How One Mummy Came to the Smithsonian

An American diplomat’s memento takes center stage after 125 years

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Object-at-Hand-Egyptian-Mummy-631.jpg)

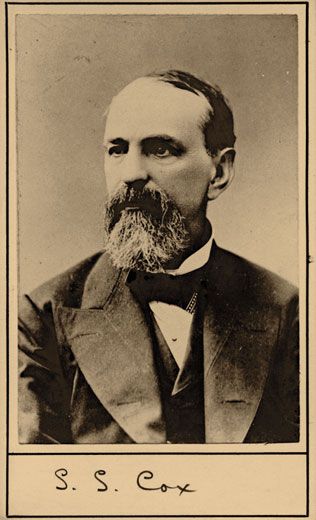

During a holiday in Egypt, former New York congressman Samuel Sullivan Cox, appointed in the mid-1880s by President Grover Cleveland as U.S. envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary to Turkey, had a distinctive take on collecting souvenirs. The mementos Cox acquired in the land of the Nile, he later wrote, were “two emigrants which I sent from Egypt, one of whom has now an isolated residence in the National Museum.”

The museum would one day be known as the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History (NMNH). His Egyptian keepsakes were, in fact, mummies. But Cox—a lawyer, journalist and author who served 16 terms as a member of Congress for Ohio and, later, New York—was no pillager of pyramids. The ancient specimens were presented to him as a ceremonial gift from the Ottoman Empire’s viceroy, or khedive, in Egypt. (The other mummy went to the George West Museum in Round Lake, New York.)

Today, the Smithsonian mummy takes pride of place, along with three fellow mummies from NMNH collections, at the museum’s exhibition “Eternal Life in Ancient Egypt.” The show’s more than 100 artifacts survey ancient Egyptian burial practices and cosmology. According to Melinda Zeder, curator of Old World archaeology, the Cox mummy is “our best preserved and most richly decorated [specimen]. Though he clearly wasn’t a nobleman, he was very likely a wealthy person.”

Mummies, by virtue of their venerable age, are exquisitely fragile; their mysteries are best plumbed by high-tech investigation. X-ray and CT scans by Smithsonian scientists indicate that he was 5-foot-6 and about 40 years old when he died two millennia ago. At the time that Cox’s Egyptian relic entered the museum collections, curators described the acquisition as “delicately proportioned, and ...altogether a very good specimen.”

The techniques of mummification—an ancient practice of desiccation far different from modern embalming—were carried out by a flourishing professional trade and came to an end in Egypt only as Christianity rose to dominance. The purpose was to keep the bodies of the dead intact for what ancient Egyptians believed was a full, corporeal eternal life. “Unlike what people sometimes think,” says Zeder, “the Egyptians were not obsessed with death, but with life.”

The process was elaborate. The drying that prevented decay of the body was accomplished using natron, a mix of four salts found in abundance along the Nile. Mummy makers also used palm wine as a disinfectant and frankincense as a perfume.

Although today Egyptian mummies are, of course, protected by laws governing national patrimony, in the 19th and early 20th centuries they were fair game for archaeologists, travelers and looters. For centuries, then, a large number of Egyptians have been spending their afterlives far from the Nile.

The Cox mummy’s journey to the Smithsonian began in Luxor, across the Nile from the Valley of the Kings, a place of powerful symbolic importance where pharaohs such as Tutankhamen were entombed. Clearly, the viceroy who wished to bestow these gifts to the American was someone who did his homework. According to S. J. Wolfe, author of the 2009 Mummies in Nineteenth Century America: Ancient Egyptians as Artifacts, the khedive had read Why We Laugh, a book by Cox, a polymath who produced tomes on subjects from the Greek islands to England’s Corn Laws. The 25-chapter treatise on humor is regrettably short on laughs. The khedive, no doubt with more than a touch of irony, informed Cox: “I enjoyed your book exceedingly. And now I propose to present you with something as dry as your book, I will give you two mummies.”

Lana Troy, an American professor of Egyptology at Uppsala University in Sweden, who helped to organize the NMNH exhibition, told me it was “relatively common for dignitaries visiting Egypt in the 19th century to acquire mummies and ancient artifacts as gifts.” However, the fact that the mummy was presented to Cox in Luxor, says Troy, doesn’t mean it had been found there. “It is doubtful we will ever know more about the mummy’s origin than what the few records tell us,” she says. “He was from the late period of mummification [roughly 100 B.C. to A.D. 200].” All in all, Troy adds, “He’s a good mummy for the time he comes from—a time of quick, budget-priced mummies—and a wonderful exhibition piece.”

Owen Edwards is a freelance writer and the author of the book Elegant Solutions.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)