How the 19th Amendment Complicated the Status and Role of Women in Hawai’i

For generations, women played a central role in government and leadership. Then, the United States came along

:focal(815x198:816x199)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c8/c3/c8c304d9-627e-4069-bd51-176c91234641/npg-npg_80_320.jpg)

When the 19th Amendment was finally ratified on August 18, 1920, some women in Hawaiʻi wasted no time in submitting their names to fill seats in government. But, as Healoha Johnston, curator of women’s cultural history at the Smithsonian’s Asian Pacific American Center (APAC), explains, these women didn’t realize that the right to vote didn’t automatically guarantee that women could also hold office.

Their confusion was understandable. After all, women in Hawaiʻi had held key positions in government for generations. Before the U.S. annexed it as a territory in 1898, Hawaiʻi had been an independent country with a constitutional monarchy. Women were ambassadors, judges on the supreme court, governors and monarchs.

“That’s where their minds were,” says Johnston. “They were already ten steps ahead of the vote. They were absolutely ready to occupy those positions.” As it turned out, it took five more years and an amendment for Rosalie Enos Lyons Keliʻinoi (1875-1952) to be elected and become the first woman to hold office in the Hawaiian Territorial Legislature.

As host Lizzie Peabody explains in the most recent episode of Sidedoor, a Smithsonian Institution podcast, the achievement of the 19th Amendment in Hawai'i was a complicated and confusing win. “We tend to think of the 19th Amendment as the moment women gained power in America. But in fact, it was a moment when some women—Hawaiian women—regained a small portion of the power they once held,” Peabody notes.

On Sidedoor, learn how women’s suffrage came to Hawai‘i

For the people of the U.S. territories Guam, the Philippines, Puerto Rico and Hawaiʻi, the fight for votes for women was closely connected to the fight for territorial independence. Even though women could vote in territorial elections, citizens of U.S. territories could not vote in presidential elections. (Hawaiians, men and women, were only able to vote in presidential elections when the territory became the 50th state in 1959.)

The long history of Hawaiian women in government can be traced back to the traditional Hawaiian conceptions of power, says Kālewa Correa, APAC’s curator of Hawaiʻi and the Pacific. Native Hawaiians understand that mana—spiritual energy, which can be gained and lost by a person over time—could only be traced through one’s mother. “Historically, women held an immense amount of power,” Correa explains.

With James Cook’s arrival to the islands in 1778, European contact ushered in an era of deadly disease, marking a period of intense crisis for Native Hawaiians. By some estimates, up to 95 percent of native Hawaiians died in the half-century following Cook’s arrival, Correa says.

Hawaiians responded by creating a constitutional monarchy, intent on preserving their native culture and sovereignty. By 1890, the country had more than 80 embassies worldwide. “As an independent country, we’re going around the world and creating diplomatic relationships with other countries,” Correa says. “And women played an integral part in all of that.”

Queen Emma of Hawai‘i visited President Andrew Johnson’s White House in 1866 to promote Hawaiʻi as an independent nation. In 1887, Queen Kapi‘olani was on her way back to Hawaiʻi from a trip to Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee when she stopped by the United States National Museum (now the Smithsonian) in Washington D.C. There, she donated a waʻa, or canoe, “as a gift between two nations,” emphasizes Correa. “That demonstrates the kind of power she had,” he says.

Queen Liliʻuokalani was elected in 1891 as the first and only queen regnant of the Hawaiian Kingdom and shepherded the country through a period of intense growth. But her rule was cut short in 1893, when five white American and European businessmen—mostly foreigners who had made their fortune on Hawaiian sugar plantations—overthrew Liliʻuokalani in a coup d’état and established a provisional government.

As Johnston explains, these new rulers strategically barred women from voting, in part to curtail the power of the Native vote. Native Hawaiians and other women of color formed a large portion of the population still loyal to the Hawaiian monarchy—and therefore posed a serious threat to this new system, in the eyes of the white rulers. As Johnston tells Peabody, the colonialists and U.S. forces argued, through racist logic, that Native Hawaiians were incapable of self-rule.

