How Gen. Henry ‘Hap’ Arnold, the Architect of American Air Power, Overcame His Fear of Flying

Despite his phobia, the five-star general built the U.S. Air Force

:focal(1272x845:1273x846)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4d/ab/4daba06f-0d96-4184-95ce-6a3c911b6c31/hapgettylead.jpg)

The two young Army lieutenants had spent the night in Duxbury, Mass., after being forced to land their seaplane in Plymouth Bay because of high winds. The next day, August 12, 1912, the aviators prepared to resume their flight from Marblehead on Massachusetts’ North Shore to an Army base on the Housatonic River in Connecticut.

At first, the Burgess Model H—one of the first planes designed and built for military use—handled well as it skimmed the water during takeoff. However, as the hydroplane began to ascend, pilot Henry Arnold nosed it into the wind and caught a wing tip on the surface, causing the aircraft to crash.

Arnold suffered a minor laceration to his chin while the other flyer, Roy C. Kirtland, was uninjured. The Model H, though, bore the brunt of the impact with a broken propeller, pontoon and other damage. The plane was eventually repaired.

Though not a major accident, this incident was one of several in a series of events that would cause the pilot to develop a near-career-ending phobia: a fear of flying. In the early days of aviation, when technology was still primitive and pilots were learning on the fly, Henry “Hap” Arnold—the man who would become an aviation pioneer, one of the first military pilots, lead the Army Air Force to victory in World War II and later establish the U.S. Air Force as the best in the world—could not bring himself to get back into the cockpit of an airplane.

“I cannot even look at a machine in the air without feeling that some accident is going to happen to it,” he told his commanding officer at the time.

