How Girls Have Brought Political Change to America

The history of activism in young girls, who give voice to important issues in extraordinary ways, is the topic of a new Smithsonian exhibition.

:focal(1671x542:1672x543)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b2/7f/b27f3c3d-90e2-44a3-9316-30e512689f7d/gettyimages-937394578.jpg)

Tensions were running high in the Wadler household as its members prepared for 11-year-old Naomi Wadler’s big day. The following morning, she was to speak at the 2018 March for Our Lives rally in Washington D.C. An argument had broken out between Naomi, who wanted to wear a casual outfit of all black to the rally, and her mom, who wanted her to wear a dress, or at least something more colorful. Naomi’s aunt proposed a solution: she would knit Naomi a bright orange scarf—orange for gun violence awareness—to wear with her outfit as a colorful compromise.

Leslie Wadler stayed up that night knitting the scarf and watched two movies in the process. By 4 a.m., the “two-movie scarf” was ready. The scarf has since become an icon for Naomi and her message about the disproportionate impact gun violence has had on black girls and women.

“It was really a spontaneous, last-minute addition to my outfit, so I’m glad it stuck with people,” Wadler says. “I really wanted the day to go as smooth as possible, because I thought that there were only going to be like 200 people there; I wasn’t expecting almost a million people at the march. I didn’t really think it was that big of a deal, and I figured it would make my mom happy, it would make my aunt happy, so why not just wear it.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8d/fe/8dfe2c71-d984-4aff-92c8-7e5776a08eb2/naomi-wadler-scarf.jpg)

