How Black Panther Changed Comic Books (and Wakanda) Forever

The Marvel superhero pounced on the scene in the ‘60s and never looked back

:focal(1103x514:1104x515)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/da/7a/da7a28b9-e71a-4add-bfde-398f2297d233/janfeb2021_b02a_cropped_prologue.jpg)

It was clear from the moment it reached multiplexes in 2018 that Black Panther wasn’t just a hit; it was a phenomenon. The title character, portrayed by the late Chadwick Boseman, became an inspiration to millions of Americans. Black Panther, a.k.a. T’Challa, king of the fictional African nation of Wakanda, stood as a symbol of strength, honor and pride in one’s African ancestry. And the character’s essential qualities—his regal bearing and quiet determination—are captured in his costume, designed for the screen by Ruth E. Carter, the film’s costume designer, who built on the work of Ryan Meinerding, a Marvel artist and character designer.

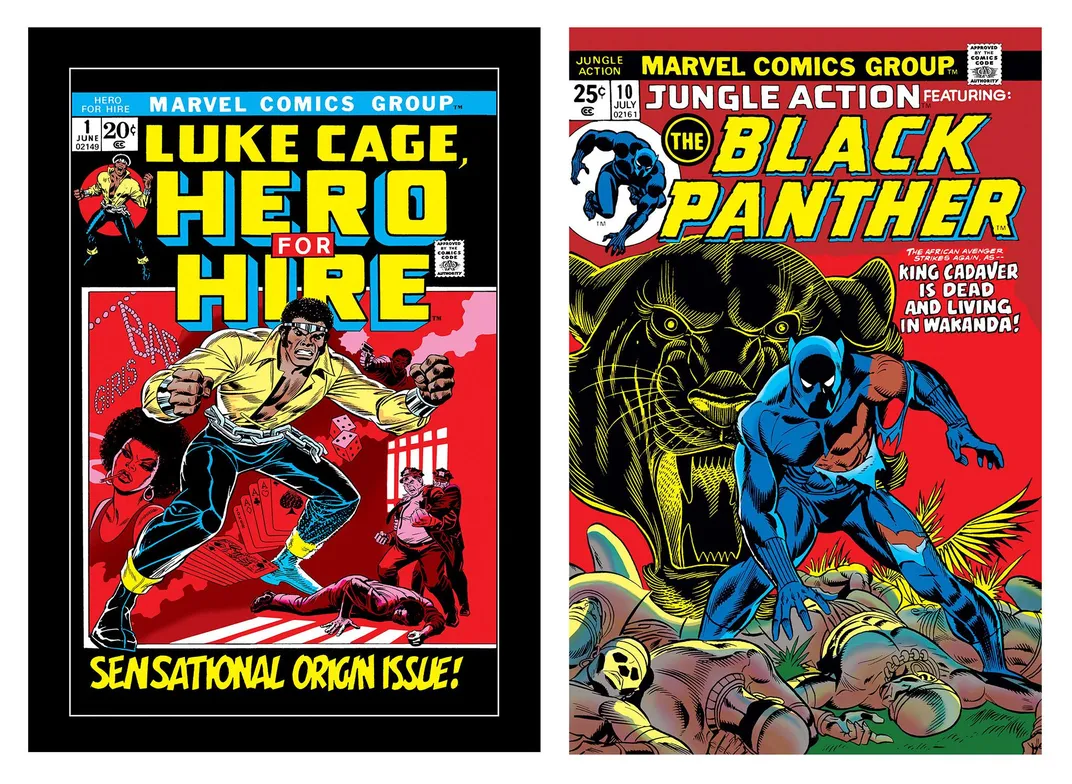

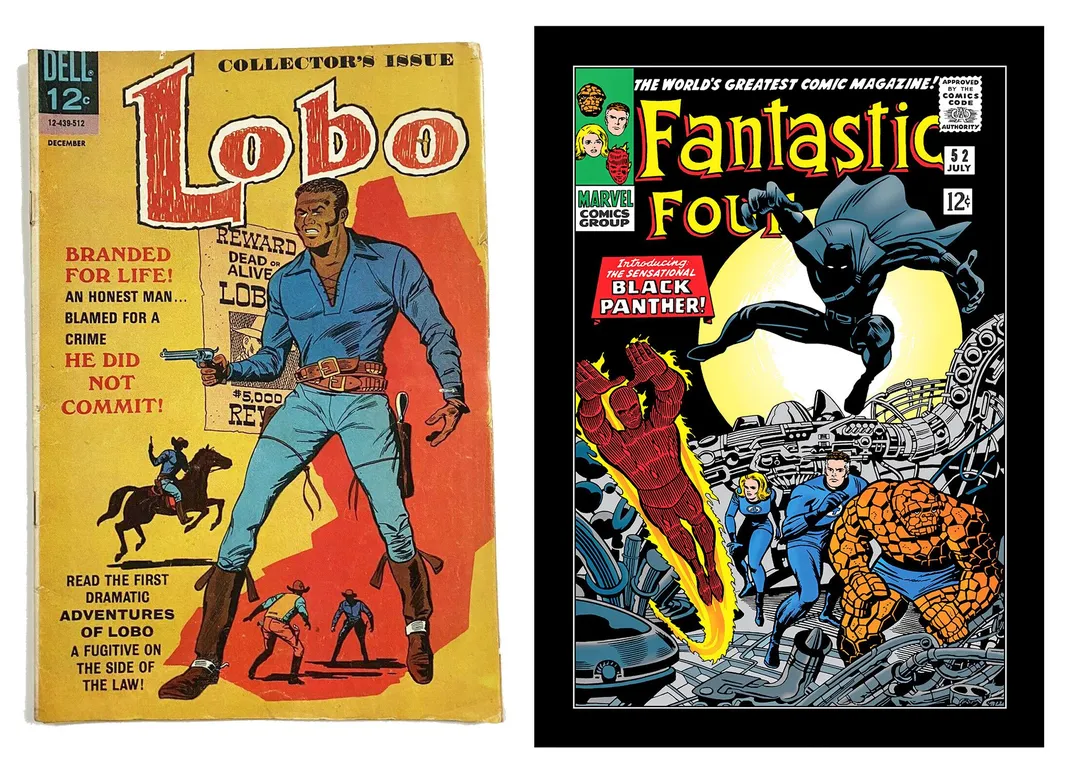

Carter embellished some versions of the costume with raised triangles, which she has called “the sacred geometry of Africa,” given the shape’s long significance to the continent’s art and culture. Her emphasis on the essential dignity of the character captures the ambition of his originators, the writer Stan Lee and the artist Jack Kirby, who debuted Black Panther for Marvel Comics in Fantastic Four #52 in 1966. Following some of the most important moments of the civil rights movement, the comics pioneers wanted Black Panther to break stereotypes and embody black pride.

“At that point I felt we really needed a black superhero,” Lee recalled in a 2016 interview. “And I wanted to get away from a common perception.” Thus, Lee decided to make T’Challa “a brilliant scientist” living in a secret, underground African technoutopia, “and nobody suspects it because on the surface it’s just thatched huts with ordinary ‘natives.’”

But as much as the Black Panther portrayed by Boseman (under the direction of Ryan Coogler) fits this vision, he is also different from the character created by a white writer and a white artist for a white audience more than 50 years ago. Today’s T’Challa is indebted to a generation of black writers and artists who moved beyond mere representation to build a character with more depth than the one dismissed in his first appearance by fellow comics crimefighter Ben Grimm, a.k.a. the Thing, as “some refugee from a Tarzan movie.” In the evolution of the Black Panther, you can see a clear arc in the history of black superheroes—how they’ve become richer, fuller and even inspiring characters.

Black characters have had a fraught history in comic books from the outset. They were “largely relegated to background and secondary roles and characterized primarily through their figurative embodiment of racist stereotypes,” Kevin Strait, a curator at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, says in an interview.

