History Shows Americans Have Always Been Wary of Vaccines

Even so, many diseases have been tamed. Will Covid-19 be next?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/95/12/9512ed5b-a2ad-4a6e-83b4-a664d7b69066/146958001.jpg)

As long as vaccines have existed, humans have been suspicious of both the shots and those who administer them. The first inoculation deployed in America, against smallpox in the 1720s, was decried as antithetical to God’s will. An outraged citizen tossed a bomb through the window of a house where pro-vaccination Boston minister Cotton Mather lived to dissuade him from his mission.

It did not stop Mather’s campaign.

After British physician Edward Jenner developed a more effective smallpox vaccine in the late 1700s—using a related cowpox virus as the inoculant—fear of the unknown continued despite its success in preventing transmission. An 1802 cartoon, entitled The Cow Pock—or—the Wonderful Effects of the New Innoculation, depicts a startled crowd of vaccinees who have seemingly morphed into a cow-human chimera, with the front ends of cattle leaping out of their mouths, eyes, ears and behinds.

Paul Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, says the outlandish fiction of the cartoon continues to reverberate with false claims that vaccines cause autism, multiple sclerosis, diabetes, or that the messenger RNA-based Covid-19 vaccines from Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna lead to infertility.

“People are just frightened whenever you inject them with a biological, so their imaginations run wild,” Offit recently told attendees of “Racing for Vaccines,” a webinar organized by the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

“The birth of the first anti-vaccine movement was with the first vaccine,” says Offit. People don’t want to be compelled to take a vaccine, so “they create these images, many of which obviously are based on false notions.”

“There’s a history of the question of how you balance individual liberty—the right to refuse—versus the policing of the public health,” agrees Keith Wailoo, a medical historian at Princeton University and another panelist at the event.

Because vaccines are given to otherwise healthy people that always brings an element of fear into the picture, says Diane Wendt, a curator in the museum’s division of medicine and science.

Wendt and her colleagues have been holding webinars under the moniker “Pandemic Perspectives.” The online panel discussions provide a vehicle to show off some of the museum’s images and artifacts while the building remains closed in Washington, D.C., during the Covid-19 pandemic. Experts provide context to the various topics, says Arthur Daemmrich, director of the museum’s Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation. “Racing for Vaccines” highlighted centuries of scientific progress and technological innovation, which has persisted even in the face of vaccine hesitancy. Of all the diseases for which humans have developed vaccines, only smallpox has been almost fully vanquished on Earth. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) says 14 other diseases that used to be prevalent in the U.S. have been quashed by vaccination.

After smallpox, vaccine efforts around the globe focused on diseases that were decimating livestock—the lifeblood of many economies. The French scientist and physician Louis Pasteur had by the late 1870s come up with a method to vaccinate chickens against cholera. He then moved on to help develop an anthrax vaccine for sheep, goats and cows in 1881. A few years later, Pasteur had come up with the first vaccine to protect humans against rabies, which by 1920 required one shot a day for 21 days.

Early vaccines relied on developing science. When the influenza pandemic of 1918 crashed down on the world, no one had the ability to visualize viruses. Bacteria cultured from victims’ lungs was erroneously thought by leading scientists to be the cause of the illness, says John Grabenstein, the founder of Vaccine Dynamics and a previous director of U.S. Department of Defense Military Vaccine Agency.

Researchers created flu vaccines that failed because they targeted bacteria, not the true viral cause. The viruses weren’t isolated until the 1930s and the first inactivated flu virus for widespread use was not approved until 1945. By contrast, the Covid-19 vaccine went from genetic sequence to near-complete clinical trials, full scale production and delivery to Americans within eight or nine months.

