How Change Happens: The 1863 Emancipation Proclamation and the 1963 March on Washington

At the 150th and 50th anniversary of two historic moments, the African American History and Culture Museum and American History Museum team up

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20121214104030March-Thumb.jpg)

In the midst of the Civil War, between writing the first and final drafts of the Emancipation Proclamation, Abraham Lincoln stated, “If I could save the Union without freeing any slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it.” On January 1, 1863, the final version was issued as an order to the armed forces. One hundred years later on a hot summer day, hundreds of thousands of individuals marched on Washington to demand equal treatment for African Americans under the law.

The year 2013 marks the 150th and 100th anniversaries of these two pivotal moments in American history and in recognition a new exhibition opens December 14, “Changing America: The Emancipation Proclamation, 1863 and the March on Washington, 1963,” produced jointly by the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) and the National Museum of American History (NMAH). Lonnie Bunch, NMAAHC director says he, along with NMAH curators Harry Rubenstein and Nancy Bercaw, chose to pair the anniversaries not just because the March on Washington was seen as a call to finally fulfill the promise of the Proclamation, but because together they offer insights into how people create change and push their leaders to evolve.

For example, says Bunch, “It isn’t simply Lincoln freeing the slaves. . . there are millions of people, many African Americans, who through the process of self-emancipation or running away, forced the federal government to create policies which lead to the Emancipation Proclamation.”

In the same way the March on Washington put pressure on John F. Kennedy to draft the Civil Rights Act of 1964, so too did the actions of abolitionists and enslaved people force Lincoln’s government to respond.

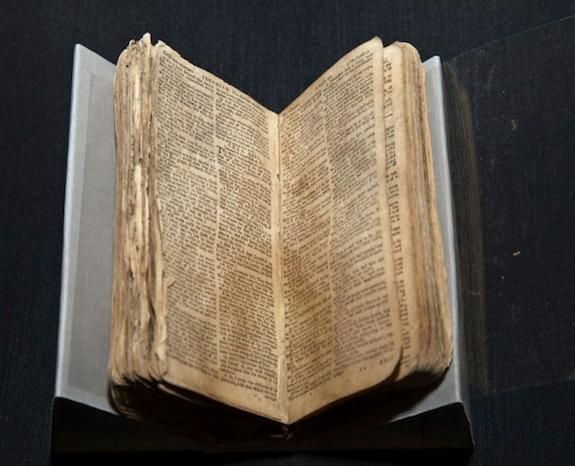

Artifacts like Nat Turner’s bible, Harriet Tubman’s shawl and a portrait of a black Union soldier and his family together with Lincoln’s proclamation tell stories of self-emancipation before and during the war.

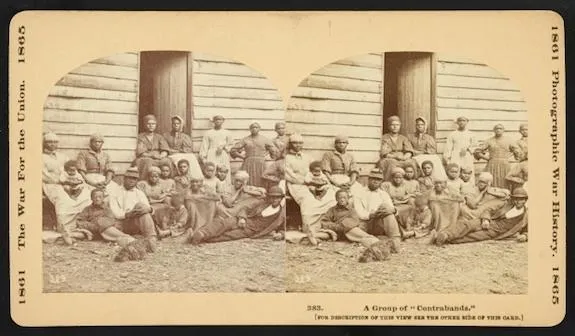

Slaves, who had run away and established the so-called freedmen’s villages, were demanding to be allowed to fight with the Union, even as they were initially considered “contraband of war.” The presence of their huge tent cities—in Memphis an estimated 100,000 rallied— established along the Mississippi River, the East coast and in Washington, D.C., served as a constant reminder, a silent daily witness, to the president. “They were pushing the war toward freedom,” says Bercaw.

Bunch says the curatorial team worked with Civil Rights legends, like Representative John Lewis, to understand how the March was organized from within. Highlighting the role of women in the numerous civil rights organizations that helped orchestrate the event, the exhibit again models the diverse roots of change.

“When I look at this moment,” says Bunch, “it should really inspire us to recognize that change is possible and profound change is possible.”

”Changing America: Emancipation Proclamation, 1863 and the March on Washington, 1963″ runs through September 15, 2013 at the American History Museum.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)