How to Avoid the Pitfalls in the Politics of Graphic Messaging

The director of the National Portrait Gallery offers a few pointers on how to acquire visual intelligence

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/75/41/7541e891-04d8-4d02-b3d5-61c00dbb1f45/campaign-logos_1024.jpg)

Last week the Trump-Pence campaign released a logo intended to show unity and strength with reference to the American flag, and instead found itself engulfed in a fit of crude Internet commentary when the interlocking letters T and P were widely interpreted as a sexual act.

Two weeks prior, Donald Trump tweeted an unflattering image of Hillary Clinton juxtaposed against a background of money and a six-pointed star that recalled for many the anti-Semitism of Nazi Germany.

Just to prove that visual miscues are not partisan, Clinton’s campaign logo a year earlier came under fire from people within her own party for presenting a red H—a color associated with the Republican Party—pointing to the right as an apparent gesture towards “right wing” conservative thinking. And the Bernie Sander’s campaign in April was taken to task on social media for placing his electioneering logo on top of an image of Pope Francis, as if to suggest that Sanders had earned the Pontiff’s endorsement.

In a world where images are fast outpacing words as the major means of communication, now might be the time for politicians to become more adept at visual intelligence. One of the best ways to do that is to visit museums to engage more broadly with history, as told through art and design, and more specifically with the language of semiotics—the interpretation, study and analysis of signs and symbols.

The ability to read the signs and recognize that a picture does indeed tell a thousand words, cannot be left to chance or even intuition. As recent discussions over flags, crosses, stars and raised fists demonstrate, what we see or hear is often not what we know or mean.

Museums and libraries are more than repositories of past remembrances; they also serve as vital touchstones of visual culture that resonate today. As Richard Brodhead the president of Duke University said: “Museums are places where we're taught to pay attention.”

Symbols change over time as cultural contexts shift. Take for example the National Portrait Gallery’s iconic Lansdowne portrait of George Washington, which is embedded with a host of meaningful visuals including the rainbow at the top right in the window. The rainbow serves as an 18th-century symbol of God’s blessings on the settlers who had weathered the storms of British oppression and forged a New World.

African American landscape painter Robert S. Duncanson used the rainbow as a symbol of hope for peace at the onset of the Civil War in his 1859 Landscape with Rainbow, currently on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

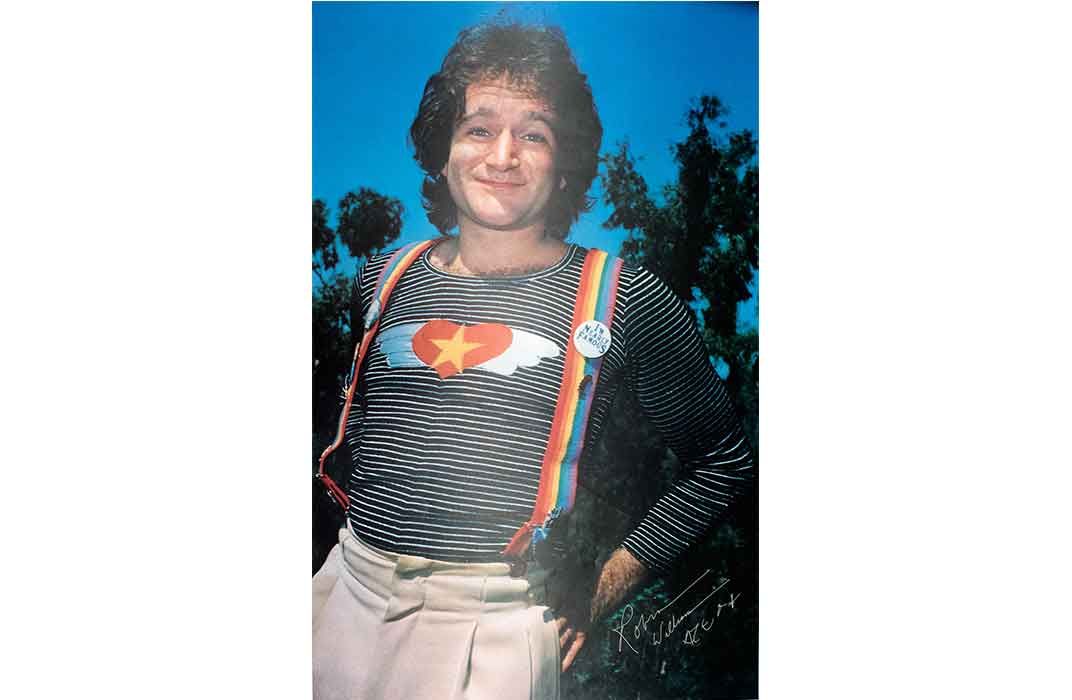

The playful rainbow suspenders worn by comedian Robin Williams in a 1979 photograph by an unknown artist and held in the Portrait Gallery’s collections enlivens the childlike character Mork, the alien from the planet Ork, in the popular television series “Mork & Mindy.”

