How This Washington, D.C. Museum Redefined What Museums Could Be

Fifty years after its founding, the Smithsonian’s beloved Anacostia Community Museum continues to tell stories heard nowhere else

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/77/85/7785c223-656b-4015-9cd8-5c997d05502b/anac1.jpg)

As opening speakers kicked off 50th anniversary festivities at the Smithsonian's Anacostia Community Museum last Friday, assembled audience members—many of them neighborhood natives—were visibly emotional. Nodding their heads and offering occasional vocal affirmations during speeches, and chatting convivially with one another in between, those gathered seemed at home in the museum, assured of their place there and glad to be sharing the moment with longtime friends and fresh faces alike.

The vibe in the assembly room could not have been more appropriate given the Anacostia Museum’s mission: to bring the people of a historic D.C. region together in appreciation of the many cultural narratives playing out in their community. The 1967 founding of the museum, sited at the heart of a predominantly African-American part of the city, was at the time a radical act. Civil rights agitators were making big waves in Washington then, and the Anacostia project became a beacon of solidarity.

Richard Kurin, a Smithsonian distinguished scholar and ambassador at large, asserted in his remarks that the groundbreaking nature of the museum was the result of the vision of founding director John Kinard. Initially, Kurin recalls, the concept was much less daring: the museum would simply house miscellaneous Smithsonian artifacts, a gesture to show that the Institution cared about regions like Anacostia. Under Kinard, though, it took on a much more ambitious and innovative set of priorities.

At the heart of Kinard’s philosophy, Kurin says, were the ideals of “community, participation and expression.” Far from a mere branch of the Smithsonian, the Anacostia Museum would become a cultural nexus in its own right. With a smile, Kurin describes Kinard as a “rabble-rouser”—one with the “chutzpah” necessary to turn a modest outreach project into something much greater.

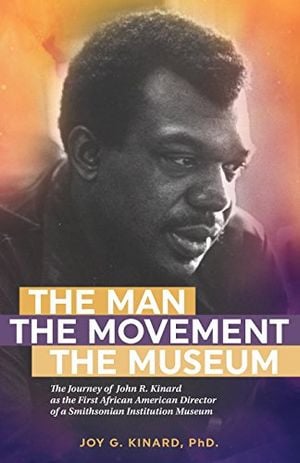

John Kinard’s daughter Joy, author of the just-published memoir The Man, The Movement, The Museum, was unable to hold back tears as she addressed the crowd. “I grew up in this museum,” she says, thinking back on the embracing atmosphere of Anacostia, and the constant busyness of her visionary father. She says John was always either at the museum or in the big city attending important meetings. He was a “storyteller,” she remembers, and writing his own story felt like the least she could do to repay him.

Calling the book “a labor of love,” Joy stresses the impact her father’s work had on future generations. The newly opened National Museum of African American History and Culture, situated right on the National Mall, is “a manifestation of the work done here,” she asserts with pride. “I am so full today.”

Landle Edward Jones, the CEO of Crazee Praize Nation, spoke eloquently of the philosophy of John Kinard, who he says was adamant that museums had “responsibilities that go beyond collecting treasures.”

“A museum must be an instigator of new cultural and social trends,” Jones says, “a catalyst for change in the environment it shares with its constituency.” Kinard’s genius was in “meeting the public on their own terms.”

A fitting follow-up to this comment was the spirited performance of gospel artist Clifton Ross III, who enlisted the help of his audience as he belted out passionate call-and-response numbers. “Thank you, Lord / for all you have done for me” was the driving sentiment in his first piece; members of the crowd joyously clapped and sang along. Ross’s second song revolved around perseverance and optimism. “It’s a long time coming,” he sang, “but I know change is going to come.”

This kicked off a day filled with a host of exultant community-oriented performances, all of them open to members of the Anacostia public.

Local musician Brent, of the band Brent & Co., played New Orleans-inspired music on an acoustic guitar, his voice husky, his body bouncing with the beat, his head bobbing and tilting with each note. As he prepared to start in on his second song, he shared memories of Anacostia, telling stories while strumming the opening chords in an effortless holding pattern.

A pair of dancers from Capitol Movement Dance Company delivered graceful routines. The first dancer’s performance was characterized by sweeping, arcing movements of the arms, and seamless transitions from a standing position to the floor and back. Her emotion was plain on her face throughout. The second dancer, a tap specialist, moved her own arms as though she were swimming through the air. The staccato of her tap shoes aligned perfectly with the syncopated guitar tune she was dancing to.

Kuumba Learning Center, an Anacostia community mainstay, was also represented. First, a teacher led a group of elementary school-age students in a birdlike dance number, in which bodies glided and soared to a song called “We’ll Rise Up.” Then, an older batch of students, colorfully attired in traditional African garb, proudly delivered their school anthem, “Welcome to Kuumba,” informing a delighted crowd that “creativity, self-identity, this is how we roll.” In their final piece, the Kuumba kids clapped and swayed side to side, calling attention to “our African roots” and repeating the rallying cry “Black power! / Organize! / Always focused, / freedom on our minds.”

Outside the museum, on the lawn, visitors were treated to a show by the Garfield Elementary School drumline and cheerleaders. The energetic drum coach asked the crowd for permission to brag about his kids a little—he noted that the drumline had gone toe to toe with high school squads in recent competitions, and had more than held their own. The sound of the drums was crisp on the warm afternoon, and the dancing of the navy and white-uniformed cheerleaders provided a dynamic complement.

Other events included additional song and dance, a spoken word recital, and a book signing by Joy Kinard.

The exhibitions on display in the museum served as a fitting backdrop for the event. “Your Community, Your Story: Celebrating Five Decades of the Anacostia Museum” is a loving retrospective assembled for the occasion of the jubilee. It is now open to all. Occupying the heart of the museum space is the “Gateways/Portales” display, which looks critically at the experience of those with Latin roots living in the D.C. community, as well as those of Baltimore, Maryland; Charlotte, North Carolina; and Raleigh-Durham, North Carolina. It will be on view through January.

The resounding message of the Anacostia Community Museum is one of acceptance and understanding. It is a place where visitors can expect to walk in the shoes of others for a while, and come to terms with stories that may be substantially different than their own. Fifty years after its founding, such a space is as essential as ever for keeping bonds strong in troubled times.

“We need to understand how important institutions like this are,” Joy Kinard says, “to support local history and what people have done.” To Kinard and the members of her community, the museum will forever be an emblem of triumph and resilience, a living rejection of bigotry both past and present.

“I wasn’t here 50 years ago,” Kinard says, “but I have an inkling of what happened. And that day means so much—not just for Washingtonians, but people around the nation.”

On Saturday, October 7 from 11 a.m. to 4 p.m., the Anacostia Community Museum will be hosting a “Block Party” featuring local vendors, live music, food trucks and ample activities. The event will be held at the museum, and will be open to the public. Admission is free. The new exhibition “Your Community, Your Story: Celebrating Five Decades of the Anacostia Museum” is on view through January 6, 2019.

The Man, The Movement, The Museum: The Journey of John R. Kinard as the First African American Director of a Smithsonian Institution Museum

The dramatic scope of John Kinard’s extraordinary life is richly detailed by his daughter, Dr. Joy G. Kinard. Dr. Kinard guides us to an appreciation of her father's intuitive genius and wiliness to defy the museum world's "standard, polite" expectations and assumptions. Since 1967, the Anacostia Neighborhood Museum—the first federally funded African American museum and unit of the Smithsonian Institution— has served as a model for museums around the world. Using the lens of John Kinard's life, this book gives every reader a much deeper understanding of how we all have the power to make a difference in the world.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)