How Jazz, Flappers, European Émigrés, Booze and Cigarettes Transformed Design

A new Cooper-Hewitt exhibition explores the Jazz Age as a catalyst in popular style

“The Jazz Age” brings to mind flappers, Gatsby, epic parties, and, of course jazz. But if high energy defined the era, so did its tension—the wild nightlife scene met with Prohibition; a rapid rise in American innovation conflicted with a longing for European tradition; great prosperity gave way to the Great Depression. The friction of all these contradictions shaped the century that followed—in popular design perhaps more than in any other area of American life.

These contrasting influences and the important role they played in the 1920s are the subject of an expansive new show, “The Jazz Age: American Style in the 1920s,” the first major museum exhibition to look squarely at American style during this creatively combustible era.

The show, which runs through August 20 at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York City and is co-organized with the Cleveland Museum of Art, spotlights this significant era when American taste and lifestyle underwent a transformation. Reflected in the furnishings, jewelry and design of the period, this was an era where boundaries were being tested, and in some cases breached.

“It’s the source of so much that happens in the 30s and beyond,” says Sarah Coffin, a Cooper Hewitt curator and head of product design and decorative arts.

The more than 400 works of jewelry, fashion, architecture, furniture, textiles and more paint a picture of a wildly energetic era of design, emboldened by vivid color and innovation. To navigate such a huge subject, the show is organized over two floors into broad themes that help illustrate the major design trends and tensions shaping the era.

“You first gather the universe of objects, which is many more than you can show,” says Stephen Harrison, curator of decorative art and design from the Cleveland Museum of Art, describing the winnowing process that the show’s organizers first faced. “Then you begin to ask yourself: What questions do they pose? What adjacencies? What relationships develop? And as we began to refine our ideas we refined our objects.”

The first theme that visitors encounter is perhaps the one they might least expect: “Persistence of Traditional Good Taste.”

The Jazz Age was not all about the new and different: This was a time when Americans embraced French and English designs of the 17th and 18th centuries, seeking out handcrafted antiques to elevate their social status.

“There were a lot of people in this country who continued to collect antiques, buy reproductions, and do things in traditional taste, throughout the decade,” says Coffin.

Even as the world was rapidly changing, original works in American colonial designs as well as those from 17th- and 18th-century France and England still conveyed social status. The masterful traditional ironwork of a Samuel Yellin fire screen, a blanket chest with elements of Persian manuscript painted by Max Kuehne, and a secretary made for a reproduction of John Hancock’s house based on a model in the Metropolitan Museum of Art are examples of period works that museums, collectors and wealthy households collected.

