How Business Executive Madam C. J. Walker Became a Powerful Influencer of the Early 20th Century

A tin of hair conditioner in the Smithsonian collections reveals a story of the entrepreneurial and philanthropic success of a former washerwoman

:focal(1442x842:1443x843)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/19/1b/191b8d28-be6b-4b02-8785-1e0b9dd434bf/2009_9_2_003.jpg)

For Madam C.J. Walker, a new life began when she decided to find a cure for her own hair loss. Her ailment would become the impetus for a large, multi-faceted, international company that sold hair care products—including an inventive vegetable shampoo that she developed—and that offered training to women both as hair stylists and as sales representatives.

Madam Walker, the daughter of former enslaved laborers in Louisiana, “created educational opportunities for thousands of black women and provided them jobs and careers, and opportunity to make money, and to make money in their own community,” says Nancy Davis, curator emeritus at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C., where Walker’s business is featured in the museum’s “American Enterprise” exhibition.

No one could have foreseen Walker’s stunning success as an early 20th-century entrepreneur or her remarkable legacy in philanthropy and black activism. “I think her legacy, as well, is about pride in self as well as economic independence, which is something that she was able to establish not just for herself, but for all the women she educated through her program and became their own agent,” says Michèle Gates Moresi, supervisory museum curator of collections at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. By the end of Walker’s life in 1919, she would rank among the nation’s wealthiest self-made women of the era.

Tragedy and adversity dominated her early years. She was born in 1867 as Sarah Breedlove, just four years after the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation. Her father was a farm laborer; her mother, a laundress. As a child, she worked in the cottonfields, but by the age of 7, she had suffered the loss of both of her parents and was forced to join the household of her sister and a brother-in-law, who moved with her to Vicksburg, Mississippi. To escape the cruelties she endured in her brother-in-law’s home, she married at age 14. But six years later, she was a widow with a 2-year-old daughter in a world that seemed destined to lock her into a life of poverty.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/48/95/48953421-138c-4270-a4b9-77ece26d682d/2013_153_8_001.jpg)

To begin anew, she moved to St. Louis, where her four brothers worked as barbers. With no formal education, she labored the next 18 years as a washerwoman, often earning as little as $1.50 per day. In the 1890s, she began to notice places on her scalp where she was losing her hair. Bald spots were not rare among women of that time, particularly in areas without running water and electricity. Many women made a habit of washing their hair only once a month, and their scalps suffered, thus making it difficult for hair to grow.

Walker, then in her mid-20s, told others that she prayed for a way to heal her bald spots, and in a dream, she said, “a big, black man appeared to me and told me what to mix for my hair.” She experimented with formulas and settled on a new regimen of washing her hair more often and using a formula that combined a petroleum jelly-like balm, beeswax, copper sulfate, sulfur and perfume to hide the sulfur smell.

