How the Myth of a Liberal North Erases a Long History of White Violence

Anti-black racism has terrorized African Americans throughout the nation’s history, regardless of where in the country they lived

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3e/ff/3eff5f91-776d-471d-9a6e-a0ffeba18277/philadelphia-abolitionist-fire.jpg)

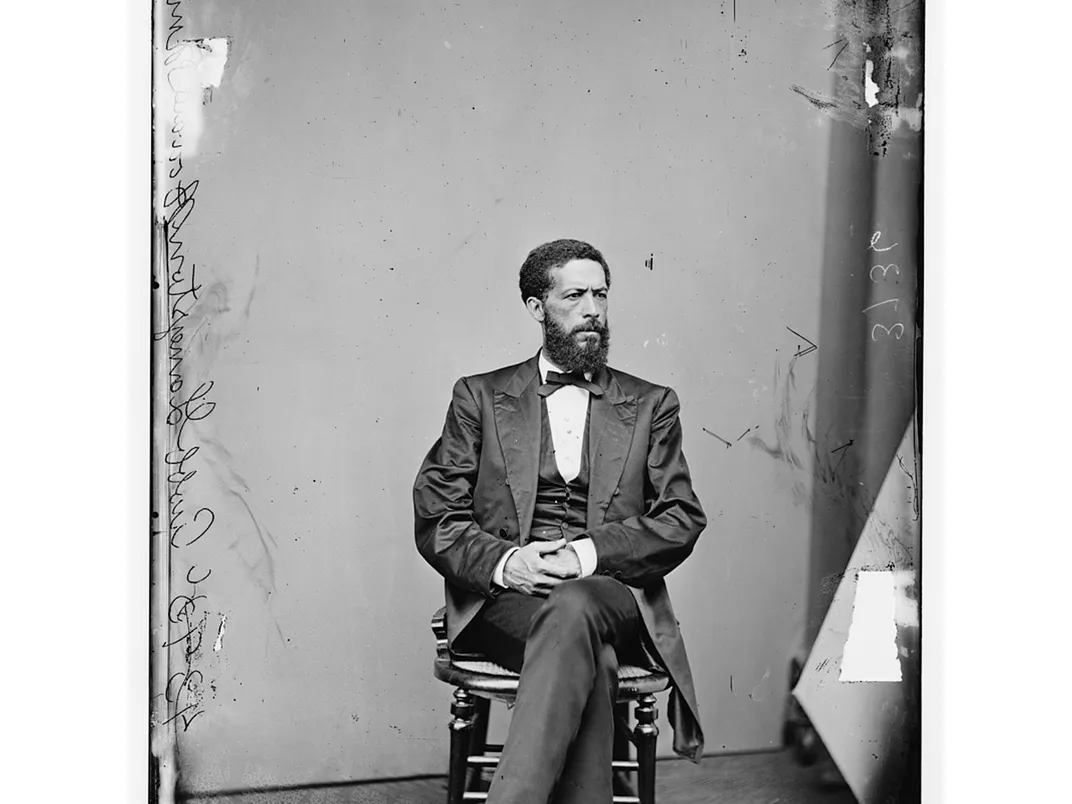

John Langston was running through a neighborhood in ruins. Burned homes and businesses were still smoking, their windows shattered. Langston was only 12 years old, but he was determined to save his brothers’ lives. He had spent the night in a safe house, sheltering from the white mobs that had attacked the city’s African American neighborhood. Sleep must have been difficult that night, especially after a cannon was repeatedly fired. The cannon had been stolen from the federal armory by the white mob, alongside guns and bullets, so they could go to war against Black people.

Langston awoke to worse news. The mayor had ordered all white men in the city to round up any surviving Black men they found and throw them in jail. As John Langston would later write, “swarms of improvised police-officers appeared in every quarter, armed with power and commission to arrest every colored man who could be found.” As soon as Langston had heard this, he ran out the back door of the safe house to find his brothers to try to warn them. When a group of armed white men saw Langston, they shouted at him to stop, but he refused, willing to risk everything to save his brothers.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ca/9a/ca9aa24e-0b2f-4dec-b9d6-d17b6ed75635/tulsa-race-massacre-nmah.jpg)

There is a toxic myth that encourages white people in the North to see themselves as free from racism and erases African Americans from the pre-Civil War North, where they are still being told that they don’t belong. What Langston experienced was not the massacre in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in 1921 or Rosewood, Florida, in 1923—this was Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1841, 20 years before the Civil War broke out. This was the third such racist attack against African Americans in Cincinnati in 12 years.