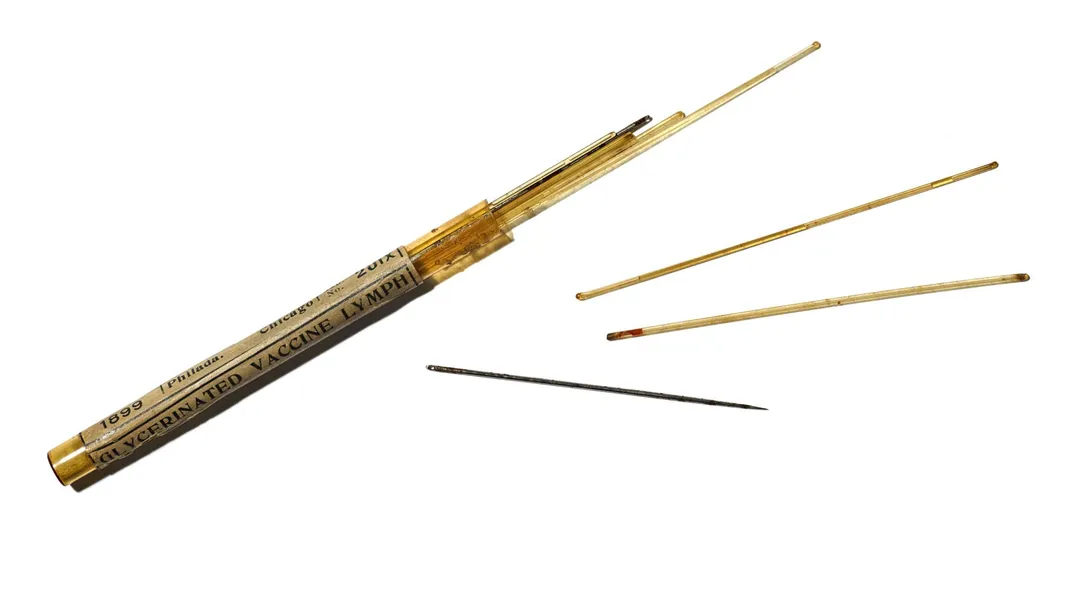

The technology has come a long way. Early smallpox inoculation required scraping out material from a pustule or a scab of someone who had been vaccinated and then scratching it into someone else’s arm, using a hollowed-out needle or something like the spring-loaded vaccinator device from the 1850s that can be found in the museum’s collections. A bifurcated needle that delivers a tiny amount of vaccine subcutaneously is still used today.

In the 1890s, the development of an antitoxin to treat diphtheria gave rise to the pharmaceutical industry and to a regulatory infrastructure to help ensure the safety of drugs. Diphtheria led to sickness and death when toxins emitted by the Corynebacterium diphtheriae bacteria coated the lungs and throat, giving rise to its common name, the “strangling angel.” Between 100,000 to 200,000 American children contracted the illness each year, and 15,000 died.

The New York City Health Department was a leader in diphtheria antitoxin production in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Scientists gave horses ever-increasing doses of toxins; the animals in turn produced antitoxins, which were harvested by bleeding the horses. The horse serum was purified and then administered to children. It helped prevent disease progression and conferred some short-term immunity, says Wendt.

“The impact of this particular product, the antitoxin, in the 1890s was huge,” she says.

