History’s Selfies: Looking at Artists Looking at Themselves

National Portrait Gallery closes out 50-year anniversary celebration after widening the view to include more women, diverse backgrounds and emerging media

Artists have been doing self-portraits for centuries, looking deeply, carefully depicting and declaring how they wanted to be seen in public.

So when it came time for the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery to assemble its final exhibition of its 50th anniversary year, it was time for a similar institutional self-reflection.

With more than 650 self-portraits in its collection to choose from, its new “Eye to I: Self-Portraits from 1900 to Today” reflects a wider, more diverse and inclusionary America than before.

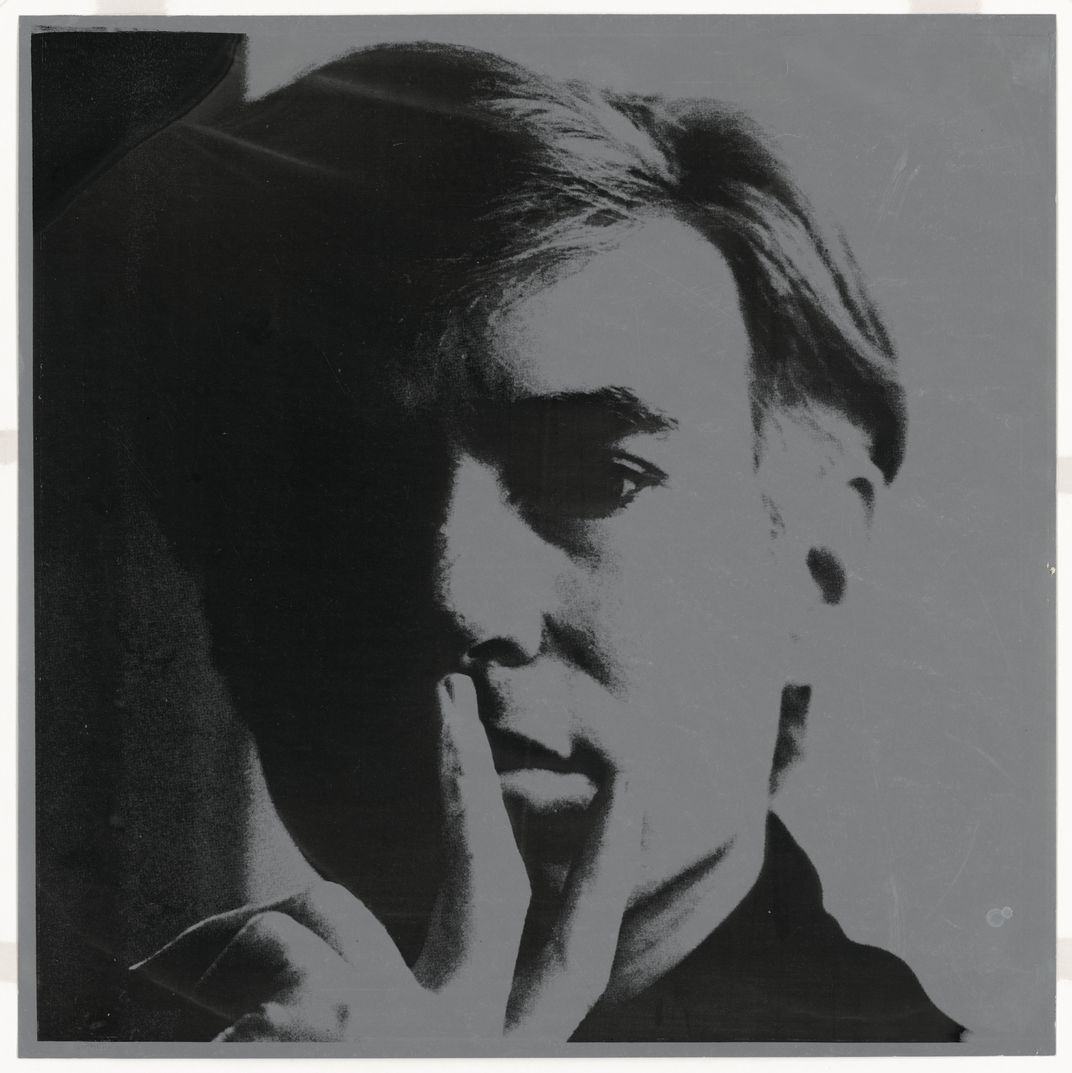

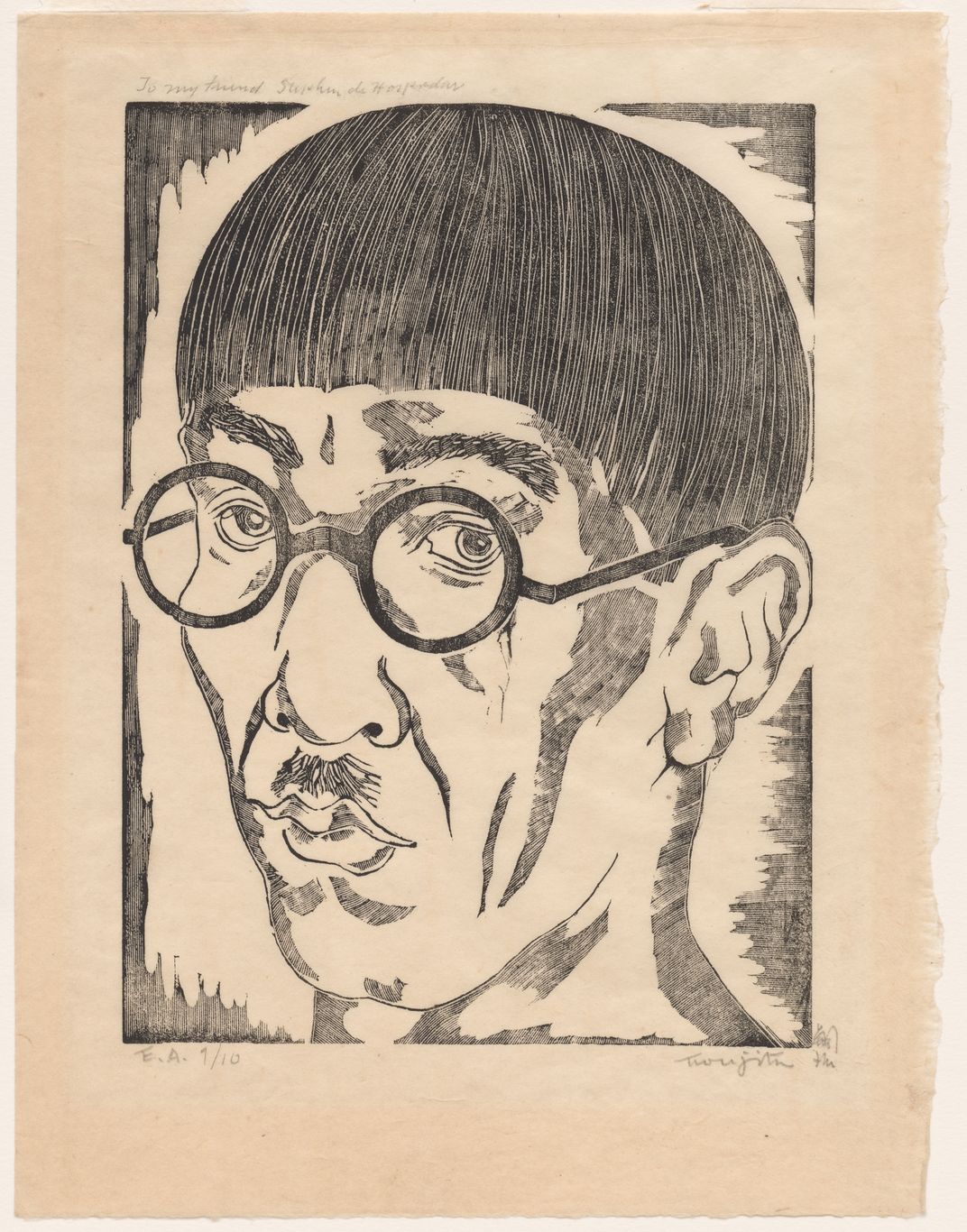

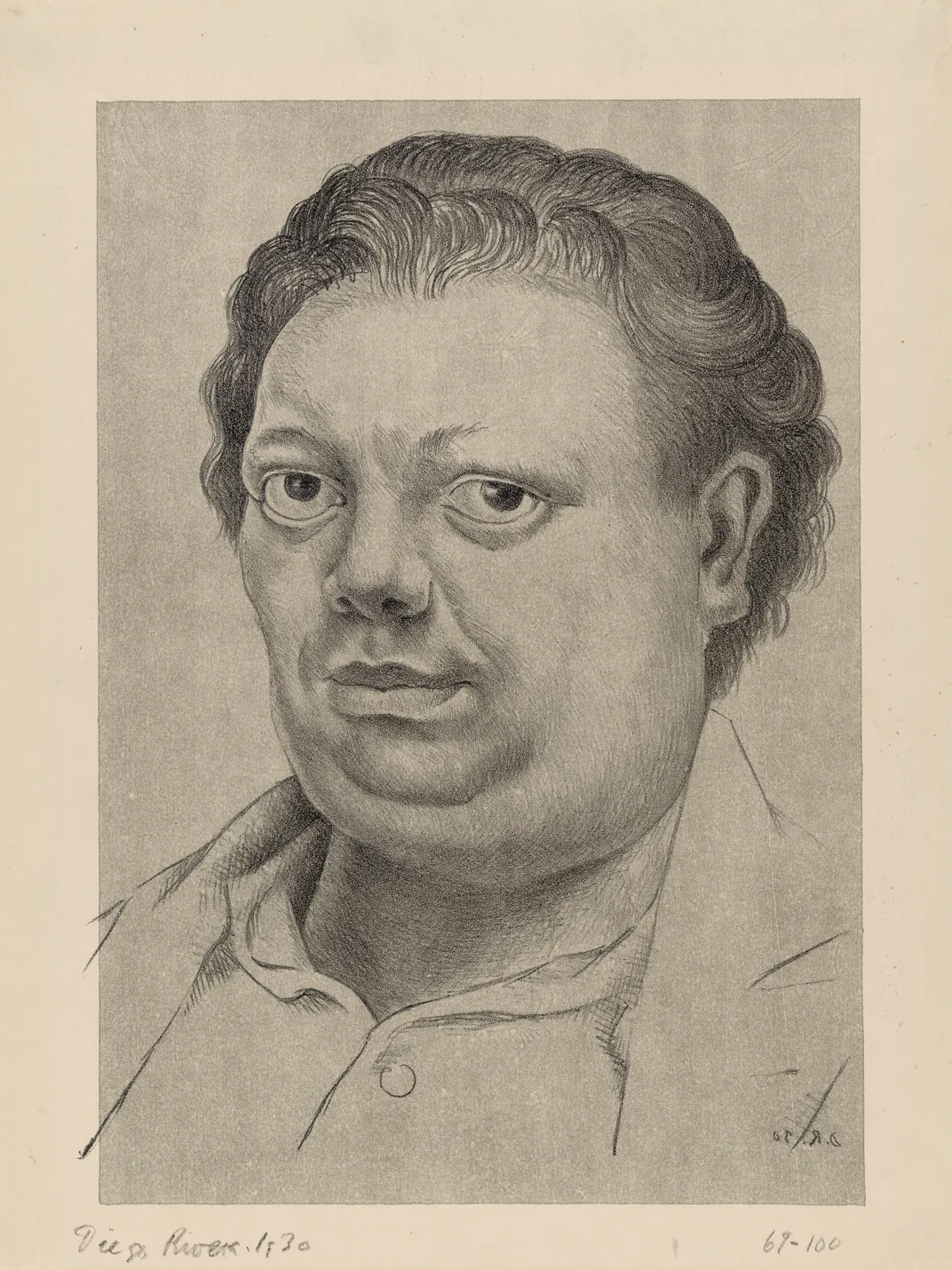

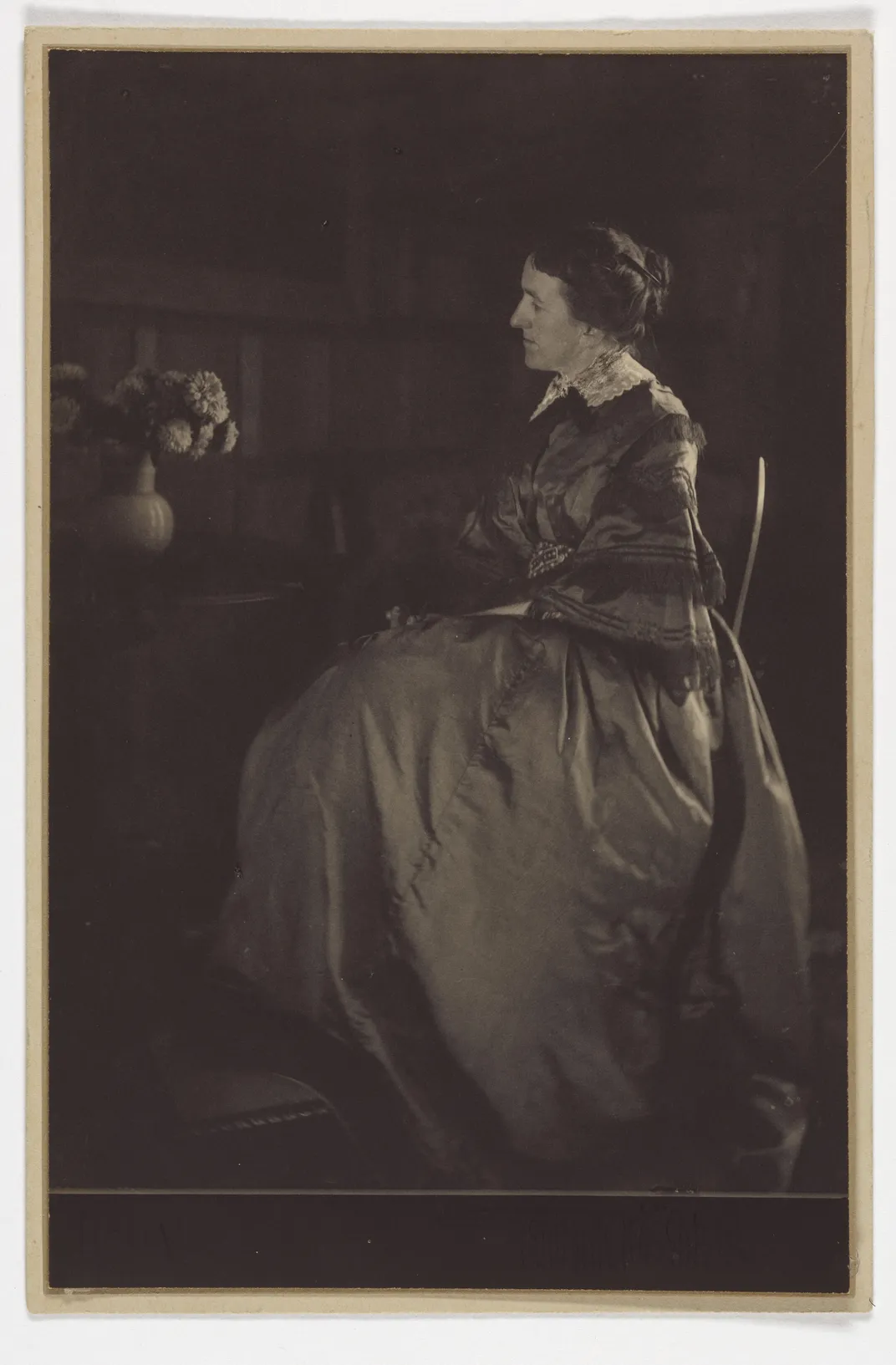

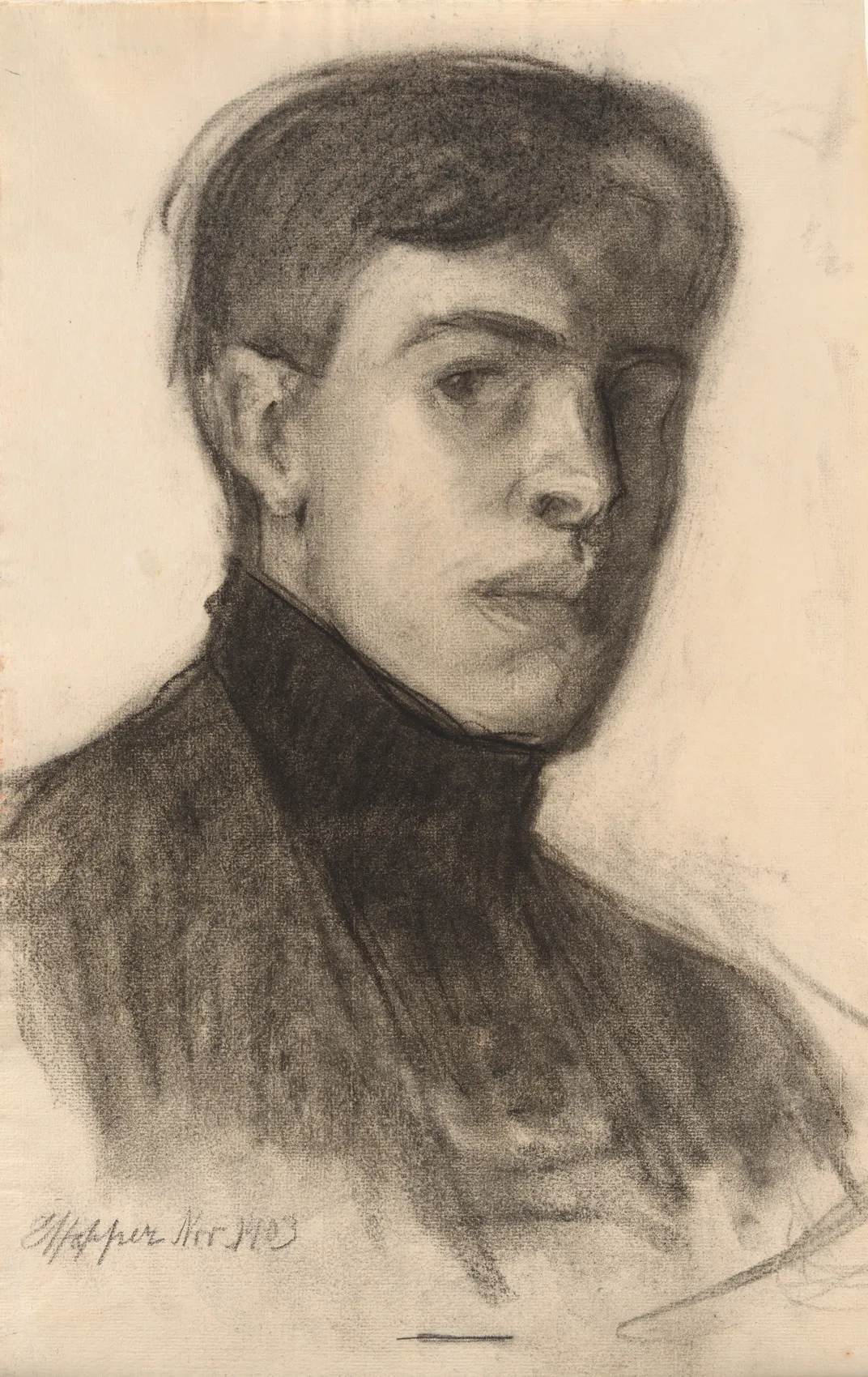

There is the expected array of well-known male artists, from a silvered Andy Warhol, to a 21-year-old Edward Hopper in charcoal, a bemused Diego Rivera in a 1930 lithograph and a wall-sized 16-part Chuck Close in large format photographs from 1989. But roughly a third of the works are by women, from early photojournalist Jessie Tarbox Beals, from the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, where she was the only woman to receive photo credentials, to portraitist Alice Neel, presented in a surprising nude as an 80-year-old.

Chief curator Brendon Brame Fortune, who organized the show—and a separate, traveling version that goes out next year—calls the Neel “one of my favorite works in the collection.”