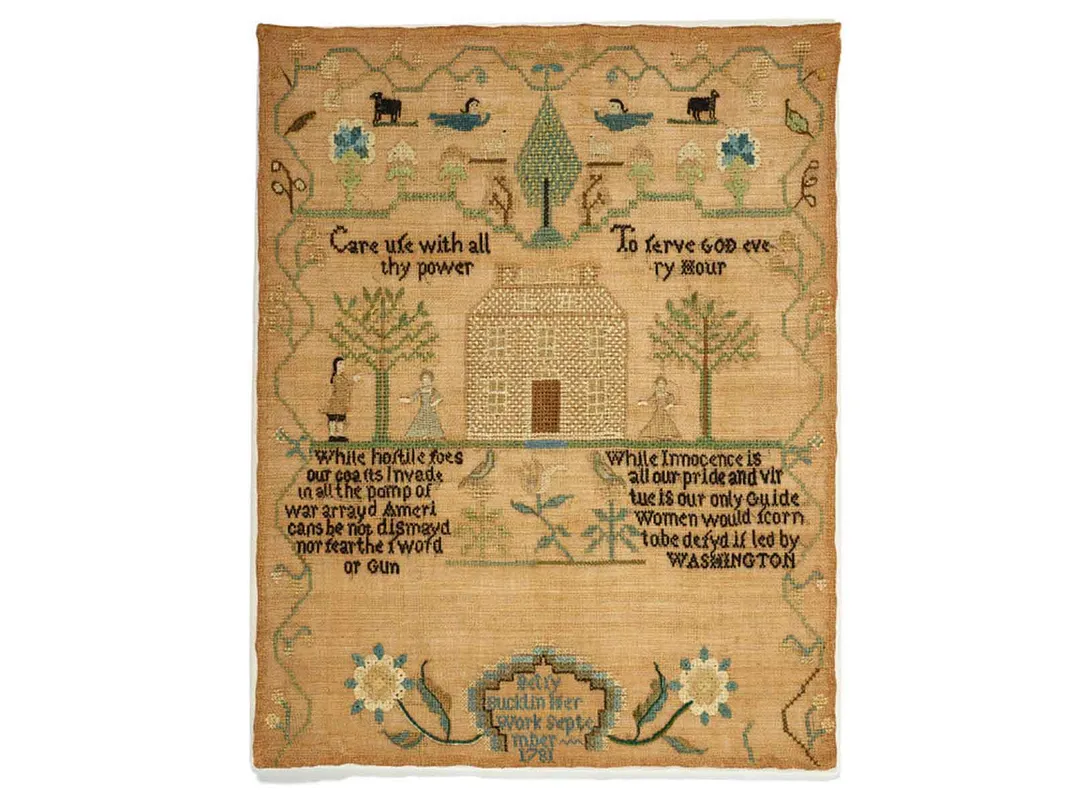

Since her speech, Naomi has become a face of American activism. The now-iconic scarf she wore is prominently displayed at the new exhibition “Girlhood (It’s Complicated),” which recently opened at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. The exhibition, which will tour the country from 2023 to 2025, commemorates the political impact girls have had in the political landscape, as a part of the American Women’s History Initiative’s celebration of the centennial of women’s suffrage in the United States. Naomi’s scarf is among hundreds of featured objects dating from 1781 to 2018.

“We didn’t want to replay the story that most people know, or even some of the surprising parts about suffrage because we knew other places were doing that, and doing that really well,” says Kathleen Franz, lead curator of the exhibition. “We wanted to make it a living question. So instead of saying ‘What’s the history of suffrage?’ we ask, ‘What is it like to grow up female in the U.S., and how does being female give you a political consciousness?’”

A personal connection to the tragic shooting in February 2018 at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in which 17 students and staff members were gunned down in their classrooms in Parkland, Florida, is what prompted Naomi’s activism. Her mother’s best friend is Jennifer Guttenberg, and her daughter, Jaime, was killed in the shooting. When Naomi heard about it, she was moved to action.

“I had always tried to have political conversations with my mom,” Naomi recalls, “But it never occurred to me that kids could actually act on the things that they said. So the month after the Parkland shooting, seeing all of these kids who were older and younger than me speaking out and having people listen to them was truly inspiring to me, and it made me want to do something.”

She and a friend of hers decided to organize a walkout with their fifth-grade math class at George Mason Elementary School in Alexandria, Virginia. They wrote letters to their principal explaining why, and held group meetings at classmates’ houses in preparation. On March 14, 2018, with the help of parents and students, Naomi and 200 of her classmates left their classrooms, and for 17 minutes plus one minute they held a vigil in remembrance of the victims of the Parkland shooting, as well as for Courtlin Arrington, a Birmingham, Alabama black girl who was shot and killed by her boyfriend in school, but whose death received little media attention.

Eight days later, Naomi’s family received a call asking if Naomi would be willing to speak at the Washington, D.C. rally, which was to take place two days later. They agreed, and so with little time, Naomi took the day off from school to write her speech, finishing only just about an hour before she went to bed. The speech was her first, and she felt terrified standing before the shockingly large crowd, but Naomi remembers the speech as one of her best even among the many she has delivered since then.

Now, as a full-blown student-activist, she balances school with her work in bringing awareness to how black girls and women are disproportionately affected by gun violence. Naomi says that she feels pressure to grow up more quickly because of her place in the public eye, but that hobbies like tennis and watching shows like “Grey’s Anatomy” and “The Vampire Diaries,” as well as doing school work, help her to unwind from being a public figure.

Now at the age of 13, Naomi already has many accomplishments under her belt. She has spoken at numerous events including the Women in the World annual summit and the Tribeca Film Festival. She has also appeared on “The Ellen DeGeneres Show,” one of her most memorable experiences, and she works on a web show with NowThis called “NowThis Kids,” which seeks to explore societal issues in a way that is accessible to those under 18.

“I think that a lot of people underestimate girls and their power and their ability to make change happen,” Naomi says. “I and so many others are another representation in numbers of how big of a difference girls, and girls of color, can make in society no matter what holds them back. . . I’m so proud of the other girls who are featured in the exhibit, and of myself, and I hope that when people read or hear of my story, they use it to inspire themselves and the people around them.”

View the Virtual Opening of the New Exhibition "Girlhood (It's Complicated)"

For Isabella Aiukli Cornell, political awareness began at a young age as well. In third grade, Cornell, a member of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, began making presentations about indigenous people and their history in response to Oklahoma Land Run reenactments that had students act as settlers staking claim to the land. Many indigenous people viewed the reenactments, which have since been banned in Cornell’s own Oklahoma City school district, as a racist celebration of the theft of their land.

