How a Five-Letter Word Built a 104-Year-Old Company

THINK—printed on signs, deskplates, business cards and notepads—was the seed from which the rest of IBM’s culture would grow

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f5/b2/f5b278b1-be71-4db4-9f3e-81248333356f/p120thinket201441384web.jpg)

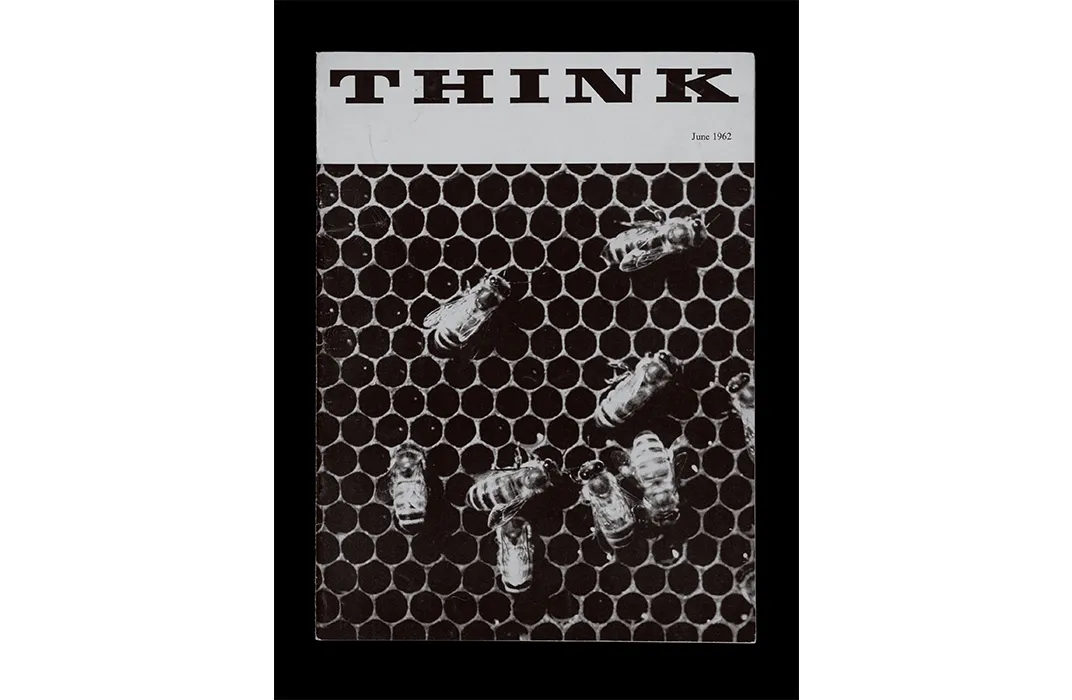

Last year, the daughter of an executive at J. Schoeneman Inc., one of the first garment manufacturers to buy an IBM computer, donated a seemingly modest item to the Smithsonian National Museum of American History: a 4.5-by-3-inch paper notepad with the word THINK embossed on its leather cover.

Small enough to fit into the breast pocket of a dress shirt, the notepad, according to Smithsonian curator Peter Liebhold, was a gift to the executive from his IBM salesman. This would have been in the 1960s, Liebhold says, when all IBM employees carried THINK notepads and business cards and worked beneath THINK signs.

The campaign was parodied in MAD Magazine, the subject of New Yorker and Look cartoons, and IBM was “deluged with requests from the public” for THINK paraphernalia, according to company archives. By 1960, IBM was distributing “about 250,000” THINK notepads annually to non-IBMers like the Schoeneman executive. THINK fascinated people because its pervasiveness represented something so new: a consciously created company culture.

“IBM had a symbol—a symbol important to the culture in the way that the Eiffel Tower is important to France or the kangaroo to Australia. That symbol was the word THINK,” wrote Kevin Maney in his highly acclaimed biography of Thomas Watson, Sr., The Maverick and His Machine.

The motto originated with Watson, a six-foot-two self-made man with a prominent chin, fiery temper and abundant charm, who was hired as general manager of IBM in 1914 and soon became its president. The culture Watson created at IBM was, according to Maney, “a whole new species—a great evolutionary leap from what had come before.”

Starting out, he didn’t have much to work with. “He inherited a piece of shit, basically,” says Maney. In 1914, IBM was called C-T-R, or Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company, a loose-knit conglomeration of manufacturers, their operations as awkward as their name. Watson, meanwhile, had just barely escaped a prison sentence for unfair business practices at National Cash Registers (at his former boss’s request, he’d started a fake secondhand cash register company to put real ones out of business). C-T-R was his chance to make good, and he began with THINK.

Watson had actually coined the slogan at National Cash Registers (NCR) in 1911. “The trouble with every one of us is that we don’t think enough!” he shouted in a sales meeting, scrawling the word THINK across a chalkboard. With permission from his boss, John Patterson, he had THINK signs made and hung in the office. When Watson left NCR, he took THINK with him, along with management strategies gleaned from Patterson, one of the earliest company presidents to establish sales training and incentives programs.

