I have a curatorial ritual that I have followed since I was a young curator at the California African American Museum in the 1980s. Whenever I create an exhibition I spend time walking through the gallery just prior to its opening to the public. This is my time to say goodbye, to reflect on the work and the collaborations that made the show possible. Once the public enters an exhibition it is no longer mine.

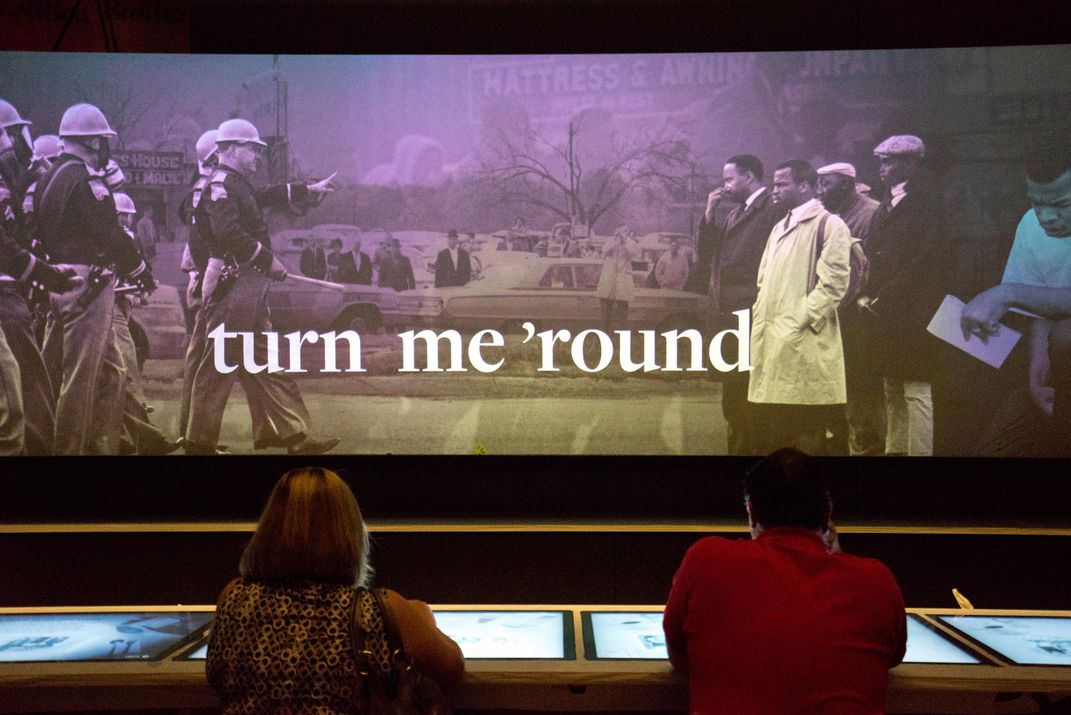

The impact, the interpretive resonance, and the clever (or so I hoped) visual juxtapositions are now for the public to discover. So, on September 16, 2016, the last day before a series of preopening receptions that would shatter the silence of creation, I walked through all 81,700 square feet of the inaugural exhibitions of the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC), saying my farewells and marveling at what we had created. I reveled in the 496 cases needed to house the collections, the 160 media presentations, the 3,500 photographs and images that peopled the galleries, the 3,000 artifacts winnowed down from 10,000 objects that were considered for exhibition, the 15 cast figures whose likenesses were eerily accurate, and the special typeface created for the museum by Joshua Darden, an African-American typeface designer.

I cried again as I was confronted by the exhibition that displayed the more than 600 names of the enslaved whose lives were forever changed by the separation of families and friends during the domestic slave trade that reached its apex during the 40 years prior to the start of the Civil War in 1861. And my sadness turned to anger as I read the names, once again, of the ships that transported so many Africans to a strange new world. But more than anything else, I simply said goodbye.

The creativity and effort needed to get to that day had been herculean. It had taken an army of designers, researchers, curators, educators, project managers and me. It was unusual for a director to take such an active role in helping to shape every presentation. I decided to put my fingerprints on every product, every publication, and every exhibition because I remembered something an exhibition designer had said to me during my tenure in Chicago. There was a desire to transform the Chicago Historical Society so it could be rebranded as a museum rather than a historical society. I hired a designer whose work had profoundly shaped my first major exhibition in Los Angeles, “The Black Olympians,” someone whose judgment I trusted. It had been a curatorial-driven effort and I set the tone but stayed out of the scholarly and content decisions. Several months into the design process the contractor came into my office and chastised me. He wanted to know why I was not helping my staff. “You are considered one of the strongest curators around but you are not sharing your knowledge and experience with your staff.”

His words stayed with me as we began to develop this museum’s exhibition agenda. I had years of curatorial experience and a keen sense of what makes engaging and essential exhibitions, which I vowed to share with my colleagues at NMAAHC. More importantly, I had a clear vision of what the exhibitions should explore, how they should educate and involve the visitors, and in what ways these presentations could bring a contemporary resonance to historical events.

