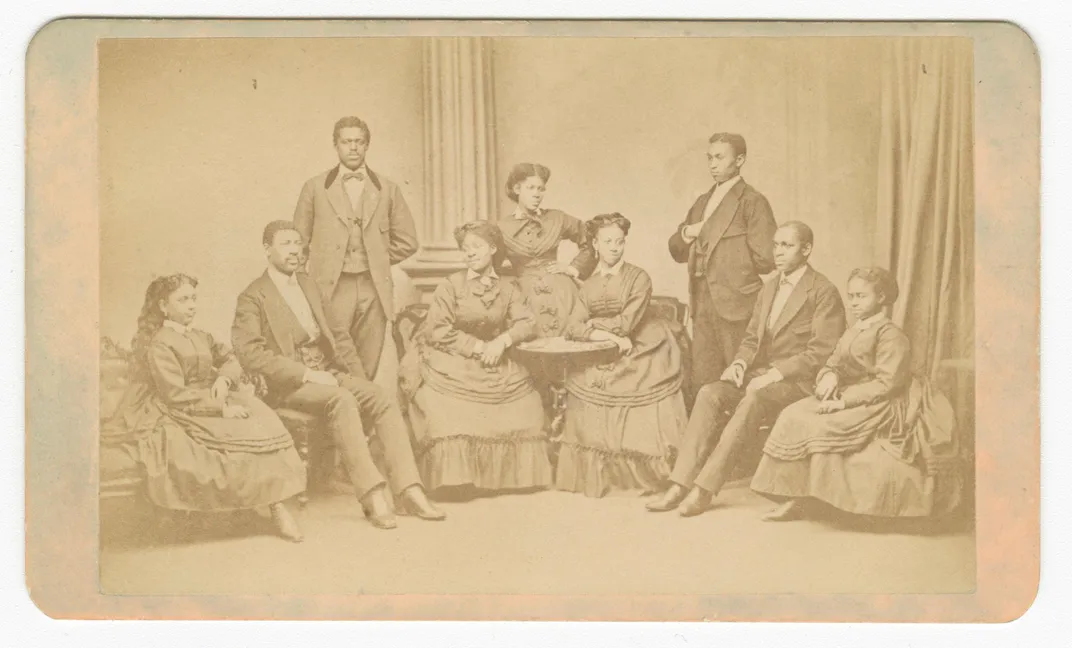

Inside a national period of tumult, at the crux of post-Civil War reconstruction of Black life in America, Sarah Jane Woodson Early became a historymaker. She’d already been among the first Black women in the country to earn a bachelor’s degree when she graduated from Oberlin College, one of the few institutions willing to educate non-white, non-male students. And when Wilberforce College in Ohio—the first historically Black college and university (HBCU) founded by African American people—hired Early in 1858 to lead English and Latin classes for its 200 students, she became the first Black woman college instructor and the first Black person to teach at an HBCU.

Each of the 101 HBCUs across 19 states carries its own legacy of brilliant Black women who cultivated triumphant careers, sometimes whole movements, as leaders in classrooms, on staffs and in administrations. Early is one of them.

So is Lillian E. Fishburne, a graduate of Lincoln University and the first Black woman promoted to rear admiral in the U.S. Navy. And Tuskegee University alum Marilyn Mosby, the youngest chief prosecutor of any major U.S. city. And entrepreneur Janice Bryant Howroyd, the first Black woman to run a billion-dollar business, who earned her undergrad degree at North Carolina A&T State University, the largest HBCU. And newly inaugurated Vice President Kamala Harris, an alumna of Howard University, where the bells tolled 49 times in her honor after she took her historic oath this week as the 49th individual—and first African American woman and HBCU graduate—to hold the office.

