How Cherry Trees Blossomed Into a Tourist Attraction

The fragile and transient blossom may herald the first stirrings of spring, but their significance has evolved since the 9th century

Before the redbuds, before the azaleas, before the lilacs, there is the fleeting blossoming of the cherry trees, heralding the end of winter. Washington D.C. has celebrated that event with the Cherry Blossom Festival each year since 1935. The tradition has its origins in a gift of 3,020 cherry trees from the mayor of Tokyo in 1912. At the time, Japan considered the cherry tree to be a symbol of celebration and an appropriate gift to a potential ally that would represent the best of Japanese culture and art. But the significance of the cherry blossom is highly nuanced and a closer look reveals a complex history.

James Ulak, Smithsonian's senior curator of Japanese Art at the Freer and Sackler Galleries, says that the meaning of the cherry blossom in works of art has evolved over time.

“The cherry tree is long associated with Buddhist notions of change and transformation. So if you walk out on the Tidal Basin today you'll see these blossoms and then they drop. So this notion that you have this bust of blooms and then they pass, this is a Buddhist notion. There have always been these overtones of melancholy. And you see this in poetry in the early and medieval periods,” says Ulak. From the 9th century onward, the cherry blossom was a subtle symbol of the circle of life and death.

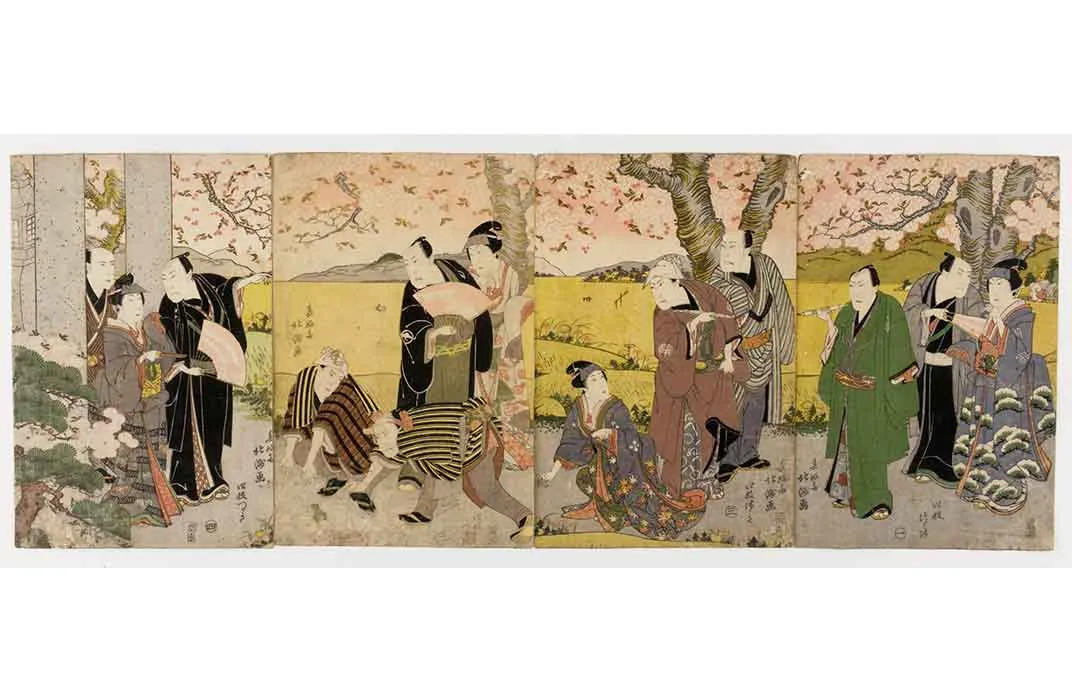

Beginning in the 17th century, Japanese attitudes about the cherry blossom began to change. “Gathering under the cherry trees becomes more of a happy carousing than a reflective component,” says Ulak.