Watson got the idea that a company could have culture from Patterson, according to Maney. “But,” adds Maney, “NCR, like most companies at the time, had a culture built around an individual. Companies shaped themselves to their leaders. Watson seemed conscious of the idea that it had to be bigger than him, so he created culture in a more systematic and personal way.” Smithsonian curator Kathleen Franz expands on THINK’s role in Watson’s company culture: “Whereas other companies made culture in a paternal way, IBM was about motivation: think for yourself, think for your company, come up with something new.”

THINK—printed on signs, deskplates, business cards and notepads—was the seed from which the rest of IBM’s culture would grow. Watson also created incentive programs, like the Hundred Percent Club for salesmen who exceeded their quotas, and training programs (he would eventually open an IBM “schoolhouse” in Endicott, New Jersey). Early employees added their own touches to the developing culture, which included copying the boss’ attire (Watson didn’t originally mandate IBM’s dark-suit-white-shirt dress code, says Maney, but he liked it) and writing songs about the company, like IBM’s rally song “Ever Onward,” which were sung at group functions. “Watson was the progenitor of the IBM culture,” explains William Klepper, a professor of management and director of executive education at Columbia Business School. “But it took IBMers to bring it to full life.”

IBMers officially became IBMers in 1924, when Watson changed the name of the company to International Business Machines. Soon after, he began offering benefits to his factory employees, including insurance, vacation and a company golf course, which simultaneously widened IBM’s culture and kept unions away by keeping employees happy. He could afford this because the company was doing well, in part due to Watson’s decision to focus on developing punch card technology (which became so widely used that punch cards were called “IBM cards”), in part because of the booming twenties economy, and in part because of IBM’s growing culture, which, according to Maney, “wove together the pieces of the business and drove employees forward in ways that competitors couldn’t beat.”

At the time, the concept of company culture was in its infancy, and IBM’s THINK slogan and company rally song seemed as exciting and fresh as ping-pong tables and hoodies did at the dawn of today’s start-up culture. “In the twenties, IBM was like Uber,” says Maney. “It was this hot tech company, small but growing fast, with this dynamic leader. Later on, Watson had this image of being a corporate stiff, but in his early years he was a real risk-taker.”

One such risk was his decision not to lay anyone off during the Great Depression. It was a bold move for a midsize company—even industrial giant Ford Motor Company had layoffs—but it paid off in the mid-thirties, when IBM won a commission to equip the newly formed Social Security Administration. This “catapulted IBM from a midsize corporation to the global leader in information technology” according to IBM’s archives. Revenues increased more than 81percent, and job security became one of the fundamental components of IBM culture.

“IBM called it the full employment policy, and it was central,” says Quinn Mills, a professor of business administration at Harvard and co-author of Broken Promises: An Unconventional View of What Went Wrong at IBM. In his book, Mills argues that IBM’s eventual fall from the top of the tech industry in the eighties was made far worse by layoffs. “Full employment was an expression of culture,” says Mills, “and the culture attracted people who wanted stability. Losing that was a betrayal.”

Not that the culture was ever perfect. “They never hired executives from outside,” says Mills, “which led to leaders who all saw the world in the same way. When it changed dramatically, none of them could see it.” This had nearly happened before: through training, explains Maney, “nonbelievers were sifted out,” and nobody challenged Watson’s belief that punch cards were their core business, even as they began to grow obsolete. In 1956, the year Watson died at age 82, Fortune journalist William Whyte published The Organization Man, a highly acclaimed management book that includes a damning quote from an anonymous IBM executive: “The training makes our men interchangeable.”

As IBM’s new president, Watson’s son, Thomas Watson, Jr., could have scrapped the culture and started over. But despite its flaws, the company culture was still strong enough to “drive IBM,” in Maney’s words, so Watson, Jr. instead chose to reinvigorate it with the same symbol his father used to create it. “‘Think it through,’” he advised, “is a reminder that creative, individual thinking is an indispensable tool.” He called for more “wild ducks,” urging his employees not to “let anyone talk you into being the safe company man.” In 1964, IBM produced the System 360, a revolutionary product that Maney calls “IBM’s iPhone,” which launched the company to the forefront of the computer industry. By 1983, they still dominated the industry to the degree that a young Steve Jobs declared war against an “IBM-dominated and controlled future.”

When IBM ran into business trouble again in the mid-'80s, the results weren’t nearly so positive. “It was one of the biggest business fails in American history,” says Mills. But once again, it was company culture that kept the company afloat. In 1993, Lou Gerstner was the first CEO since Watson, Sr. to be hired from outside the company. “Many of us, including me, were extremely skeptical about this outsider CEO with no technical knowledge,” says Lee Nackman, who worked at IBM as a researcher then product development executive from 1982 to 2008. “We were wrong about what was important: He changed the culture to focus on the customer and this enabled the turnaround in the company. Culture was everything.”

In 2011, IBM, one of the oldest tech companies in the world, celebrated its centennial with an exhibit and app called THINK. Meanwhile, at the Smithsonian, curator Kathleen Franz muses over the notepad in the collections: “It tells such a great story about American business,” she says. “And it fits in the palm of your hand.”

The new permanent exhibition “American Enterprise,” opened July 1 at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. and traces the development of the United States from a small dependent agricultural nation to one of the world's largest economies.

The Maverick and His Machine: Thomas Watson, Sr. and the Making of IBM

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/marymann.jpg)