I have often been asked if there was another museum that was a model for our efforts. There was no single museum that I could point to as one to emulate. There were, however, bits of exhibitions that informed my thinking. I had never forgotten the evocative and powerful way Spencer Crew’s work in his exhibit "Field to Factory" captured the small details of African-American migration, such as the child on the train with a basket of food that reminded the visitors that travel for African-Americans in the segregated South was fundamentally different from the same experience for white Americans. Or the manner in which the Holocaust Memorial Museum boldly embraced the challenge of exhibiting painful moments, such as a case full of shorn hair or the railcar that transported people to the death camps. I always think about the strangely titled museum in Beijing, the Chinese People’s Anti-Japanese War Resistance Museum, which had a contemplative space that encompassed hundreds of bells, as if each bell tolled for someone lost during the invasion of China. I learned much from Te Papa, the Museum of New Zealand, a cultural institution that used a few artifacts in a theatrical setting that spoke not of history, but of how people remembered that past and the ways those memories shaped national identity. And my own work in Los Angeles on the Olympics used cultural complexity and social history as ways to understand how the Olympics transcended sport. I also recalled how the exhibition curated by Gretchen Sullivan Sorin, “Bridges and Boundaries: African-Americans and American Jews” that was mounted at the New York Historical Society, embraced the challenge of interpreting the recent past such as the violent confrontations between blacks and Jews in Crown Heights, New York City.

I needed the exhibitions at NMAAHC to build upon the earlier creative work of other museums but not be held captive by prior curatorial efforts. My vision for the museum’s presentations was shaped both by philosophical concerns and the realities of being part of the wonderfully complex and imaginative Smithsonian Institution.

After reviewing the mountain of material contained in the audience surveys taken as part of the prebuilding planning, it was clear that the public had a limited understanding of the arc of African-American history. I felt that a portion of the exhibitions needed to provide a curated historical narrative. We found it necessary to provide frameworks that would help the visitor navigate the complexity of this history and also create opportunities for the audience to find familiar stories and events that made the museum more accessible, something that was reinforced by some of the criticism directed at the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI). Visitors at NMAI had been confused by the lack of a visible narrative that served to deconstruct and make the history of Native-Americans more comprehensible. I understood the scholarly reticence to craft an overarching framework narrative because that reduces the complexity of the past and privileges some experiences over others. In a museum, however, the audience searches for the clarity that comes from a narrative that offers guidance and understanding.

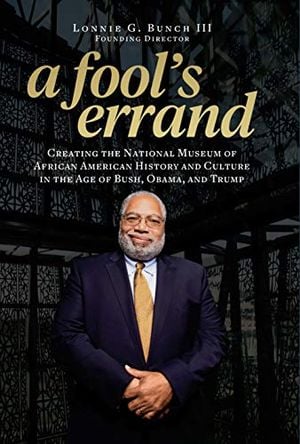

A Fool's Errand: Creating the National Museum of African American History and Culture in the Age of Bush, Obama, and Trump

This inside account of how Founding Director Lonnie Bunch planned, managed and executed the museum's mission informs and inspires not only readers working in museums, cultural institutions and activist groups, but also those in the nonprofit and business worlds who wish to understand how to succeed—and do it spectacularly—in the face of major political, structural and financial challenges.

I hoped that the exhibitions would also be cognizant of the tension between tradition and innovation. While I believed that the exhibits needed to be shaped by rich and interesting collections, I also understood that developing a museum in the 21st century meant that technology would cast a larger shadow than it had earlier in my career. Even though the collections would be a key element, we needed to embrace technology as a means to enrich the artifact presentations, provide opportunities to delve more deeply into the history we presented, and to provide ways for younger audiences to access the past through contemporary portals. The stories we explored should be comprehensive, with breadth and depth worthy of both a national museum and the history of black America: exhibits that placed issues of gender and spirituality at the heart of our exhibitions. I also challenged the staff to remember that the African-American community, that America, deserved our best efforts. To use a phrase from my college days, there would be “no half-stepping allowed.” Every aspect of the exhibitions had to reflect a commitment to excellence.

The exhibitions within NMAAHC presented a framework that sought to re-center African-American history and issues of race in the public’s understanding of America’s past. Usually Americans have traditionally viewed questions of race as ancillary episodes, interesting but often exotic eddies outside the mainstream of the American experience. Thus, it was important for the museum to demonstrate through its interpretive frameworks that issues of race shaped all aspects of American life: from political discourse to foreign affairs to western expansion to cultural production. And using both the scholarship that undergirded the exhibitions and the imprimatur of the Smithsonian, the museum could stimulate national conversations about the historical and contemporary challenges of race. Americans are sometimes obsessed with racial concerns, but the conversations tend to remain within their own communities. We hoped that NMAAHC could generate discussions across racial and generational lines that were meaningful, complex and candid.

The exhibitions that the museum hoped to create would use extensive storytelling to humanize history, to people the past in order to make the recounting of history more accessible and more relatable. By personalizing history, we wanted the visitor not to explore slavery, for example, as an abstract entity but to experience it as a way to learn to care about the lives of those enslaved, those who had hopes, shared laughter and raised families. For the presentations to be successful they had to give voice to the anonymous, make visible those often unseen, but also provide new insights into familiar names and events.

Thanks to advice from people like Oprah Winfrey, we knew that the stories must be accurate, authentic and surprising. That is why the museum exhibitions would make extensive use of quotations and oral histories that would let the voices of the past, the words of those who lived the experiences, drown out or at least tamp down the traditional curatorial voice. It was also essential that the stories the museum featured reflect the tension between moments of pain and episodes of resiliency. This must not be a museum of tragedy, but a site where a nation’s history is told with all its contradictions and complexity.