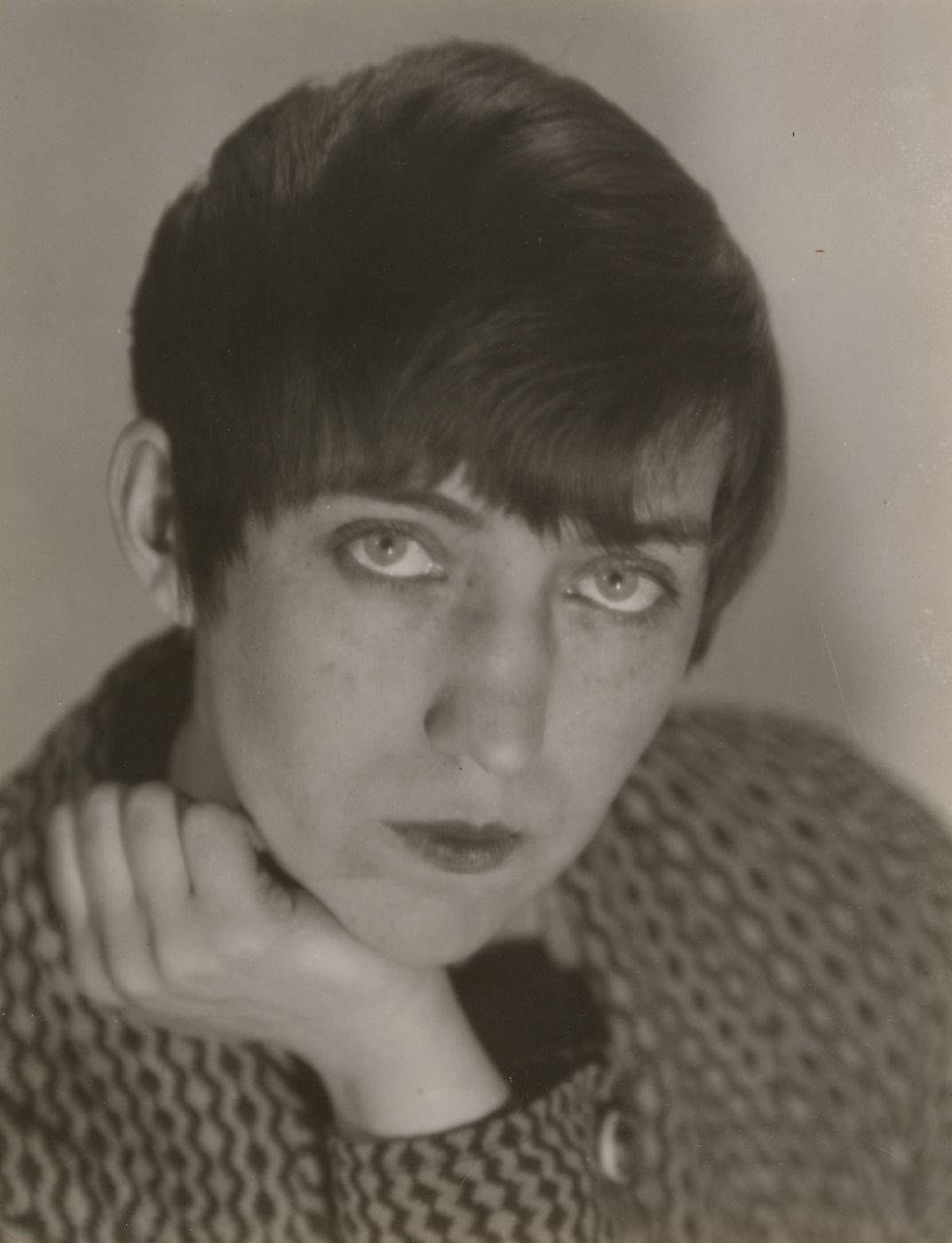

One of only two self-portraits she did in her long life, Neel began it at age 75 and completed it when she was 80, Fortune says. “She references her life as an artist,” she says, “but what she’s done, she’s taken the entire tradition of painting the female nude, which was usually done by a man, and she’s flipped the whole thing.”

