How Kara Walker Boldly Rewrote Civil War History

The artist gives 150-year-old illustrations a provocative update at the Smithsonian American Art Museum

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a9/e3/a9e3cbe3-019f-4c93-a855-3b56d6eddc52/confederate_prisoners.jpg)

There are certain truths about which reasonable people can agree. One of them is the fact that the Civil War was about the perpetuation of slavery—the theft of human lives, labor and dignity in pursuit of financial gain—and not about the tragic battle of brother against brother or some romanticized “Lost Cause.”

But disagreement inexplicably persists. One implication of it is that a century and a half after the end of the conflict, the shadows of this war hang over us like smoke from cannons that have never stopped firing.

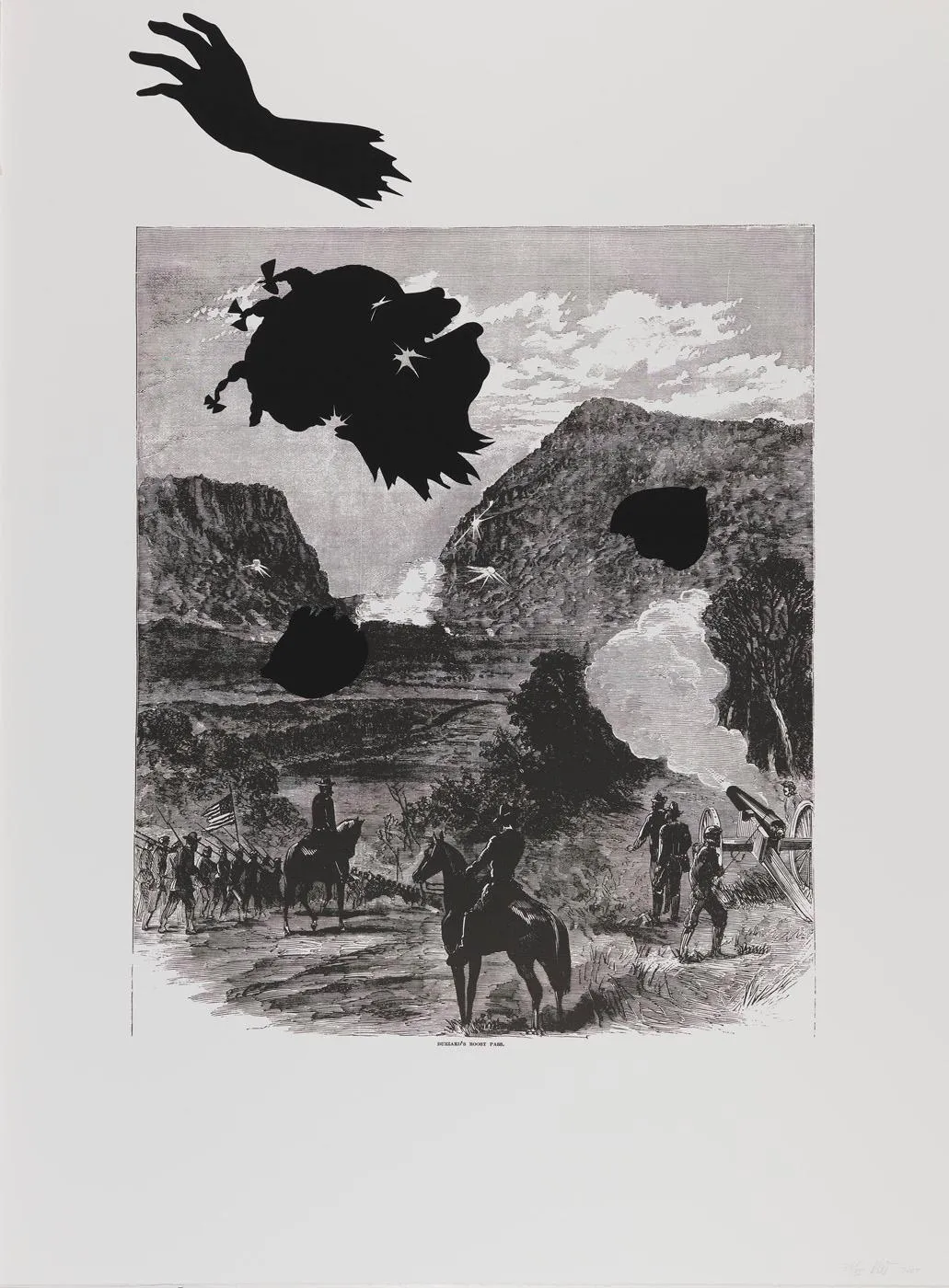

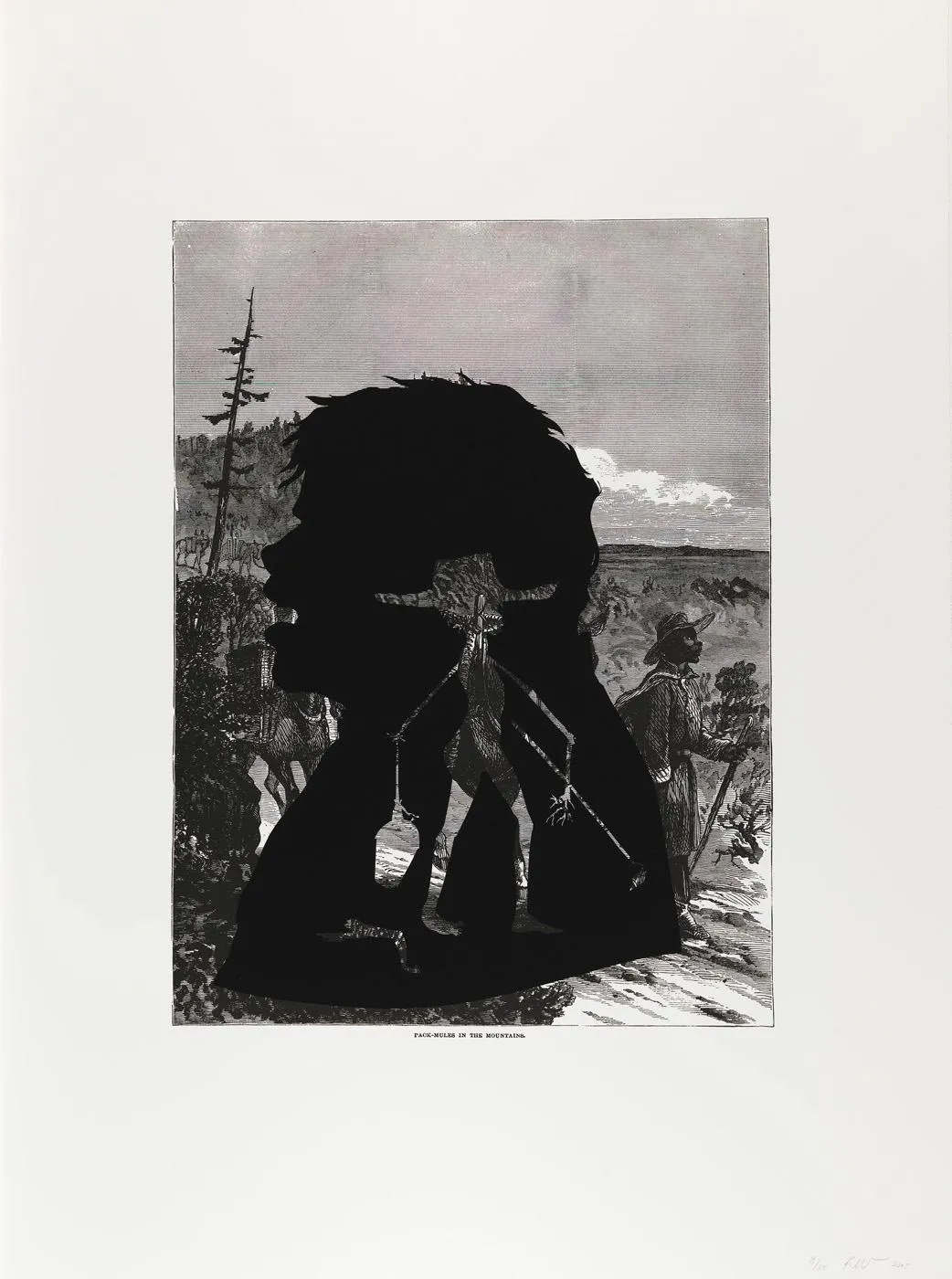

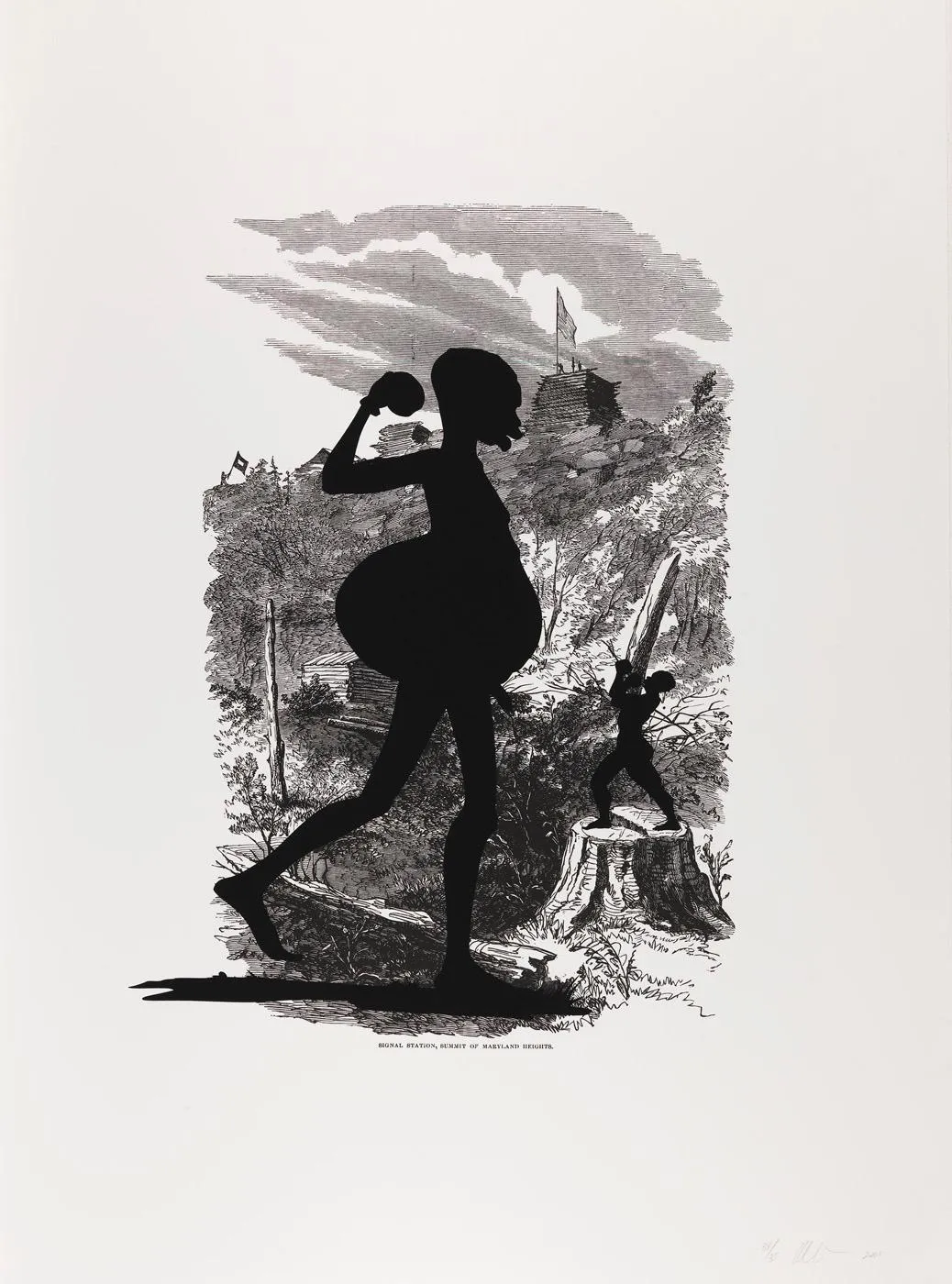

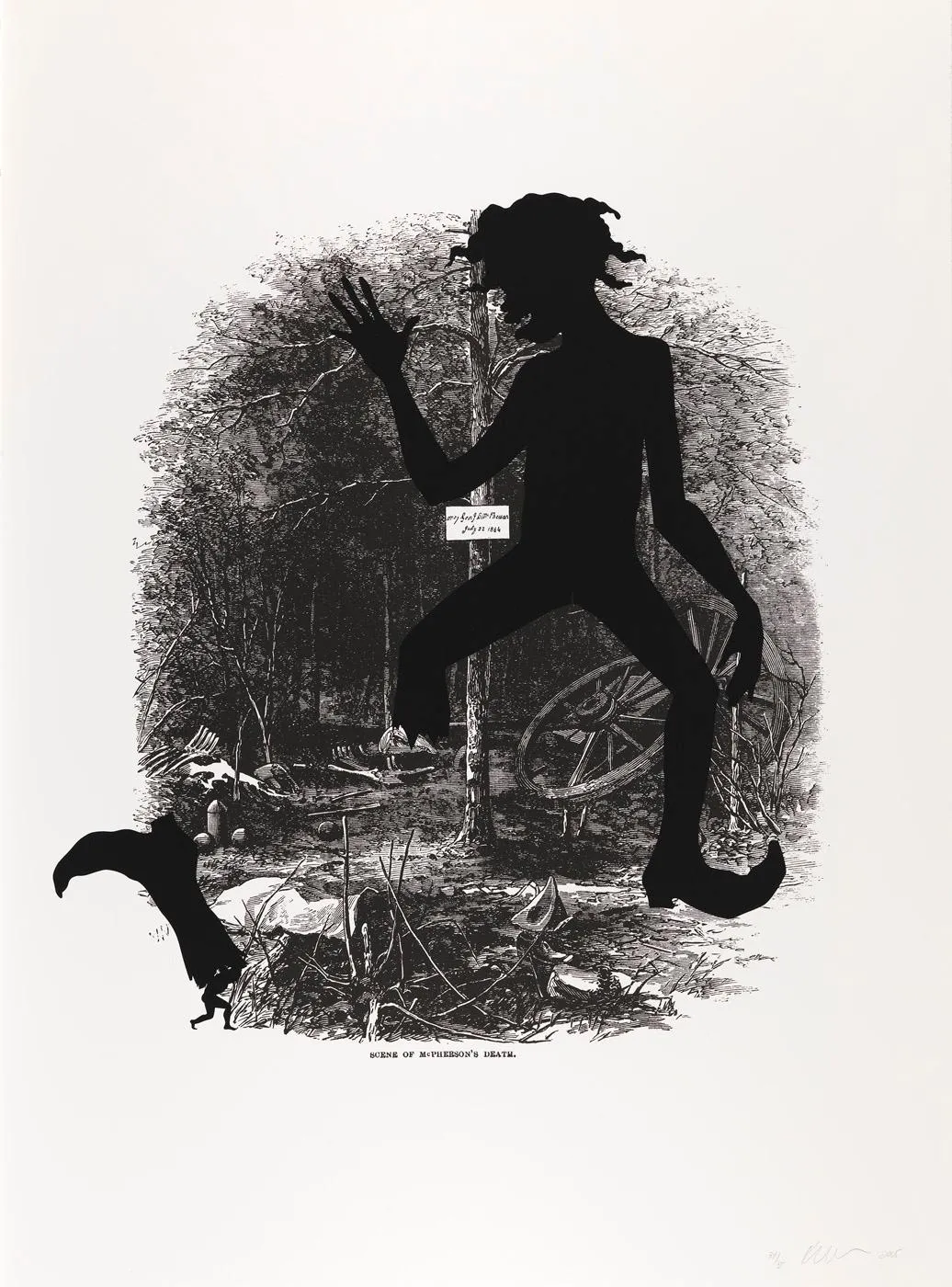

