Home Is Where the Corpse Is—at Least in These Dollhouse Crime Scenes

Frances Glessner Lee’s “Nutshell Studies” exemplify the intersection of forensic science and craft

The “godmother of forensic science” didn’t consider herself an artist. Instead, Frances Glessner Lee—the country’s first female police captain, an eccentric heiress, and the creator of the “Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death”—saw her series of dollhouse-sized crime scene dioramas as scientific, albeit inventive, tools.

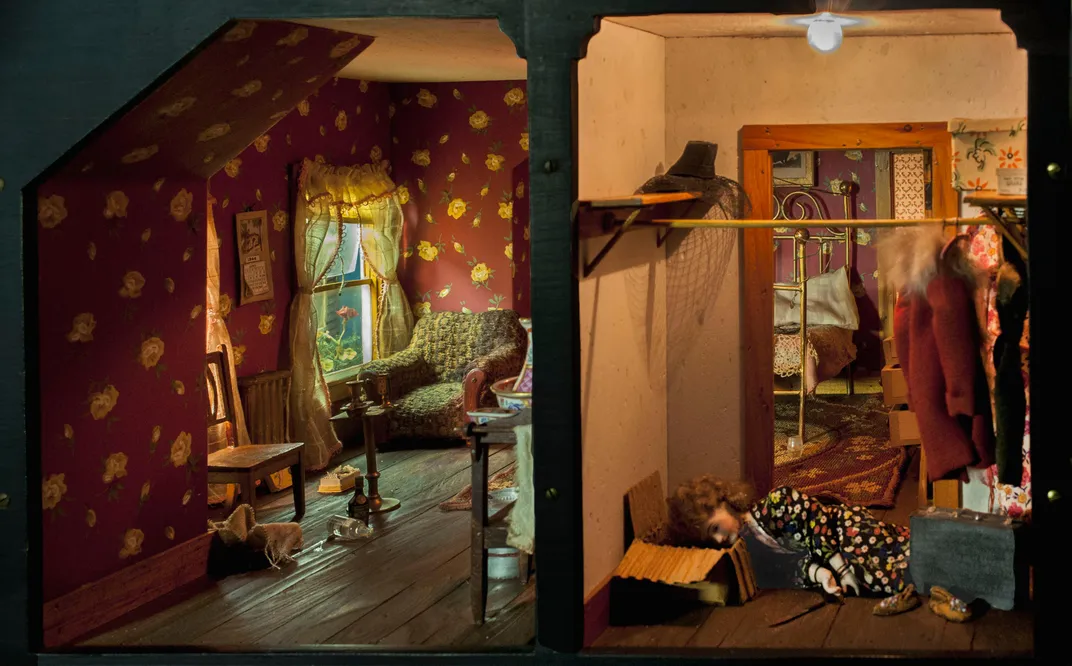

Lee created the Nutshells during the 1940s for the training of budding forensic investigators. Inspired by true-life crime files and a drive to capture the truth, Lee constructed domestic interiors populated by battered, blood-stained figures and decomposing bodies. The scenes are filled with intricate details, including miniature books, paintings and knick-knacks, but their verisimilitude is underpinned by a warning: everything is not as it seems.

“Murder Is Her Hobby,” an upcoming exhibition at the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s Renwick Gallery, examines the Nutshells as both craft and forensic science, challenging the idea that the scenes’ practicality negates their artistic merit, and vice versa. The show, which runs from October 20 to January 28, 2018, reunites 19 surviving dioramas and asks visitors to consider a range of topics from the fallibility of sight to femininity and social inequality.

Nora Atkinson, the Renwick’s curator of craft, was initially drawn to the Nutshells by their unusual subject matter. After conducting additional research, however, Atkinson recognized the subversive potential of Lee’s work.

“I started to become more and more fascinated by the fact that here was this woman who was using this craft, very traditional female craft, to break into a man's world,” she says, “and that was a really exciting thing I thought we could explore here, because these pieces have never been explored in an artistic context.”

Lee (1878-1962), an upper-class socialite who inherited her family’s millions at the beginning of the 1930s, discovered a passion for forensics through her brother’s friend, George Burgess Magrath. A future medical examiner and professor of pathology, Magrath inspired Lee to fund the nation’s first university department of legal medicine at Harvard and spurred her late-in-life contributions to the criminal investigation field.