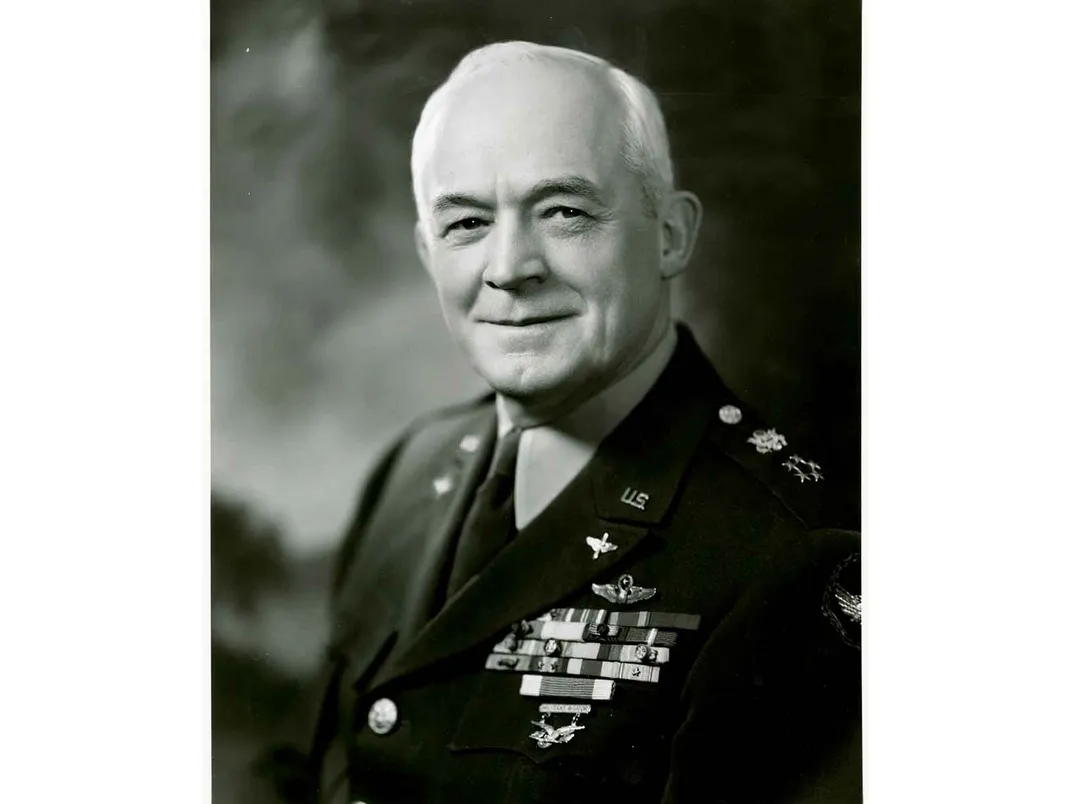

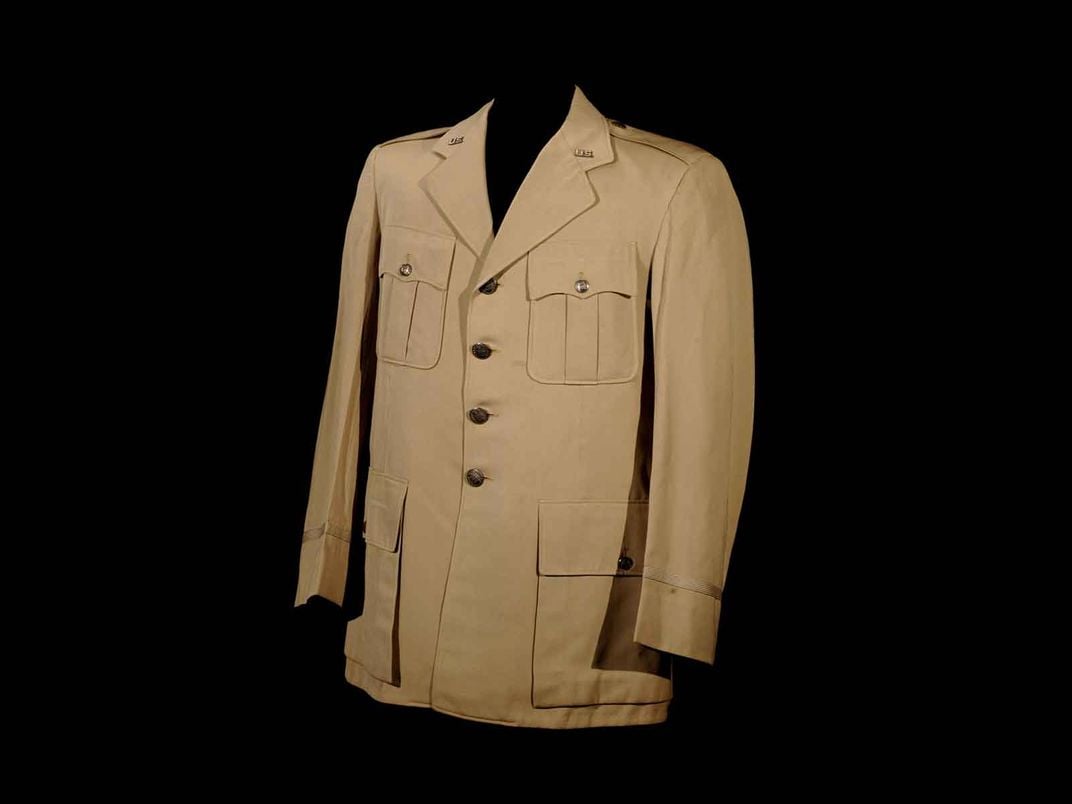

Of course, Arnold did overcome his fear of flying. Otherwise, there would be no display dedicated to the author of American air power at the Smithsonian’s Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia, an extension of the National Air and Space Museum. Included are Arnold’s uniforms, insignia, military coats and a desk he used at West Point Military Academy and during his service in the Army Air Force, as well as other items. A portrait photograph by the renowned Yousuf Karsh, depicting the five-star general in full military regalia, is held in the collections of the National Portrait Gallery.

