In the Home, a Woman’s Work Is Never Done, Never Honored and Never Paid For

Two historic firsts at the American History Museum; a woman steps into the director’s seat and a new show examines the drudgery of housework

:focal(685x557:686x558)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f2/fa/f2fa61f2-06e8-4516-b89d-d726cd8218aa/jn2019-00080.jpg)

As the nation celebrates Women’s History Month in the midst of the #MeToo movement, and international conversations are underway about everything from sexual violence to pay equity for women, it seems particularly apropos the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History named for the first time in its 55-year history a female director.

“There’s nothing like the Smithsonian,” gushes Anthea Hartig, the Elizabeth MacMillan director, who was born the year the museum opened. “I’m so incredibly thrilled and honored and humbled and excited.” Most recently Hartig was the executive director and CEO of the California Historical Society. There, she raised more than $20 million, quadrupled the annual budget, launched the digital library and oversaw the production of more than 20 exhibitions. Hartig also created partnerships with more than 250 organizations including the city and county of San Francisco and the LA Plaza de Cultura y Artes in Los Angeles. But this new job, she says, is really cool!

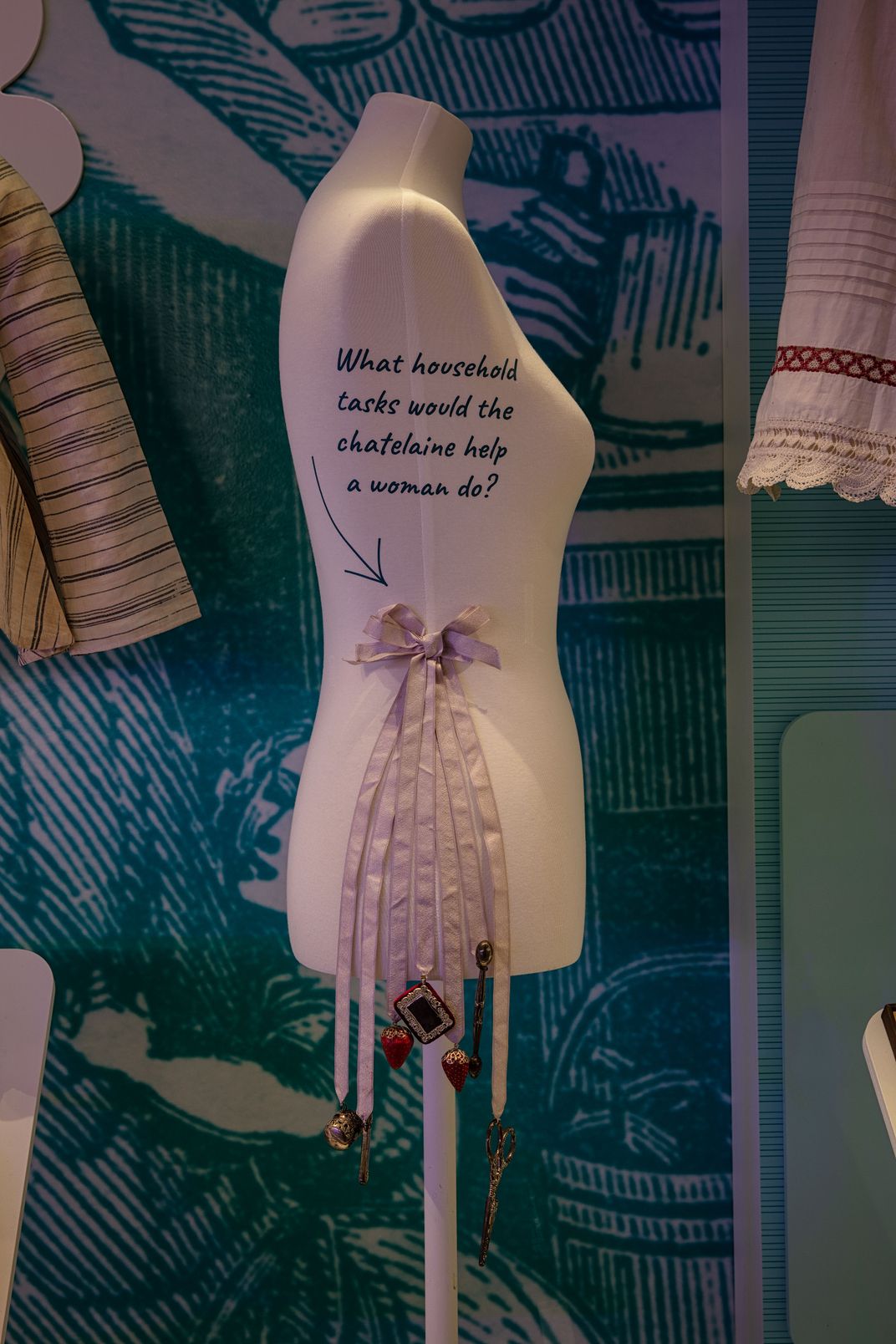

Hartig was just at the opening of museum’s new exhibition, “All Work, No Pay: A History of Women’s Invisible Labor,” which takes a look at the implied expectation that women will always take care of the housework. The case display also examines the fact that despite advances in the paid labor force since the 1890s up through 2013, women are still doing most of the unpaid work at home. There’s a graphic showing that according to the 2013 U.S. Census, women on average earn 80 cents for every dollar that men make. It also displays a range of clothing and accessories worn and used by women in the home as they clean and care for their families, and points out that for African-Americans, Latinas and other women of color, expectations are even higher and harder to bear. Hartig says the exhibition focuses on the invisibility of a lot of domestic work throughout all of American history.

Gender, Hartig notes, does matter to people, and this way, one can have a conversation. “About how are you a working mother? How did that work? How have women worked all throughout time? What did it take us? What did it take our foremothers and forefathers and especially our foremothers? What kind of sacrifice—what kind of advocacy and effort? What kind of courage did it take for them to get the rights that I now enjoy and that we still have to defend,” Hartig muses.

Hartig is a bit of a renaissance woman as well as a historian, author and city planner who is dedicated to making history accessible and relevant. She’s a lover of culture with a wide range of interests—cooking, tennis, reading and hiking, among them. With a full plate at the Smithsonian, overseeing 262 employees as well as a budget of nearly $50 million, plus being tasked with opening three major exhibitions this year and next as part of the Smithsonian’s American Women’s History Initiative, one might wonder whether Hartig feels extra pressure as the first women to lead the American History Museum.