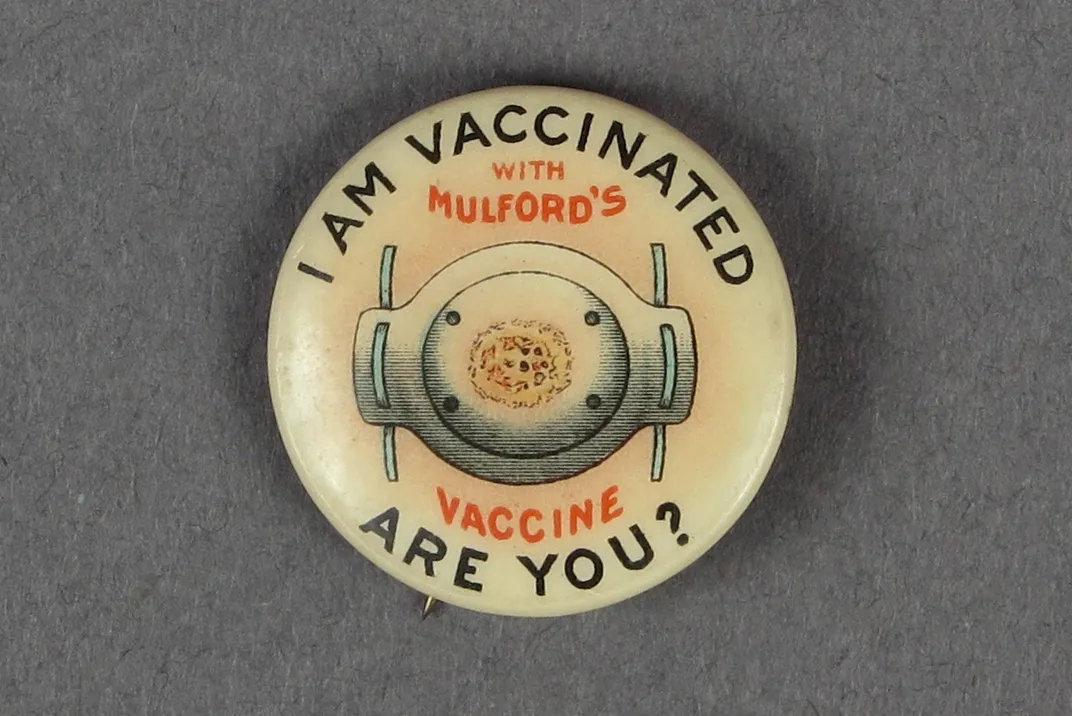

Several drug companies—including H.K. Mulford Co., which also manufactured a smallpox vaccine, and Lederle, founded in 1906 by a former New York health commissioner who had been active in the agency’s diphtheria efforts—commercialized the antitoxin. But tragedy struck. The St. Louis health department allowed contaminated antitoxin serum from one of its horses—who had died of tetanus—to be distributed. Twenty-two children died.

That led to the Biologics Control Act of 1902, which set the stage for federal regulation of vaccines with the establishment of the Food and Drug Administration.

However, as seen through history, “getting vaccines to their destination is a continuing challenge,” says Wailoo. In 1925, Nome, Alaska, experienced a diphtheria outbreak. The town was snowbound. Twenty mushers and 150 sled dogs, including the famous lead dog Balto, relayed antitoxin across the state to Nome, helping to end the epidemic.

“We don’t have dog sleds to deal with today,” says Grabenstein, but the ultra-cold temperatures of -70 degrees Celsius/-94 degrees Fahrenheit required for transport and storage of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine is a high hurdle.

Before Covid-19, the largest nationwide emergency effort to eradicate a disease came in the 1950s, when the polio virus reached a peak of almost 60,000 cases, fomenting anxiety across America. Children experienced paralysis, disability and death. Jonas Salk—who helped develop the influenza vaccine—created a new, equally important vaccine for polio. It was tested in one of the largest-ever trials, involving 1.8 million children, who were known as the Polio Pioneers, says Offit.

When Salk announced on April 12, 1955, that it was “safe, potent and effective,” the vaccine was approved within hours and rolled out immediately, Offit says. “This was Warp Speed One,” he says, playing off the Operation Warp Speed program that aided development of the Covid-19 vaccines.

Ultimately, for vaccines to work, they have to be administered. Public health officials in 1970 encouraged rubella vaccination for children with posters that stated that “Today’s little people protect tomorrow’s little people.” That’s because pregnant women who contract rubella are at risk for miscarriage or stillbirth. “This speaks to communal responsibility,” says Wendt, noting that many campaigns have aimed to motivate Americans to accept vaccines to protect not just themselves, but society at large.

In the past, some pharmaceutical companies—such as Mulford—have produced stickers and buttons that allow the wearer to declare they’ve been vaccinated. The CDC has created stickers that lets Covid-19 recipients tell the world they got their shot.

But many Americans—especially people of color—are still skeptical. “The African American community, for good reason, unfortunately, has seen a legacy of disparate care, of lack of care, including several high-profile incidents like Tuskegee and others where they feel the medical system abandoned them,” says Daemmrich. In the Tuskegee experiment, government researchers studied black men with syphilis and told them they were being treated, but they were not receiving any therapies. The men were never offered proper treatment, either.

“There’s a lot of distrust,” Daemmrich says, adding, “it’s not entirely clear how you overcome that distrust,” but that, “just showing up now in the midst of the pandemic and saying ok trust us now isn’t the way to do it.”

The Kaiser Family Foundation has been tracking hesitancy around the Covid-19 vaccine. In December, before the two vaccines had been distributed, 35 percent of black adults said they would definitely or probably not get vaccinated, compared to 27 percent of the public overall. About half of those black adults said they didn’t trust vaccines in general or that worried they would get Covid-19 from the vaccine. By January this year, Kaiser found that while about 60 percent of black respondents said they thought vaccines were being distributed fairly, half said they were not confident that the efforts were taking the needs of black people into account.

Early data on the vaccine rollout confirms some of those fears. Kaiser found that in more than a dozen states, vaccinations in black Americans were far lower than for white Americans and not proportionate to black people’s share of case counts and deaths.

And, few people alive now have seen anything comparable in terms of the scale of the Covid-19 pandemic, says Wailoo. “Maybe the scale of this is enough of an incentive,” he says.

Offit isn’t as certain. “We saw polio as a shared national tragedy—it pulled us all together,” he says. “It’s harder to watch what goes on today, where it feels like we’re not getting together, rather just more finger-pointing.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)