How Neil, Buzz and Mike Got Their Workouts in on Their Way to the Moon and Back

To counter the effects of weightlessness, NASA equipped Apollo 11 with an Exer-Genie for isometric exercises

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5e/79/5e79036c-5605-4122-aa09-41ceb3198cd2/candid_apollo.jpeg)

Concerned about the effects of weightlessness on space travelers, NASA encouraged the Apollo 11 astronauts to exercise multiple times each day in flight. However, when the mission was over, Neil Armstrong, the first human being to make footprints on the dust-peppered lunar landscape, reported: “We all did a little bit of exercise almost every day.”

According to fellow astronaut John Glenn, the first man on the moon was not a strong believer in exercise regimens. In his memoir, Glenn, who was an avid runner, reported that Armstrong had a theory about exercise that would make any couch potato proud. “Everyone was allotted only so many heartbeats,” said Armstrong, “and he didn’t want to waste any of his doing something silly like running down the road.” No matter his beliefs, as a former naval aviator, Armstrong, no doubt, got his share of exercise before he walked on the Moon.

In a post-flight Apollo 11 debriefing on their exercise routines, Buzz Aldrin argued that “you are not going to deteriorate that appreciably in three days [to get to the moon and three days to get back],” and Michael Collins added, “I had the idea that it was worth exercising on the way home and maybe not worth exercising on the way out.” Apparently, work to accomplish a successful mission combined with the whirlwind of anticipation to make exercise a low priority during the nine-day mission.

“There wasn’t a full understanding back then of just how necessary exercise is to maintaining body composition, especially muscle tone,” says Jennifer Levasseur, a curator at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. “We were just in the very beginning stages of understanding that.”

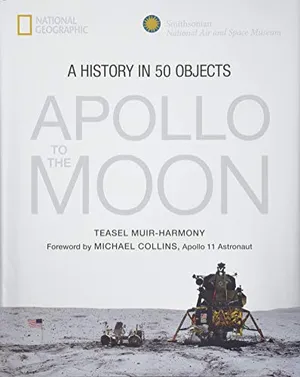

Apollo to the Moon: A History in 50 Objects

This book showcases the historic space exploration program that landed humans on the moon, advanced the world's capabilities for space travel, and revolutionized our sense of humanity's place in the universe. Each historic accomplishment is symbolized by a different object, from a Russian stamp honoring Yuri Gagarin and plastic astronaut action figures to the Apollo 11 command module, piloted by Michael Collins as Armstrong and Aldrin made the first moonwalk, together with the monumental art inspired by these moon missions.

Sometimes, Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins did calisthenics, but they also used a contraption called the Exer-Genie. This isometric gizmo offered a wide variety of ways to build strength. The off-the-shelf exercise equipment had traveled on Gemini missions before NASA made changes to improve its usefulness on Apollo missions. As a guideline, NASA told Apollo astronauts to exercise several times each day for 15 to 30 minutes, writes the museum’s curator of space history Teasel Muir-Harmony in her new book, Apollo to the Moon: A History in 50 Objects.

The Apollo 11 Exer-Genie is now part of the National Air and Space Museum’s artifact display marking the 50th anniversary of the history-making flight.

The compact Exer-Genie fit into the space agency’s thinking about the efficiency of equipment used in space travel, says Levasseur: NASA employees “were always looking for ways to consolidate all of the needs into a single object, to be able to minimize the amount of space and weight that those things would take up.” The gadget fit easily in a storage locker, given its length of 49 5/8 inches and width of only 1 ¾ inches. “Made up of an aluminum cylinder wrapped with nylon rope inside a metal tube, the exercise machine provided astronauts with adjustable conditioning levels to perform up to a hundred different exercises in space,” according to Muir-Harmony. Among the options were a horizontal press, sit-up, side bend, biceps curl and hamstring stretch. To set up the machinery in the cramped spacecraft, “they attached the two top straps to the wall of the command module, set the resistance, and used the bottom straps, pulling and stretching at various angles and positions.” Armstrong reported that it “worked alright,” but when used vigorously, the handle literally became too hot to handle, Collins said.

