How the 2016 MacArthur Genius Award Recipient Lauren Redniss Is Rethinking Biography

The visual biographer of Marie and Pierre Curie turns to her next subject, weather, lightning and climate change

Biography is one of the oldest forms of history. It serves a public function. Biography aims to record and commemorate—even celebrate—exemplary lives. In Renaissance Italy, biography was an adjunct to portrait painting as a way of recognition. Biography is a way of linking private with public lives. It shows how character develops in childhood and then reveals itself to the public as the individual steps into the world as an adult. Biography is constantly reinventing itself, adding dimension, depths and new approaches to the lives of emblematic people in past time.

At the National Portrait Gallery’s recently created Center for Visual Biography we are exploring new innovative approaches to telling lives and to support scholarship about portrait biography.

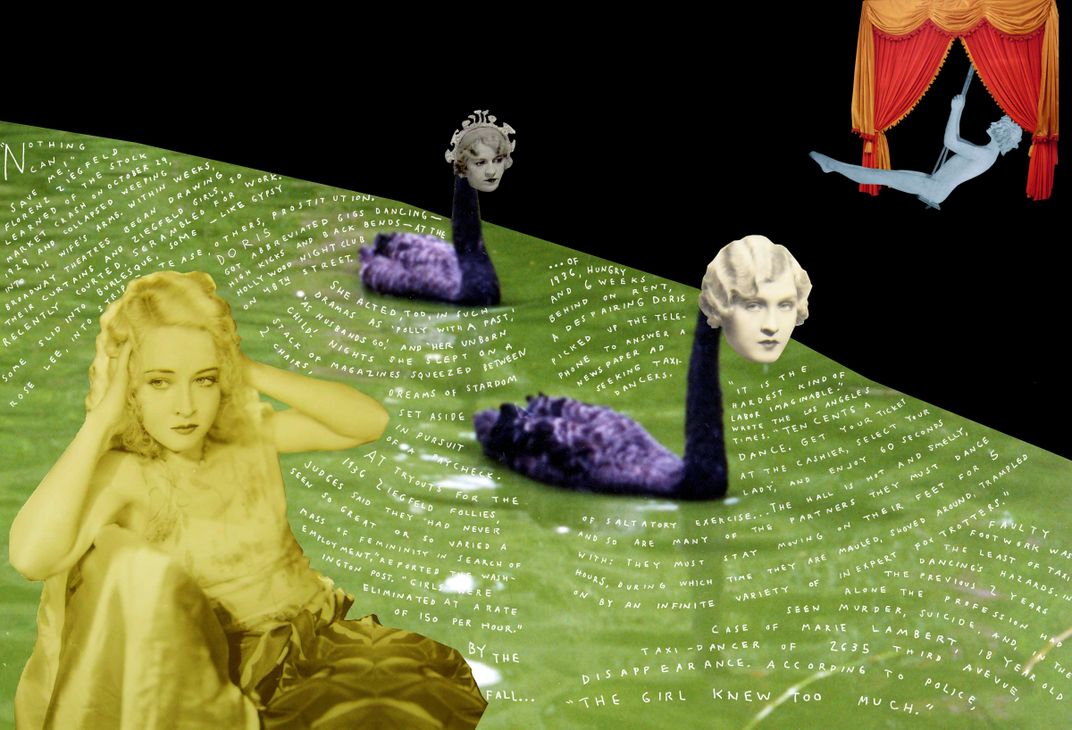

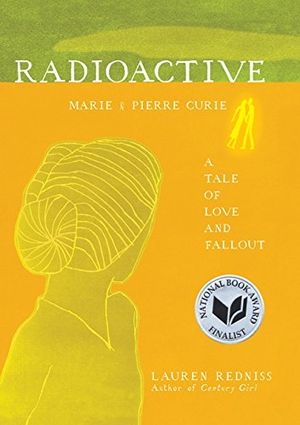

Artist and writer Lauren Redniss is among our advisors. Her visual biographies about the scientists Marie and Pierre Curie and Ziegfeld showgirl Doris Eaton Travis (who lived to be 106) are a delight to the eye, but also show a new way of revealing the contours and dimensions of past lives.

Redniss takes an oblique approach, finding meanings in the scraps and details of the lives of her subjects—postcards, snapshots, diary entries and shopping lists as well as other physical evidence. She is not interested in master narratives but idiosyncratic ways to visually enter the worlds of the people who interest her. Above all, she is fascinated with people who are survivors, people who endure and overcome.