“I’m taking it as I was the best qualified candidate. That I was a woman I think is incredibly important in these times. . . . It’s a really nice story that I’ve spent my entire career as a public historian either in archives, or heritage conservation, or in teaching or with history museums and historical societies, and that I am a woman I think positions me very well,” says Hartig, who’s been everything from a municipal preservation planner to an assistant professor in the department of history, politics and sociology at La Sierra University in Riverside, California.

“I’ve been a working mother. I finished my PhD working full time with two babies, and so I was lucky that I was cushioned by my class, and my race, and my family, and my husband. But I am also a very diligent person,” Hartig explains. “I get a lot of those kind of questions and I love them. . . . I don’t take it as a sexist question. I think it is a gendered question because if it didn’t matter you wouldn’t be asking.”

In the new show, clothing that is tailored to the purposes of sewing, doing laundry, ironing, cleaning, cooking and child care is the backdrop of a timeline stretching from the 1700s to the 1990s. Short gowns worn in the 1700s and early 1800s allowed a greater freedom of movement and were sometimes adorned with pockets tied on like aprons to hold thimbles and scissors. Later in the 20th century clothing executive Nell Donnelly Reed designed her stylishly fitted Nelly Don dress in bright cheerful colors and patterns.

“I think these are really brilliant choices to use some of our clothing collection as a way to illustrate those invisibilities, and there’s nothing like a museum exhibition to make them visible,” Hartig says. “This petite but powerful show, I think, also helps us understand the pivotal intersections of our gender of course, but really our race, our class and our ethnicity in terms of which women work.”

Co-curator Kathleen Franz says the museum wanted to specifically acknowledge the struggles of women of color including African-Americans who worked as slaves, and black, Latina and Asian women who worked as domestics. Those women had to take care of their families at home as well.

“Black women, Asian women and Latinos are at the lower end of the wage scale, and we have a nice quote in this exhibition from (activist) Angela Davis because she is really part of the debates in the 1960s and 70s to value women’s work. What she points out is, that black women are like Sisyphus. They’ve labored in a double invisibility in the home working in other people’s homes and working in their own homes and their wages are the lowest,” says Franz. “So, we really wanted to pull that out as well so that people see that women are not all the same.”

Some of the artifacts in “All Work, No Pay” come from the many women who worked at the American History Museum over decades, says Franz, who collected aprons and other items that have never been in an exhibition until now. One of her favorite pieces is an intricately embroidered apron from around 1880 or 1890. It includes a needle case, and a poem that reads: “Needles and pins, needles and pins, when we get married our trouble begins.”

“It was probably a wedding gift. . . .It’s a really funny, ironic piece on an apron. You can see that it might have been given in a sense of irony,” Franz says, pointing out the level of labor that went into making it. “It’s a man proposing and giving a woman flowers. She’s casting down the flowers to the ground and he’s shocked. It’s a nice piece because the women’s suffrage movement was well underway in the late 19th century when this was made.”