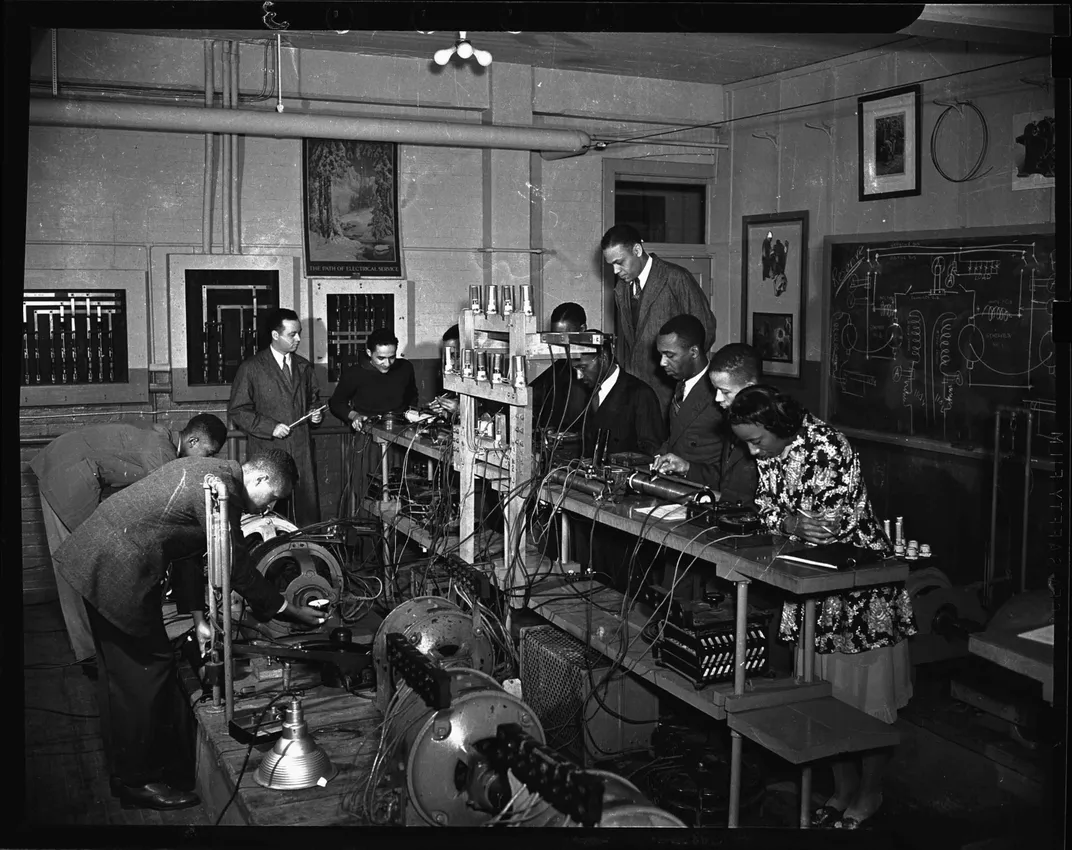

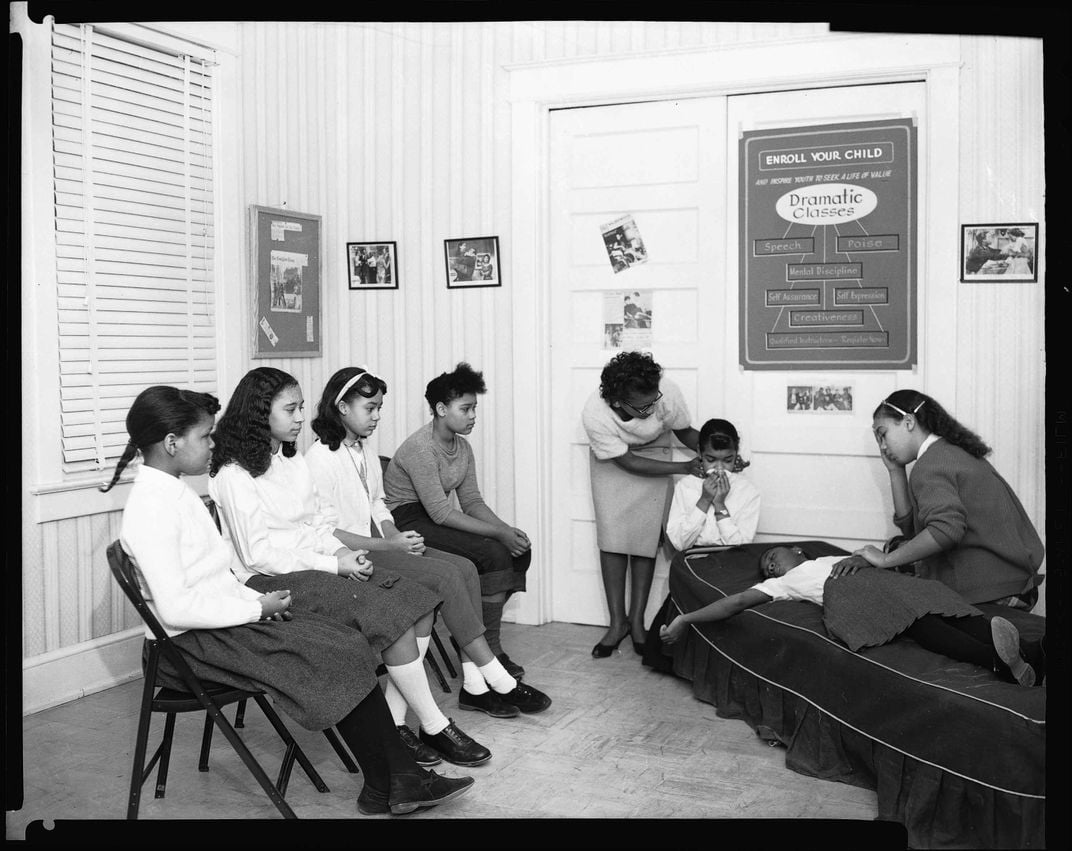

Historically Black colleges and universities are both incubators and accelerators of their students’ talent, intelligence and potentiality in a daily immersion in their heritage and investment in their future.

