How the Backwater Town of Washington, D.C. Became the Beacon of a Nation

As the Anacostia Community Museum delves into daily life in a city at war, author Ernest B. Furgurson recalls the nascence of a city on the verge

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ca/88/ca88d2d2-7d34-4f79-90b1-3129f69cca21/balloonviewwashingtonweb.jpg)

When President-elect Abraham Lincoln slipped into Washington’s Baltimore & Ohio station at dawn on February 23, 1861, he looked up at the first bare bones of the new Capitol dome. It was an apt illustration of the nation’s capital at that historic moment—a city of grand ambitions, more than of finished stone and mortar. Many months of bureaucratic infighting and wartime shortages would pass before the magnificent dome rose complete above the city.

Far down the Mall, past the brick castle of the Smithsonian Institution, the Washington Monument was a 156-foot stub, its construction halted by politics and scandal. Employees of the Treasury and the Patent Office worked in quarters still being built. State, War and Navy departments closely flanked the president’s mansion. Between the executive and legislative poles of government, cattle and pigs roamed streets that were dusty in summer and muddy in winter. Only Pennsylvania Avenue itself and the nearby stretch of Seventh Street were paved, with broken cobblestones. Urban sophisticates from farther north made jokes about Washington as a rustic backwater.

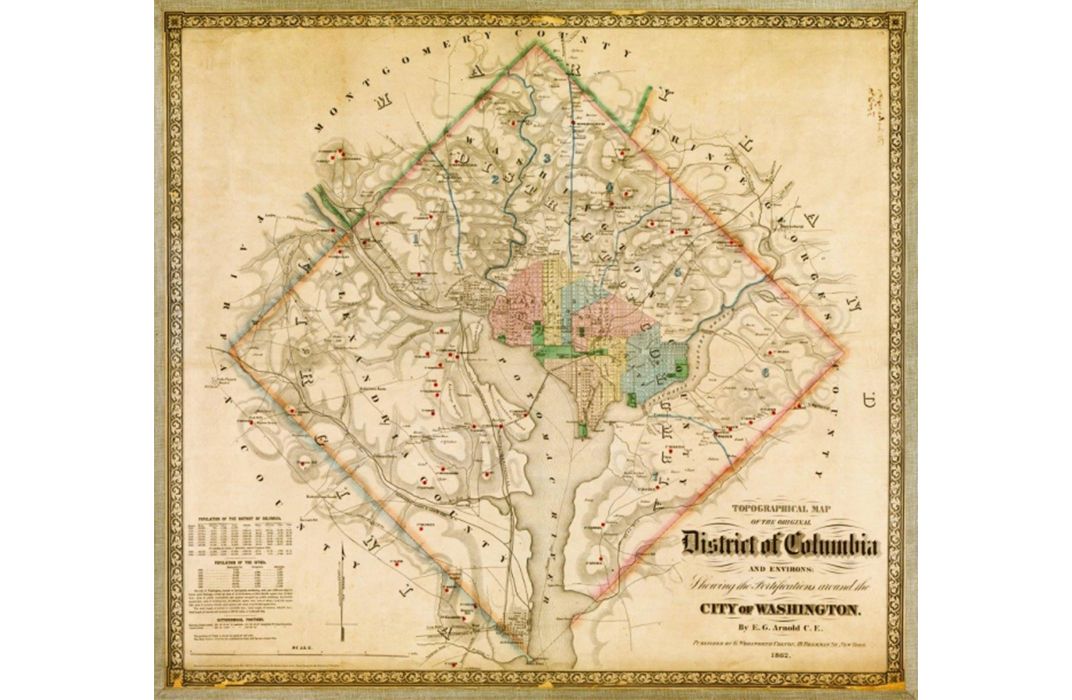

In a nation of 33 states and some 32 million Americans, only 75,000 lived within the District of Columbia, only 61,000 of these in Washington City proper. Nearly 9,000 were in Georgetown, still a separate town within the District, and more than 5,000 in the rural reaches beyond Boundary Street, which ran along today’s Florida Avenue. The Virginia portion of the original 10-mile-square District was ceded back to the state in 1847, but by breeding and culture, the city was still deeply southern. In 1860, 77 percent of the District’s population had roots in Maryland or Virginia; in Georgetown, less than ten percent originated north of the Mason-Dixon line. And to better understand the monumental dynamics of this city in transistion, a new exhibition, "How the Civil War Changed Washington," at the Smithsonian's Anacostia Community Museum, examines the burgeoning capital's infrastructure, social imperatives and daily life. The show delves into the lives of such prominent individuals as Clarina Howard Nichols, a feminist and advocate for African American women and friend to Mary Todd Lincoln, and Solomon Brown, an African American poet, scientific lecturer and a Smithsonian employee, among others. The exhibition also explores the city's legacy with a fascinating array of artifacts of the era.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/40/7b/407b091f-4f5f-480c-8550-9fd4ab23b55a/unidentifiedcontrabandweb.jpg)

When Lincoln first arrived in 1847 as a freshman congressman, human beings were bought and sold at markets within blocks of the Capitol. Although the slave trade was outlawed in the District in 1850, possession of slaves remained legal, and across the Potomac in Alexandria, business continued as before. About a fifth of the District’s population was African-American. Some 3,000 were slaves, mostly household servants, and about 11,000 free, many of them skilled artisans, some respected entrepreneurs like James T. Wormley, who was General in Chief Winfield Scott’s landlord. Slave or free, they were still governed by the Maryland “black code” left over from creation of the District in 1791. That meant strict punishment if they assembled without permission, walked the streets after 10 p.m. or violated other arbitrary rules that limited their daily lives. Free blacks risked sale back into slavery if caught without their residence permits. Whatever their status, they were essential in building the city and making it work.

