How Do You Build a 12-Ton Sculpture Installation? Very Slowly

Two years, two births, one Olympic Games and one global crisis–a lot can happen in one art project.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Phoenix.5_Thumb.jpg)

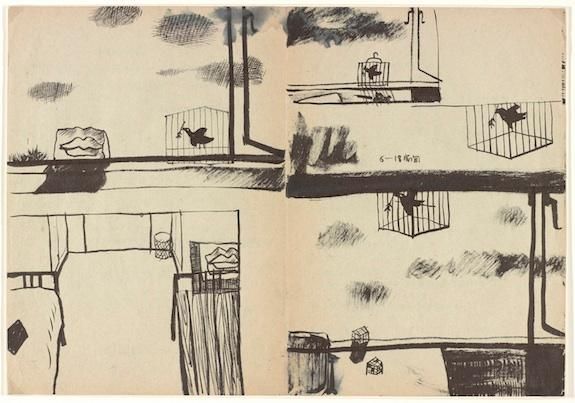

When you go to the museum for a show, what you see is the final product: a painting, a photograph, an installation. But now at the Sackler, you can see the process behind the product in the new exhibit “Nine Deaths, Two Births: Xu Bing’s Phoenix Project.” The exhibit explores the two-year effort to complete Chinese contemporary artist Xu Bing’s “Phoenix Project” and offers a look into the ways both creation and destruction can be part of the artistic process.

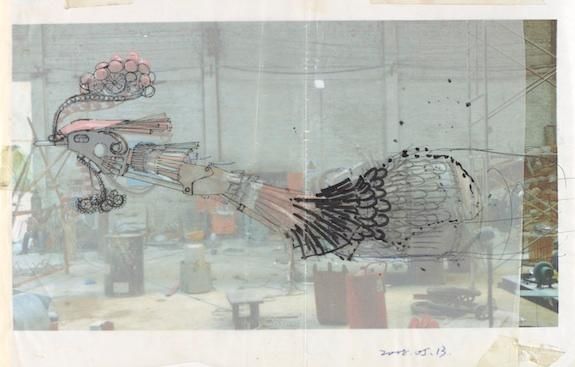

Now on view at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art, the final product, two giant phoenix sculptures, were originally commissioned in 2008 and intended for a building in the heart of Beijing’s central business district. But after delays for the Olympics, a global financial crisis and funding issues, the installation found different sponsors and a new home. At 12 tons and nearly 100 feet in length, the sculptures need lots of space. Mass MoCA had the room and desire to display it and the Sackler decided to offer its companion exhibit having worked with Xu in 2001 for his show “Word Play,” when it also acquired the iconic ”Monkeys Grasping For the Moon” sculpture.

The phoenixes reference the traditional Chinese motif but rendered from construction site materials, take on a new and modern meaning in the saga of China’s economic development. “My two phoenixes are quite different,” says Xu. While traditional lacquers, paintings and even hair ornaments from China (some of which are on view as part of the exhibition) draw on the mythical bird as a symbol of wealth, nobility and peace, Xu’s industrial installation is in tension with these qualities.

When Xu went to the site where his sculptures were originally going to be and saw the construction of the new building in Beijing, he says he came in contact with the conditions of the workers there. He saw before him the face of Chinese development–its soaring architectural business buildings–and the hands–the laborers who did not seem to reap the benefits of the country’s boom. “The contrast was the inspiration,” he says.

Because of the scale of his project, he had to rely on the same labor. He relied on their know-how and expertise when designing and modifying his work. He also spoke with engineers and architects to help design the massive birds.

But, in the lead up the Olympics, he, along with everyone else engaged in construction, was ordered to stop. The government wanted to ensure pristine air quality for the international games so as not to draw any criticism. It’s an irony not lost on Xu, who included official government notices in the exhibit at the Sackler. After the financial crisis, he then had to find alternative funding and ended up turning to Taiwanese-based businessman, Barry Lam, founder of Quanta Computer.

Citing the many ups and downs of the artistic process, curator Carol Huh says, “What we’ve tried to do here for the first time is really show the process.” Sketches, clay models, computer-generated renderings as well as a special documentary about the works comprise the exhibit. The title, nine deaths and two births, refers to the many challenges he faced and the two children born to his staff during the process, a symbol of the phoenix-like quality of artistic creation.

On view at Mass MoCA until November, the phoenixes will head next to New York City’s Cathedral of St. John the Divine.

“Nine Deaths, Two Births: Xu Bing’s Phoenix Project” is on view through September 1, 2013.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)