A new show at the Smithsonian American Art Museum entitled “Kara Walker: Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War (Annotated),” explores these twisted myths of slavery and the Civil War. Walker's signature imagery—surreal, often violent, sometimes absurdly sexualized silhouettes of African-Americans—depict not actual people, but characters based on racist caricatures once widely disseminated throughout popular 19th-century culture.

By superimposing these silhouetted figures onto blown-up reproductions of historic illustrations from Harper’s Magazine, Walker’s series of prints offers a low-tech augmented-reality version of once-current events.

Academics have long recognized that a definitive history, a completely unvarnished account of what actually happened during the Civil War, is unattainable. There are only different narratives, each determined by the concerns of the age in which it was created, each the product of the teller’s point of view.

In 1866, editors at Harper’s Magazine decided to sum up the Civil War with the publication of its two-volume, 836-page Harper’s Pictorial History of the Great Rebellion. The preface of the compendium bore an unusual statement of intent, which managed to sound both noble and milquetoast at the same time:

We purposed at the outset to narrate events just as they occurred; to speak of living men as impartially as though they were dead; to praise no man unduly because he strove for the right, to malign no man because he strove for the wrong; to anticipate, as far as we might, the sure verdict of after ages upon events.

Clearly, false equivalence has a long history; as does crafting a story to avoid offending readers. One striking thing about the illustrations in the Harper’s volumes is the degree to which battle scenes, fortifications, troops on the march, cityscapes and portraits of “great men” outnumber depictions of enslaved people, whose bondage motivated the war.

How should one respond to an account of history whose very presentation serves to enshrine a lie? Even today, this question remains central to American public discourse—relevant, for example, to the discussion of the removal of Confederate monuments.