During its use on several other Apollo missions, the multipurpose mechanism drew differing reactions. The crew of Apollo 7 discovered in October 1968 that the Exer-Genie helped to relieve back pain from sleeping in tight spaces, Muir-Harmony reports; however, in April 1972, Apollo 16 command module pilot Ken Mattingly thought the crew’s time could be spent more effectively on other tasks.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/78/b5/78b51f7d-c6fc-4785-b0c0-faea43173ce9/624241main_1969-07-16-1_full.jpg)

One problem for the astronauts, Levasseur notes, was that “they needed to have adequate footholds” to establish the necessary stability to make their muscles work effectively with the equipment. Aboard a craft in which every ounce of weight must be measured against the necessity of lifting the vehicle into space, free surfaces for planting one’s feet were not easy to find. The spacecraft had not been designed with this requirement on the agenda. That made use of the Exer-Genie more challenging.

Introduced in 1961, the Exer-Genie offered would-be athletes and fitness fans a compact, easy-to-use alternative to lifting weights or performing calisthenics. The product’s big break came in August 1968, almost a year before Apollo 11’s mission, when it was featured in a Sports Illustrated article that labeled it as a “seemingly innocuous little device.” The article praised the compact exerciser: “Though Exer-Genie itself weighs only 1.5 pounds and easily fits into a briefcase, it now plays a major role in the training programs of a number of first-rate college swimming teams, professional football and baseball teams, not to mention a growing number of non-athletes who simply desire a good, quick workout in their own homes.”

Making the decision to purchase and use this product is “an example of one of these instances where NASA leveraged developments in the corporate world to enable astronauts to do their job,” Levasseur says. NASA had experimented with its own exercise ideas. Rita Rapp, who would become responsible for the Apollo astronauts’ food, earlier designed Gemini astronaut exercises that involved using elastic equipment during flight to challenge muscles—not vastly different from the idea behind the Exer-Genie. Later, after discovering a ready-made product that accomplished its needs for challenging exercises without minimal storage requirements, NASA decided to adopt it. The device, now with padded handles, remains on sale today, and its manufacturer proudly draws attention to its use in the space program on its website.

Today, the effects of weightlessness continue to be a significant concern in manned space missions, and this will become an even higher priority as NASA looks ahead to the coming decades with plans for longer missions on the moon and possible voyages to Mars. The space agency recently released the results of a multi-year study that focused on identical twin astronauts Scott and Mark Kelly.

Scott spent nearly a year on the International Space Station from March 2015 to March 2016, while his brother, then a retired astronaut, remained on Planet Earth. Before, during, and after his flight, simultaneous medical testing of both brothers measured their physical conditions. Follow-up testing traced how time on Earth after Scott’s flight affected changes from in-flight findings. Scott’s chromosomes, his retina and his carotid artery showed unexpected changes, but most returned to normal after several months back on Earth. The chromosome changes, in particular, surprised scientists. The ends of Scott’s chromosomes, their telomeres, increased in length during the flight but returned to a more normal length after his space station mission. Since telomeres become shorter as we age, scientists are not sure how to interpret these changes. Scott also received flu shots before the flight, during the flight and after its completion. Results showed that his immune system responded normally. This marked the first time an astronaut had ever been vaccinated in space.

Scott Kelly’s experience in space differed greatly from those of Apollo astronauts. Moon-bound spacecraft offered astronauts an extremely confined space with little available room for exercise. Astronauts on the comparatively spacious space station have multiple options to strengthen their muscles: They include an exercise bike, a treadmill and a weight machine. In fact, Scott Kelly’s body mass decreased 7 percent in flight, partly because he exercised more during his 340-day mission on the space station than he routinely worked out on Earth. Though not a big issue on the space station, the availability of room to exercise may again become a challenge in future long-distance or extended-duration assignments. While identical twins offered researchers a rare opportunity, scientists were quick to point out that many more tests lie ahead before the effects of space travel are fully understood.

“NASA believes that our goal is to stay in space long-term to have a permanent human presence in space, and to do that, we have to be able to prepare the human body for it. Early experiments with exercise have really gone on to inform all of the equipment that has come after it,” says Levasseur. “There’s even more of a concern going forward with exploration about how to sustain the human body’s muscle mass, skeletal structure and stability.”

The Apollo inflight exerciser is currently on view at the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)