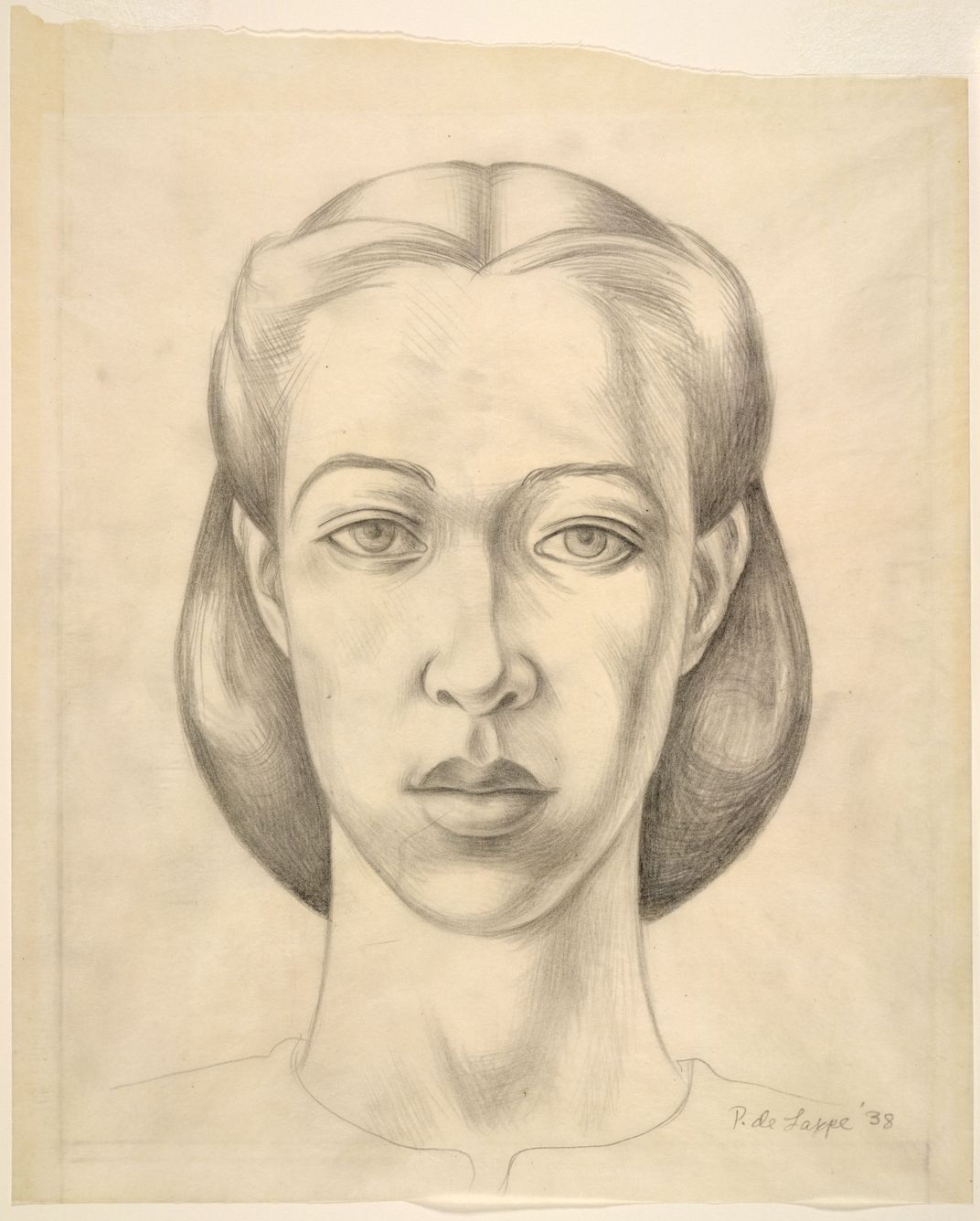

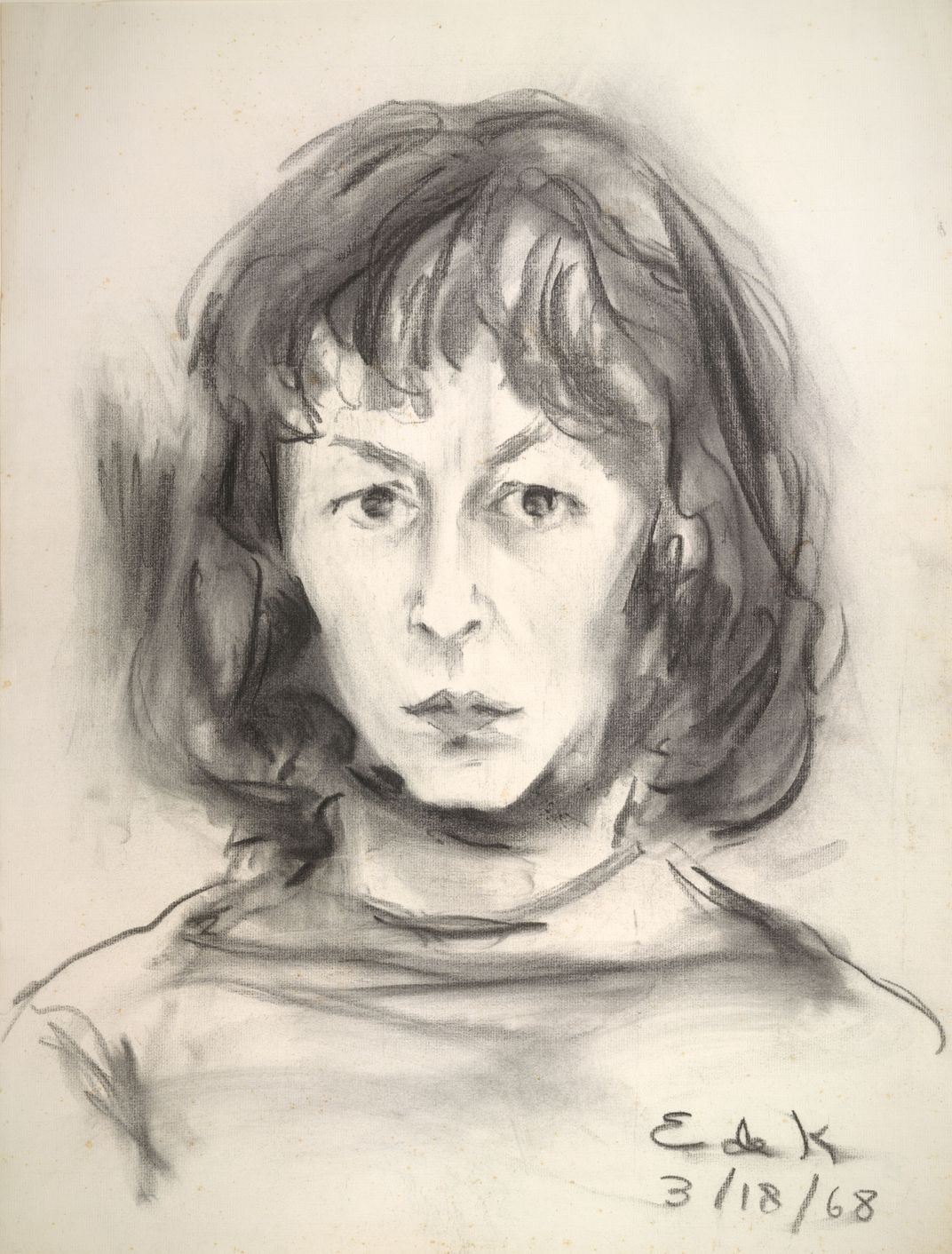

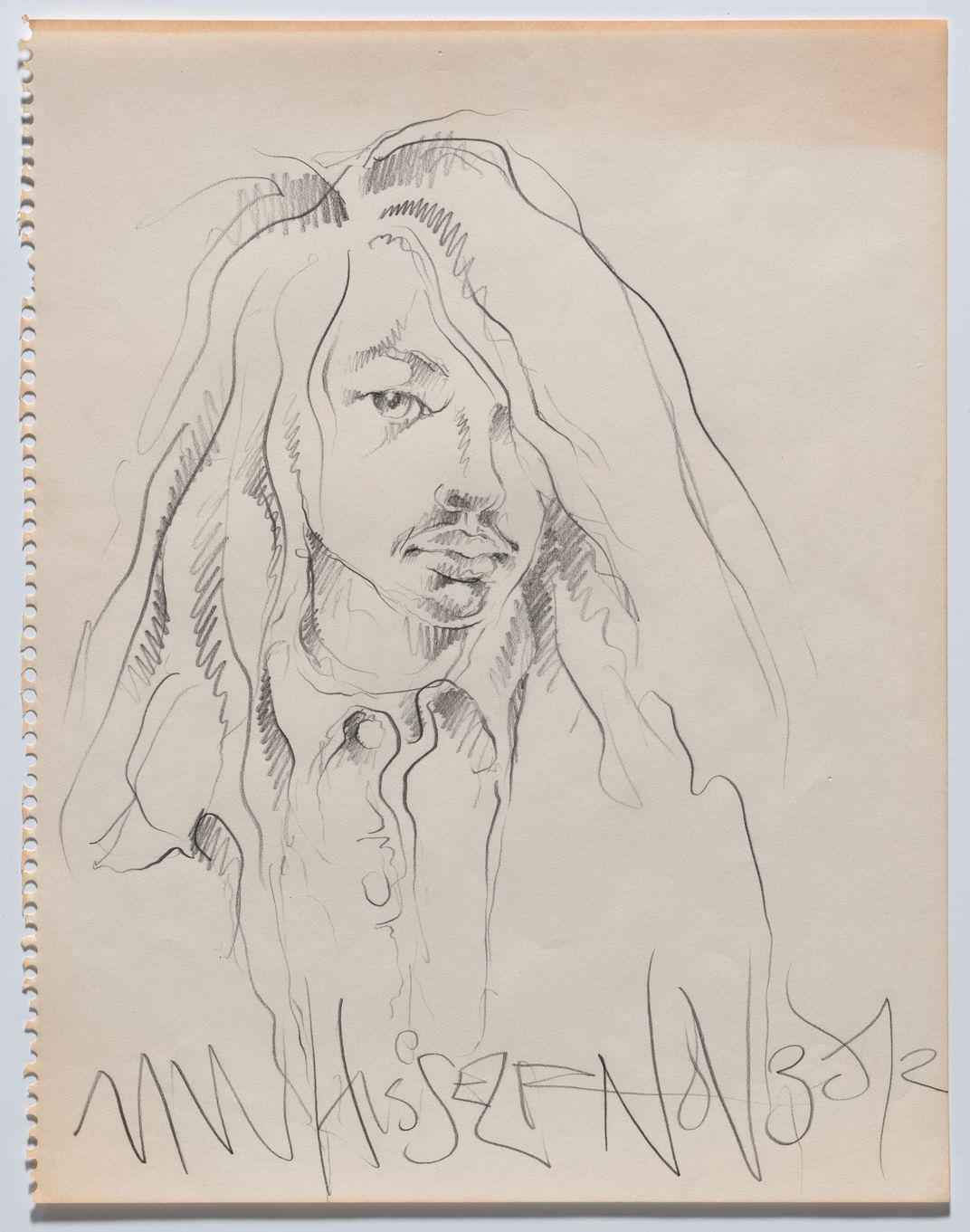

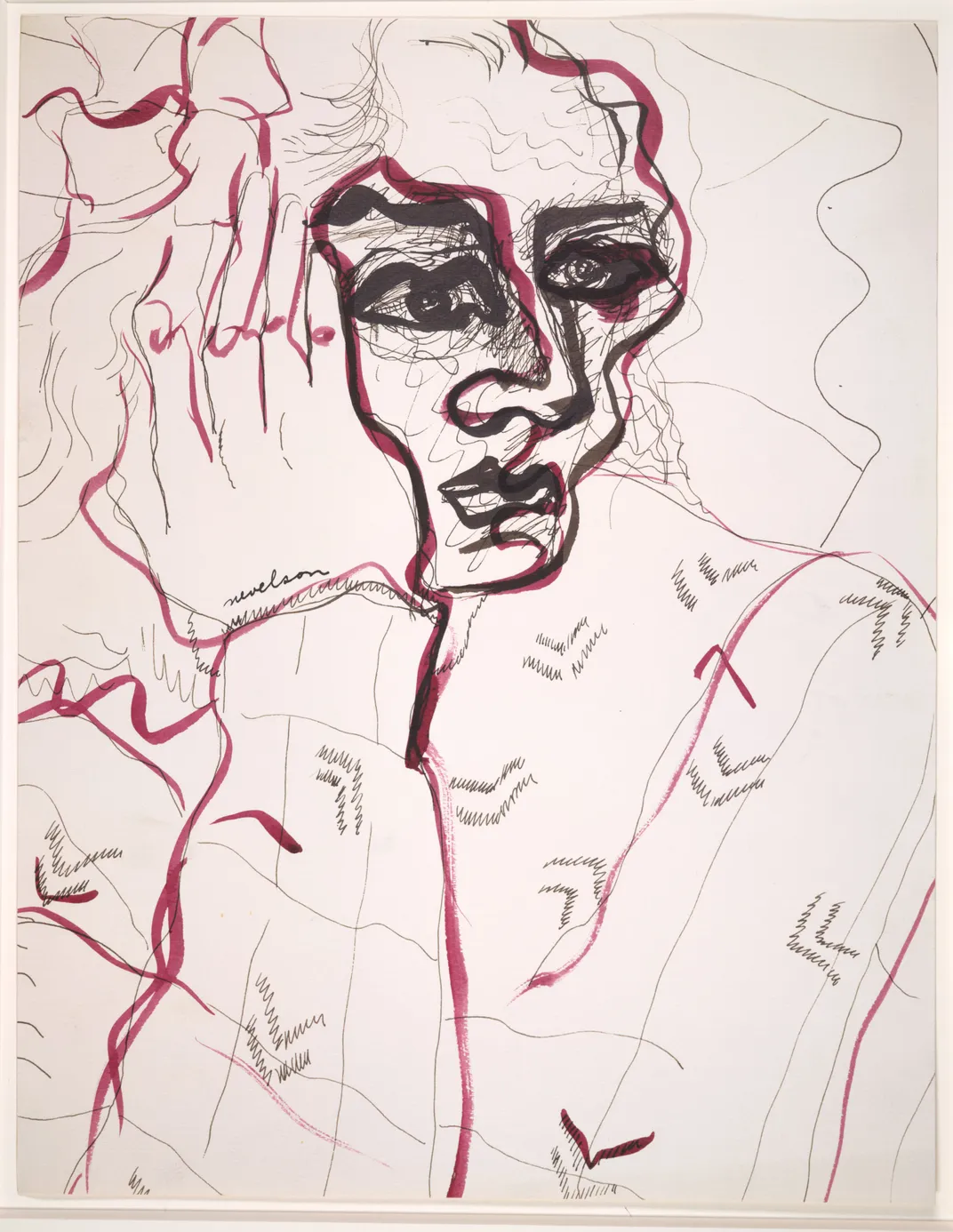

Neel’s acceptance of her own aging body has “become her legacy,” Fortune says. And there are other works in the show where the artists may have aging on their mind, from a pensive Elaine de Kooning charcoal from 1968, six days after turning 50. “This was a time in her life when she was in transition,” Fortune says. Though her hair was short at the time, she rendered herself with longer hair she had decades earlier. “I think she’s rejecting a present face . . . in the past that she sees.”