I also wanted the exhibitions to have a cinematic feel. As someone who revels in the history of film, I needed the visitor to find presentations that were rich with drama, cinematic juxtapositions, with storylines that elicited emotional responses and interconnectivity so that the whole museum experience was a shared journey of discovery, memory and learning.

I believed that my vision would enable the museum to make concrete a past often undervalued. But even more important was the need for the exhibitions to help all who would visit understand that this museum explored the American past through an African-American lens in a way that made this a story for all Americans. Ultimately, the exhibition must fulfill Princy Jenkins’s admonition by helping America remember not just what it wants to recall but what it needs to remember to embrace a truer, richer understanding of its heritage and its identity.

This was an ambitious and challenging proposition, especially for the small, initial core team of Tasha Coleman, John Franklin, Kinshasha Holman Conwill and the recently hired curators Jackie Serwer and Michèle Gates Moresi in 2006. This group would meet daily in a conference room lined with large sheets of yellow paper where we wrote down every idea, every hope and every challenge we had to overcome. The biggest hurdle was the need to plan and later design exhibitions without a significant artifact base to draw upon. The best we could do was to draft broad exhibition topics that the museum needed to address—slavery, the military, labor. We could not finalize the specific interpretations and directions until we obtained collections that carried the stories we felt were important. In essence, crafting the exhibitions, much like every aspect of this endeavor, felt like we were going on a cruise at the same time as we were building the ship. Everything was in flux and all our best ideas remained tentative. From the very beginning we all had to be comfortable with an ambiguity that complicated our efforts.

We also had to find ways to distill the five decades of scholarship that emanated from the work of generations of academics whose research had made the field of African-American history one of the most vibrant and extensive areas of study in universities. How did we guarantee that our exhibitions reflected the most current scholarship? And how did we navigate the ever-changing interpretive debates? What kind of exhibitions were needed if we were to help Americans grapple with their own culpability in creating a society based on slavery, or a nation that accepted segregation as the law of the land? We quickly realized that starting with nothing but a dream was liberating and unbelievably frightening. The ultimate success of our exhibition efforts was dependent upon the nimbleness of the growing curatorial and educational staff, the organizational and planning capabilities of the museum’s Office of Project Management (OPM), and the collaborations that were forged with our university colleagues.

Academics are usually described as the smartest kids in the class who never learned to play well with others. This was not the case during the creation of NMAAHC. I was gratified by the generosity of the scholarly community. While I always assumed I could depend upon the many friends I made in universities, the positive responses and the willingness to help a project that all saw as important was overwhelming. Almost no one refused our calls for help. Political and scholarly debates were an element of this work, but those disputes were usually set aside for the good of the museum. Very early in this process I wrestled with how the museum should interpret slavery. I believed that exploring the “Peculiar Institution” (a 19th-century name for slavery) was essential for an America still struggling to embrace the history and the contemporary resonance of slavery. During a discussion with Alan Kraut, one of my former history professors at American University, we focused on my commitment to presenting a major exhibition on slavery that explored the lives of the enslaved and the influence slavery had on antebellum America. Kraut solved my dilemma when he said simply: “The framework should be slavery and freedom.” His suggestion made clear the duality of the African-American experience that the museum needed to explore; it was both a fight for freedom, fairness and equality; and it was the challenge not to define Black America as simply a source of struggle.

The most consistent and important academic vehicle that shaped NMAAHC was the Scholarly Advisory Committee (SAC) that was created in 2005. On paper, it was formed to provide intellectual guidance and be a conduit to the best scholarship coming out of universities. Chaired by John Hope Franklin, the revered dean of African-American historians, SAC was the Smithsonian’s way to shield the nascent museum from criticism that scholarship was not at the heart of the endeavor from its inception. It is true that SAC was the intellectual engine, along with the curators, of NMAAHC. Yet SAC was so much more. It was a cauldron of scholarship and camaraderie that made our ideas better and brought forth new insights and interpretive possibilities.

Just being with John Hope Franklin was a learning experience for everyone in the room. I felt blessed, a word I do not use lightly, to sit next to John Hope during those meetings. I had always regretted not being one of his graduate students, but now I was given the chance to learn, to be schooled by one of the most gifted and well-known historians of the 20th century. As a child, whenever the family dined together, my father would discuss issues that he thought we should understand. I don’t remember how old I was when he spoke about a history course he had taken at Shaw College in the 1940s and how impressed he was with the writing of someone named John Hope Franklin. I am sure that he was the only historian my scientist father ever mentioned to me. I felt as if my father was with me as John Hope whispered ideas and historiographical concerns that only I heard. John Hope guided and prodded the group—and the museum—to find ways to tell the unvarnished truth and to use African-American history as a mirror that challenged America to be better, to live up to its ideals. John Hope’s presence and authority inspired us all to do work worthy of the career and spirit of this groundbreaking historian. He committed the final years of his life to the museum and I would do everything possible to ensure that his efforts were rewarded by a museum that honored his life and legacy.