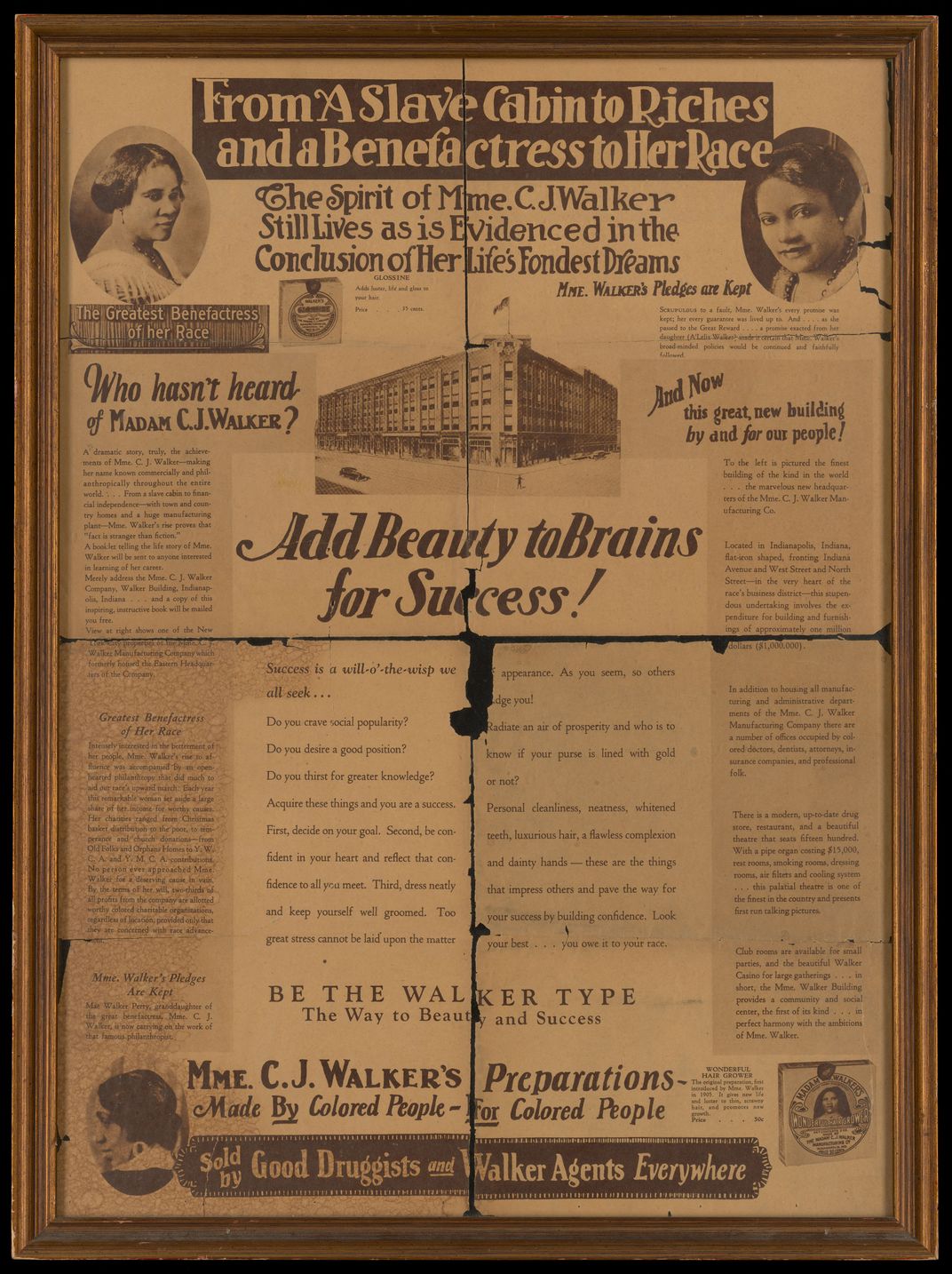

The National Museum of African American History and Culture holds in its vast collections a two-ounce canister of Madam C. J. Walker’s Wonderful Hair Grower, her top-selling product, donated by collectors Dawn Simon Spears and Alvin Spears, Sr. Several other items, gifts of her great great-granddaughter and biographer, A’Lelia Bundles, include advertisements, beauty textbooks and photographs. On the lid of the two-ounce can appears an African-American woman with thick, flowing hair. That woman was Walker herself.

Her success “clearly took a special kind of genius and determination,” says Bundles, author of On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker, soon to be made into a Netflix series starring Octavia Spencer. The formula that she had created healed her scalp and when her hair began to sprout, “she became her own walking advertisement,” Bundles says.

On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C.J. Walker

On Her Own Ground is not only the first comprehensive biography of one of recent history's most amazing entrepreneurs and philanthropists, it is about a woman who is truly an African American icon. Drawn from more than two decades of exhaustive research, the book is enriched by the author's exclusive access to personal letters, records and never-before-seen photographs from the family collection.

Walker started her business by selling her formula door-to-door. Because of a growing urban black population after the turn of the century, “she was going after African-American women,” Bundles says. “She knew that this market was untapped.”

