This Homemade Flag From the ‘70s Signals the Beginning of the Environmental Movement

The green-and-white banner from an Illinois high school recalls the first Earth Day 50 years ago

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/65/1e/651ee24b-5e26-41b2-86d3-59646f43f9b0/apr2020_h05_prologue.jpg)

Early in 1970 at Lanphier High School in Springfield, Illinois, Raymond Bruzan turned his class, Room 308, into the “Environmental Action Center,” as a sign on the door announced. Now it was a place where the 24-year-old biology teacher and his students could debate what they could do to protest the nation’s polluted air and water on the first Earth Day, scheduled for April 22.

The young activists decided to stage a mock funeral procession in their school for the “dead” Earth that awaited them if Americans didn’t stop poisoning the environment. With a mix of mischief and solemnity, they walked the halls bearing a casket that held a plastic skeleton on loan from the biology storeroom. Then Bruzan and 60 or 70 students set out for the Illinois State Capitol, two miles away, where they would present the lieutenant governor with antipollution petitions signed by more than 1,000 people.

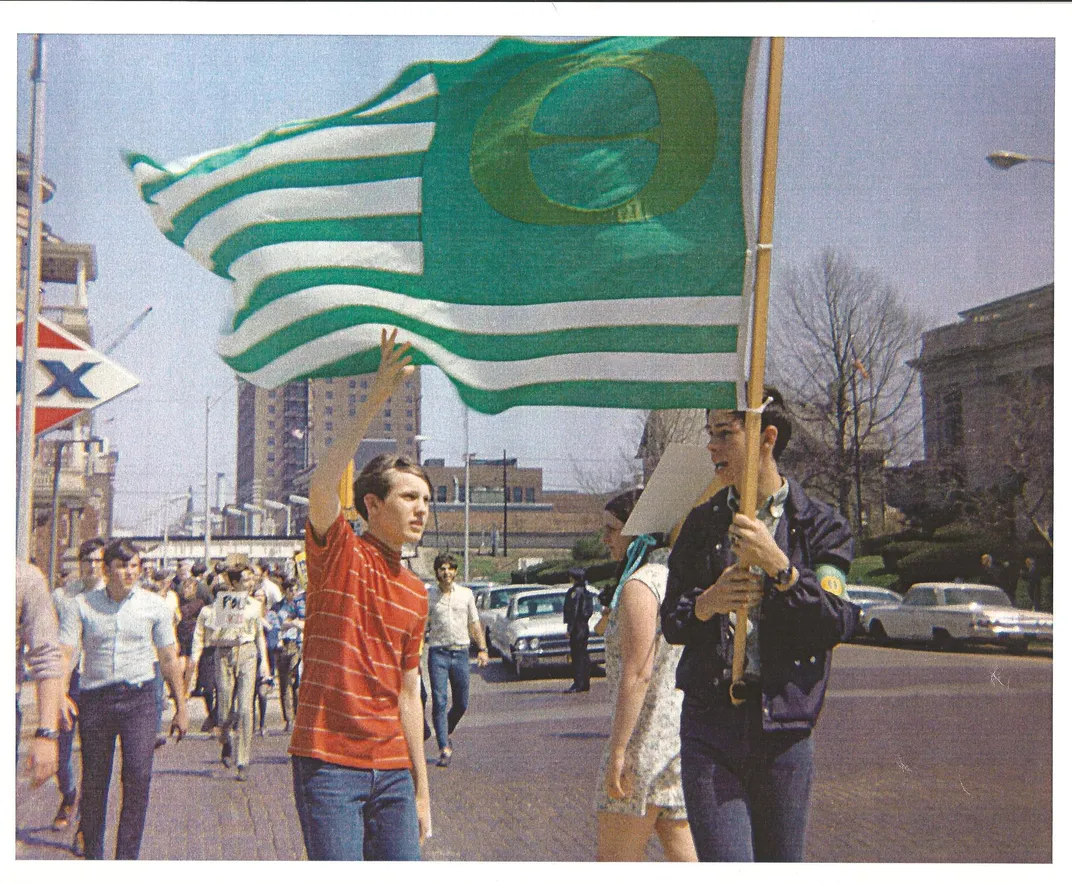

Bruzan, wearing a white dress shirt and a rep tie, had arranged a police escort for the protest marchers, who carried signs that offered plaintive pleas and clever jibes: “Save Our Lakes.” “The End Could Be Near.” “Isn’t It Nice to Get Up in the Morning and Hear the Birds Cough?” A few students wore armbands with the newly designed ecology symbol, an “e” superimposed on an “o” to express the dependence of all organisms on their environment. And one student raised a green flag with white stripes bearing the same symbol. Today the flag is an artifact of a pivotal moment in America’s environmental consciousness.

Bruzan recalls that the mother of one of his students sewed the 3- by 5-foot flag. The ecology symbol had been created in October 1969 by the cartoonist Ron Cobb of the Los Angeles Free Press, an alternative newspaper. The symbol, intended for protesters to rally around, also appeared in his 1970 collection Raw Sewage.

The homemade green-and-white flag in Springfield showed that the environmental cause had broad appeal. Lanphier High was in a working-class part of the city, the North End. According to a 2014 history of the school, North Enders were “the salt of the earth,” and among the clubs that high-school girls could join were those for future secretaries, nurses, teachers and homemakers. It was common for boys to go on to trade schools.

One of the reasons that the first Earth Day changed history was that, like the hand-sewn flag, it was do-it-yourself. In September 1969, Senator Gaylord Nelson of Wisconsin vowed to organize “a nationwide teach-in on the environment,” but did not insist on a specific format, instead encouraging local organizers to shape their own events. As a result, the teach-in became something much bigger than Nelson had imagined, inspiring and uniting people of varying lifestyles and ideologies. Roughly 10,000 schools, 1,500 colleges and universities and hundreds of communities held Earth Day celebrations. Millions took part.

At Lanphier, the school’s Earth Day protest lifted the spirits of senior Georgene Curry. Writing in the student newspaper, she confessed that she feared pollution would soon turn the song “America the Beautiful” into a pathetic joke. But Earth Day had given her hope. “Lanphier students, under the direction of Mr. Bruzan, have already taken a step forward,” she wrote. “The petition-passing and the march to the capitol building made the public aware of the problem, if the public had been blind enough not to notice it before Earth Day.”

Nationally, the mass demonstration of concern led to a series of landmark environmental laws, beginning with the Clean Air Act of 1970. Earth Day also built a political and educational infrastructure that still bolsters the movement today: lobbying groups, environmental reporters, college environmental-studies programs.

Though Bruzan never led another protest march, each year he hung the ecology flag in his classroom on April 22—until 1994, when he gave it to the Smithsonian, six years before he retired from Lanphier. In Bruzan’s view, the flag represented not the political fringe but the nation’s can-do spirit: If we could put someone on the Moon, he thought, we should be able to restore our environment. “Now I know it’s not that simple,” he says. “But I remain hopeful.”