In addition to John Hope, SAC was a gathering of leading historians like Bernice Johnson Reagon, Taylor Branch, Clement Price; foremost art historians, such as Richard Powell, Deborah Willis and Alvia Wardlaw; innovative anthropologists and archaeologists, including Johnnetta Betsch Cole and Michael Blakey; and educators of the likes of Drew Days, Alfred Moss and Leslie Fenwick. I guess the best way to describe the intellectual energy, the vibrant and candid discussions, and the spirit of fellowship and collaboration that was evident at every one of those gatherings is to say that attending a SAC meeting was like a wonderful Christmas gift that made you smile and made you better. These were exceptional scholars who became close friends and who gave of their time—attending three or four meetings annually—and shared their life’s work. For all of that, their compensation was our gratitude and the knowledge that NMAAHC would not exist without their generosity. The ideas that flowed from those sessions were reflected in many of the curatorial decisions that would shape the inaugural exhibitions. We discussed every aspect of history and culture, including the difficult task of filtering out stories, individuals, and events that, though worthy, could not be included in the exhibitions. These discussions were passionate and candid but always respectful and productive.

At each meeting, a curator or myself would present exhibition ideas and later complete scripts for discussion. I can still feel the heat from Bernice Johnson Reagon whenever she felt that issues of gender were not as central as they needed to be. I smile when I recall the carefully considered and gentle prodding of my dearest friend Clement Price as he reshaped our interpretation of postwar urban America. Michael Blakey and Alvia Wardlaw spent hours pushing us to embrace artistic and archaeological complexity more fully. And Alfred Moss made sure that our notions of religion and spirituality encompassed a diversity of religious beliefs and practices. Our ideas sharpened as Drew Days and Taylor Branch helped us see the subtle nuances at work during the Civil Rights Movement.

As a result of one SAC meeting, the museum discovered a phrase that would provide the glue to bind together every exhibition we would create. Johnnetta Cole and Bernice Johnson Reagon responded to a curatorial presentation that sought to examine the manner in which change occurred in America by referring to a biblical quotation in Isaiah 43:16. “Thus saith the LORD, which maketh a way in the sea, and a path in the mighty waters.” Which meant that God will make a way where there seems to be no way. That idea, of making a way out of no way, became not only the title of the proposed exhibition, but also a way to understand the broader African-American experience. Almost any story that the museum exhibited ultimately revealed how African-Americans made a way out of no way. Despite the odds and the oppression, blacks believed and persevered. Making a way out of no way was more than an act of faith, it was the mantra and the practice of a people.

In time, every curator and educator presented to SAC. SAC nurtured the staff with tough love. Often the precepts of the presentations were challenged and occasionally rejected, but the staff was better for the experience. And the final exhibition products were finely tuned and highly polished after undergoing what I called the “SAC touch.”

The Scholarly Advisory Committee was our rock for more than a decade. We counted on their guidance and on their candor and even their criticism. The work of SAC was buttressed and expanded by an array of historians who also contributed to the shaping of the museum. I wanted the curators to experience the differing interpretations of African-American history so that their work was placed within those scholarly contexts. We accomplished this by participating in what I called “dog and pony” shows with colleagues around the country. I wanted to benefit from the diverse scholarly voices within university history departments. I contacted close friends and asked if they would organize a day where the curators and I would come to campus to discuss the museum’s vision, our interpretive agenda, and explore the exhibit ideas that we were developing. All I asked for were a few bagels and a lot of critical conversation.

Among the many campuses we visited, I was so appreciative of Edna Medford who organized our sessions at Howard University; Eric Foner at Columbia; Jim Campbell at Stanford; and David Blight who agreed to host our very first meeting at Yale University. Our gathering in New Haven included historians, literary scholars, folklorists and political scientists. The staff presented the tentative exhibition ideas to the group and then David Blight and I facilitated the discussion. So much was revealed during that day: how we needed to broaden our definition of culture; how central the use of literature would be to give voice to the history, and how important it was for the nation that the museum craft a complex yet accessible exploration of slavery. At Howard University, we wrestled with interpretive frameworks that would introduce our audiences to the intricacies of interpreting the Atlantic world and the continuing impact of the African diaspora on the United States. Edna Medford and her colleagues at Howard pushed the museum to find ways to examine how the recent migration of Africans to America, since the 1970s, that now outnumbered the total of Africans transported to the states during the era of slavery challenged our assumptions about the African-American experience.

At Columbia University, my friend Eric Foner and his colleagues emphasized the need for the exhibitions not to shy away from either complexity or controversy. While much came from that meeting what I remember most was the presence of the late Manning Marable. Marable’s work has enriched the field of African-American history and I knew the museum would benefit from his contribution. What I did not realize was just how sick he was at the time. Despite his illness, he wanted to participate because, as he said to me: “I will do anything I can to help this museum create exhibitions that illuminate a history that is often misunderstood and underappreciated.” Manning’s presence reminded us what was at stake and how important our work was to scholars and to America.

The commitment of Manning Marable was echoed throughout the university community: preeminent scholars and professors just beginning their careers all offered their time and expertise to ensure that “the museum got it right.” As the ideas and topics for the museum’s presentations began to solidify, each exhibition curator (there were 12 by 2015) had to present to me a group of at least five scholars who would work to help develop the shows. In essence, each exhibition would have its own scholarly advisory body to guarantee the academic integrity that was essential to our success. Ultimately, more than 60 historians in addition to SAC worked directly with the museum.