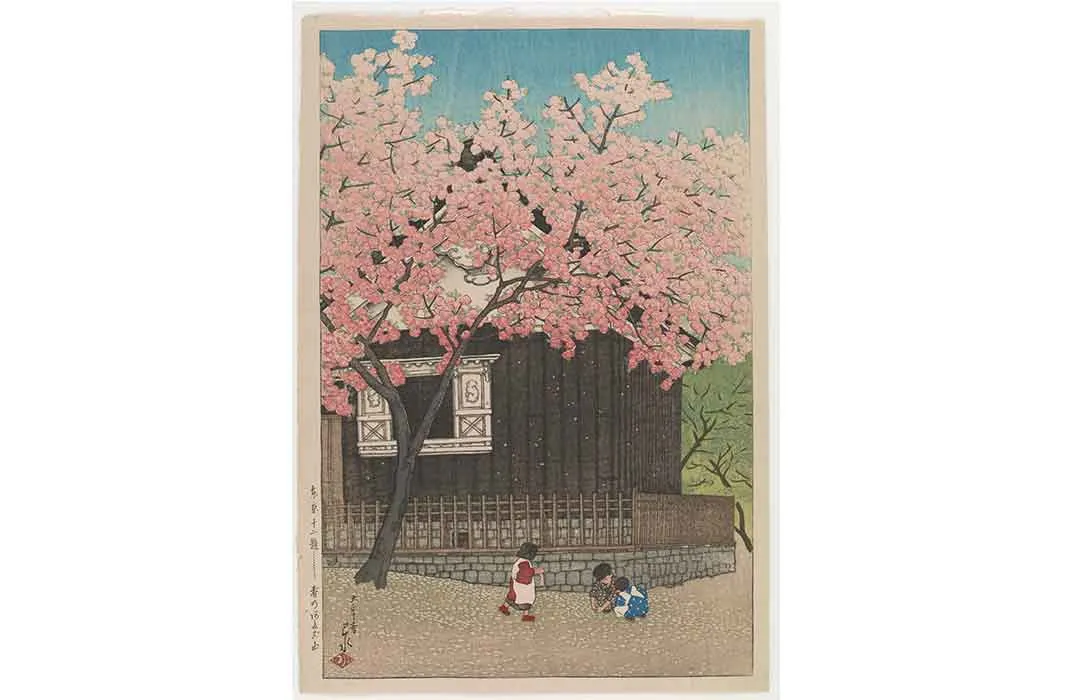

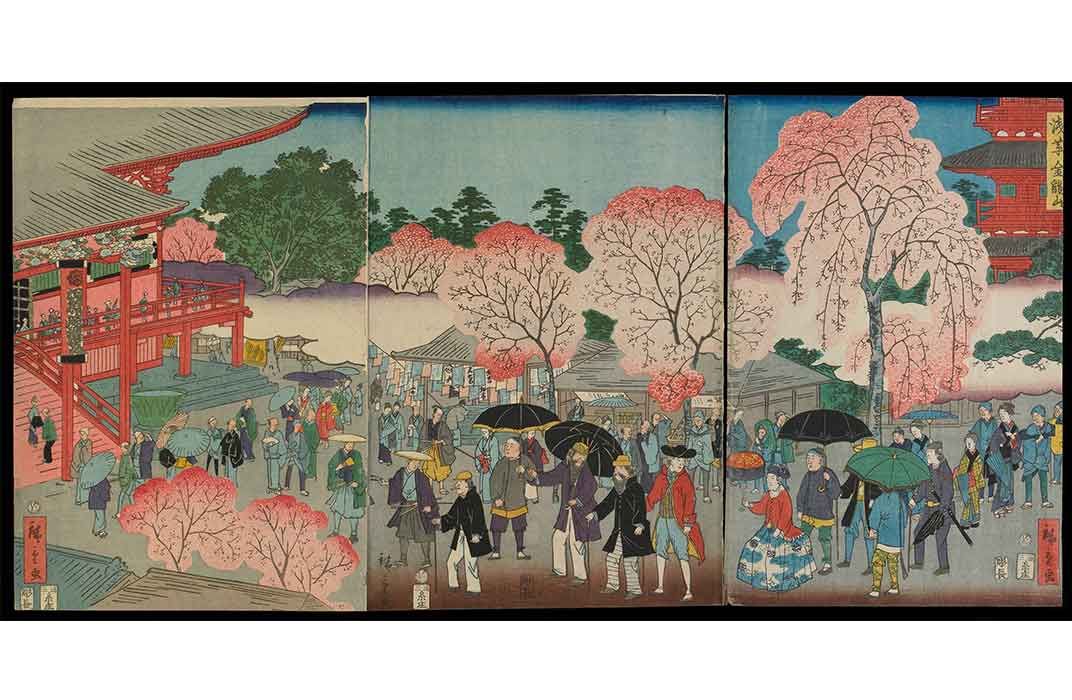

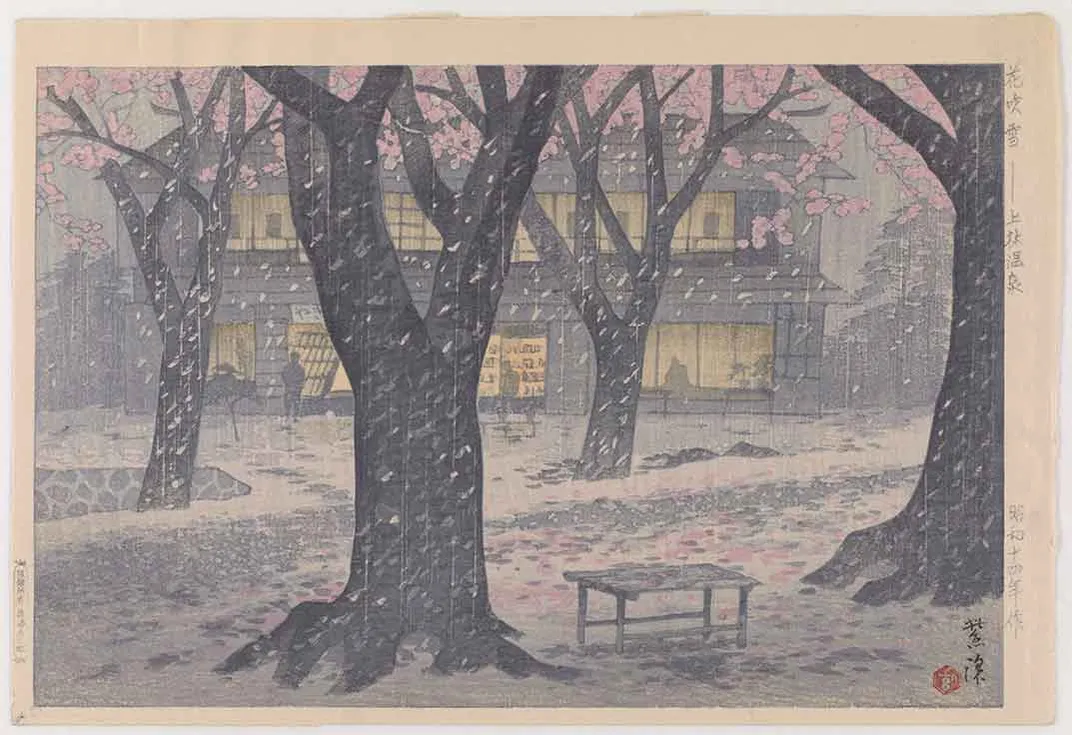

The earliest precursors of D.C.'s festival began to take place. Japanese prints like the 1861 Buddhist Temple Asakusa Kinryuzan by Utagawa Hiroshige II of the Edo period depict tourists celebrating and carrying umbrellas beneath the blossoms at the Kobayashi Hot Spring. “It is one step away from a travel poster in my opinion. . . The affectation is that instead of snow, it's a snow of cherry blossoms falling.”

“In the 19th century the tree becomes a nationalistic symbol. Of the soldiers fighting and dying against the Chinese or the Russians,” Ulak says.

The war fought from 1904 to 1905 between Russia and Japan directly led to D.C.'s cherry blossom festival and to the introduction of Japanese ornamental cherry trees to the United States. The war was concluded with a treaty mediated by the administration of President Theodore Roosevelt.

His Secretary of War, William Howard Taft, was an important part of negotiating that treaty and other agreements between the U.S. and Japan that came out of the treaty process. This history made Taft very popular in Japan. Taft had personally met the mayor of Tokyo and the Emperor and Empress of Japan. When Taft became President, this personal history led the mayor of Tokyo to offer a gift of thousands of cherry trees to America's capital city.

The trees became a symbol of what seemed to be a strong relationship between Japan and the U.S. But by 1935, when the first cherry blossom festival was held, Japan's international status was already on shaky ground.