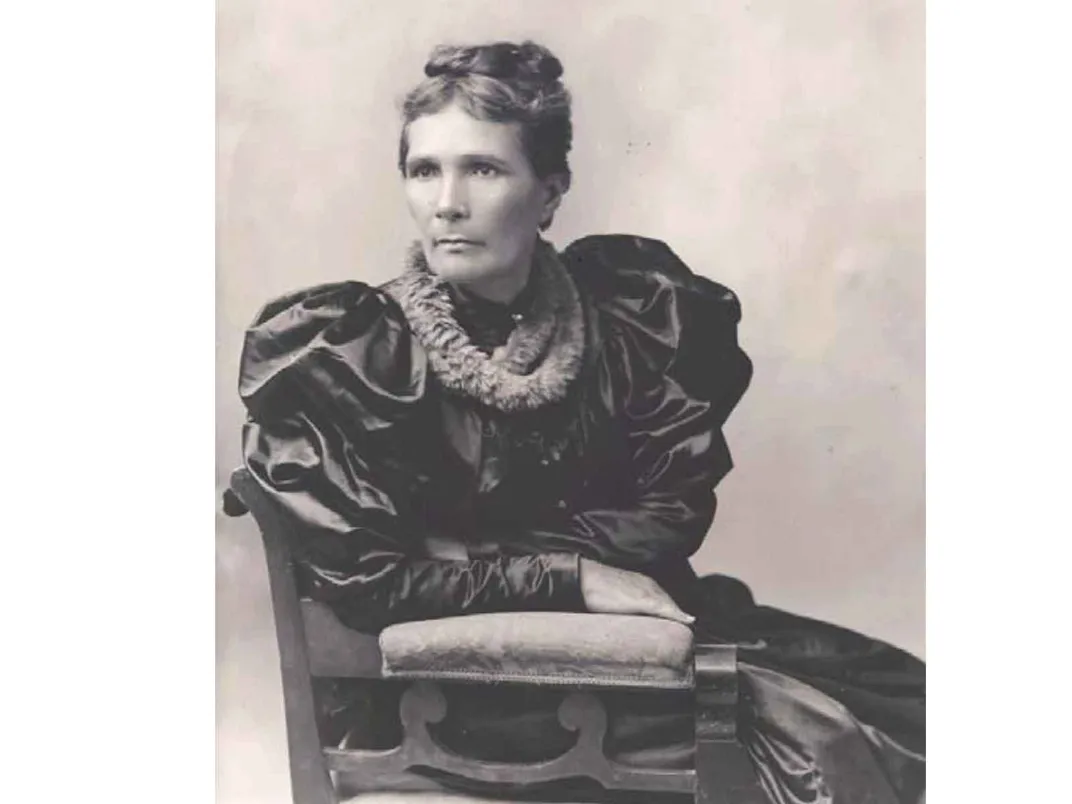

For some women living through this upheaval, such as Judge Emma Nakuina, this new system created an ironic paradox, Peabody points out. Nakuina was a prominent Hawaiian judge, but could no longer vote on territorial matters.

Shortly after the overthrow, Nakuina and her protegee Wilhelmina Dowsett began organizing for women’s right to vote on the islands. Dowsett, the daughter of a German immigrant and a Native Hawaiian woman with royal ancestry, spearheaded the fight for suffrage in Hawaiʻi. As a member of a wealthy family with ties to high society, Dowsett leveraged her connections to create the National Women’s Equal Suffrage Association of Hawaiʻi in 1912.

In the following decade, Dowsett and a multi-ethnic coalition of Hawaiian women organized speeches in churches, created petitions and held rallies. They wrote countless columns in Hawaiian newspapers, which circulated around the islands and became a key space for communicating about the suffrage debate, Johnston says.

When the 19th Amendment finally passed, it was in part thanks to the tireless organizing of these Hawaiian women. Yet Dowsett and others knew that suffrage was just the beginning. Johnston points to one newspaper clipping as a small, but poignant example—a letter to the editor in The Garden Island, dated to August 24, 1920 and titled, with the hint of a threat, “The Chance to Get Even.”

In it, the letter-writer encourages women to wield their now-regained political power wisely. “When the women of Kauai get the vote and come to the polls for the next election, they will doubtless recall how relentlessly some of the members of the last legislature fought the [women’s] suffrage bill,” they write. “…[T]hese obstructionists were warned that the day would come when the women would get back at them. […] That time has come, and some of these same men are now in the field looking for votes. Now is the time to remember them!”

This clipping stands out to Johnston, in part because “it has this very determined and self-possessed voice,” she says. It’s a good example of the attitude that many Hawaiian women took to the fight for suffrage. “They realized [the vote] was a point of entry into a larger political structure. And they were very savvy about all of it, because they had existed within the political structure before,” Johnston says.

These women saw suffrage as one key part of a larger fight—for Hawaiian independence, and the ability of women to participate in their home’s future. “This was a way to have a voice again in determining Hawaiʻi’s future, and determining the rights of the people. […] There’s this recognition that, political power will come after the vote,” Johnston says. “This is just step one.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)