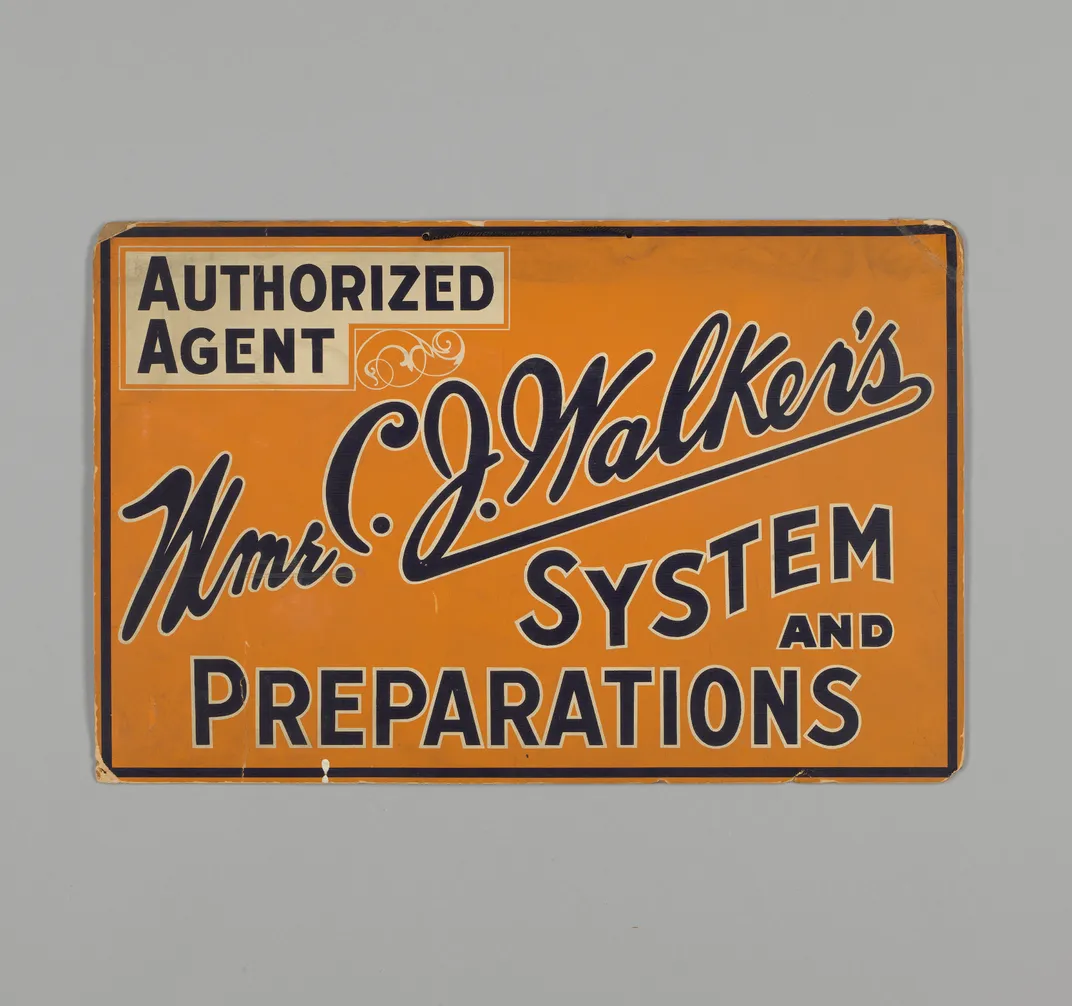

In 1905, Walker moved to Denver as an agent for Annie Turnbo Malone, another successful African-American businesswoman. There, she married journalist Charles J. Walker and used her married name on her products. Businesswomen of her era often adopted “Madam” as part of their work-life persona. The Walkers traveled the South selling the “Walker Method.” She advertised in black newspapers nationwide, and by awarding franchises and accepting mail orders, Madam Walker soon extended her geographic reach across a nation where segregation often made travel difficult for African-American women. She moved next to Indianapolis in 1910 and there, built a factory, a beauty school and a salon. Not satisfied with conducting business in the United States alone, she took her products in 1913 to Central America and the Caribbean, and while she was out of the country, her daughter Lelia, who later became the Harlem Renaissance socialite known as A’Lelia Walker, moved into their newly built upscale Harlem townhouse, where she opened the elegant Walker Salon. Madam Walker joined her daughter in New York in 1916.