For her imaginative engagement with past lives as well as the world around us, Redniss was recently awarded a MacArthur Grant, and while, in her modesty, she would eschew the label of genius, her work is an influential indicator toward new directions in visual biography.

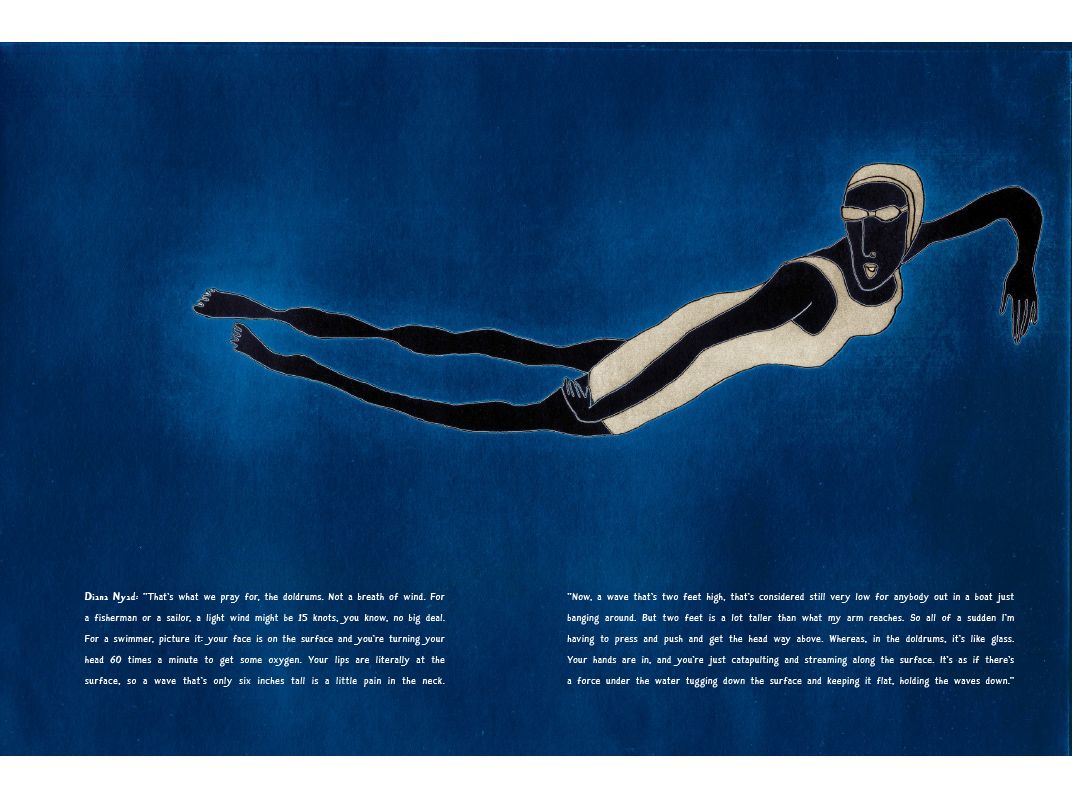

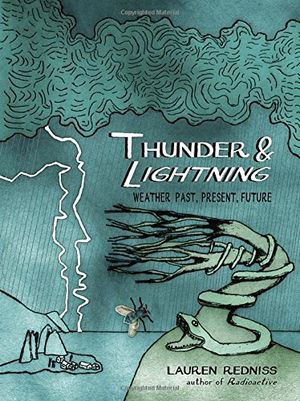

In her new book, the acclaimed Thunder & Lightning: Weather, Past, Present and Future, she is intrigued by how people have coped with, survived, or failed in extreme weather situations. In the context of concern about global climate change, Redniss’ take on the history of weather is entertaining, but also salutary in what it tells us about human vulnerability to changes in the atmospheric membrane which supports life on earth.

We sat down recently for a discussion of her works and her process.

Tell me why you are interested biographically in people who overcome, who keep working against the odds and against various obstacles.

I think I am drawn to people who are undaunted by hardship. It puts things in perspective. I don’t usually think of my work as therapeutic, but in this case, it probably is. Doris Eaton survived heartbreak, economic peril, the murder of a sister, the death of five other siblings and her spouse, just for starters. Marie Curie was up against a patriarchal system loathe to acknowledge or reward her scientific research, working tirelessly with toxic substances that were slowly killing her. And she still managed to be a tremendous teacher, humanitarian and mother. Wait, what was I complaining about again?

Did you have other plans or dreams as a kid? Did you start out as an artist?