The need for a more indigenous-sensitive curriculum continued in middle school. Within the first few days of eighth grade, Cornell’s history teacher used the words “violent, vicious vermin” as well as “cannibals,” to describe some of the indigenous people he was teaching about, prompting Cornell and her mother to present on history from the indigenous perspective in the same class a few days later.

“There were a lot of different instances where my identity as indigenous almost made me feel ashamed,” Cornell says. “But as time grew on, I began to advocate really strongly against some of the things that I went through so that other indigenous youth wouldn’t have to. That’s when I started to really embrace my indigenous identity. I’ve always loved my culture and my heritage, and at times I was bullied for it, but I never really forgot who I was, and where I came from. And for that reason, I’m really proud of who I am today.”

When Cornell’s senior prom rolled around in 2018, she knew she wanted to have her identity and culture represented in her dress. She decided to commission Della Bighair-Stump, an indigenous designer she had long admired, to create a beautiful tulle dress. To bring attention to the many indigenous women who have disappeared or have been murdered but never accounted for, Cornell also decided she wanted the dress to be red—the color made symbolic by the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women movement.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cb/88/cb88009f-0890-4a96-bdc0-6caafc43e593/isabella-aiukli-cornell-choctaw-prom-dress.jpg)

The dress also features a diamond-shaped beaded applique, symbolizing the diamondback rattlesnake, an important part of Cornell’s Choctaw heritage. Choctaw farmers traditionally venerated the diamondback rattlesnake as a protector of crops.

Cornell’s dress ended up trending on social media—a result that brought the desired attention to the movement.

“[Being an indigenous woman] is such a central part of my identity because we exist because of a thousand years of prayers and dreams and hopes of our ancestors who came before us, who got us to be where we are today,” Cornell says. “And so that’s always really important for me to remember.”

Another emblematic dress in the show belonged to Minnijean Brown-Trickey. Her 1959 graduation dress symbolizes the significance of education in a girl’s life—one of the exhibition’s primary subjects along with news and politics, wellness, work and fashion.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ab/db/abdb8d1e-157b-41e0-bc7a-c4a3ea9c50a9/minnijean-brown-graduation-dress.jpg)

To Brown-Trickey, the dress represents a victory over the intense discrimination and terror she faced at Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1957. She was one of the nine black students who had to be escorted by the National Guard to school after the recently desegregated school denied them entry. The school later maliciously expelled Brown-Trickey for verbally retaliating against a bully who had hit her. She left the south, and she moved to New York to complete her education at the New Lincoln School in Manhattan.

“Growing up in the Jim Crow South, you don't get to feel really normal because all the images are of white girls in crinolines and sitting at soda fountains and doing things that I couldn't do,” Brown-Trickey recalls. “So to me, [graduating at New Lincoln] was the realization of a fantasy. I had to be a normal girl in America. So there I was. Being a normal girl. I wasn't being brutalized. In my school, I wasn't being segregated. Oh my God, it was just so amazing.”

At 79, Brown-Trickey remains an activist, and she stresses the importance of listening to what young people have to say. She says she tries to honor young people, listening to them the way she would have wanted to be heard.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e6/ed/e6ed437a-22d6-4fca-91d2-69ae1816549e/gettyimages-1040227748.jpg)

Having spoken with Naomi Wadler recently, Brown-Trickey says, “She has everything; she is the most American girl you can imagine. . . but even she feels devalued in American society. I said to her, ‘You remind me of my girlhood. You have all this value, and somehow it isn’t recognized.’ And I don’t think it’s just black girls, it’s all girls. . . She is every girl, and I was every girl.”

Franz says that throughout American history, girls, though not enfranchised, have often taken different forms of action to make their voices heard.

“We really wanted to convey this idea that politics is personal, and it’s a lot of different things from being on social media, to joining a march, to doing a sampler endorsing George Washington, to refusing to wear something that something somebody tells you to wear, or to desegregate a school,” says Franz. “There’s this whole range of things that are political acts. And we really wanted to show that girls, a group of people by age, who have been often overlooked by museums because we don’t see them as having a public life, they really were historical actors who made change. They had political voices and we are trying to recognize that through this exhibition.”

“Girlhood (It’s Complicated)” is currently on view at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. To protect visitors during the pandemic crisis, visitors must sign up for free timed-entry passes.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tara.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tara.png)