Walker later lived in a mansion in Irvington, New York. Her neighbors were such noteworthy tycoons as J.D. Rockefeller and Jay Gould. But she hadn’t lost sight of her earlier hardships. She was quick to help the poor and to position herself as an activist, championing black rights. And she was quite formidable. Once, she even faced off against a stubborn Booker T. Washington, founder of the Tuskegee Institute, not backing down after he blocked her from speaking at the National Negro Business League.

Three other male cosmetics entrepreneurs had opportunities to speak, but Walker did not. Clearly out of patience by the conference’s last day, Walker stood up, interrupting the scheduled events, to address the snub: “Surely, you are not going to shut the door in my face. I feel that I am in business that is a credit to the womanhood of our race.” She went on to talk about her company’s widespread success. “I have built my own factory on my own ground,” she said. Washington showed no reaction to her speech, but the following year, she was a scheduled speaker at the annual meeting.

By now, she was a force to be reckoned with in early 20th-century America. “I was really touched about her engagement in philanthropy,” Moresi says, “because it wasn’t just that she went to the NAACP and she was so supportive and generous. As a business person, with resources she was setting an example for other businesses and people with resources to be that engaged. I know that she encouraged her agents at [sales] conventions to be engaged as well.”

As her business grew, her philanthropic and political activism also surged. Shortly after arriving in Indianapolis, her $1,000 gift to the African-American YMCA garnered attention in African-American newspapers across the country. Such a generous gift (about $26,000 in today’s dollars) from an African-American woman was met with both surprise and delight. Uneducated herself, Madam Walker made the support of African-American secondary schools and colleges, a prominent part of her generous donations, particularly in the South.

She also became active in social service organizations, and to promote equal rights, she worked with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the National Conference on Lynching.

In 1917, Walker and other Harlem leaders went to the White House to convince President Woodrow Wilson that African-American service in World War I should guarantee federal support for equal rights. Among other things, the group specifically wanted to have lynchings and white mob violence classified as federal crimes. They had been promised an audience with the president at noon on August 1, 1917. However, at the last minute, they were informed that Wilson was too busy to see them. Their leader, James Weldon Johnson told Joseph Patrick Tumulty, Wilson’s secretary, that his group represented the “colored people of greater New York,” and presented him with a document stating that no white man or woman had been convicted in the lynchings of 2,867 African Americans since 1885. After hearing Tumulty’s weak assurances that the president shared their concerns, the delegation turned its attention to Capitol Hill, where some lawmakers promised to file the anti-lynching appeal in the Congressional Record and to call for probes of recent racial attacks. Walker and the other Harlem leaders faced a shocking realization that neither eloquence nor wealth could convince Wilson to meet with them. This was a great disappointment in a life marked by tremendous successes and equally crushing tragedies. “I think her experience speaks to a lot of aspects of the African-American experience that people need to know about and not just think about her as a lady, who made a lot of money,” Moresi argues.

Many of the women educated and employed by Walker became supporters of the Civil Rights movement, too, says the Smithsonian’s Nancy Davis. “Because black beauty parlor owners had their own clientele, they weren’t beholden to white consumers, and they were able to make their own money.”

Walker cared deeply about social issues, but she was devoted to her business as well. As she moved around the U.S., Walker trained African-American women as “Walker agents” in her company. “I had to make my own living and my own opportunity,” she told them. “Don’t sit down and wait for the opportunities to come. Get up and make them.” By the end of her life, just a short dozen years after Madam C.J. Walker products had begun to be marketed aggressively and successfully, she had created ten products and had a force of 20,000 saleswomen promoting her philosophy of “cleanliness and loveliness.”

Financial success allowed Madam Walker to shatter societal norms and live in a mansion designed by an African-American architect, Vertner W. Tandy, in a wealthy New York City suburb. Her home, Villa Lewaro, is now a National Historic Landmark. It has undergone restoration but remains in private hands. Walker is considered the first African-American female millionaire. Her personal fortune was estimated to be $600,000 to $700,000 when she died in 1919 at the age of 51, but ownership of the company added significantly to that figure. Two years earlier, she had denied reports that she was a millionaire, saying, “but I hope to be.” Her Madam C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company was sold by the Walker estate trustees in 1986, 67 years after her death.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)