As a kid I would stay with my grandparents in Worcester, Massachusetts, and work the cash register at my grandfather’s grocery store. On slow days I made signs and “jewelry” for the customers out of rubber bands and garbage ties. I always made things as a kid—shoes, little wooden carvings of animals, playing cards. Doing things with my hands was automatic, like it is for a lot of kids. My career is partly based on the fact that I never passed out of this phase. At various points I’ve had other aspirations: for a while I studied to be a botanist and worked in a plant research lab. I drew fossil turtles at the American Museum of Natural History.

How did words become part of your visual work?

Both my maternal grandparents could really spin a yarn. My grandfather was a private in Europe during World War II. At 20, he had never left Worcester, and suddenly there he was in Paris, in Alsace, in little towns in Italy, where a young girl poured him water from a glass pitcher with a streak of blue glaze— “a beautiful blue streak, deep blue, like the ocean,” where a blind woman gave him tomatoes, where he had to hustle to grab a mattress stuffed with sufficient straw to be able to sleep. At one point he was shot and left for dead in the forest. My grandmother worked in her father’s bakery, making jelly donuts and busting the milkman for drinking their cream. She remembered her town’s ghost stories. When I was in college, I started making tape recordings of these conversations. I had a sense that if I didn’t, their stories would be lost. This created a habit of interviewing people and recording oral histories. When I draw someone, the portrait seems incomplete without including their words, their voice. That’s how text crept into my work.

When did you think about doing art books?

I used to draw and write “Op-Arts” for the New York Times Op Ed page. These were single-panel narratives that looked at issues in the news in unexpected ways. I loved doing these, but the turnaround time was tight, and space that any piece could occupy was limited. I often felt that the most interesting parts of a story were getting cut. I wanted a more expansive canvas, so I started working on books.

Do you have another practice where you just do images or write?

I often draw, paint, or make collages with no eye toward publication. I have ideas for future projects that are either just images or just writing, but who knows. I have some ideas for work that is a complete left turn from what I’ve been doing.

I see a little Edward Gorey in your drawings. And then there is the pastiche of mixed media element in the book on Doris Eaton. Did you have any particular artistic influences?

I’m usually drawn to work that was, at least originally, created for something other than a museum or gallery. I’m interested in medieval religious painting, and scrimshaw, film stills, and paper ephemera like cigarette cards or mid-century Japanese matchbooks. I’m drawn to the narrative power of these kinds of work, and also what is sometimes a raw or even awkward quality.

Could you speak a bit about how you get interested in a topic and the process by which you start to conceptualize it as something you want to work on?