The culmination of that support came at a conference that James Grossman, the executive director of the American Historical Association, and I organized, "The Future of the African-American Past," in May 2016. This gathering was planned to be the first major event in the completed building on the Mall, but the realities of construction forced us to house the conference in my former home, the National Museum of American History. This symposium was both an opportunity to revisit a groundbreaking three-day conference in 1986 that assessed the status of Afro-American history, and to position NMAAHC as the site, generator and advocate for the current state of the field.

This conference was a signature moment because I wanted my university colleagues to view this new museum as an essential partner and an opportune collaborator whose presence helped illuminate their work. I was humbled when the field embraced these sessions and this museum. Thanks to the creativity and connections of James Grossman, we were able to organize panels that explored, for example, the long struggle for black freedom, the changing definition of who is Black America, the evolving interpretations of slavery and freedom, race and urbanization, capitalism and labor, and the role of museums and memory. When I arose to speak at the session exploring the state of museums, I was stunned to behold a standing ovation from my university colleagues. This meant so much, not just to me but to all historians who labor in museums and in fields outside of the university. Early in my career, those labeled “public historians” were considered second-class citizens, academics who could not make it in the academy. Though attitudes slowly changed, this positive embrace by the totality of the profession, I hoped, signaled a new and greater appreciation for educational reach and public impact of those who are not university professors.

The guidance provided by SAC, the university history departments that hosted the museum visits, the scholars associated with specific exhibition ideas, and the reams of data gleaned from audience surveys and focus groups all influenced our decisions about what displays to mount. The final determinations were made by the curators, educators, and myself as to what exhibitions would grace the galleries of NMAAHC and present our interpretations of history and culture to the millions who would eventually come in contact with the museum. We decided that we needed a historical narrative, within a space designated as the History Galleries, which would guide the visitor’s experience and provide a foundation for the rest of the museum presentations. This narrative would begin at some point prior to the creation of the American colonies and continue into the 21st century. There were many questions to be answered. Should the exhibition start in Africa? How should slavery be remembered and interpreted? How should racial and sexual violence be presented? How hopeful should the exhibition be? And how does the museum ensure that the exhibitions are not seen simply as a progressive narrative, a linear march to progress?

We then determined that we needed a floor of exhibitions that explored community. Here it was necessary to examine the regional variations of African-American life. But we also wanted to explore the history of African-Americans in sport and within the military through the lens of community as well. Most importantly, we needed to create an exhibition that responded to a notion that appeared quite consistently in our audience research: the inevitability of racial change and progress. We had to find ways to help our visitors understand and problematize just how change happened in America and that nothing was inevitable, not freedom, not civil rights, not economic mobility. The third gallery would be dedicated to an exploration of the diversity of African-American culture. It was important to frame culture as an element of the creativity of a people but also as a bulwark that empowered African-Americans and helped them to survive and even thrive despite the racial strictures that were a constant reminder that all was not fair and free in America. This floor would house exhibitions that explored African-American music, featured African-American fine art, examined the role occupied by African-Americans in the performing arts of film, theatre and television. All of these presentations would be contextualized by a major exhibit that looked at the various forms of cultural expression from foodways to speech to fashion and style.

As with all the galleries, the challenge would be how to determine what aspects of this history to omit due to spatial concerns or the lack of an artifactual presence. As the son of two teachers and the spouse of a museum educator, I believed the museum also needed to dedicate significant square footage to our educational agenda. We wanted a floor that would contain classroom space, technologically sophisticated and yet accessible interactives that would broaden our ability to service a variety of learning styles, and an area that would house a center that aided visitors with genealogical research. Additionally, because of the uniqueness of both the building and the long saga of the museum, I needed a modest presence somewhere in the museum that deconstructed the structure and shared the process of creation.

There was to be one other interpretive space within the museum. I had always been impressed with the Mitsitam Café within the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI). That museum had made a brilliant use of the restaurant by serving Native-American cuisine from a variety of regions: buffalo burgers from the Southwest, clams from the Northeast. NMAI used the café as part of the way it introduced visitors to the diversity within the native communities. I borrowed freely from their creation. I wanted a café within NMAAHC that would use food to emphasize the regional variations within black America. I sought to turn the entire café into a family friendly interpretive space that would explore the role and the preparation of food in African-American communities. Yet this would be more than a living gallery, it would also serve exceptional cuisine. After all, if visitors to the Smithsonian were willing to pay $15 dollars for a mediocre hamburger, why would they not spend the same amount for shrimp and grits or chicken smothered in gravy?

While the curatorial and scholarly discussions helped to determine the types of exhibitions the museum would display, answering many of the questions we raised and determining the exact flow, pacing, placement and look of the exhibitions required a team of exhibition and graphic designers with the capacity to handle such a massive endeavor and the courage and creativity to help us be bolder than we could have imagined. Initially I wanted to hire three distinct design teams, each assigned to either the history, community or culture gallery. I worried that the visitors exploring so many galleries would experience “museum fatigue.” Having three different teams designing distinct spaces would, I hoped, energize and not tire out our audiences.