“Another really cool thing we have is a pre-World War I flying helmet Arnold wore,” says Alex Spencer, curator in the Aeronautics Department at the Air and Space Museum. “We have quite an interesting package of artifacts, including his World War II uniform, though it is missing his five-star insignia and Military Aviation Badge. Arnold designed that badge with Thomas Milling, a good friend and also an aviation pioneer. Only 13 were issued. Arnold was buried with his badge.”

Arnold soared into history at the very beginning of military aviation. In 1911, he transferred from the Cavalry to the Signal Corps, which at the time had control of planes for the Army. One of his first duties was to be taught the intricacies of motorized flight from the two men who started it all.

“Arnold went out to Dayton, Ohio, and learned to fly from the Wright brothers,” Spencer says. “He was a military aviation pioneer and had pilot certificate number two.”

Arnold won the very first MacKay Trophy, which recognizes the most meritorious military flight of the year. He became one of the Army’s first aviation instructors and was the first American pilot to carry mail. Arnold was also the first to fly over the U.S. Capitol and carry a Congressman as a passenger. In addition, he moonlighted as a pilot in two silent movies, The Military Air-Scout and The Elopement.

The young officer, who was nicknamed “Hap” because of his near-constant grin, did not see combat in World War I. Instead, he managed aircraft production and procurement for the Army and supervised construction of airfields while recruiting and training large numbers of airmen. This experience would prove invaluable 20 years later.

After the war, Arnold became an acolyte of Col. Billy Mitchell, a controversial advocate of air power who wanted the Army Air Service, now separated from the Signal Corps, to become an independent branch of the military. That association did not sit well with Army brass.

“Arnold was not always the most popular of individuals,” Spencer says. “He was a disciple of Billy Mitchell and proponent of strategic bombing, which was not accepted military doctrine in the 1920s and ‘30s. He also testified on Mitchell’s behalf during his court-martial, and that put Arnold in hot water. He was persona non grata for quite some time.”

Arnold outlasted that ostracization to become chief of the Army Air Corps, successor of the Air Service, in 1938. With the realization that another war was imminent, he oversaw the buildup of his small command into a dominant presence. With only 800 planes at the start of hostilities, the American air force became the world’s largest with 300,000 aircraft at the end of the war. His organizational skills and grasp of strategic air power were the impetus he needed to succeed.

There was no limit to Arnold’s determination to maintain an effective supply line of planes for the war effort. He closely scrutinized all aspects of production to make sure aircraft were up to specifications for his strategic bombing campaigns of Germany and Japan. When the B-29 Superfortress encountered developmental problems, the general immediately flew to Kansas to personally inspect the assembly line.

“Arnold’s capabilities were phenomenal,” Spencer says. “There is no questioning his ability to keep things organized. One thing that was impressive was that if something wasn’t working, he fired people left, right and center. He didn’t care if you were his friend or not. If you heard Arnold was on the way to visit you, you had the fear of God in you.”

Racism was an institutional problem for the U.S. military in the years leading up to and including World War II. As in many parts of the country, segregation was a prominent feature of the armed forces as African Americans were not allowed to serve with white men and women.

Unsurprisingly, Arnold was a product of his time. Like most officers of the day, he was against an integrated military, and in fact at first opposed the creation in 1941 of the Tuskegee Airmen, the all-Black air wing. Arnold even tried to scuttle the program because he saw “Negro officers serving over white enlisted men creating an impossible social situation.”

However, he relented and later ordered his commanders to “take affirmative action to insure that equity in training and assignment opportunity is provided all personnel.” In 1948, the newly minted Air Force—under Arnold’s leadership—was the first service branch to fully integrate following President Harry S. Truman’s executive order ending segregation in the military.

