How This Globetrotting Artist Redefines Home and Hearth

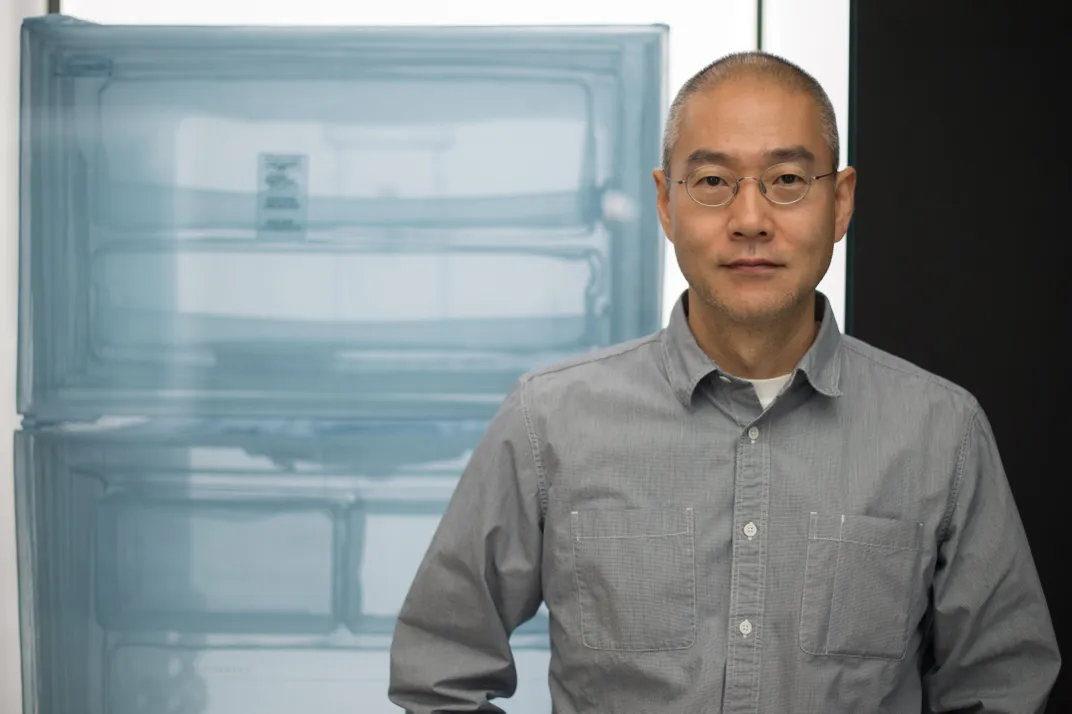

An ethereal 3D installation by the Korean-born Do Ho Suh combines places the artist has lived in the past

You are invited into Do Ho Suh’s apartment. You put down your bag, remove your coat and step inside. The hallway changes color as you proceed, first pink, then green and then blue. It’s narrow, but it feels spacious. There is a red staircase outside, and beyond it people are moving around. You can see them, right through the walls. Cabinet handles appear rigid, but the doors they sag slightly. A doorknob pulses almost imperceptibly in the breeze. Back at your house, the only things that behave this way are cobwebs, but here, everything—door panels, chain locks, light switches, sprinkler system—dissolves delightfully into colored light.