Cincinnati was not alone. Between 1829 and 1841 white northerners had been rising up against their most successful African American neighbors, burning and destroying churches, businesses, schools, orphanages, meetings halls, farms, and entire communities. These were highly organized actions instigated by some of the most wealthy and most educated white citizens in the North. As a white gentleman in the pretty rural village of Canterbury, Connecticut, wrote in 1833, “the colored people can never rise from their menial condition in our country; they ought not to be permitted to rise here.” He wrote this after white members of his community tried to burn down an elite private academy for African American girls, while the students slept inside.

One of the girls who survived that fire then made the long journey to Canaan, New Hampshire, where a few abolitionists were trying to establish an integrated school called the Noyes Academy. Canaan was a remote and lovely village but within months, white locals attacked that school. The white attackers brought in numerous teams of oxen attached to a chain they put around the school, and pulled it off its foundation, dragging it down the main street of Canaan.

In 1834 there were even more riots against African Americans, most notably in New Haven, Connecticut, Philadelphia, and New York City. The mayor of New York allowed the destruction of African American homes and businesses to continue for days before finally calling out the state militia. This violence was not against buildings alone, but was accompanied by atrocities against African Americans, including rape and castration.

African Americans in the North bravely continued to call for equality and the ending of slavery, while the highest officials in the land tried to encourage more massacres. As Lacy Ford revealed in his book Deliver Us from Evil, President Andrew Jackson’s secretary of state, John Forsyth, wrote a letter asking Vice President Martin Van Buren—born and raised a New Yorker—to organize “a little more mob discipline,” adding, “the sooner you set the imps to work the better.” The violence continued; historian Leonard Richards makes a conservative estimate of at least 46 “mobbings” in Northern cities between 1834 and 1837.

White leaders in Cincinnati gathered in speaking halls to encourage another attack against African Americans in that city in 1836. Ohio Congressman Robert Lytle helped to lead one of these rallies. As Leonard Richards noted in his book Gentlemen of Property and Standing, the words he thundered to his audience were so vile that even the local newspapers tried to clean them up, changing words and blanking them out, printing a quote that read that the Colonel urged the crowd to “castrate the men and ____ the women!” But the white people in the crowd did not hear this sanitized version; they heard a demand for atrocities, and soon there was another attack against African Americans in that city. Two years later Lytle was made Major General of the Ohio Militia.

In 1838 Philadelphia again saw white people organize to destroy Black schools, churches, meeting halls, and printing presses, and then finally Pennsylvania Hall. Over 10,000 white people gathered to destroy the hall, one of the grandest in the city. Pennsylvania Hall was newly built in 1838 with public funds and was meant to be a national center for abolitionism and equal rights. Its upper floor had a beautiful auditorium that could seat 3,000 people. It had taken years of fund-raising by African Americans and sympathetic white people for the hall to be built, but it took just one night for it to be destroyed. This destruction was quickly followed by violence by white Pennsylvania politicians who rewrote the state’s constitution, excluding free African Americans from the right to vote. An overwhelming majority of white men in Pennsylvania enthusiastically voted for the new Constitution.

This physical destruction of African American neighborhoods followed by the stealing of African Americans’ rights was a double-edged violence, and it was not unique to Pennsylvania. Back in 1833 in Canterbury, Connecticut, the girls managed to escape their school when it was set on fire, but soon all African Americans in Connecticut were made to suffer. White lawyers and politicians in Connecticut saw to that. A lawsuit brought against Prudence Crandall, director of the school, resulted in the highest court in Connecticut deciding that people of color, enslaved or free, were not citizens of the United States. White people could now pass any racist laws they pleased, including one making it illegal for any person of African descent to enter the state of Connecticut to be educated there.

While the 1830s saw an intense period of this violence, white northerners had a long history of attempting to control the actions of Black people; they had been doing so since the colonial period when race-based slavery laws made all non-whites subjects of suspicion. In 1703 the Rhode Island General Assembly not only recognized race-based slavery, but criminalized all Black people and American Indians when they wrote:

If any negroes or Indians either freemen, servants, or slaves, do walk in the street of the town of Newport, or any other town in this Collony, after nine of the clock of the night, without a certificate from their masters, or some English person of said family with them, or some lawfull excuse for the same, that it shall be lawfull for any person to take them up and deliver them to a Constable.