Armed with her family fortune, an arsenal of case files, and crafting expertise, Lee created 20 Nutshells—a term that encapsulates her drive to “find truth in a nutshell.” The detailed scenes—which include a farmer hanging from a noose in his barn, a housewife sprawled on her kitchen floor, and a charred skeleton lying in a burned bed—proved to be challenging but effective tools for Harvard’s legal medicine students, who carefully identified both clues and red herrings during 90-minute training sessions.

“The point of [the Nutshells] is to go down that path of trying to figure out what the evidence is and why you believe that, and what you as an investigator would take back from that,” Atkinson explains. “It really is about learning how to approach your crime scene, learning how to see in that environment.”

Following the Harvard department’s 1967 dissolution, the dioramas were transferred to the Maryland Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, where they have been used as training tools ever since. An additional diorama, fondly referred to as the “lost Nutshell,” was rediscovered at the site of Lee’s former home in Bethlehem, New Hampshire, about a dozen years ago. The Renwick exhibition marks the first reunion of the surviving Nutshells.

Conservator Ariel O’Connor has spent the past year studying and stabilizing the Nutshells. Her job is to ensure the integrity of Lee’s original designs, whether that translates to object placement or material preservation. Just as Lee painstakingly crafted every detail of her dioramas, from the color of blood pools to window shades, O’Connor must identify and reverse small changes that have occurred over the decades.

“There are photographs from the 1950s that tell me these fixtures [were] changed later, or perhaps I see a faded tablecloth and the outline of something that used to be there,” O’Connor says. “That's the evidence I'll use to justify making a change. Everything else stays the same because you don't know what's a clue and what's not.”

Woodpiles are one of the most mundane yet elucidating details O’Connor has studied. During a visit to the Rocks Estate, Lee’s New Hampshire home, she noticed a stack of logs identical to a miniature version featured in one of the Nutshells. Both followed an exact formula: levels of three logs, with a smaller middle log and slightly taller ones on either end.

Comparatively, the woodpile in Lee’s “Barn” Nutshell is haphazardly stacked, with logs scattered in different directions. As O’Connor explains, the contrast between the two scenes was “an intentional material choice to show the difference in the homeowners and their attention to detail.”

Lighting has also been an integral aspect of the conservation process. According to Scott Rosenfeld, the museum's lighting designer, Lee used at least 17 different kinds of lightbulbs in the Nutshells. These incandescent bulbs generate excessive heat, however, and would damage the dioramas if used in a full-time exhibition setting.

Instead, Rosenfeld spearheaded efforts to replace the bulbs with modern LED lights—a daunting task given the unique nature of each Nutshell, as well as the need to replicate Lee’s original atmosphere. After nine months of work, including rewiring street signs in a saloon scene and cutting original bulbs in half with a diamond sawblade before rebuilding them by hand, Rosenfeld feels that he and his team have completely transitioned the tech while preserving what Lee created.

“Often her light is just beautiful,” Rosenfeld says. “There's light streaming in from the windows and there's little floor lamps with beautiful shades, but it depends on the socio-economic status of the people involved [in the crime scene]. Some are not well-off, and their environments really reflect that, maybe through a bare bulb hanging off the ceiling or a single lighting source. Everything, including the lighting, reflects the character of the people who inhabited these rooms.”

Lee’s inclusion of lower-class victims reflects the Nutshells’ subversive qualities, and, according to Atkinson, her unhappiness with domestic life. Although she had an idyllic upper-class childhood, Lee married lawyer Blewett Lee at 19 and was unable to pursue her passion for forensic investigation until late in life, when she divorced Lee and inherited the Glessner fortune.

“When you look at these pieces, almost all of them take place in the home,” Atkinson says. “This place that you normally would think of, particularly in the sphere of what a young woman ought to be dreaming about during that time period, this domestic life is suddenly a kind of dystopia. There's no safety in the home that you expect there to be. It's really reflective of the unease she had with the domestic role that she was given.”

Ultimately, the Nutshells and the Renwick exhibition draw viewers’ attention to the unexpected. Lee’s life contradicts the trajectory followed by most upper-class socialites, and her choice of a traditionally feminine medium clashes with the dioramas’ morose subject matter. The Nutshells’ blend of science and craft is evident in the conservation process (O’Connor likens her own work to a forensic investigation), and, finally, the scenes’ evocative realism, which underscores the need to examine evidence with a critical eye. The truth is in the details—or so the saying goes.

“Murder Is Her Hobby: Frances Glessner Lee and The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death” is on view at the Renwick Gallery from October 20, 2017 to January 28, 2018.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)