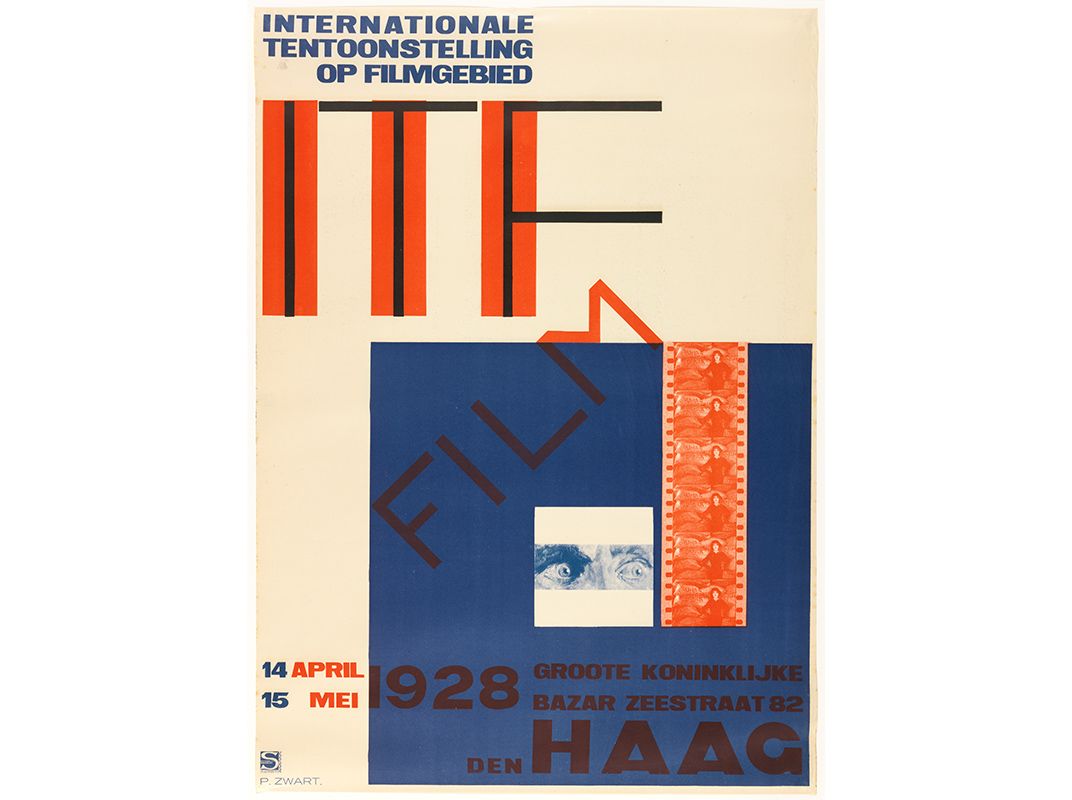

But novel European styles also were impacting American styles. Events such as the 1925 International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts held in Paris helped expose and educate Americans about the new designs making their debut across the Atlantic. Museums throughout the U.S. (Cooper Hewitt and the Cleveland Museum, as well as Chicago Art Institute, the Newark Museum, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Brooklyn Museum) displayed the works, acquiring many of the pieces, and making some available for purchase to the well heeled.

“These museums were all either establishing funds for the acquisition of modern European decorative arts during this period or hosting shows of modern European design that could then be retailed,” says Emily Orr, the Cooper Hewitt’s assistant curator of modern and contemporary American design.

For those with less disposable income, replicas soon became widespread and easily acquired—a subject tackled in the exhibition’s section “A Smaller World.” One of the great vehicles for this mixing of influences was the department store. Places like Lord & Taylor and Macy’s started their own workshops where craftsmen created pieces in the European style and made them affordable to the average consumer.

“It’s very hard for people to get their mind around today, but the president of the Metropolitan Museum wrote the introduction to a catalog of an exhibition that took place at Macy’s,” says Coffin. “The museum perceived that its job was to get the values of good design and so forth out to the American public and make the American consumer aware that they would support it—it couldn’t just be in a museum.”