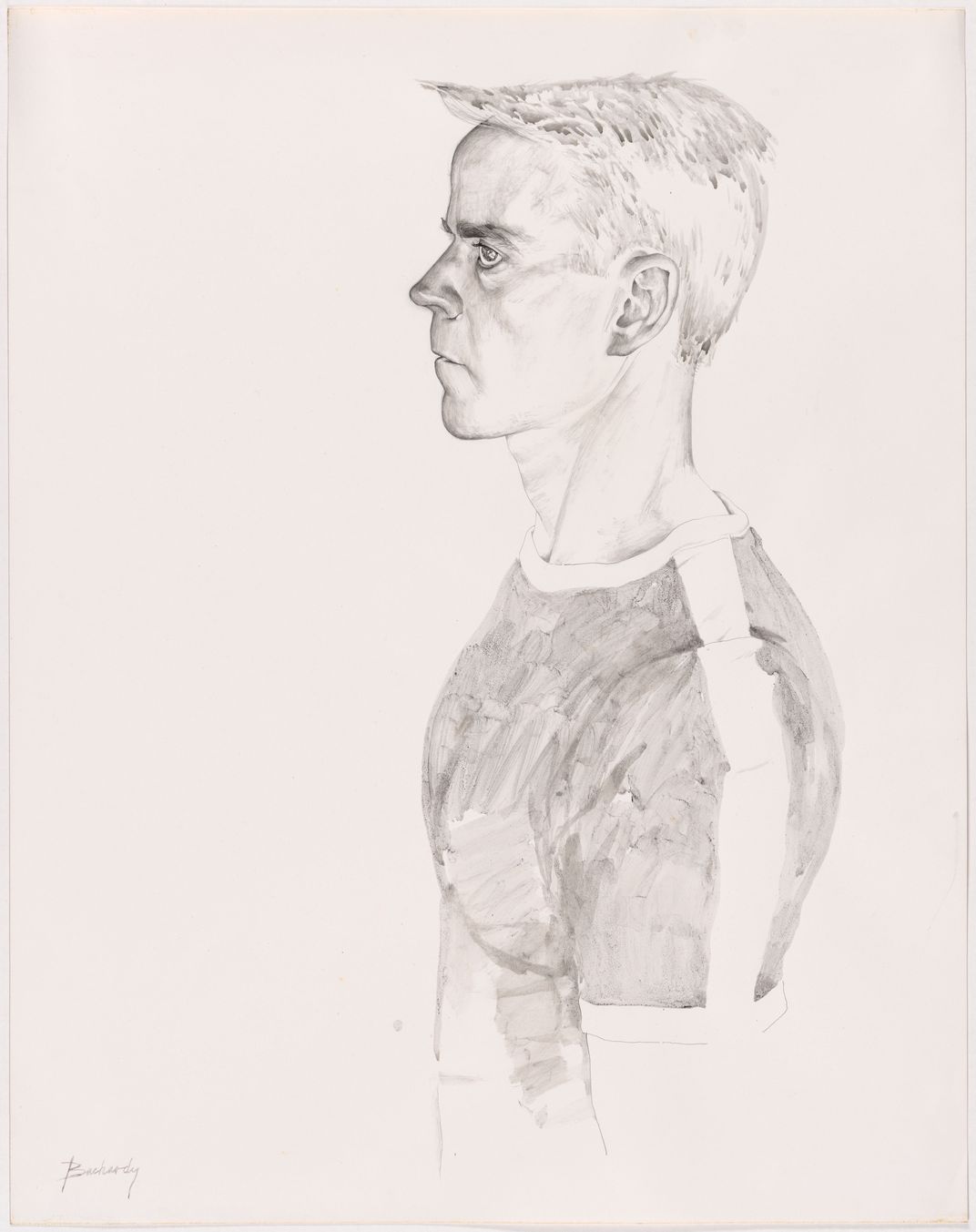

A 1965 self-portrait crayon drawing by Paul Cadmus at age 60, too, may be looking back wistfully at better days. “It’s a very subtle, very sensitive drawing,” Fortune says.

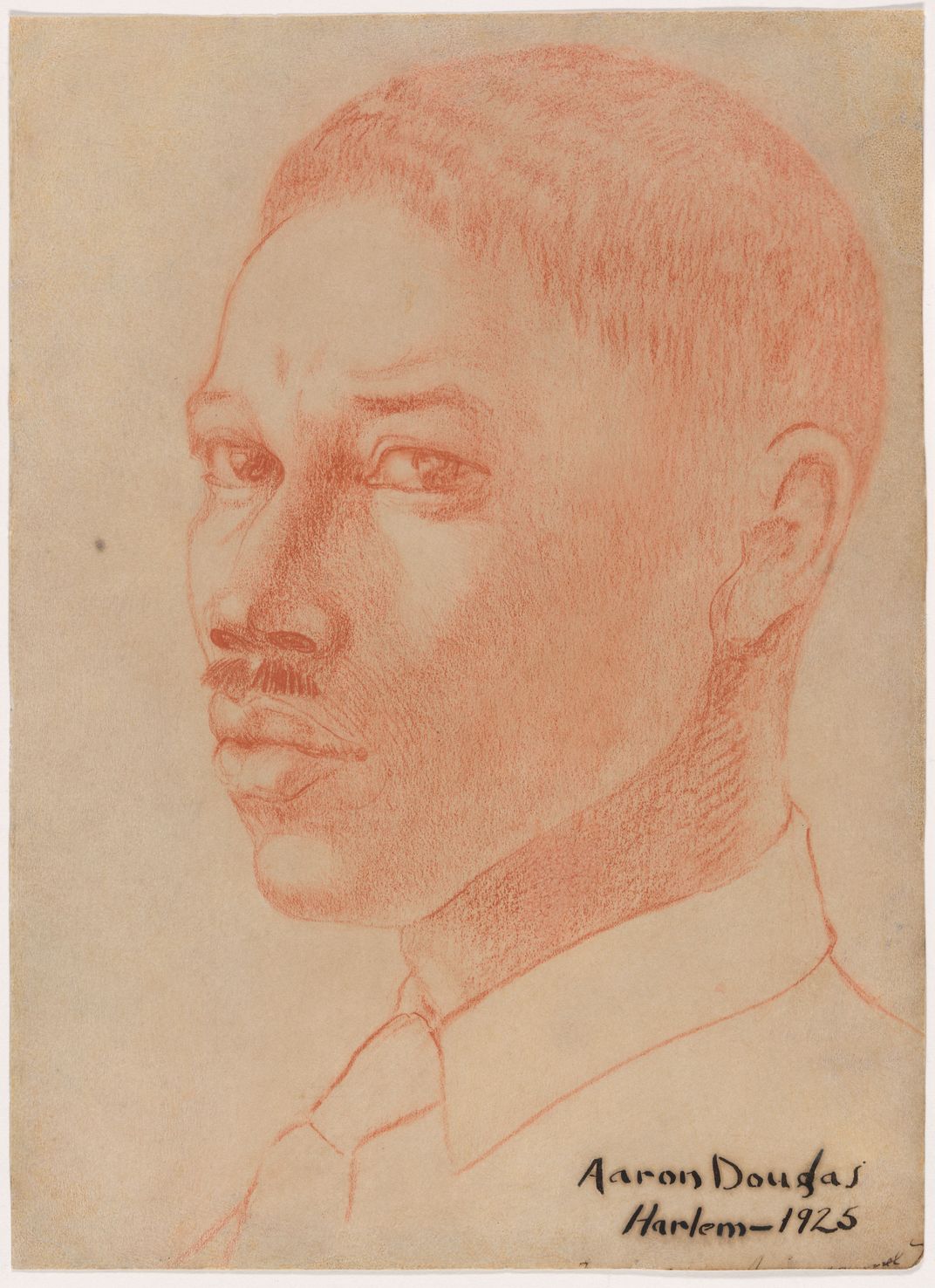

Aaron Douglas purposely used red Conté crayon on paper for his 1925 self-portrait because it had also been used by past masters such as Delacroix. Best known for murals at Fisk University, the Harlem Renaissance artist is “showing us his mastery of the artists of the past as he moves forward into the future. He’s asserting himself in the midst of Jim Crow America.”