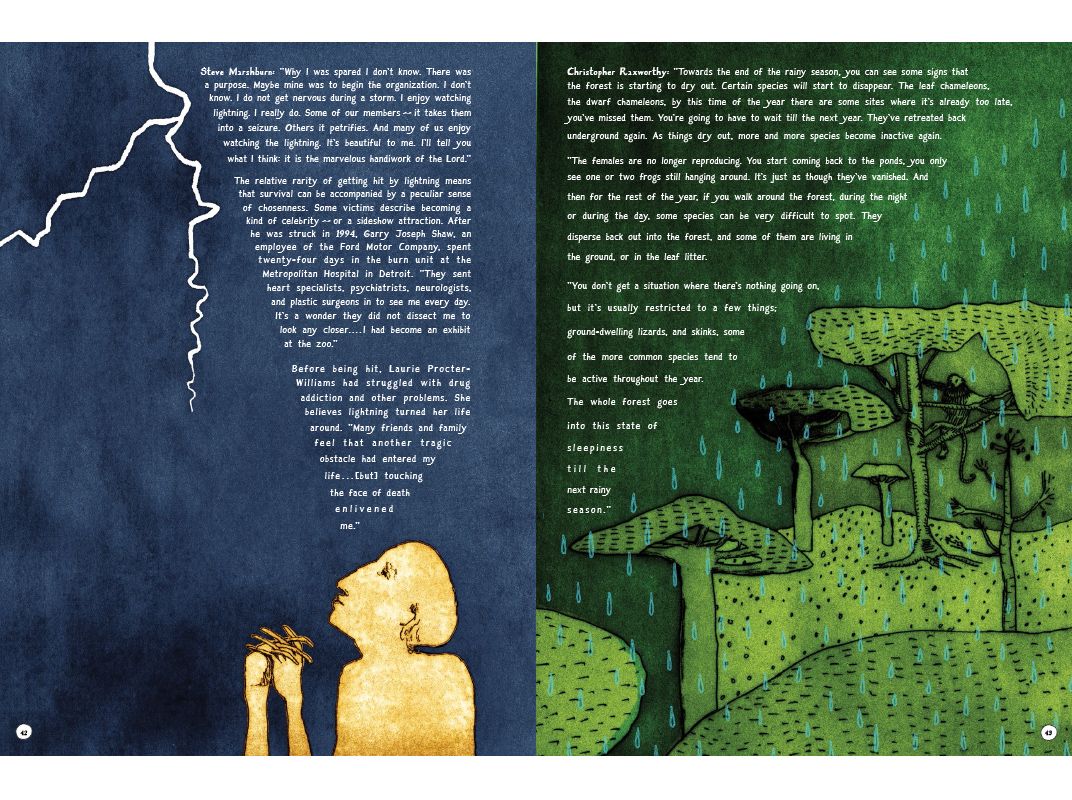

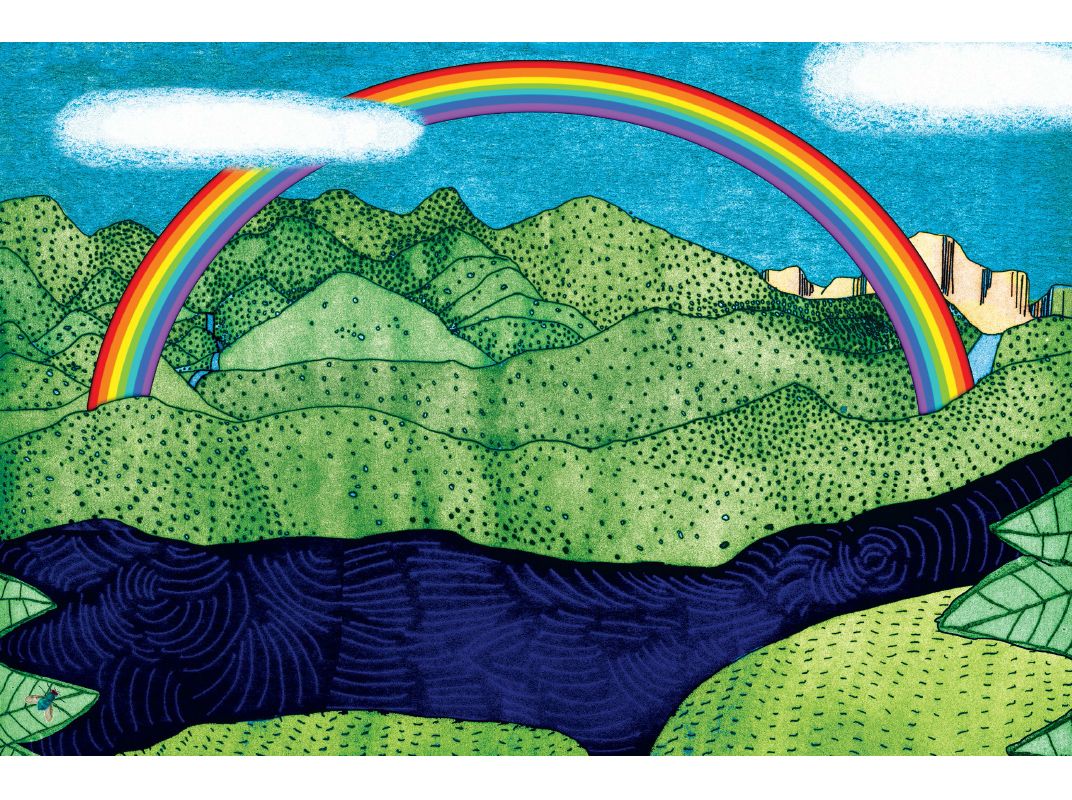

Whenever I am working a project, I begin to be haunted by some element that the project is missing. It could be aesthetic, a way of making the images or of using color, say. Or it could be conceptual, a question of subject matter. That missing element often becomes the seed of new work. Once I embark on a project, I’m reading, traveling, conducting interviews, drawing, taking photos, looking into archives. Certain themes begin to emerge. I create a “dummy book”: I bind a blank book and begin to collage in Xeroxes of my sketches. I print out sections of text and Scotch tape then to the pages. That way I can turn the pages and get a feel for the pacing and the book’s rhythms. The element of surprise is built into the form of a book: you don’t know what will be revealed when you turn a page. I have a chapter in my recent book called “Rain.” There are pages of rainy scenes, thunderstorms, and dark skies punctured by lightning bolts, descriptions of violent cyclones during Madagascar’s rainy season and interviews with lightning strike victims. Finally, the rain stops, you turn the page and, on a wordless spread, a brilliant rainbow arcs across the landscape. The drama of that image is created by its contrast to the preceding pages.