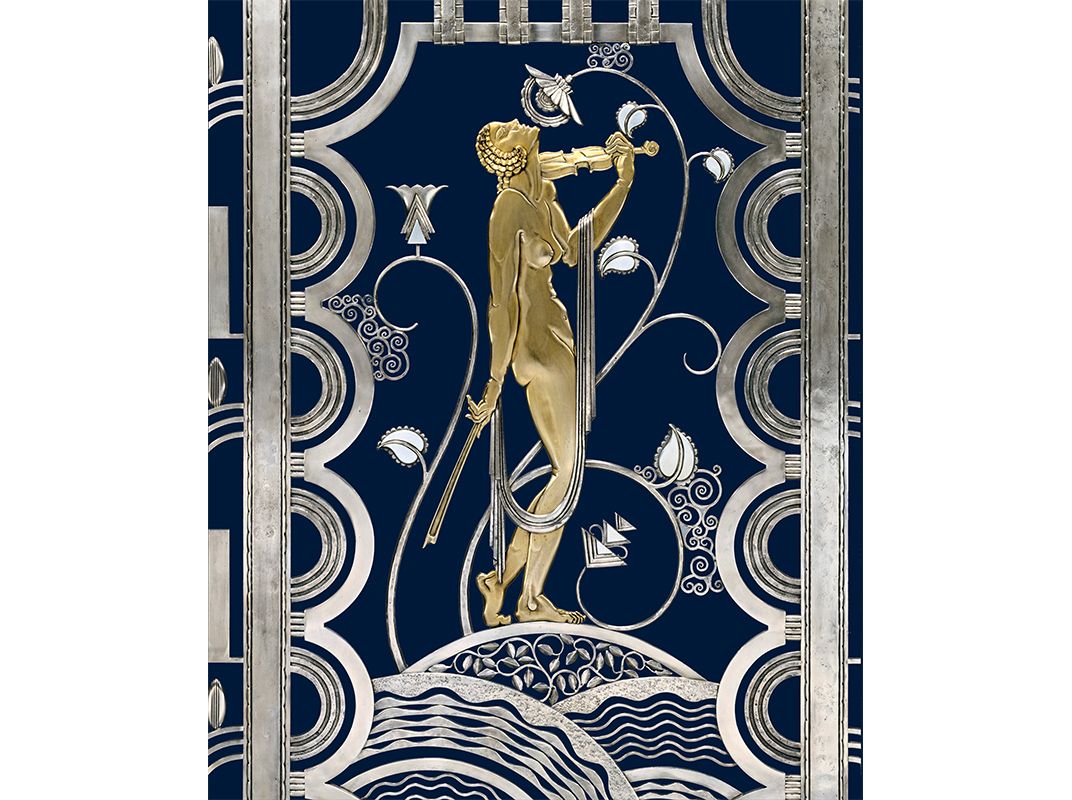

This created a peculiar interplay between the exclusive and the mainstream, as well as private and public. Coffin points to a striking pair of double doors by sculptor Séraphin Soundbinine and designer Jean Dunand that anchor the exhibition.

Solomon Guggenheim commissioned the doors—each featuring an angel atop a skyscraper blowing a horn. After he visited the 1925 Paris Fair and saw Dunand’s lacquer work, Guggenheim became convinced that the music room at his Port Washington home needed such a piece.

“You could in no way imagine that the people who had this sort of Baronial-style furniture in this house could possibly have the taste to do this,” says Coffin. “But apparently they decided they wanted to do this.”

After the doors were completed, the Guggenheim’s put them on public view at a gallery before even bringing them home. It was an early foray into art purchasing and curation that would soon grow (their first modern art acquisition would happen a year later).