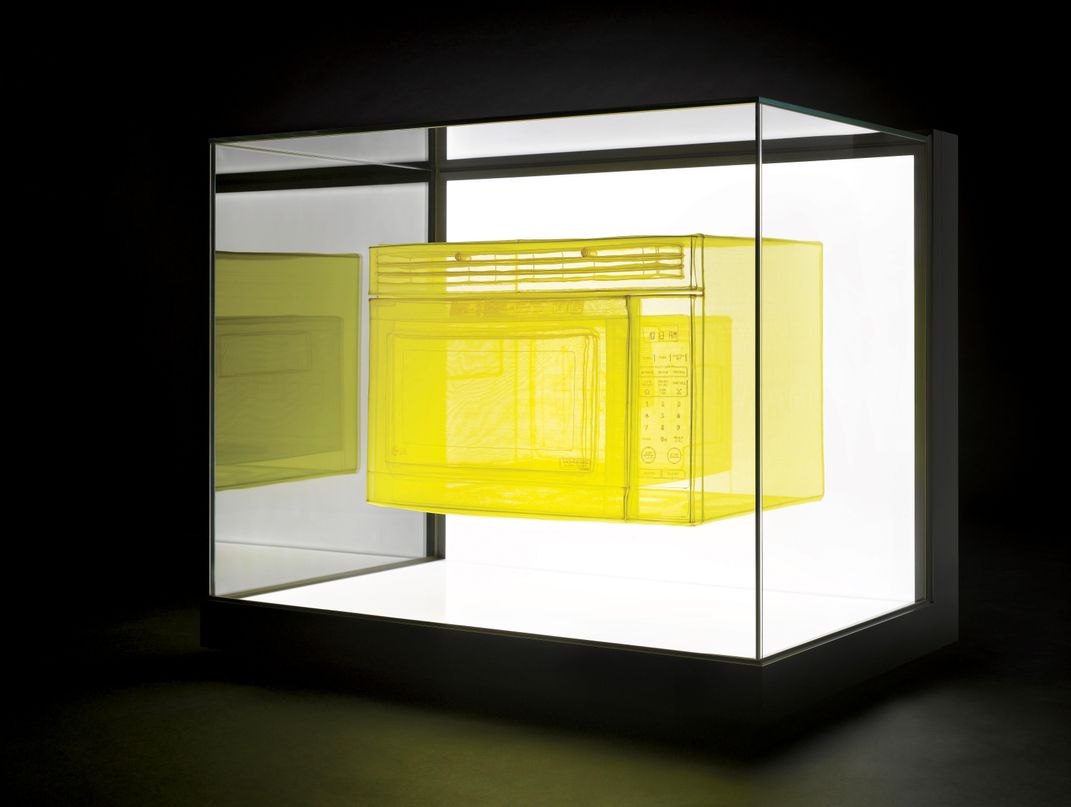

“Almost Home,” Suh’s solo exhibition on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, is filled with fabric sculptures big and small, all of them monochromatic actual-size 3D recreations of the walls and moldings and fixtures of rooms where he has lived in New York, Berlin and Seoul. The gallery space is lined with vitrines that hold everything from an old-fashioned radiator, pink and prim, its floral decoration picked out in subtle embroidery, to neatly rendered electrical outlets and circuit breakers in red and blue, to a microwave oven, a radiant block of yellow. Down the center of the gallery runs the procession of hallways, ethereal representations of those where Suh has walked.

Many top-tier contemporary artists are international nomads, and Suh is no exception. He currently is based primarily in London, but he keeps a small live and work space in New York and travels to Korea several times a year. He doesn’t know where he’ll be after London. When you live in several countries, the idea of home exerts a powerful attraction.

His precise, poetic documentation of the spaces he has lived began when he was a graduate student in New York City. His first attempts to reproduce his studio were in muslin, but the cloth was unable to convey both the weight of architecture and the weightlessness of memory. “I needed something to render this nothingness,” he says, “so that’s where this translucent, thin, very lightweight fabric came in.”

Suh, who was born in Seoul in 1962, knew that to realize his vision, he’d have to look toward his boyhood home. His mother helped him source the fabric and to find people who could teach him to sew it. “My mother has extensive knowledge in Korean culture and heritage, and she knew a lot of artisans, basically old ladies, who had the techniques to make traditional Korean clothing,” Suh says. “Those ladies were [what] in Korea we call a National Human Treasure, because they are the ones who learned very traditional techniques, and those techniques are basically disappearing.”

The women had been recognized by the government as part of an effort to preserve aspects of the country’s culture that were uniquely Korean. It’s a project that arose partly in response to the damage done by the Japanese colonial occupation of the country, a 35-year period that ended in 1945, with the Axis defeat in World War II.

“The Japanese systematically tried to erase Korean culture,” Suh explains. “Koreans were not allowed to speak Korean. They learned Japanese and they had to change their names to Japanese names.”

The upheaval didn’t end with the war. South Korea was becoming a modern industrialized nation, increasingly Westernized, and urban renewal often continued what the Japanese had started. Historic buildings were torn down. “When you go to Seoul, the palace complex that you see is much smaller than it used to be,” says Suh. As the complex shrank, Suh’s father, the painter Seok Suh, was among the people who collected timbers from the dismantled buildings.