At loftier levels of society, in business and politics, in the tiny diplomatic colony and among senior military and naval families, crinolined hostesses strived to match the style of Charleston or Philadelphia. Social life was busiest when Congress was in session, which in those pre-air conditioning days was in winter and spring; business picked up then in hotels and saloons along Pennsylvania Avenue. But in early 1861, visitors from afar could agree with the British journalist who said the capital of the young nation was still “In the District of Columbia and the State of the Future.”

In April, the nation plunged into that future.

After the first cannon fired at Fort Sumter, Virginia joined the Confederacy and blockaded the Potomac downriver. In Baltimore, street mobs attacked Union troops headed to Washington, and Maryland burned railway bridges to block more troops from passing, leaving Lincoln pleading, “Why don’t they come?” Fear of invasion rose to near panic in some quarters. Detectives arrested citizens on mere suspicion of disloyalty. General Scott fortified the Treasury, the Capitol and City Hall to be last strongholds. Then when reinforcements did come, by the many thousands, they sprawled into every corner, including the very Capitol, where they defiled halls and chambers as if camping outdoors.

Washington became an occupied city. Hundreds of families fled north, as more had already headed south, among them ranking army officers and officeholders. As fast as they left, swarms of profiteers descended, seeking government contracts for the logistical needs of war. Vast deals would be consummated amid cigars and bourbon at Willard’s Hotel. Plain and fancy prostitutes preyed on ignorant soldiers. Everyone had to sleep somewhere, and strangers commonly shared beds in hotels and boarding houses. After the Union army was rudely turned back at Bull Run that summer, the first wounded soldiers jammed the city’s only hospital. Thousands more would follow, overflowing into homes and government buildings across the city. Working men and women came from cities and farms to construct hospitals, shuffle government papers, and produce munitions at the arsenal at Greenleaf Point, site of modern Fort McNair. Laboring beside slaves and soldiers, they started building a ring of forts to defend the city,

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c8/4b/c84b9f27-78e8-4f49-8356-ec636326421c/tent-life-31st-penn-infantryweb.jpg)

Debate over the root cause of the war was overwhelmed in those early months by the hubbub of secession and mobilization, but neither Lincoln nor the antislavery crusaders of the North could ignore it. Slavery still existed within the Union, in the border states of Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky and Missouri, and in the national capital. Although the president opposed it, he had gone to war to save the Union itself, and resisted any diversion from that cause. But under pressure from abolitionists in Congress, in 1862 he proposed to liberate slaves in Washington, and to make it more politically acceptable by compensating owners for each person freed.