Lynn Chase, who oversaw the Smithsonian Office of Project Management, argued that having three independent design firms would be a logistical and contractual nightmare. Working through the contracting bureaucracy of the Smithsonian, she suggested, would add years to this endeavor as the federal process would be a drag on my need to move quickly. Lynn was right. I eventually trusted Ralph Appelbaum Associates (RAA) with this crucial task. To many outside of the museum, hiring the architectural team to design the building was the most important decision I would have to make. I disagreed. Bringing on the designer who would work closely with a large team of educators, curators, collection specialists and project managers to produce the exhibitions upon which the reputation of the museum rested was my most significant and thorniest decision.

RAA had a history of designing exhibitions on the scale and the importance of those we envisioned at NMAAHC, including the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., the Canadian Museum for Human Rights in Winnipeg, and the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia. Yet I was hesitant. I knew that RAA had mastered the creation of 20th-century exhibitions, but I was unsure if the firm could help the museum identify and address the challenges of audience and technology that would be at the heart of the 21st-century exhibition development. As a result of some preliminary interaction with the firm’s principal, Ralph Appelbaum, RAA developed an impressively diverse team that included millennials whose comfort levels with issues of race and interest in embracing a multigenerational audience convinced me that our partnership could produce memorable work.

Though the process benefitted from the insight and presence of Ralph Appelbaum, our group worked closely with Melanie Ide who led the design team. Each exhibition was assigned a museum team that included curators, historians, project managers and educators. They worked with RAA to identify storylines, interpretive goals, key artifacts in the museum’s collections and the visual look of the exhibition. There were literally hundreds of meetings, dozens of staff and thousands of pages of ideas and drawings that slowly sharpened the focus of the exhibitions.

Unless I was on a fundraising journey, I tried to attend many of the meetings. I participated in the discussions helping to shape the character and the content of the specific exhibitions, but I also needed to provide oversight as to how the totality of our exhibition program fit together. This was a challenging process that was both exhausting and exhilarating. Part of the dilemma was that the curators had varying degrees of exhibition experience, which either slowed the development efforts or often allowed the designs to move in directions that were unsatisfactory. I know that it frequently frustrated the curators, but I intervened whenever I thought the exhibition designs did not reach the levels of excellence and creativity that we needed. To achieve the quality I wanted, the curators and designers had to become comfortable with revision after revision until I felt we had crafted an excellent exhibition that was visually engaging and educationally rich.

In working together for so many years with competing needs and the pressures of schedule, there were bound to be moments that were tense and testy. RAA needed closure so the process could move forward, while the museum staff needed flexibility because they were still developing the curatorial posture and the acquisition of collections. The issue of the artifacts needed to finalize the design packages caused much consternation.

NMAAHC had to find collections as the exhibition designs were being finalized in the meetings with RAA. Waiting to confirm the list of collections was, at times, infuriating to both sides. We agreed that we would include objects from “a wish list” in the initial exhibition design. As the material was collected, the “wish list” became the actual list. We agreed that we would set deadlines for each of the exhibitions and once the deadline passed the design would encompass only the artifacts actually in the museum’s holdings. This put inordinate pressure on the curatorial team because they had to shape and reshape their work based on unearthing collections that we hoped could be found in time to have an impact on the design process. Usually we accepted the concept of the deadline. There were artifacts, found late in the process, that I demanded be included. The design package for the "Slavery and Freedom" exhibition was 90 percent completed when the curators found a stone auction block from Hagerstown, Maryland, where enslaved African-Americans were torn from family and friends and examined like animals. This painful and powerful artifact was too important to omit, so RAA adjusted their plans, not without concern, but they recognized that they had to be flexible if we were to create the best products possible.

Despite the tensions, the brilliance and the creativity of RAA, thanks to the leadership of Ralph Appelbaum and Melanie Ide, led to an inspired design that created moments of wonder and inspiration. Shortly after the design meetings began in 2012, Ralph asked if we could meet to discuss a serious issue. I was surprised. It was too early in the process to be at a crisis point. Ralph understood that the museum needed to provide an in-depth overview of African-American history. He posited that if we were to accomplish that goal, the History Gallery, located just below ground, needed to be expanded, from one level into a three-tiered exhibition experience. Ralph brought drawings that provided a better sense of what he was proposing. I was intrigued, but concerned that this idea would be a casualty due to the fact that both the architectural and construction planning was six months ahead of the exhibition development. This difference was caused by our inability to hire the exhibition design team until I raised the money to offset the costs. I was unsure of what to do. I had always said that you only get one shot to build a national museum—so the museum, in other words, me—should be bold and do what is right. This was one of the riskiest decisions I would make during the entire project. Do I make changes that will slow the process of design and construction? Will it look as if I would change directions and earlier decisions on a whim? And was this a decision that I wanted to expend a great deal of my personal capital on this early in the building process?

I immediately met with the architects to gauge their reactions and assuage what I knew would be their fears about unplanned revisions because they would have to alter the design of the building foundation to account for the added depth that this change would require. During the discussions I could see that David Adjaye and Phil Freelon were apprehensive: did this action signal other changes that would need to be made to accommodate the design of the exhibitions? There were concerns about cost and schedule, but I believed we could find a way to make this work. So, I forced this fundamental change, which ultimately transformed the exhibition strategy within the building. To the architects’ credit, they saw the possibilities of Appelbaum’s ideas and soon shared my enthusiasm, just not to the same degree. I realized that if I was the museum’s director then I had to lead, to do what I thought would strengthen the museum and give the public, especially the African-American community, an institution worthy of their struggles and dreams.

