How Apollo 8 ‘Saved 1968’

The unforgettable, 99.9 percent perfect, December moon mission marked the end of a tumultuous year

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/61/e6/61e63cf9-f289-4b5e-8eff-ced34e35022e/apollo8.jpg)

The Apollo 8 astronauts watched the desolate, crater-pocked surface of the moon pass beneath them. Then, something unexpectedly stunning happened. Rising above the horizon was a beautiful sphere, familiar and yet unfamiliar—a blue marble that beguilingly stole the space voyagers’ attention. What they saw was heart-stopping, heavenly, halcyon—home.

This image would capture the human imagination, and ironically, it could only be seen when Earthlings left home for the first time. The three men traveled hundreds of thousands of miles to look back and discover the jewel they had left behind. It was so far away that a raised thumb could hide this sapphire oasis in the void. “Everything you’ve ever known is behind your thumb,” said Apollo 8 astronaut Jim Lovell decades later. “All the world’s problems, everything. It kind of shows you how relative life is and how insignificant we all are here on Earth. Because we are all on a rather small spaceship here.”

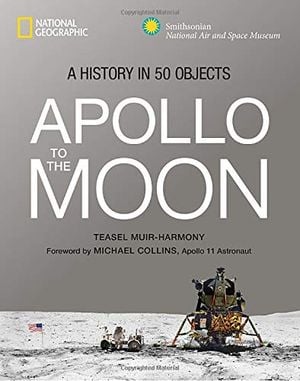

Astronauts Frank Borman, Bill Anders and Lovell were not supposed to visit the moon at all. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration had assigned these men to Apollo 9, a fairly routine test of the lunar excursion module (LEM) in Earth’s orbit. But during the summer of 1968, U.S. officials feared an unexpected Soviet jaunt to the moon, so just 16 weeks before the scheduled liftoff, they reassigned the astronauts to an incredibly ambitious and dangerous flight. This decision was essential “to put us on the right timeline for Apollo 11,” says Teasel Muir-Harmony, a curator at the National Air and Space Museum and author of the new book, Apollo to the Moon: A History in 50 Objects.

Flight Director Christopher Kraft told Borman’s wife Susan that the odds of her husband’s return were fifty-fifty. As launch day arrived on December 21, 1968, many “engineers and scientists at NASA question[ed] whether the crew” would ever return.

Apollo to the Moon: A History in 50 Objects

A celebration of the 50th anniversary of NASA's Apollo missions to the moon, this narrative by curator Teasel Muir-Harmony uses 50 key artifacts from the Smithsonian archives to tell the story of the groundbreaking space exploration program.

There was nothing easy about this flight. The big Saturn V missile that would power the trio’s ship into space had launched only twice. It succeeded once and failed miserably on its second liftoff. And riding a rocket with such a short and unencouraging record was just the astronauts’ first potential obstacle. “Barreling along in its orbit at 2,300 miles per hour the moon was a moving target, some 234,000 miles from Earth at the time of the astronauts’ departure,” wrote author Andrew Chaikin. “In an extraordinary feat of marksmanship, they would have to fly just ahead of its leading edge and then, firing the Apollo spacecraft’s rocket engine, go into orbit just 69 miles above its surface.”

Borman, Lovell and Anders relied on nearly perfect performance from computers and engines to take them to the moon, into lunar orbit, back toward Earth, and through a thin slice of atmosphere to splash down in the Pacific. “Everyone involved accomplished many, many firsts with that flight,” says Muir-Harmony. “It was the first time humans travelled to another planetary body, the first time the Saturn V rocket was used, the first time humans didn’t experience night, and sunrises, and sunsets, the first time humans saw Earthrise, the first time humans were exposed to deep-space radiation. They traveled farther than ever before.”

Some of the crew’s most critical engine burns, including the one that would return Apollo 8 to Earth, occurred when they were on the far side of the moon and had no way of communicating with the rest of humanity.* They fired their engines while the world waited in suspense. Many children went to bed on Christmas Eve 1968, not with visions of sugar plums dancing in their heads or even with dreams of shiny new bicycles lifting their hearts. Instead, they worried about three men far from home—and whether their engine would work correctly and send them back or whether they would die in unending lunar orbits.

The astronauts seized the attention of at least one-fourth of the planet’s residents. More than 1 billion people were said to be following the flight. The Soviet Union even lifted its Iron Curtain enough to allow its citizens to follow this historic moment in human history. In France, a newspaper called it “the most fantastic story in human history.”