On April 16, 1862, Lincoln signed the bill that forever ended slavery in the nation’s capital and set off jubilant celebration in the city’s black neighborhoods. But carrying out the new law took weeks. Sitting at City Hall on Judiciary Square, a three-man commission had first to assure the loyalty of owners seeking compensation, then to set a dollar figure for each man, woman or child being freed. By midsummer, a total of 2,989 slaves were liberated at an average of $300 each, thus staying within the $1 million allotted by Congress.

This success energized abolitionists who pressed for broader action against slavery, but Lincoln held back, hoping for good news from the front. When it came from Antietam, he announced the Emancipation Proclamation, to take effect on January, 1863. With that stroke, the Union took the moral high ground, strengthening its position in the war and in world opinion. Yet every high point seemed followed by a lower point, month after month.

After Antietam came defeat at Fredericksburg, and then Chancellorsville. The dead and wounded arrived by road, rail and boat, packing makeshift hospitals like that in the Patent Office building, where patients lay surrounded by gadgets sent in by ambitious inventors. On nights when the president stayed at the Soldiers Home to escape heat and annoying visitors at the White House, he was painfully conscious that the national cemetery nearby was rapidly filling with fallen soldiers. The great Union victory at Gettysburg meant still more thousands of casualties. But somehow this time it also signaled a shift of momentum, a feeling that the Union would survive.

On December 2, 1863, the shining symbol of that hope rose atop the Capitol as the statue of Freedom was lifted onto the completed dome with Old Glory flying above, visible across the city and in the outlying camps. Cheers rose from all directions and cannon boomed in the surrounding forts. But the worst was yet to come.

The next twelve months were the costliest of the war. Under U.S. Grant, the army ground its way toward Richmond in one fierce battle after another—the Wilderness, Spotsylvania, North Anna, Cold Harbor. So many casualties flooded into Washington that a vast new cemetery was started on what had been Robert E. Lee’s plantation at Arlington. Lincoln told a gathering in Philadelphia that “the heavens are hung in black”—and returned to find the gloom deepened by news that an explosion had killed 23 young women making cartridges at the Washington arsenal. He admitted that he was unsure whether to run for re-election.

The capital seemed secure behind the 37-mile circle of defenses built on both sides of the Potomac—miles of trees and houses were cleared to build 68 forts with places for 1,500 cannon, linked by trenches, outposts and 32 miles of military roads. That July, Confederate general Jubal Early swung 15,000 troops through western Maryland to give those defenses their only serious test. Thrusting through Silver Spring into the District, Early halted in front of Fort Stevens, less than five miles north of the White House. Thousands of defenders swarmed into the works from the Navy yard, the Marine Barracks and offices all over the capital. As the Confederates organized to attack, Lincoln himself rode out and witnessed a sharp exchange of gunfire. But the next morning, when Early saw the first reinforcements rushed from Grant’s army filing into the defensive works, he withdrew his army back across the Potomac.

UPDATE 2/26/2015: A previous version of this story incorrectly identified Clarina Howard Nichols as an African American.

Boosted by the Union army’s capture of Atlanta in September, Lincoln not only ran for re-election, but won convncingly, and from there it was downhill to Appomattox. When news of Lee’s surrender arrived, a 500-gun salute rattled the windows of Washington. Young and old rushed into the rainy streets singing and shouting, surrounding the White House and calling for the president to speak. For five days there was euphoria, and then on April 14, at Ford’s Theatre on Tenth Street, a flashy actor named Booth assassinated the great man who had led the nation through mortal trauma.

More than five weeks passed before the soldiers who had won the war lifted the capital out of mourning. For two days in late May, the victorious armies of the Union paraded along the Avenue with battle-stained flags flying. Above them gleamed the Capitol dome, holding aloft the statue that signified Freedom, looking out upon a city that was no longer rustic backwater, but capital of a powerful and unified nation, respected throughout the world.

"How the Civil War Changed Washington" is on view February 2, 2015 through November 15, 2015 at the Smithsonian's Anacostia Community Museum, 1901 Fort Place, SE. Organized into nine sections covering before, during and after the war and featuring 18 artifacts, the exhibition examines the social and spatial impact of the Civil War, which resulted in dramatic changes in the city.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSCN0003-001.JPG)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSCN0003-001.JPG)