How ‘Moonlight Serenade’ Defined a Generation

Bandleader Glenn Miller, who was lost at sea 75 years ago, played and replayed the song before troops serving in World War II

:focal(2374x1506:2375x1507)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/53/47/53472f73-7f58-4293-8e0b-b97493817ac2/nov2019_e13_prologue.jpg)

At 1:45 p.m. on December 15, 1944, an overcast Friday afternoon at the Royal Air Force airport near Bedford, England, U.S. Army Maj. Glenn Miller struggled against the stinging airstream blowing in his face from a running propeller as he threw his briefcase and military garment bag into the cabin of an idling airplane. The single-engine C-64 Norseman, piloted by Flight Officer John R. S. Morgan, was aloft in minutes, and Miller, the bandleader whose mellifluous swing provided the soundtrack for Americans during World War II, was on his way to an airfield near Versailles, France.

Miller and his American Band of the Allied Expeditionary Forces had been making appearances in England since early July. Now military authorities wanted the orchestra to entertain troops on the Continent. Determined to fly ahead and finalize tour arrangements, Miller told his brother in a December 12 letter that “barring a nosedive into the Channel, I’ll be in Paris in a few days.”

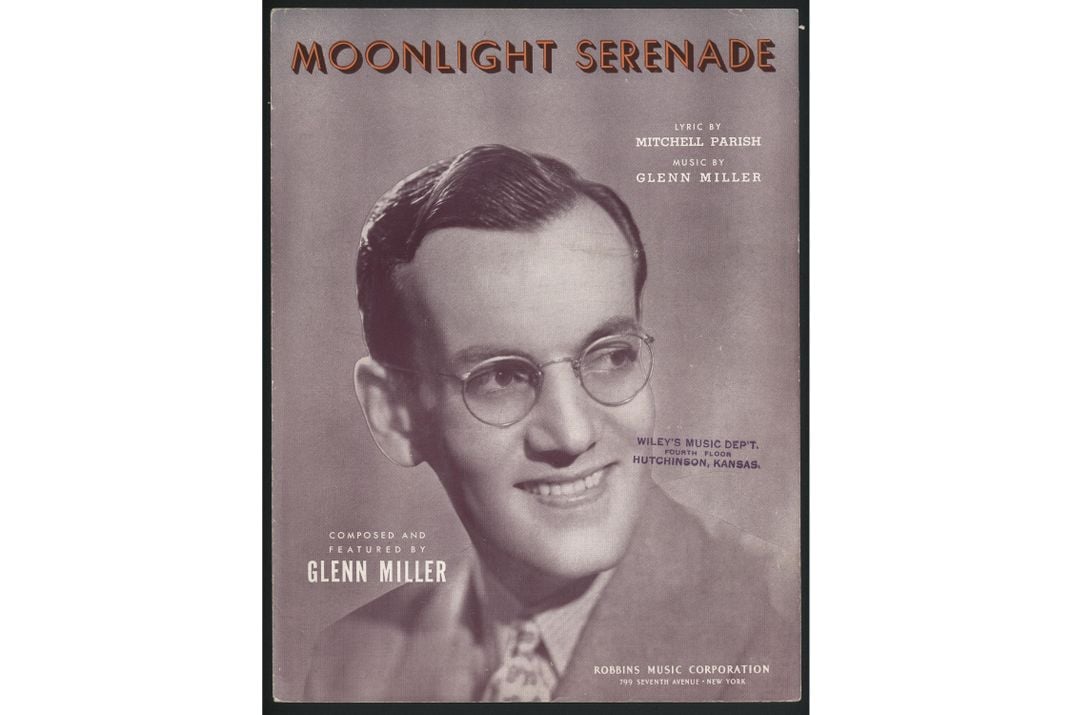

The G.I.s looked forward to no tune more than “Moonlight Serenade,” the ever-so-slightly melancholy number evocative of a sultry summer night back home. It served as the orchestra’s theme and would be remembered as an anthem of the Greatest Generation. Miller composed the music in 1935 as simply “Miller’s Tune.” It went from one publisher to another and eventually to the lyricist Mitchell Parish, who renamed it “Wind in the Trees.” By the time the Glenn Miller Orchestra recorded the song in 1939 as the B side of a 78 rpm on the RCA Bluebird label, a producer had changed the name again, this time to echo the record’s A side, the Frankie Carle composition “Sunrise Serenade.” But while “Sunrise” got a lot of play for several weeks, “Moonlight Serenade” outshone it by far, spending months near the top of the charts and helping Miller’s band (which enjoyed seven No. 1 hits that year) achieve pre-eminence.

Not bad for a trombone player from the Iowa farm community of Clarinda who dropped out of college to play jazz. After working with a few outfits, including the Dorsey Brothers and Ray Noble, Miller launched his first namesake band in 1937. His goal, he once said, was to “create the best all-around band, able to play jazz and ballads with equal skill and good taste.” Following a breakthrough summer in New Rochelle, New York, he reached listeners coast to coast on NBC radio before moving in 1940 to CBS, broadcasting live three nights a week. At one point that year, two out of every three records in jukeboxes were his. Meanwhile, “Moonlight Serenade” played on, such a big part of the Miller brand that a 1941 film featuring the orchestra and set in an Idaho ski resort was called Sun Valley Serenade.

