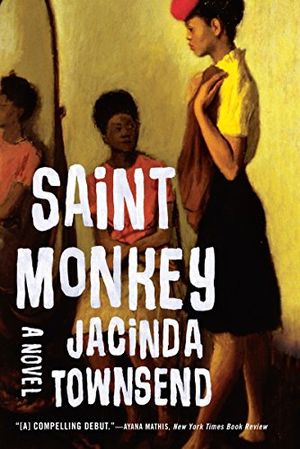

Saint Monkey: A Novel