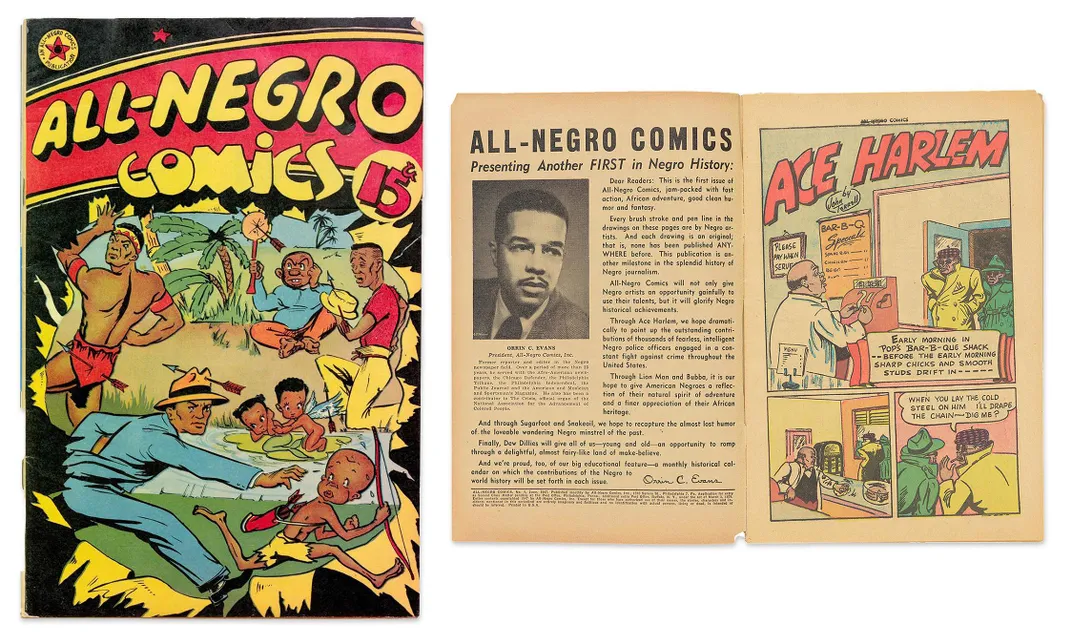

In the 1940s and ’50s, however, depictions began to change. In 1947, a group of black artists and writers published All-Negro Comics, a collection of stories featuring black characters. In 1965, the now-defunct Dell Comics published two issues of Lobo, a western starring a heroic black gunslinger. Still, most comics creators of the period—including the two men who launched Lobo—were white, and like the Black Panther, who was something of a token, most black characters who followed in his path over the next two decades would find themselves in a similar role. Luke Cage, for example, first appeared in Luke Cage, Hero for Hire #1 in 1972, the height of the blaxploitation movement, as a jive-talking hustler who fought crime for money. Nubia, introduced in Wonder Woman #204 in 1973, was just a palette-swapped version of the title character.