Kara Walker’s response is to make it impossible to accept things at face value.

In the original Harper’s version entitled Alabama Loyalists Greeting the Federal Gun-Boats, a crowd of Union supporters swarms the river to meet the U.S. ships. In Walker’s update, a silhouette of an enslaved woman makes the most of the distraction, seizing the opportunity to run for her life. She commands the foreground; oblivious to her flight, the happy throng now provides the backdrop to her struggle for survival. Walker reveals a story that Harper’s leaves untold: regardless of the arrival of Northern forces, African-Americans remained in mortal peril, their lives and liberty at risk.

A unique aspect of the exhibition is that viewers are able to compare Walker’s prints to their source material. Nearby vitrines hold several editions of the Harper’s books.

Walker’s prints are not only larger but darker and heavier than the originals. In her version of Crest of Pine Mountain, Where General Polk Fell, the clouds in the sky are clotted with ink, threatening a storm, while Harper’s depicts a fine-weather day.

The original illustration has at its center four tree stumps, prominently lit, a would-be poetic evocation of loss. Walker’s version is dominated by a nude woman, her girth and her kerchief linking her to the “mammy” stereotype, lifting her arms to heaven as though in praise or lamentation. Behind her, a girl is ready to swing an ax. She aims it not at the tree stumps but at the plump leg of the woman. That she may soon be dismembered is suggested by another image in the series, in which a woman’s disembodied head, hand and breasts are flung on top of a battle scene.

The installation highlights one of the advantages of a museum that covers the entire history of American art. “Our ability to show these side by side, it makes the history come into relief and shows what the contemporary artists are actually doing,” says curator Sarah Newman. “It just makes both collections richer.”