Marie Curie is such a Promethean story: she does all this incredible work and then dies from it. What drew you to the Curies, particularly Marie?

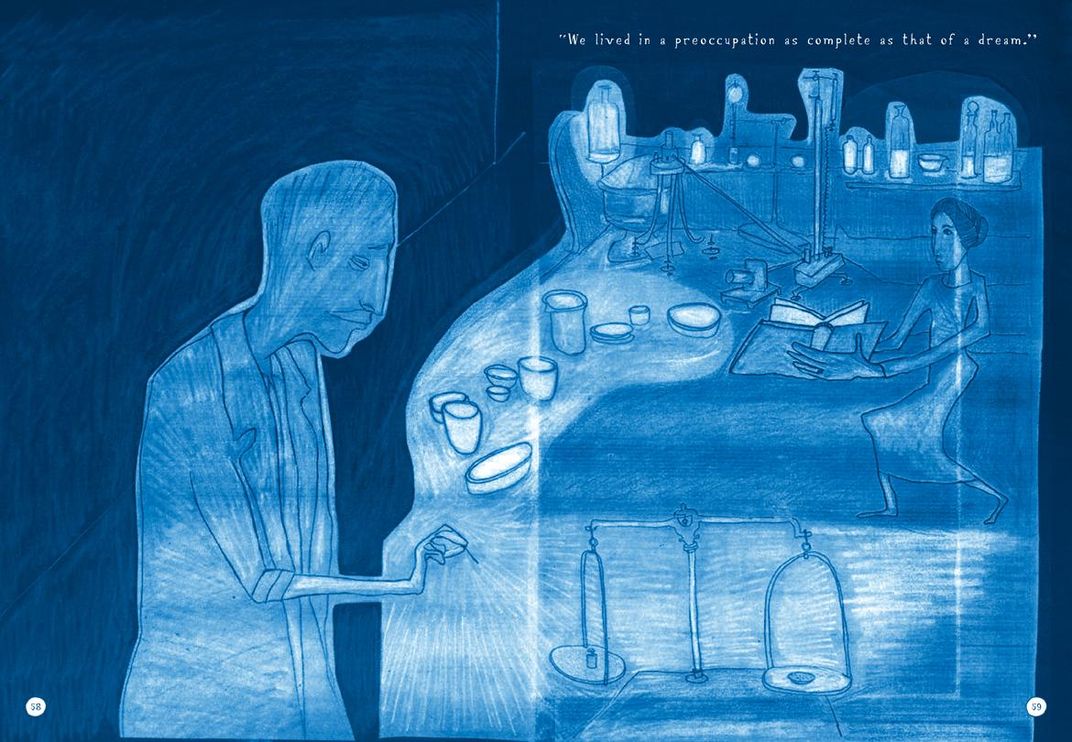

I liked the idea of creating a visual book about invisible forces. The Curies lives were animated by two invisible forces: radioactivity, a subject of their research, and love. They lived a great, and ultimately tragic, romance.

The weather, of course, is interesting because it is both serious and whimsical at the same time. Your drawings seemed to reflect that: you’re establishing a mood in a way. Is that fair?

Weather is, as you say, unpredictable. In a world where we’ve come to expect a high degree of control over our daily lives, there remains this fundamental uncertainty. That fascinates me. A storm, like a wild animal, can be simultaneously beautiful and terrifying.

I wanted Thunder & Lightning to be a beautiful object, a pleasure to hold and to read. I wanted to convey the many sensual experiences of weather—the disorientation of being lost in the fog, the uncanny stillness and quiet after a snowstorm, the unbeatable pleasure of a sunny day. But I wanted to face the terror, too. In the book, I also look at weather throughout history: as a force that has shaped religious belief, economics, warfare. Ultimately, Thunder & Lightning is my stealth climate change book. I’m worried about our planet.

Were you scared of lightning before writing the book? It freaks me out, as you know, now having read it.

I love lightning! At least, as long as I’m indoors. Maybe it’s because I don’t golf.

What are you working on now?

I’m working on a book about an Apache tribe in Arizona. I’m depicting three generations of one Apache family.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/39/d6/39d629bd-fc86-49a4-833d-353b7650f45c/redniss_2016_hi-res-download_4.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/David_Ward_NPG1605.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/David_Ward_NPG1605.jpg)