Northern slavery began to fall apart during the American Revolution, but the dissolution of race-based bondage was a long and protracted process and Black people were held in bondage in northern states well into the 1840s. Most northern states enacted Gradual Emancipation Laws to legally dismantle slaveholding; however, it was actions of Black people themselves—freedom suits, writing and publishing abolitionist pamphlets, petitioning, self-purchase, military service, flight and revolting—that made this a reality. There was also a brief move towards equal rights. By 1792 the entire Northwest Territory (Ohio, Illinois, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Indiana, and Michigan) as well as 10 of the 15 states had opened up the vote to all men regardless of the color of their skin. But white northerners, native- and foreign-born, resented the increasing free and growing Black population. And when African Americans dared to live like free people they were violently attacked.

In 1824 and 1831 white mobs attacked African American enclaves in Providence, Rhode Island, when Black people refused to show public deference to white people. On October 18, 1824, a group of Black residents of the Hardscrabble neighborhood refused to step off the sidewalk when a group of whites approached. Their insistence on their right to the sidewalk met an onslaught of violence. Dozens of angry whites destroyed nearly all the Black-owned homes and businesses in Hardscrabble. No one was punished and the Black residents received no compensation for the loss of their property. Seven years later, when a Black man stood on his porch with his gun, refusing to allow a group of white men to attack his home and family, the violence in Providence became the deadliest the city had ever seen. The white mob ravaged the Snow Town neighborhood for four days until the governor finally decided that enough damage had been done and called in the state militia to quell the rioters. Again, no one was punished, and Black residents were not compensated. Instead they were blamed for provoking the riot with their assertions of independence.

Black freedom, rising and slowly increasing equal rights was what threatened most white northerners, because black emancipation meant that whiteness in and of itself was no longer a clear marker of freedom if Black people were also free. By the middle of the 1800s, there was a backlash against the growing free Black population in the North. They no longer had the full protection of the law, had the right to vote stolen from them, and could not sit on juries and serve in the militia. Northerners also segregated schools, public transportation, and accommodations. White people in nearly every northern state before the Civil War adopted measures to prohibit or restrict equal rights and the further migration of Black people into their jurisdictions—especially the new northern territories and states of Ohio, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Iowa, Wisconsin, California, and Oregon. And all of this occurred before the Civil War and the end of slavery.

The persistent myth of a post-Revolutionary North embracing African Americans and protecting their rights has been deliberate. Historians have long written about African-descended people, enslaved and free in the North before the Civil War. It is no secret that white northerners responded to this population with cruelty and violence. Leonard Richards published his book on some of these events in 1970 and David Grimsted published his book on mob violence before the Civil War in 1998. Yet the majority of white historians have focused on the ways in which these mobs attacked white abolitionists, even though Black lives were at the root of this violence. And it was Black people who suffered the most from it.

That suffering continues to be buried. For example, many historians note the 1837 murder of white abolitionist Elijah Lovejoy in Illinois. The mob attacking Lovejoy and his abolitionist press made it clear that they were not just angry about his views and publishing, they were motivated by racism. As a white farmer in the mob yelled out, “How would you like a damned n***** going home with your daughter?” But no academic historian has investigated what happened to the African Americans in Alton, Illinois, and the surrounding countryside, some of whom had been farming their own land since the early 1820s. This lack of interest and attention to this racist violence is deliberate. As Joanne Pope Melish made clear in 1998, in her book, Disowning Slavery, if you create a myth of an all-white North before the Civil War, it becomes much easier to ignore a history of violence against Black people there.

However, African Americans have long known that they have deep roots in all regions of the United States. As the African American Bishop Richard Allen wrote in 1829, affirming that Black people belonged:

See the thousands of foreigners emigrating to America every year: and if there be ground sufficient for them to cultivate, and bread for them to eat, why would they wish to send the first tillers of the land away? . . . This land which we have watered with our tears and our blood, is now our mother country.

Christy Clark-Pujara is Associate Professor of History in the Department of Afro-American Studies at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. She is the author of Dark Work: The Business of Slavery in Rhode Island. Her current book project, Black on the Midwestern Frontier: From Slavery to Suffrage in the Wisconsin Territory, 1725 to 1868, examines how the practice of race-based slavery, black settlement, and debates over abolition and Black rights shaped White-Black race relations in the Midwest.

Anna-Lisa Cox is an historian of racism in 19th-century America. She is currently a Non-Resident Fellow at Harvard’s Hutchins Center for African and African American Research. She was a Research Associate at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, where her original research underpinned two exhibits. Her recent book The Bone and Sinew of the Land: America’s Forgotten Black Pioneers and the Struggle for Equality was honored by the Smithsonian Magazine as one of the best history books of 2018. She is at work on two new book projects, including one on the African Americans who surrounded and influenced the young Abraham Lincoln.