When Newman arrived at the American Art Museum last year, having previously worked at the Corcoran Gallery of Art and the National Gallery of Art, she made her first order of business an extensive survey of the museum’s collection. Discovering that only two of the 15 of Walker's prints had been on view at the museum, she made plans to exhibit the entire series.

Walker came of age as an artist in the 1990s. By the time she received her Master of Fine Arts degree from the Rhode Island School of Design in 1994, she was already a force to be reckoned with—her knack for producing provocative work earned her a reputation early on. When she was named a MacArthur Fellow in 1997, at the age of 28, that reputation only grew, as she became the second-youngest person ever to be awarded the prestigious “Genius” grant.

Born in 1969, Walker is a member of Generation X, the product of a time when vanguard artists often deliberately muddied the waters of history, aggressively altering the stories we tell ourselves by imbuing them with many layers of meaning. Invariably, these layers stood in conflict with one another, and they regularly drew on elements of the outlandish, ironic and grotesque. Walker’s is a brutal and ugly dream world, in which events often make little rational sense.

“She feels like there’s no one way to represent African-American life or the African-American experience,” says Newman. “It’s always multiple, it’s always messy, and it’s always perverse.”

“The whole gamut of images of black people, whether by black people or not, are free rein in my mind,” she has said. (Walker herself rarely accepts interview requests, and through her gallery declined to be interviewed for this article.)

Walker’s art is not polemical. It doesn’t baldly speak its outrage and expect to receive in return only argument or assent. “I don’t think that my work is actually effectively dealing with history,” Walker has said. “I think of my work as subsumed by history or consumed by history.”

Artists much older or much younger than Walker often don’t understand her. Betye Saar, an African-American artist born in 1926, famously undertook a letter-writing campaign attacking Walker and trying to prevent the exhibition of her work. And in 1999, Saar told PBS, “I felt the work of Kara Walker was sort of revolting and negative and a form of betrayal to the slaves, particularly women and children; that it was basically for the amusement and the investment of the white art establishment.”

This fall, in advance of her show at Sikkema Jenkins, the New York gallery whose founder calls it “the house that Kara built,” Walker issued a statement. It reads, in part:

I know what you all expect from me and I have complied up to a point. But frankly I am tired, tired of standing up, being counted, tired of ‘having a voice’ or worse ‘being a role model.’ Tired, true, of being a featured member of my racial group and/or my gender niche. It’s too much, and I write this knowing full well that my right, my capacity to live in this Godforsaken country as a (proudly) raced and (urgently) gendered person is under threat by random groups of white (male) supremacist goons who flaunt a kind of patched together notion of race purity with flags and torches and impressive displays of perpetrator-as-victim sociopathy. I roll my eyes, fold my arms and wait.

In other words, she is taking the long view. Lyric Prince, a 33-year-old African-American artist, is having none of it.

In a column for Hyperallergic bearing the headline “Dear Kara Walker: If You’re Tired of Standing Up, Please Sit Down,” Prince scolds Walker for shirking her responsibility to artists who admire her, mockingly writing, “She’s well within her rights to just up and say: ‘Well, I’m going to paint happy little trees right now because this political climate is stressing me out and folks need to look at something beautiful for a change.’”

Walker, of course, did nothing of the sort. It's true that her New York show often departed from silhouettes in favor of more painterly or cartoonlike renderings. But the work is still every bit as complicated and panoramic, the imagery still as violent, sexualized, scatological and horrifying, as ever.

“When people say to [Walker] that she’s not representing the ennobling side of African-American life and she’s not being true to the experience, she’s saying, there’s no one true experience and there’s no one way to represent this,” Newman says.

“Kara Walker: Harper's Pictorial History of the Civil War (Annotated)” is on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum at 8th and F Streets, NW in Washington, D.C. through March 11, 2018

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Glenn_Dixon2.JPG)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Glenn_Dixon2.JPG)