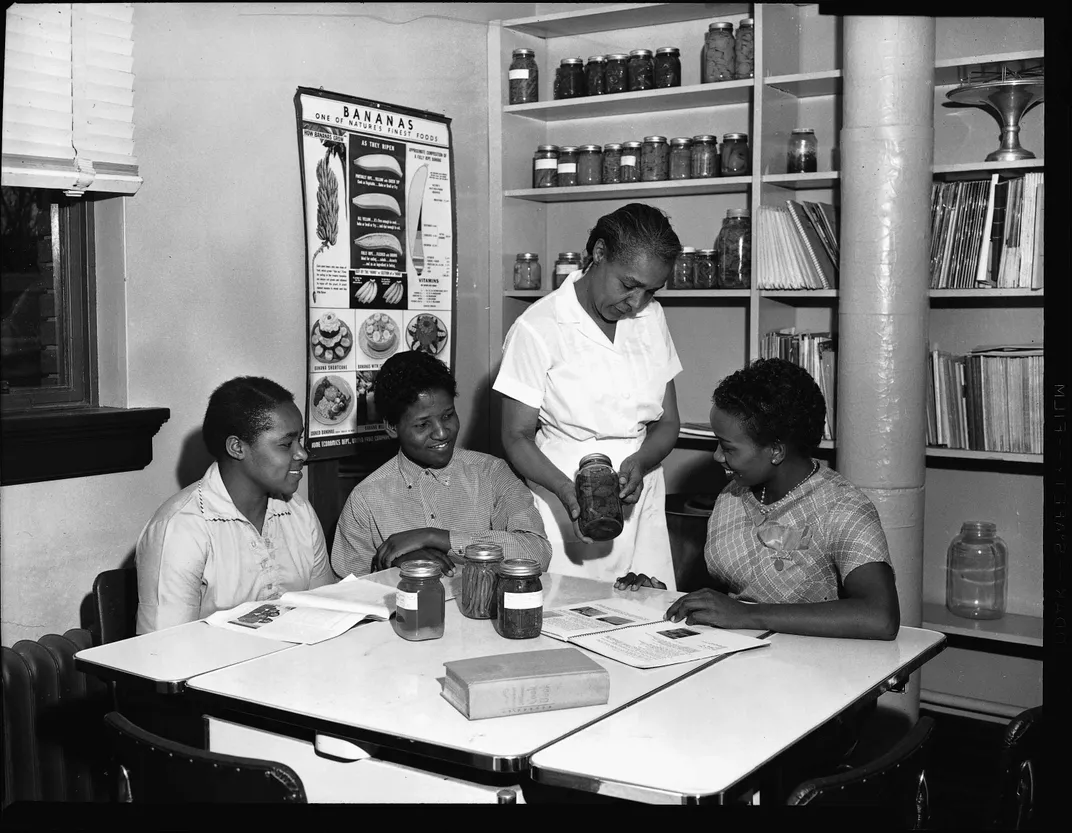

“Being surrounded by people that look like you is empowering in ways that you may not even think about consciously—seeing Black women who are scientists, dancers, writers, doctors, lawyers, means that you just assume that you can be that too,” says Kinshasha Holman Conwill, a Howard University alumna and deputy director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C., home to a comprehensive collection of materials related to the HBCU experience. (Another archive of images taken by Washington D.C.'s renowned photographer Robert S. Scurlock features many scenes and happenings at Howard University and is housed at the National Museum of American History.)

“There's nothing quite like being on a campus where you see these people every day when you're at that very vulnerable college student age. The atmosphere of people who share a common desire to strive, excel and achieve versus being surrounded by people who don't believe you can reach your potential—it's almost like a magic and it's very important,” says Conwill.

Interest in HBCUs has surged and subsided over the course of their long and storied histories—the oldest of them, Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, was founded in 1854 as an all-male college and didn’t start admitting women until 1953—but collectively, they have consistently enrolled more Black women than men every year since 1976. As of 2018, those women, eager to thrive academically and set their individual courses in leadership, comprise 62 percent of students.

Still, when it’s time to hire and be hired, Black women have struggled for parity in pay, title and, in academia, tenure ladders, even and sometimes especially at HBCUs, where the social justice of gender equity is often conflated with social justice around race. Women fortify their leadership, they command leadership, they demonstrate leadership. So how do HBCUs cultivate Black women in a way that predominantly white institutions have not?

“I don't know that they necessarily do,” argues Gaëtane Jean-Marie, dean and professor of educational leadership at Rowan University. She has extensively researched Black women in leadership in the education field in general and at HBCUs specifically, and in one study, she says, participants talked about their encounters at the intersection of race and gender, both at predominantly white institutions and at HBCUs.

“They expressed challenging experiences in both contexts where they had to prove themselves, that they were still judged. In some cases, they were the first to integrate schools during that time when they were young,” says Jean-Marie. “One of my participants was questioned, ‘What are you doing in the classroom? You don't belong in this college classroom that's full of men.’”

Holman Conwill says the HBCU experience fortified her professional career and made her more vigilant in the execution of her goals and responsibilities. Knowing what that experience did for her, she believes the election of Vice President Harris will bolster Black women’s leadership opportunities and, after the closure of six HBCUs in the past 20 years and near-closure of at least three others, this historic moment and heightened HBCU pride will elevate interest in historically Black institutions, particularly for women.

“It reinforces for those of us who know and love those schools, what we've known and loved about them all along—that they are wonderful environments where one can be nurtured, protected and loved, and where excellence is the standard,” she says.

Harris has made “Black life part of the lexicon of America in a profound way, taking not a thing away from President Obama, one of the finest Americans to walk this country. But because she's so grounded in a Black institution, it makes all the difference in the world that she graduated from Howard and not from Harvard,” Holman Conwill added.

“So her rise as the first African American woman to be a vice presidential candidate in a major party means that in finding out about her background, people had to learn what an HBCU is and remember the order of the letters. And for those people who couldn't find Howard university on a map, they found it—and Fisk, Hampton, NCCU, Tuskegee, all the other schools. The sites of Black excellence are being discovered,” says Holman Conwill.