Today, the tiered History Gallery is one of the most distinctive features of the museum. I cannot imagine what the gallery experience would be if we had been forced to limit the content and collections to only one floor. As a result of this adaptation, the exhibitions convey a sense of rising from the depths of the past to a changed present and a future of undefined possibilities. This was the correct decision. There would be costs, both financial and political, but that was yet to come.

I was impressed with the ideas, large and small, that RAA brought to the design. RAA’s use of entire walls emblazoned with the names of individuals affected by the domestic slave trade and the listing of the data about the ships that carried the enslaved during the brutal Middle Passage gave a sense of humanity and a better understanding of the scale of the international slave trade.

The presentation was enriched by the display of the artifacts from the slaver, the São José, which would enable the visitor to understand this history through the story of the enslaved on a single vessel. RAA’s creativity and sophisticated design aided the museum in its desire to make difficult stories of the past more meaningful and accessible to those who would one day explore the history we presented. And the idea to create vistas throughout the History Galleries so that the visitors would understand how the spaces, whether it was “Slavery and Freedom,” “The Era of Segregation,” or “1968 and Beyond,” were all interrelated. The use of dates on the elevator shaft walls that assisted the audience’s transition back to the 15th century was another example of their imaginative design.

RAA’s creativity is apparent throughout the museum. For example, in the sports gallery on the third floor the use of statutes of athletic figures like Venus and Serena Williams or the manikins that capture the Black Power Olympics of 1968 not only reinforce the interpretations within the gallery but they also provide visitors with opportunities for selfies that document their visit to the museum and place them in history. Simple touches, such as exhibiting George Clinton’s Mothership as if it were floating much like it appeared during the group’s concerts, or the directional use of music throughout the galleries to aurally place the visitor in a specific time or place all contributed a great deal to the overwhelmingly positive reactions the exhibitions have received.

One area of the design that meant a great deal to me was the creation and implementation of the reflection booths. I had never forgotten how moving the stories were that we captured as part of our collaboration with Dave Isay and the StoryCorps Griot Program. I wanted to have a space where families could reflect not just on their museum visit but on their own history. RAA designed these booths with simple prompts that allowed the user to record stories about their families, the meaning of African-American culture, or the reasons why they chose to spend time at NMAAHC. These recitations became an important part of the museum’s archives and an opportunity to reinforce our commitment to sharing the stories of the past that are often little known.

Not every idea that RAA developed made a successful contribution to the exhibitions. The curators wanted to contextualize the stories that were in the History Galleries by using the words and images of the generation explored in the space. The placement of these reflections of a generation were not conducive to engaging the audience, nor did the design strengthen an idea that was, candidly, underdeveloped from a curatorial perspective.

We spent weeks grappling with a design idea that was supposed to capture the feel of battle during the American Revolution and during the Civil War. These interventions, eight feet long and four feet in depth, were designed to create a movie set-like feel with props (not actual historic objects) that would provide the audience with a sense of what battles were like during these two wars. These pits were a compromise because the museum’s interpretation of both the Revolutionary and Civil Wars downplayed the actual battles in order to explore the social and cultural impacts of these two key moments in American history: how the Revolutionary era began a process that emboldened the antislavery sentiment in many Northern states and how the Civil War was a watershed moment that changed the tenor and tone of America by enabling the conditions that led to the emancipation of four million enslaved African-Americans. Other than a media overview that simulated the feel of war, we never settled on the effective use of those spaces. And the final design resembled an unexciting re-creation of a re-creation. It is one of the few aspects of the final exhibition installations that was unsuccessful.

That said, the collaboration between NMAAHC staff and the team from RAA worked well, if the final product is any arbiter of success. While a great deal of the credit belongs to RAA, my colleagues at the museum were equal partners whose ideas and whose scholarship challenged RAA and in the end created a set of exhibitions driven by a strong curatorial vision that engaged, entertained and educated.

Another unit in NMAAHC deserves much of the credit for this successful collaboration, the Office of Project Management. From the beginning of the creation of the museum, I knew that our ability to handle the myriad of tasks and issues that had to be addressed would determine the success or failure of our work. I believed an office that could coordinate and manage the tasks that emanated from the challenges of construction, exhibition design, curatorial and collections concerns, and object installation was an urgent necessity. To create this essential function, I turned to Lynn Chase, a no-nonsense colleague, who had worked with me for 13 years at the National Museum of American History. She had managed significant projects while at NMAH, including the 19th-century exhibition and the traveling version of another exhibition in which I was involved, “The American Presidency: A Glorious Burden.” During my last years at NMAH, Lynn worked directly for me as my de facto chief of staff. Her ability to organize large-scale endeavors and her willingness to confront me over the years when she thought I was wrong convinced me that she was the person I needed. Under Lynn’s leadership, talented project managers like Carlos Bustamante and Dorey Butter joined our growing staff and brought order and systems that helped in our organizational transition from a start-up to a full functioning museum.