Today, images of rainbows and the rainbow flag defiantly proclaim pride for the LBGTQ movement. The portrayal of the civil rights activist Harvey Milk on the United States Post Offices’ 2014 Forever Stamp includes the rainbow colors. Milk was one of the nation’s first openly gay politicians. He was tragically murdered in 1978, along with San Francisco Mayor George Moscone, by an assassin’s bullet. Incidentally, the first transgender pride flag, bearing stripes of the traditional pink and blue for boys and girls and white for intersex, is now housed at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

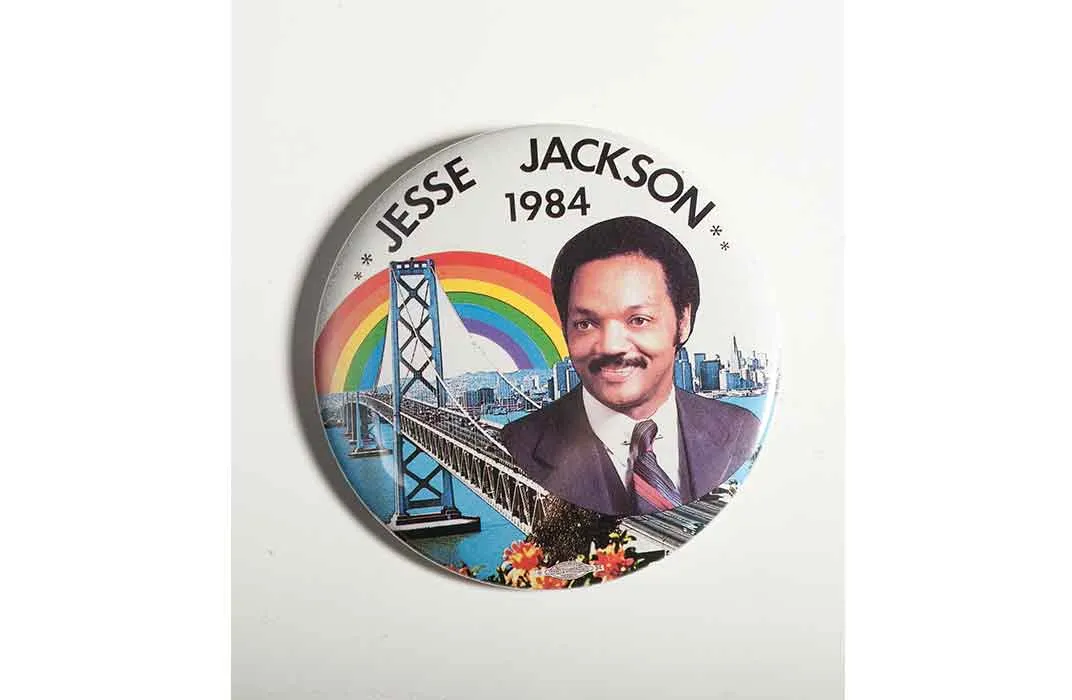

Artifacts and artworks tell meaningful visual stories. Tools developed here at the Smithsonian, like the recently debuted Learning Lab, offer opportunities to search by subject for online discovery and study. A search of the word “rainbow” on this digital database turns up a vast wealth of visuals as depicted in Asian artworks at the Freer and Sackler Galleries to a political button from Jesse Jackson’s rainbow coalition speech at the 1984 Democratic National Convention.

The study of semiotics or ‘reading signs’ may sound complicated, but it is actually something we participate in from childhood and reinforces our place in the world. At the most basic level we know that the color red, for example, is universally understood to mean stop, and green means go, but on the more nuanced side of cultural studies, red may allude to prestige (carpets and labels), revolution (Soviet Russia or Communist China) or love (hearts and roses).

How colors, shapes, words, images and even sounds are communicated often has an historic antecedent deeply connected to human traditions that resonate today. When the Trump campaign referenced a six-pointed star, it wasn’t just the shape that caused offense, but the fact that it was in red, (warning!) and juxtaposed over a background wallpapered with money that harkened back to anti-Jewish propaganda of the 1930s. The words history and made written in white were outlined in the colors associated with the Israeli flag. It wasn’t a single element, per se, that caused the outcry; it was the effect of many visual cultural codes coming together that did.

In the past, understanding the basics of law, the principles of business and economic theory, and how the military works have been required knowledge for positions of leadership.

Of the 43 U.S. presidents, for example, one-third served in the military, more than half practiced law, and almost all studied some form of history.

To be a good writer, or better yet, a great public speaker comfortable in front of a crowd and camera is highly valued; and those that were truly extraordinary such as Abraham Lincoln, possessed what historian Doris Kearns Goodwin calls "emotional intelligence," the ability to empathize with others and when necessary, apologize for personal failures and oversights.

Gaining visual intelligence means recognizing that communities differentiate themselves through symbols that are often appropriated from history in order to add to or upend the previous cultural narratives. Therefore to be visually intelligent is to understand how popular culture has worked in the past, check sources for each new iteration and remember that communication while always fluid and often political, rarely exists in a vacuum.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/KSajet_portrait_orange_1.13.JPG)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/KSajet_portrait_orange_1.13.JPG)