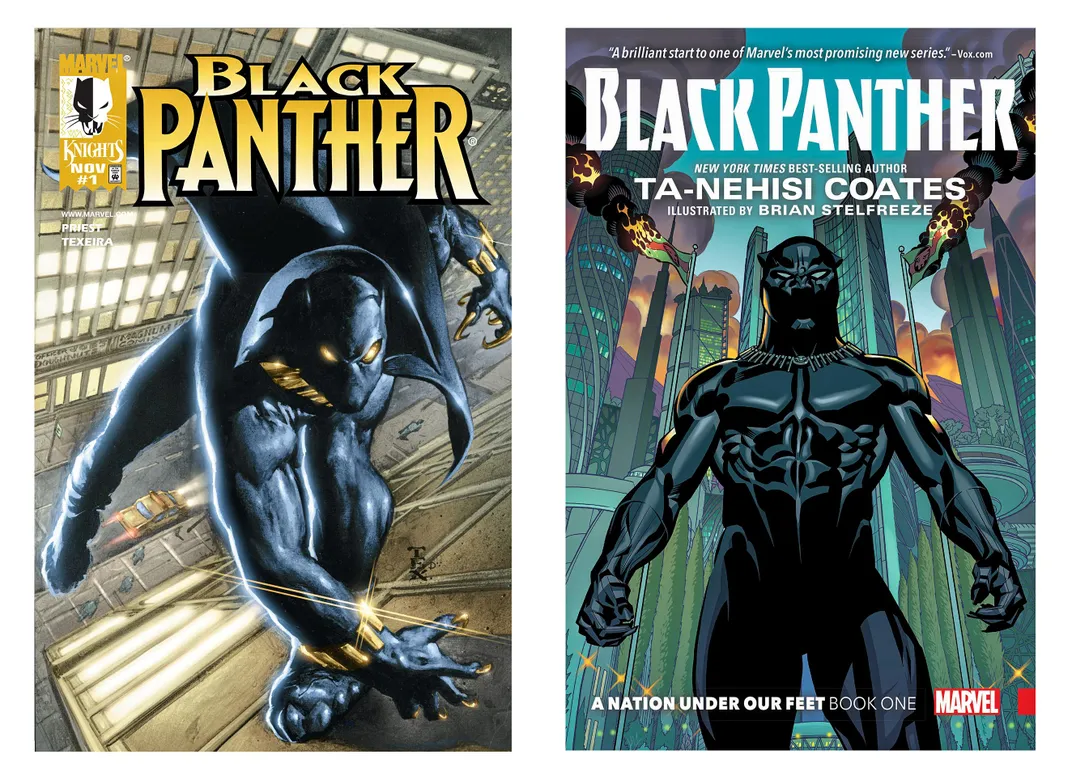

But in 1993, the black superhero saw a new dawn with the arrival of Milestone Media. Founded by black artists and writers, Milestone devoted itself to black and multicultural stories. The comic Icon, for example, presents a Superman-like alien who arrives on Earth to find himself in the antebellum South. There, he takes the form of the first person he sees: an enslaved African American. Milestone set a new standard for black characters, while serving as a talent incubator for writers and artists who would go on to influence the entire industry. Dwayne McDuffie, one of its founders, defined traditional characters like Batman for a generation of new audiences and brought original creations like the black superhero Static to the screen. Christopher Priest, who broke barriers as the first black editor at Marvel and was part of the group that established Milestone, would go on to rejuvenate Black Panther, writing an acclaimed series from 1998 to 2003 that lifted the character from obscurity to the A-list of comics. As written by Priest, the Black Panther is an enigmatic genius who maintains a careful remove from the Western world. It is Priest who shaped the character for the next 20 years, and whose work (along with that of Ta-Nehisi Coates, who began writing the character for the page in 2016) was the foundation for the hero we saw in the film.

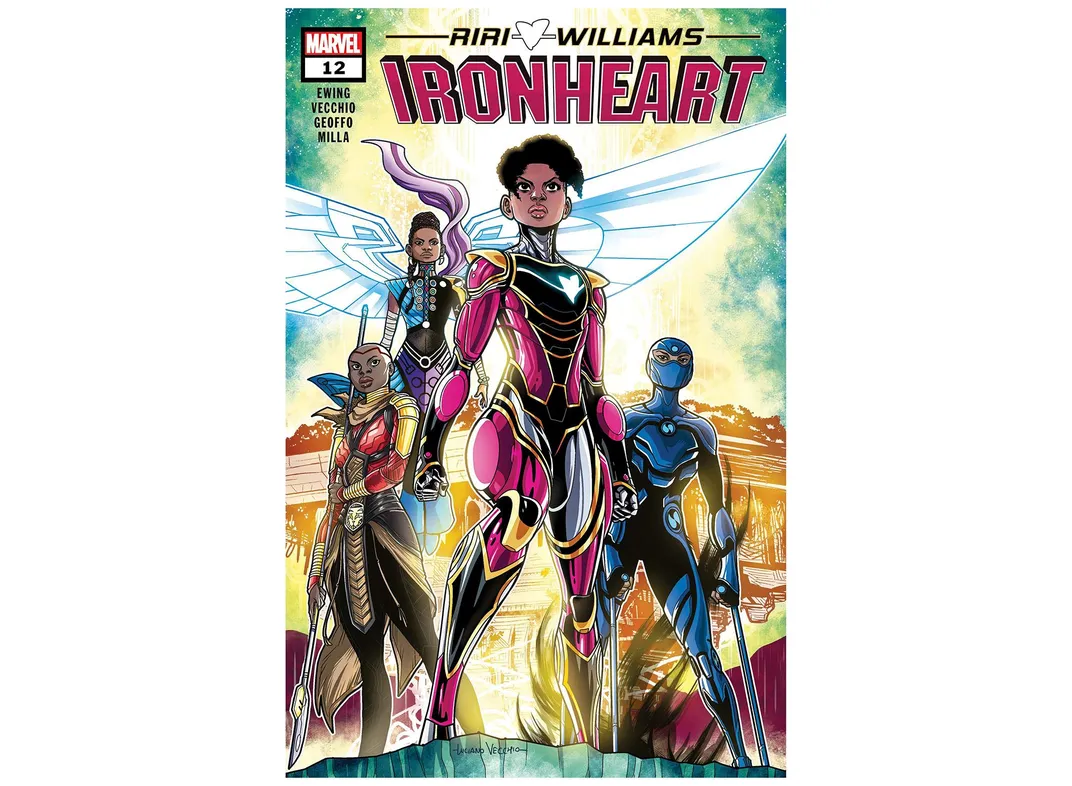

This tradition of representation and black storytelling continues. Riri Williams, a young black woman who dons a version of Iron Man’s armor to become Ironheart, was a 2016 creation by Brian Michael Bendis, who is white. But in 2018, she was reimagined by Eve Ewing, an assistant professor at the University of Chicago and a black woman. Ewing’s Ironheart was a much-praised take on the character, which, in the words of one reviewer, “perfectly walks the line between classically Marvel and refreshingly new.” Today’s black artists—and the superheroes they boldly create—are standing on the shoulders of Black Panther.