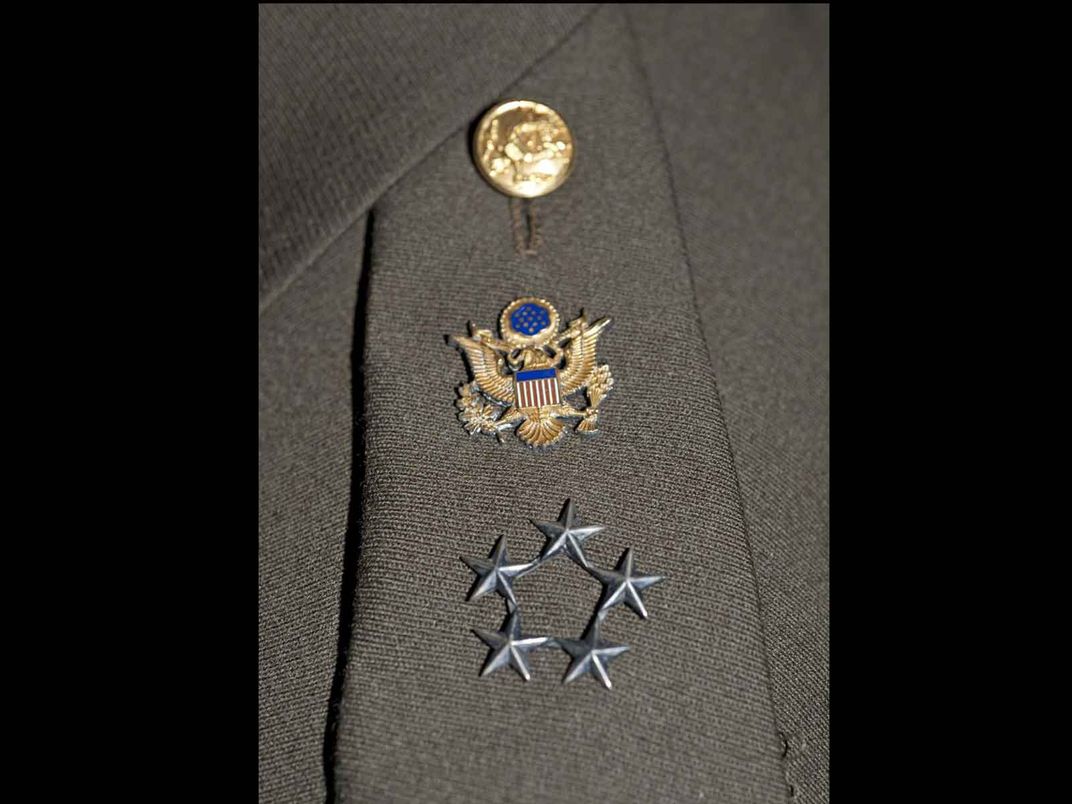

The Mitchell acolyte was rewarded in March 1942 when the Army Air Force was allowed to function as an independent command, although nominally still under Army control. For his efforts, Arnold was promoted to a full general with four stars in 1943 and then General of the Army with five stars in 1944.

In 1947, when the U.S. Air Force became a completely separate branch, Arnold was made General of the Air Force. He is the only person in history to serve as a five-star general in two different military branches. Arnold, who suffered four heart attacks in World War II, died of cardiac problems in 1950.

All of which makes the fact that Arnold had a fear of flying even more remarkable. In 1912, he survived at least two crashes and managed to pull out of an uncontrolled spin at the last moment in a near-fatal incident. Arnold was also distraught over the deaths of two close friends and fellow pilots that year, Lt. Lewis Rockwell and Al Welsh, a Wright brothers flight instructor.

“It changed his career trajectory for a while,” Spencer says. “Because of Arnold’s knowledge, his superiors dragged him back into flying—really against his will. There were so few people who had any real knowledge of aviation at the time, so he was needed.”

Arnold faced his phobia by taking a series of short flights until he gradually become comfortable in the cockpit again. If he hadn’t, it is inconceivable to think about what might have been.

“To consider that he had this fear of flying and ended up where he did is rather remarkable,” Spencer says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/dave.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/dave.png)