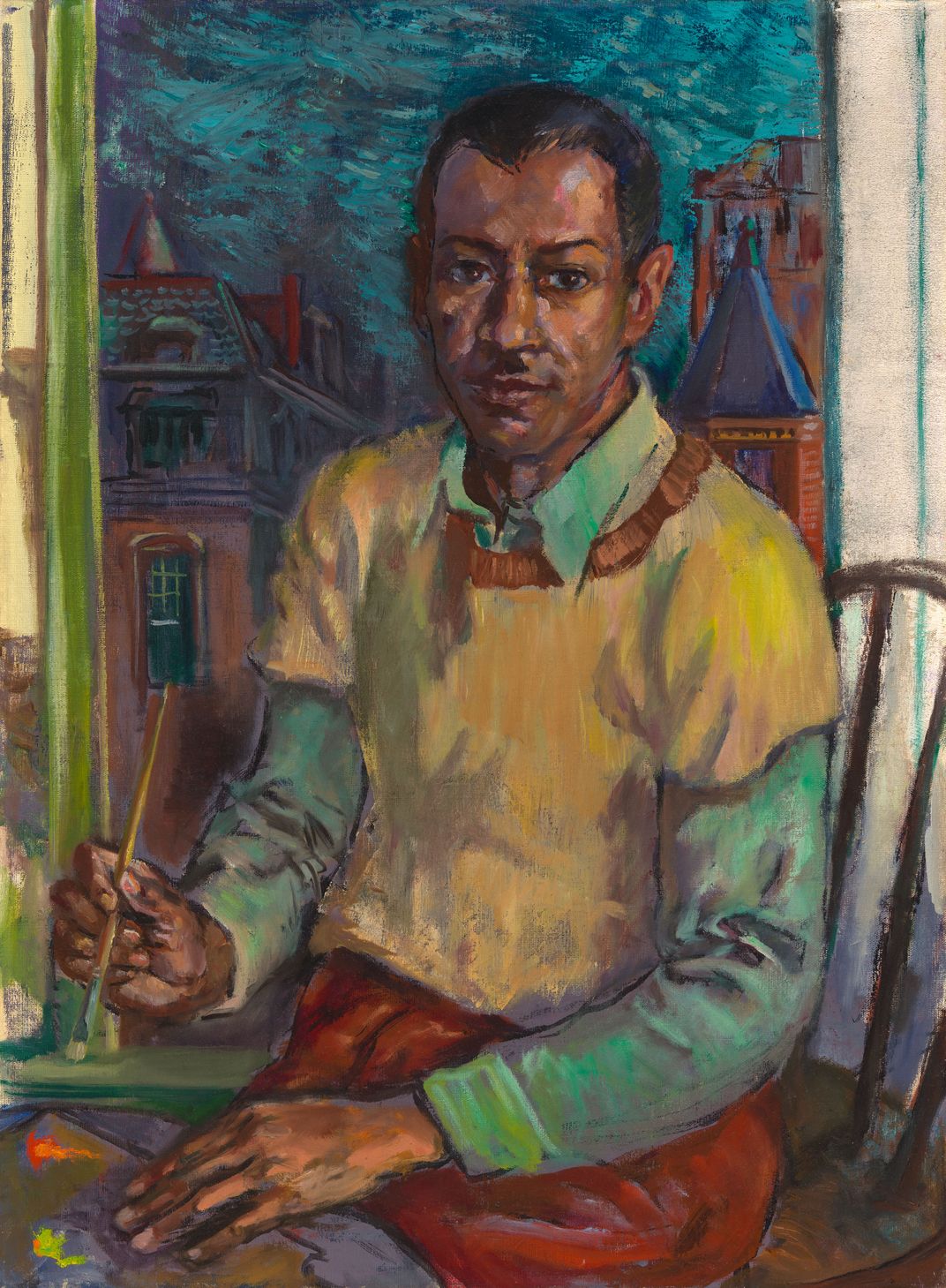

Other African-American artists in the exhibition include James Amos Porter, who literally wrote the first book on it, Modern Negro Art, in 1943. His oil on canvas is one of the rare artist self-portraits in the exhibition to show him among the tools of his trade, paints, with Howard University, where he taught for more than 40 years, prominent behind him.

The splashier oil portrait of Thomas Hart Benton from 1924 may have more wishful thinking behind it, Fortune says. It was first thought to be a marriage portrait with his wife Rita Piacenza, whom he wed in 1922. Subsequently, scholars studying Benton’s work and his affinities for Hollywood, found that it was probably done two years later. “Partly because Rita’s bathing costume is very stylish and up to the minute,” Fortune says, “but also because Benton, who loved the movies, is posing in a way that may reference Douglas Fairbanks Jr.’s role in “The Thief of Baghdad, which came out in 1924.”

Not everything in “Eye to I” is two dimensional. Grant Wood represents himself in a three-inch bronze of his smiling face from early in his career, circa 1925. “He made a number of these in plaster and gave them to friends,” Fortune says. “This was cast later.”

Much larger is Patricia Cronin’s seven-foot bronze, Memorial to a Marriage depicting the artist with her now-wife Deborah Kass, in the style of a 19th-century mortuary sculpture.

New media is reflected eventually, through a 1972 video from Joan Jonas, Left Side Right Side, and in the Internet Cache Portrait of Evan Roth, a Maryland-born artist now based in Germany, who reveals himself by reproducing everything he saw on the internet over a six week period this summer, printing it out on a ribboned, 60-foot long roll of vinyl.

“He calls it a nude self-portrait because it shows us everything he’s thinking and looking at on the web—personal, private and putting it out there for all of us to see,” Fortune says. “And remember, he’s in Berlin, so there’s a lot of images of Angela Merkel.”

A 2017 Instagram and internet video by the artist Amalia Soto, working under the name Molly Soda, shows her to take on a part of a young girl weeping over something she sees on her phone, and then doing a selfie of her sorrow. “She’s crying, but then she’s looking at the phone and she begins to preen a little bit, using the phone as a mirror, as artists who make self-portraits have done for centuries,” Fortune says, “but then she uses the phone as a camera to make a self-portrait of herself for later use.”

As National Portrait Gallery director Kim Sajet says, “We do indeed address the question of the selfie” —that most common explosion of self-portraiture in the culture. “We’re very excited that this is an incredibly diverse exhibition,” Sajet says, “not only in terms of media, but also in terms of gender, and in terms of racial and sociological identity. We have a huge range of people who have done their self -portrait.”

“We also hope that this sampling of how artists have approached the exploration of representations of self leads to a question for all of us,” she says, “on how we think about our own identity.”

“Eye to I: Self-Portraits from 1900 to Today” continues through August 18, 2019 at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cb/93/cb935f9c-90d2-4e73-b59c-cb06d945c013/npg_85_19-neel-r.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)