I cannot overstate the value that Lynn and her colleagues brought to the museum’s ability to identify and address the myriad of hurdles that we faced. Working with RAA, the Office of Project Management coordinated—and sometimes changed—individual calendars so that the hundreds of design meetings could be scheduled. OPM did more than schedule the assemblies: they shaped the agendas, prepped the participants and illuminated areas of debate that needed to be confronted. The OPM team was the fuel that allowed these gatherings to be productive. A large part of their work was the gentle prodding of all the participants from the curators to RAA’s designers to confirm that progress was being made. No one was spared from the pressure to meet deadlines and make some headway no matter how incremental. And that included the director. Almost every day, Lynn would march into my office with a notebook full of issues and challenges that required my attention, my consent, or my curatorial experience. While there were times that I wanted a respite from Lynn’s laser-like focus and intensity, I knew that her commitment to the museum and to me guaranteed that we would build the museum of my dreams. I am sure that without Lynn and her colleagues the process of design would have slipped and delayed the opening of the museum by several years. The efforts of the curators and the designers would receive most of the acclaim and attention, but the unsung heroes were the staff of OPM. They not only believed in the vision, they actually knew how to implement it.

A Fool's Errand: Creating the National Museum of African American History and Culture in the Age of Bush, Obama, and Trump

This inside account of how Founding Director Lonnie Bunch planned, managed and executed the museum's mission informs and inspires not only readers working in museums, cultural institutions, and activist groups, but also those in the nonprofit and business worlds who wish to understand how to succeed—and do it spectacularly—in the face of major political, structural, and financial challenges.

The use of media was another factor in the successful interpretation of the African-American past within the museum. RAA wanted the shaping and the production of the nearly 140 media pieces that enlivened the exhibitions to be under their direction. That would make a seamless relationship between the exhibition design and one of the most visible interpretive elements in the galleries. I decided to move in a different direction, though. I did this partly for reasons of budget but also for my own comfort level. As I have done so often in my career, I turned to someone from my past to help me overcome a particular problem. I contacted one of America’s most talented producers, Selma Thomas, who I think is the queen of museum filmmaking. Selma has either made or produced some of the most important film work in American museums, including pieces that captured the Japanese-American experience as part of the exhibition "A More Perfect Union: Japanese Americans and the U.S. Constitution." Selma also produced films for the National Gallery of Art, the Franklin Institute and the National Museum of American History, where she developed several projects for me, among them the American Festival in Japan.

Knowing that media was both a way to tell more complex stories within exhibitions and to attract younger audiences often drawn to film, I needed leadership that would help the museum craft media presentations that were integral to the interpretation of the exhibition subject. I had never been involved with a project that was so media rich. Selma’s job was to help the curators and RAA decide what aspects of the history would be best explored through media, and how much would rights issues limit our use of the medium. She was also in charge of overseeing the production so that the final product reflected the initial concept.

Complicating those tasks was the decision to work with the Smithsonian Channel. Initially my thoughts had been to work with the History Channel, a known entity that had produced films for me as early as 2000. In 2014, I was approached by the Smithsonian Channel. They were excited about the branding opportunities associated with the newest Smithsonian museum and offered to create all the media pieces we needed. Ultimately, that proposal swayed my decision. Its great appeal: it provided significant budget relief as the channel would bear all costs. Selma, then, had to be my liaison with the channel and evaluate every script and rough cut to maintain the quality and the interpretive clarity the museum demanded.

For the next two years, Selma attended design meetings, nurtured curators who had limited exposure to the medium of film, wrote concepts and rewrote treatments from the Smithsonian Channel that sometimes failed to meet our needs, oversaw research in film archives, and provided direction as each film was being developed. Selma raised issues that needed my attention. As a result, I also reviewed every media piece that would one day be shown in the museum. At least the days of half inch tape using unwieldy film and slide projectors were long gone. Selma would send me links to the films to my computer and I would then email her my comments to share with the directors hired by the Smithsonian Channel.

Working with the Smithsonian Channel was not without hurdles, such as the need to have many more editing sessions than they normally do because of the museum’s insistence that the films find a way to make complexity accessible and that the media pieces be shaped mainly by the curatorial vision. I do not want to downplay the contributions of the Smithsonian Channel. Their willingness to adjust their television-based procedures and goals in order to craft products that worked within the exhibition framework was both a challenge to them and a key to the successful media pieces that enriched the visitor experience. I am still enthralled every time I view the monitor that documents the enthusiasm and pride of the music created by Motown. And my mood always saddens when I view the media piece that captured the hatred and the casual bigotry of the 1920s by showing the footage of thousands of members of the white supremacist organization, the Ku Klux Klan, being embraced and celebrated as they marched through the streets of the nation’s capital. Thanks to the Channel’s skill and Selma’s attention to detail and to quality, the films within the museum are part of that mosaic of image, word and object that allowed NMAAHC to present a complicated yet accessible history.

Museums are at their best when the collaboration among designers, curators and educators sharpens the interpretive and visual edges of the exhibitions, making the past accessible in a way that provides both emotional and intellectual sustenance. The partnership with RAA enabled the museum to tell, in John Hope Franklin’s words, “the unvarnished truth.” Or in the words of a visitor who stopped me as I walked through the museum one day and thanked me for exhibitions that “do not shy away from the pain but dull that pain by celebrating the wonders of a community.”

This article was excerpted from A Fool’s Errand: Creating the National Museum of African American History and Culture In the Age of Bush, Obama, Trump by Lonnie G. Bunch III and published by Smithsonian Books.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5d/1e/5d1e50b3-6784-42dd-a26b-ea7d12f7dbcc/2016-05542.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lonnie_new1.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lonnie_new1.jpg)