Among the palace buildings that escaped the wrecking ball was an idealized version of a typical scholar’s house, built by the king in the 19th century to reflect the high esteem in which Korea holds its scholars. When Seok Suh decided to build his family a home in the early 1970s, it was this structure he chose to emulate, and he constructed it using the timbers he had reclaimed from other parts of the palace complex. This was the house Do Ho Suh grew up in, and when he goes home to Seoul, it is still where he stays. Because traditional-style buildings are increasingly rare in today’s Korea, the Suh family’s house has come to represent authentic Korean architecture, even though, as Suh ironically observes, “it was a copy of a copy.”

And Suh’s fabric sculpture of it was yet another copy. “My attempt was to move my childhood home to the U.S., where I was living,” Suh says.

During his student years, Suh moved about nine times. This continually uprooted life imposed conditions on him that would prove fruitful for his work. “Making my life light was a very important issue, almost like it’s a condition for my survival,” he says. “Everything had to be collapsible, flat-packed. My work was not the exception.” He carried his early works around in suitcases. Today they are crated for shipment, but they still fold flat.

Nostalgia, in the sense of craving a past that never existed, is generally frowned on in contemporary art circles, but Suh embraces the word, saying that his work is “all about dealing with the sense of loss.” His nostalgia, however, is directed toward events that actually happened, places that actually exist. It is an honest emotional response to a life shaped by cultural and personal dislocations, by the unalterable passage of time, and he sees no reason to look away from that.

Suh’s most skillful trick is to create the proper balance of presence and absence, to keep the audience in the moment through artworks that are largely about what is not there. He acknowledges the contradiction at the heart of his pursuit of the “intangible object.”

“I want to hold onto it,” he says, “but at the same time I want to kind of let it go.”

The holding on requires careful measurement of the structures he inhabits. Suh doesn’t start right away. Only after a room acquires the invisible veneer of memory does the measuring tape come out, sometimes only when he’s ready to move out. It’s a painstaking process, requiring Suh to convert English units to metric in his head, much as he mentally translates English back and forth to Korean as he speaks.

Though cultural dislocation is embedded even in the act of measuring, the process is reassuringly physical. “By measuring it, you are able to have physical contact with the walls and surfaces in the space. You basically have to touch everything in the space,” Suh says. “The measurement somehow quantifies the space. The space is not an ambiguous thing. It becomes real.”

As he works, Suh finds the pasts of his dwellings written in their imperfections. “The houses and the apartments that I have lived in were all very cheap—tenant apartments, especially when I was a student,” he says. “It was all renovated over the years without any specific logic. You found very odd decisions here and there—floors not completely leveled or walls that are not plumb. You discover the characters of the buildings and then you start to think about the story behind the walls, and memories and histories. You become an archaeologist, almost.”

And then he takes that history on the road, where it interacts with exhibition spaces, which like cheap student apartments, host the work of many different artists over the years, telling many different stories that echo in the memories of those who regularly visit them. “His works are obviously not site-specific in a traditional sense, in that they are not made for the sites in which they are installed, but their meaning changes with each location and context,” says curator Sarah Newman. “Do Ho’s personal spaces accrue the context of the public places in which they are sited. In our galleries, the corridor from New York to Berlin to Seoul is intertwined with the history of the Patent Office, [the building that now houses the museum was originally designed for this 19th century federal agency], and the building’s history as a Civil War hospital.”

The highly photogenic artwork belies the conceptual heft of Suh’s works. As always, the risk of making something so Instagram-friendly is that museumgoers may be too busy taking photographs to enjoy the exhibition. But that’s not proving true in this case. “When people come into the show, they are smiling, looking up and around,” says Newman. “I've been thinking about it as similar to the experience of the cherry blossoms, which affects the air and the quality of the light.”

Also, it is only through physical movement that the spaces within the works are activated, drawn back out of memory. Through movement, you perceive the way Suh reveals not just the light and space in a sunlit room but the compressed volume hidden inside a fire extinguisher, the amount of air trapped behind the seal of a microwave oven. “Even though those are all static sculpture pieces, the important thing is, it’s about the movement,” Suh says. “Because as a beholder of the work, you need to move your body to experience the work. And that’s the way I experience my life.”

“Do Ho Suh: Almost Home” is on view through August 5, 2018 at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Glenn_Dixon2.JPG)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Glenn_Dixon2.JPG)