How Do Astronauts Go to the Bathroom in Space?

A look at the space shuttle toilet and “the deepest, darkest secret about space flight”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/toilet-space-around-the-mall.jpg)

The National Air and Space Museum has a $50,000 toilet. It’s functional, and it answers one of the greatest engineering puzzles of the 20th century: How do you pee in space?

The “space toilet” is a replica of the waste collection systems used aboard NASA’s five space shuttles—Atlantis, Challenger, Columbia, Discovery and Endeavor—which launched into space on 135 missions between 1981 and 2011. Missions often lasted longer than 10 days, so astronauts needed a reliable way of relieving themselves while floating around and doing research. How they managed to go is the most common question astronauts are asked, says Mike Mullane, a veteran of three space shuttle missions and author of Do Your Ears Pop in Space and 500 Other Surprising Questions about Space Travel. It’s also one of the most frequent questions heard from visitors to “Moving Beyond Earth,” the exhibition that features the replica space toilet in a full-scale model of a space shuttle’s living quarters.

The subject is so popular, says museum staffer Michael Hulslander, because “it is truly universal.” The first thing he thought when planning the exhibition was “oh my god, we need a toilet.”

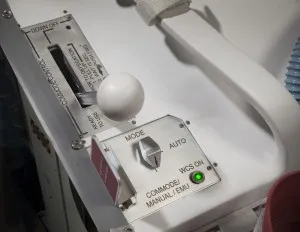

The space toilet doesn’t look all that different from the Earth-bound toilet in your home bathroom (its base is larger, its bowl is smaller and it has an elephant trunk-like tube—for context, look past the right chair in this image of Discovery’s middeck), but months of research and testing go into each model to ensure it runs maintenance-free for the duration of a mission. And research costs add up: the price tag on the actual space shuttle toilet that flew on Endeavor? About $30 million.

Each shuttle had only one toilet, so “they had to work,” says Hulslander. (And they did, mostly.)

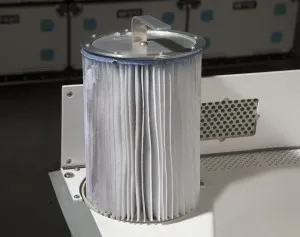

While the more recent space toilet models used on the International Space Station do more and cost less than those aboard NASA’s shuttles (these range in the ball park of $19 million; one even purifies urine into potable water), all space toilets rely on the same basic system to remove waste: differential air pressure. Liquid waste is sucked into a plastic funnel on the end of the trunk-like tube and deposited into the base’s urine container, which vents into space when filled. Outside, the urine sublimates and eventually turns into gas. Solid waste goes straight into the bowl, Earth-style, where it is stored for the remainder of the flight. Jettisoning solid waste would ”just be bad for business,” Hulslander says, because it would send a projectile hurtling 17,500 m.p.h. through space—unlikely to hit anything, but better safe than sorry.

When using the liquid waste tube, female astronauts tend to have an easier time with funnels than male crewmembers, because female funnels are cup-shaped and adhere to the body when the toilet’s pressure is turned on. Men, meanwhile, use a small cone, which they must hold close enough to themselves to collect waste, but not so close that they get vacuumed in. “We do not want men docking,” cautions Scott Weinstein, a crew habitability trainer at NASA, in a video on space toilet training.

For solid waste deposits, the toilet has foot straps and thigh braces to help astronauts stay in place, and air-tight bags on hand for toilet paper disposal. Astronauts spend a lot of time in training sitting on space toilets to learn how to create a strong seal and how to align themselves properly. In Houston, the Johnson Space Center has a bathroom with two space toilets for practice. One model is fully functional. The other, a “positional trainer,” has a video camera beneath its rim, and a television monitor on a table in front of it. Astronaut Mike Massimino calls this second toilet “the deepest, darkest secret about space flight” in the training video.

“This takes a lot of glamour out of the business when you go for training,” Mullane says about his first encounter with the positional trainer.

Astronaut Tom Jones, another seasoned space veteran, spent 52 days in orbit on four space missions. He says that while “everybody laughs” at training, “you realize that you can’t hold it for 18 days. You’ve got to be able to use the system. And you want to be efficient at it, because it takes time away from what you really should be doing.”

Jones never lost a sense of novelty using the space shuttle toilet, though, even with its steep learning curve. On his third trip into space, aboard Columbia, he remembers glancing at the privacy curtain that covered the shuttle’s toilet and often seeing socks where a head should have been. His crewmate Story Musgrave enjoyed peeing upside down. “Don’t just use the bathroom like you would on the ground. Take advantage of being weightless and try out some new things,” Musgrave would remind him.

“I never got bored,” Jones says. “You go about these things with a smile on your face thinking this is amazing. This is really strange and really wild.”

Astronauts also used the toilet’s closed-off space on the shuttles for changing clothes and wiping themselves down with bath towels. On Jones’ missions, crewmembers stored their towels in grommets along the toilet’s wall; in the absence of gravity, the towels’ ends floated straight out into the small compartment like kelp in the sea. When Jones had to go, he would float through this mini towel kelp forest to the shuttle’s hatch window next to the compartment, fasten the curtain behind him and stare into the cosmos as he relieved himself into a $30 million vacuum cleaner.

“It’s a pretty neat bathroom,” he says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/paul-bisceglio-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/paul-bisceglio-240.jpg)