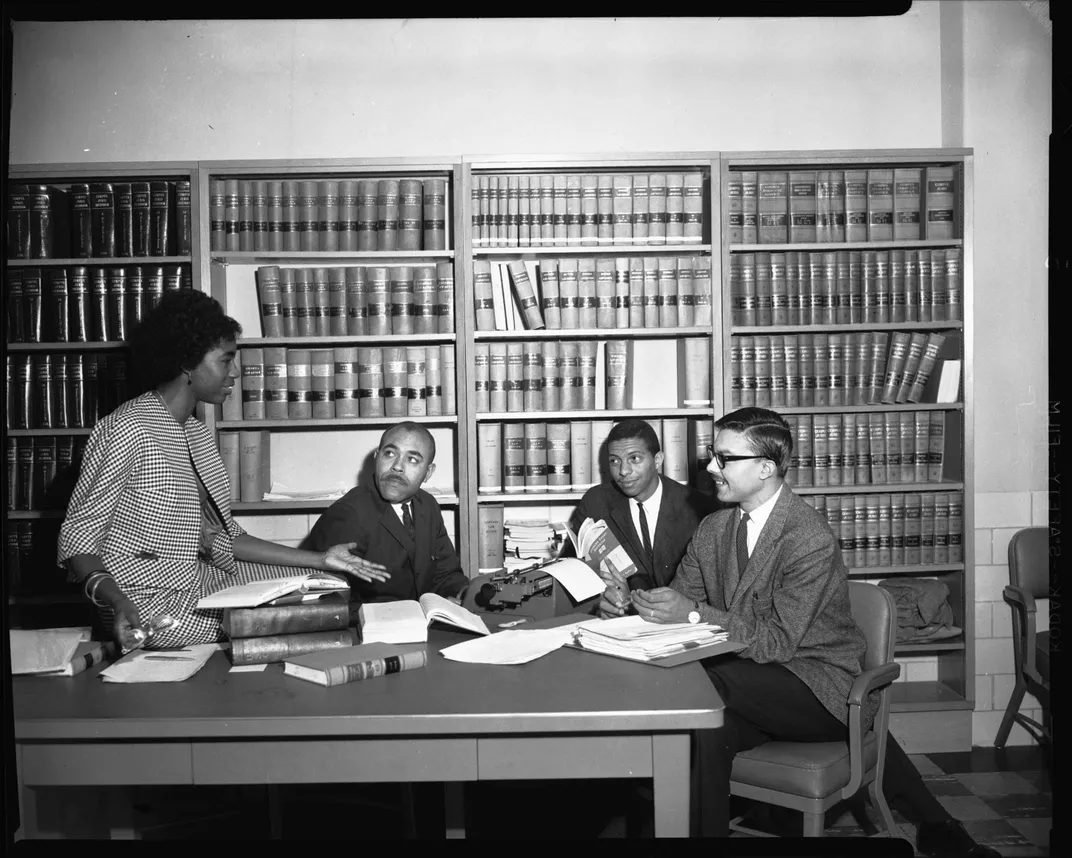

On Inauguration Day, Kamala Harris took the oath of office with her hand on a Bible owned by Thurgood Marshall, a two-time HBCU alum who earned his undergraduate degree at Lincoln University and his juris doctorate at Howard University. Inauguration is always an event but it’s never been a celebration of HBCU joy, a moment for HBCU grads to feel vicariously honored and elevated and equalized against the lie of “not as good.”

Black women flooded social media in their pearls and Chuck Taylors to honor “Kamala Harris Day” and her sorority, Alpha Kappa Alpha. A lineup of iconic HBCU bands battled at the inaugural kick-off and Howard University’s Showtime Marching Band escorted its prestigious alumna to her national platform at the U.S. Capitol. And the election win that made the pomp and celebration all possible was galvanized by Georgia’s voting rights activist Stacey Abrams, and a graduate of Spelman, and Atlanta mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms, an alumna of Florida A&M University.

As the National Museum of African American History and Culture expands and curates its HBCU collection, the women who are leading in every industry, sector and segment—from politics to religion, entertainment to STEM—are making Black women in leadership more visible, more attainable.

“We don't want to be a figurehead or just being a figure of representation. We also want to be able to influence policy,” says Jean-Marie. “It's not enough for us to have a seat at the table. It’s time for us to seize the moment and speak up at the table.”

:focal(300x176:301x177)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/84/f3/84f3de32-8552-4c11-9b72-1f6868c4b2d8/longform_mobile.jpg)

:focal(600x314:601x315)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2f/8a/2f8a407e-d420-4997-8093-bfef65f54d5c/social-media-dimensions.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/janelle.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/janelle.png)