Co-curator Kate Haulman, an associate professor of history at American University, has some thoughts on what she hopes the takeaway from this exhibition would be. What would a suited, female business executive think?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/11/cc/11ccf7be-e3ac-4bdc-9bbd-8874a2adb3cc/jn2019-00071.jpg)

“This is somebody who . . . probably outsources much of this labor that goes on in her own home, and that work is typically low paid, so (the exhibition) might bring that to greater consciousness,” Haulman says. “I would also say that because of the ceaseless nature of these tasks, even if you have somebody coming in and helping for pay, you’re probably doing some of this yourself.”

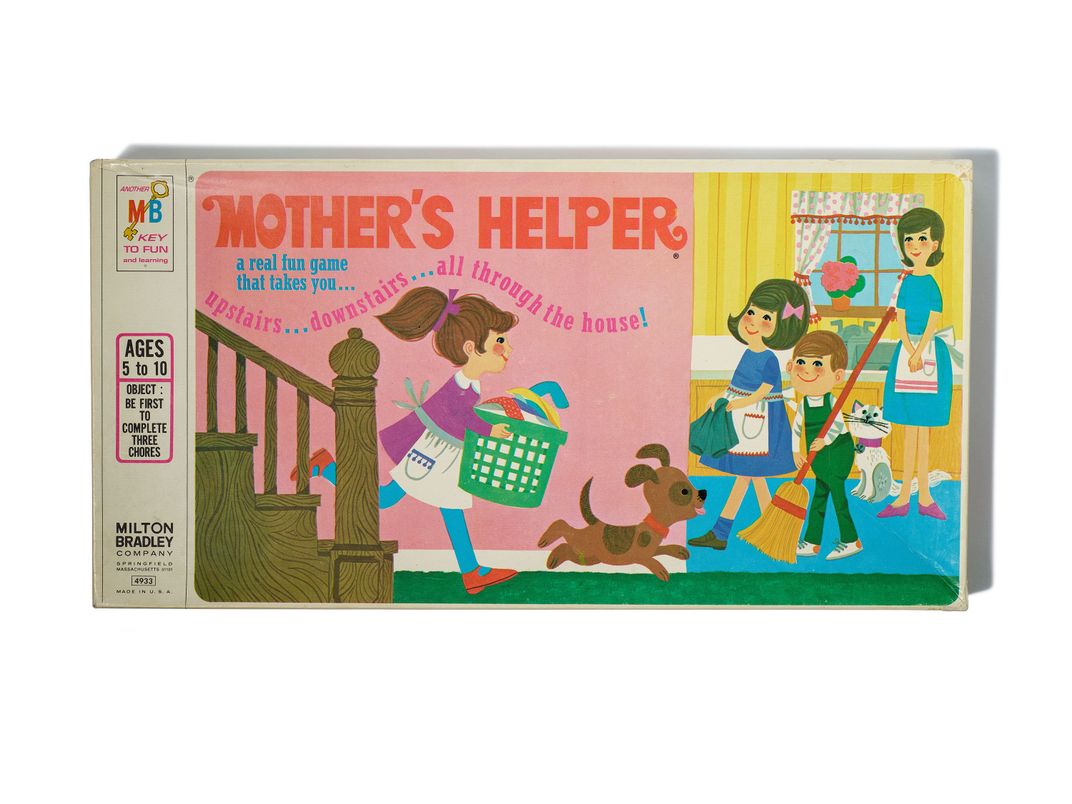

Haulman hopes this exhibition would also resonate with men, or with any partnered household where there are conversations about equity in the home. She also thinks part of the reason the whole thing was mounted was to turn women’s work on its head.

“Usually when we say work often people think paid work—wages, paychecks, salaries, but so much of work today and across American history has not been paid,” she explains, “so we wanted to highlight that this is true of much work. It is certainly true for the work of domestic spaces and the work of care and that work, historically, has been done by women.”

Director Hartig says part of her vision for this museum is to continue to expand access so that people feel comfortable and making sure that history is presented in ways in which people see themselves reflected. History, she notes, is happening right now. “It’s an incredibly exciting time to think about making history accessible especially as we move toward the centennial of women’s suffrage, but also as we think about the 250th birthday of the nation in 2026,” Hartig says. “There’s been a terribly powerful and incredibly difficult experiment in how to create a new nation. I want to believe that there’s a lot more that we have in common than that which separates us, and I think history can be a remarkable tool for locating those places where we are more alike.”

“All Work, No Pay,” curated by Kathleen Franz and Kate Haulman, is now on view at the National Museum of American History as an ongoing display in the museum's first floor center grand foyer. The exhibit is part of the Smithsonian American Women's History Initiative.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)