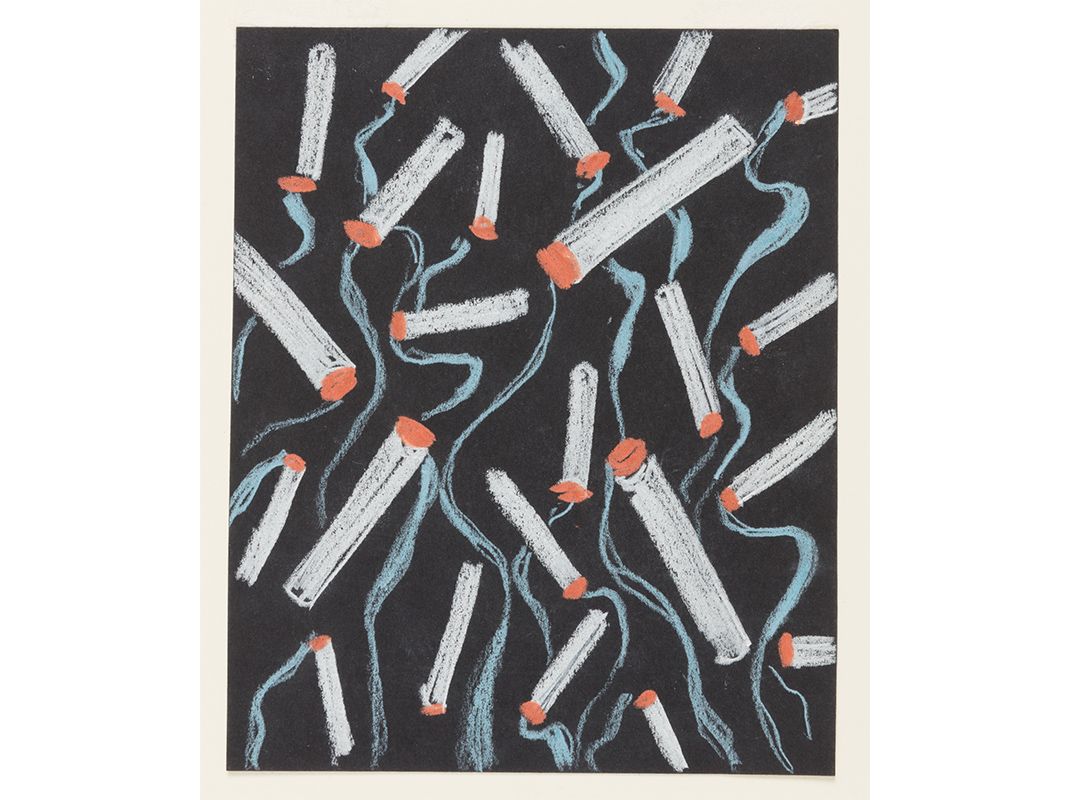

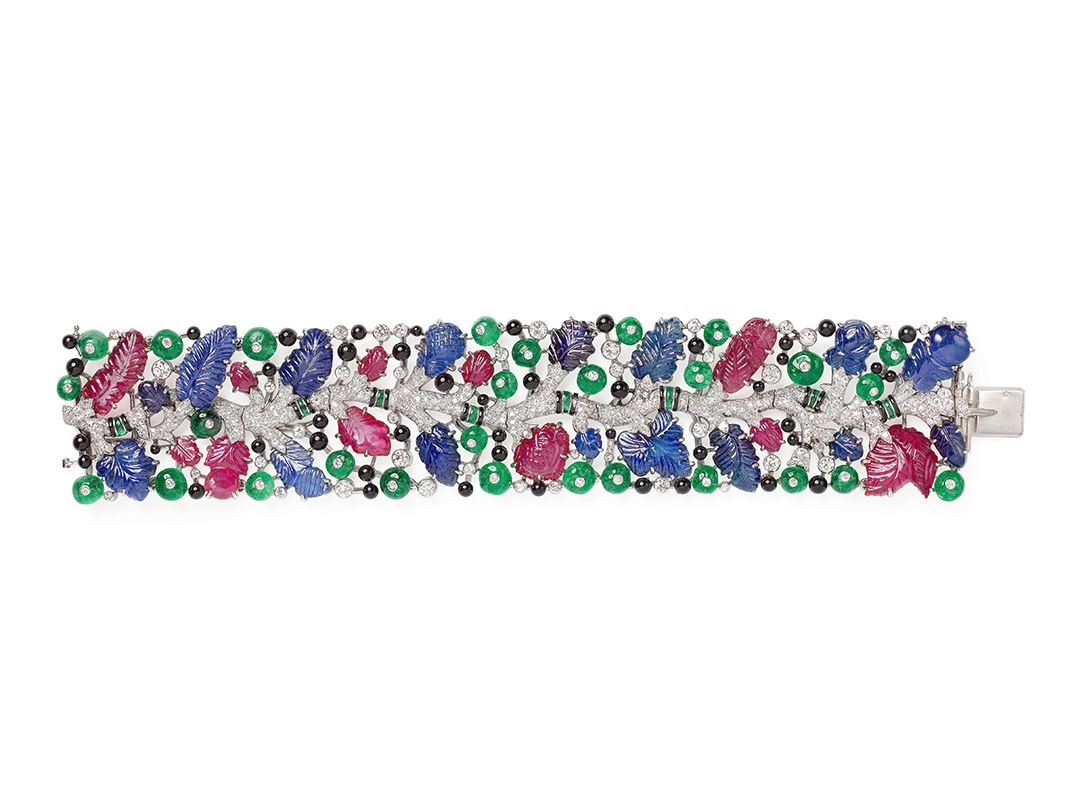

Of course, we can’t think of the 1920s without considering the raucous and boundary-pushing culture. The section “Bending the Rules—Stepping Out,” conveys that sense of possibility and changing norms and showcases how jazz music and the social world surrounding it shaped design. Vases with jazz dancers and a textile called Rhapsody, as well as film clips of Duke Ellington and other Cotton Club performers reverberate with the energy of the era. Jewelry that complements the new fashions—long necklaces the flappers would wear, a carved ruby necklace by Van Cleef & Arpels, a 1926 belt buckle featuring a scarab motif (King Tut’s tomb was excavated in 1922, so an Egyptian look took hold in jewelry fashion), and a pair of Cartier pieces owned by Linda Porter, wife of composer Cole, as well as other accessories for makeup and cigarette smoking, all reflect the era’s free-spirited liberation and changing social mores.

This carefree lifestyle was also something of a European import. A painting by New Orleans artist Archibald Motley “sums it up” as Coffin puts it—the artist spent a year in Paris on a Guggenheim scholarship, and the scene captures the energy of the era—a mixed-race club, people dancing, music playing, a woman smoking a cigarette and wine flowing freely.