Day in and day out, people around the world listened to communications between the Johnson Space Center and the distant Apollo 8. A complete record of communications is available online today. Much of the back-and-forth sounded like business as usual, three men at work, but there were rare moments. Lovell spontaneously created the word “Earthshine” to explain what was obscuring his vision at one point. Until that moment, no one on Earth knew that the planet emitted a noticeable glare.

To add a touch of poetry to their Christmas Eve broadcast, the astronauts read the first ten verses from the Bible’s book of Genesis, with visual images of the barren moon rushing beneath their words. The reading ended with Borman saying, “God bless all of you, all of you on the Good Earth.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7a/5d/7a5defc8-262a-427b-8755-eb5a063a8755/6972225_large.jpg)

Borman had been advised to “say something appropriate,” says Muir-Harmony for that Christmas Eve broadcast, and he had sought input from others before Apollo 8 lifted off. The reading from Genesis, she says, “was done with the expectation that it would resonate with as many people as possible, that it wouldn’t just be a message for Christians on Christmas Eve.” Its emotional impact startled many viewers, including CBS anchorman Walter Cronkite, whose eyes filled with tears. (In 1969, famed atheist Madalyn Murray O’Hair filed suit against the then-head of NASA Thomas O. Paine challenging the reading of the Bible by government employees. One federal court dismissed the case, and in 1971, the Supreme Court refused to hear an appeal of the lower court’s dismissal.)

This unprecedented flight has been described as “99.9 perfect.” And when the three astronauts set foot on the aircraft carrier USS Yorktown after splashdown, Mission Control erupted in a celebration swathed in cigar smoke. The home team never cheered the small victories along the way to successful flights. It wasn’t time to rejoice until the astronauts stood aboard a U.S. ship. Today, the Apollo 8 command module, an artifact in the collections of the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum, is on loan to Chicago’s Museum of Science and Industry, where it takes pride of place in the museum’s 50th anniversary celebrations of the historic mission. The command module was crucial to the astronauts’ success. After the 1967 fire on Apollo 1 that killed three astronauts, NASA had put a great deal of effort into guaranteeing that every element of this craft was flawless, Muir-Harmony says.

Once the Apollo 8 astronauts had visited the moon, space enthusiasts began to foresee greater things. Paine quickly predicted that this flight marked just “the beginning of a movement that will never stop” because “man has started his drive out into the universe.” Borman told a joint meeting of Congress that he expected colonies of scientists to live on the moon. “Exploration is really the essence of the human spirit and I hope we will never forget that,” he told his audience.

The New York Times reported that “the travels that earned immortality for Marco Polo, Columbus and Magellan all fade before the incredible achievement of the Apollo 8 crew.” Time named the crew as 1968’s Men of the Year. And Bill Anders’ “Earthrise” photo became a powerful symbol of the budding environmental movement, while Lyndon Johnson was so touched by the vision of a unified world with no national boundaries that he sent a print to every world leader. This mission was “the most important flight of Apollo by far. No comparison,” said Kraft. “Apollo 8 was a major leap forward, and major leap forward of anything we had planned t0 do.”

Fifty years later, the names Frank Borman and Bill Anders are not well recognized. Jim Lovell was made famous by Ron Howard’s 1995 movie about the saga of Apollo 13’s near failure, but neither the first men to leave the Earth nor their mission are prominent fixtures in America’s historical memory. Even more lost are the 400,000 other humans who labored to make this miraculous voyage possible. That in no way diminishes their accomplishment or its effect on people who found inspiration in their fearless feat.

At the close of the turbulent year 1968, one American wrote to Borman with a simple message: “You saved 1968.” The assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy, the race riots in many American cities, the protests, the war and a president’s political downfall marked that year as one of the most memorable in 20th century history, and the Apollo mission, indeed, allowed it to end on a momentous note. It proved that human beings could do more than struggle, oppress and kill: They could accomplish something wondrous.

On Tuesday, December 11, at 8 p.m., the National Air and Space Museum commemorates the 50th anniversary of Apollo 8 with an evening at Washington National Cathedral. A live webcast will stream here, on the museum’s Facebook page and on NASA TV.

*Editor's Note, December 13, 2018: A previous version of this article referred to the far side of the moon by an incorrect term. The story has been edited to correct that fact.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)