On the occasion of the first festival, famed Japanese print-maker Kawase Hasui was asked to produce a commemorative print showing blooming cherry trees with the Washington Monument in the background. “In my opinion it's kind of an ugly print, but people love it,” says Ulak. “1935, you are right in that period where the world is going to hell in a hand basket. And Japan is really trying to use art around the world to smooth things over. It was this idea of the rest of the world seeing Japan's sophistication. And at the same time, they are chewing up Manchuria. I suspect that Hasui and others played into that, wittingly or unwittingly.”

After the attack on Pearl Harbor in December of 1941, all things Japanese were suddenly suspect in the United States. Vandals chopped down four of Washingon, DC's Japanese cherry trees. The Smithsonian's Freer Gallery, home of America's premier collection of Japanese art, removed all of it from public display out of fear that it, too, would be vandalized.

“Of course by World War II, the kamikaze pilots spiraling down from the sky with their flames trailing are supposed to be like cherry blossoms falling from the tree,” says Ulak. “Every generation has customized the flower to their particular meanings and interests.”

The cherry tree festival managed to survive the war and the old cultural ties reasserted themselves quickly. By 1952, major traveling collections of Japanese art began coming back to American museums.

“All of Japan is one big cherry blossom festival now,” says Ulak. “The whole country gets excited about it. On the evening news they follow the line of blooming from east to west. . . But it was not always seen as such a lighthearted burst of spring... It's a phenomenon of the last hundred years, at best.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JacksonLanders.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/51/a4/51a42202-a398-4735-81cc-e5563a0c48c8/s1998159web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/62/6d/626d507a-8ea6-4b36-bf9e-0ab4f2af3d97/s200382117web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JacksonLanders.jpg)