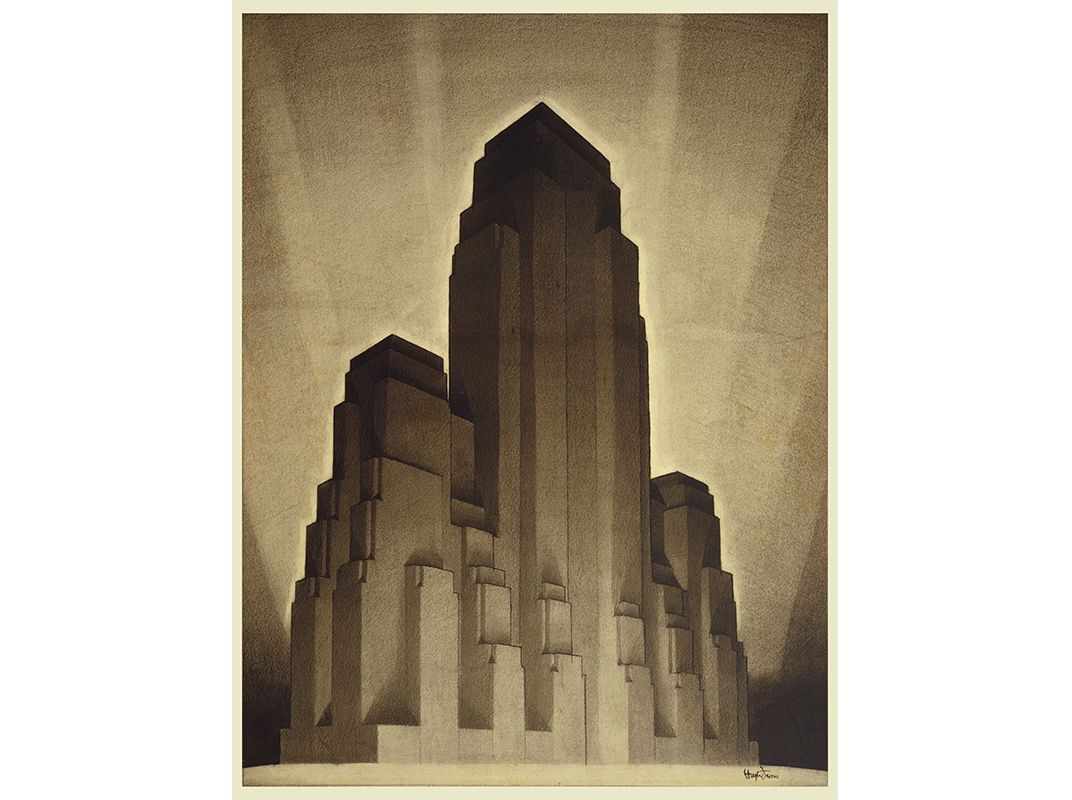

The European influence came not only from a greater ease and interest in travel, as more Americans visited and studied abroad, but also from the cascading effects of the First World War. Many designers had fled to the U.S. before and during the war, bringing their own influences and interests— émigrés like Paul T. Frankl, Joseph Urban, Walter von Nessen, and Richard Neutra brought with them experience in European abstraction as well as an admiration for American skyscrapers and cosmopolitan energy. This is perhaps best illustrated in the show by Frankl’s Skyscraper Bookcase Desk. The influence extended to the materials these Europeans used as well.

“Europeans were the first to bend chrome for their furniture, and it was this immediate sign of the new, but it also has to do with affordability and a desire for cleanliness in comparison to heavily detailed, ornate Victorian forms,” says Orr. “It was also used in cars and radios and symbolized the future.”

The cantilever chair is a major icon of this era. The adaptation of the form in a variety of materials shows how industrialization shaped the era. It was originally designed to be flat-packed and mass produced, but was remade into wood and leather and adopted by Walt Disney studios for its screening rooms.

“The industrial designer is a figure in this period brought on by so many manufacturers across media wanting to update their traditional lines for the modern consumer,” says Orr.

As Harrison puts it, “We wanted to define taste by looking at those modern-looking things versus those things that were modern in form and innovation and technology.”

“The Jazz Age: American Style in the 1920s,” is on view through August 20 at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York City.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alex_Palmer_lowres.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/90/1a/901a64a6-6b49-4e02-bc8d-dc3e44719964/3-wr.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alex_Palmer_lowres.jpg)