In 1942, nine months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Miller enlisted in the Army. By January 1943, Captain Miller was director of bands for the Army Air Forces Training Command, developing bands at bases across the country as well as leading an elite concert orchestra and radio production unit. He also became an Air Forces spokesman, a war bond fund-raiser and a recruiter.

In England, his band would make 300 personal appearances and nearly 200 broadcasts. “We receive such sincere applause” for “Moonlight Serenade,” Miller said, “I am convinced that what we are doing over here is worth far more than all the money I could have ever made as a civilian.”

Miller was only 40 years old that December day he clambered aboard the C-64 Norseman and set out for France. He never arrived, of course, a loss that it is no exaggeration to say shook the United States and its armed forces. Mystery and rumor long surrounded the aircraft’s disappearance. One prominent theory was that RAF Lancaster bombers returning from an aborted mission had accidentally hit his plane with jettisoned bombs over the English Channel.

I found a more plausible answer while researching my 2017 book, Glenn Miller Declassified. Newly released government documents described the Eighth Air Force’s own investigation of the disaster: The plane, which had a history of carburetor icing problems and hydraulic fluid leaks, most likely froze up and experienced engine failure at low altitude over the frigid sea. To this day, explorers seek the mangled debris of the C-64 among the thousands of pieces of World War II aircraft that litter the English Channel. But the wreckage of the plane that carried Miller has never been found.

Seventy five years later, the Glenn Miller Orchestra—still muted and satin-smooth—continues to open and close every appearance with “Moonlight Serenade.”

“Moonlight Serenade” (Mitchell Parrish-Glenn Miller) (Robbins Music), recorded April 4, 1939, in Victor Studio No. 2 on 155 East 24th Street in New York City. Source: Glenn Miller Archives, American Music Research Center, University of Colorado Boulder and courtesy of the Estate of Glenn Miller and Sony Legacy Music)

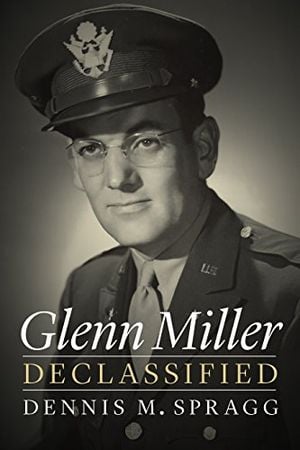

Glenn Miller Declassified

Weaving together cultural and military history, Glenn Miller Declassified tells the story of the musical legend Miller and his military career as commanding officer of the Army Air Force Band during World War II.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.