How Portraiture Gave Rise to the Glamour of Guns

American portraiture with its visual allure and pictorial storytelling made gun ownership desirable

:focal(1238x447:1239x448)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/39/9f/399f478f-4001-450f-9f57-19618a870a70/saam-1981142_1.jpg)

The Men of Progress, an 1862 painting by Christian Schussele, held in the collections of the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery, features 19 of the era’s prominent inventors, gathered together before a large portrait of Benjamin Franklin—the father of American ingenuity. The gentlemen seem engaged in earnest conversation around a table where Samuel Morse is demonstrating his telegraph machine. But one man looks directly at the viewer—Samuel Colt, his gun is at the ready on the table beside him.

Colt was the inventor of the 1836 revolver mechanism that made it possible to fire multiple times before reloading, and his inclusion in this pantheon of 19th-century American ingenuity says much about his significance—elevated to the status of such luminaries as Charles Goodyear, who brought forth vulcanized rubber, Cyrus McCormick, who invented the mechanical reaper and Elias Howe, who created the sewing machine.

In many respects, Samuel Colt's pointedly direct gaze as a “man of progress,” and portraiture in general from the 1840s onwards, helped to accelerate gun ownership through the United States. With its visual allure and pictorial storytelling, art and celebrity, portraiture made gun ownership desirable at a time when government capital, patent protection, technological improvement and mass production made them cheaper.*

Even before the American Revolution, the U.S. government had searched for a reliable domestic manufacturer to supply weapons to its army and volunteer militia. While fighting the British, General George Washington regularly complained about the lack of reliable weaponry. General Winfield Scott discovered much to his dismay that he was expected to engage Native Americans on the Western frontier largely without firepower. During Nat Turner's 1831 rebellion, newspapers reported that the local police were "very deficient in proper arms," to defend themselves, and nearly every officer's report on both the Union and Confederate side during the Civil War detailed the shortage and poor quality of their guns.

A scene in the 2012 Steven Spielberg film Lincoln marvelously depicts the inadequacy of the technology when a congressman attempts to shoot anti-slavery lobbyist William Bilbo, but while the congressman reloads, Bilbo has plenty of time to run away.

Following the Civil War, portraiture helped to glamorize that transition by illustrating tough guys and girls who bore arms with self-confidence and swagger.

Setting aside military images, where the inclusion of guns is both necessary and inevitable; portraits of American citizens with guns fall into three symbolic "types": the gun as a symbol of bravery; the gun as symbol of defense of land; and the gun as ornament or theatrical prop. Advances in photographic reproduction and cinematography especially at the turn of the 20th century eventually saw the gun used as an artistic device that connected the imaginary world of entertainment to that of the viewer in the real world.

The notion of "gun vision" put forth by art historian Alan Braddock in his 2006 article "Shooting the Beholder," suggests that portrait artists underplayed and deemphasized the implied violence of a pointed gun as a way to address a growing public desire for attention and spectacle.

The gun as a symbol-of-bravery makes its appearance in the mid-19th century in portraits of Native Americans and African-Americans, primarily reserved for those who resisted capture, slavery or relocation. Significantly in these pictures, the rifle is highly symbolic and placed at a distance to the figure; stock-end down on the ground and pointed towards the sky at little risk of being fired.

In 1837, artist Charles Bird King painted a full-length portrait of the Chippewa chief, Okee-Makee-Quid, holding a ceremonial pipestem vertically alongside his body. One year later, George Catlin’s portrait of Osceola depicts the Seminole warrior standing with the rifle he used to kill the U.S. Indian Agent Wiley Thompson in defense of tribal lands. Tricked into capture under the pretense of negotiating a truce, Osceola eventually died in captivity, but not before Catlin visited him in prison to create a portrait intended to honor his bravery that showed the Indian holding a rifle—in place of his peace pipe—parallel to his body “as the master spirit and leader of the tribe.”

Between 1836 and 1844, a three-volume portfolio of portraits published by Thomas McKenney and James Hall on The History of the Indian Tribes of North America, set the template for the display of Native chiefs most notably focused on their bright dress and beaded and feathered adornments that appeared so exotic to Euro-American audiences. Many of the subjects are shown holding ceremonial pipestems and wearing peace-medals used by the government in a diplomatic exchange for compliance with Westward Expansion policies. Engraved on a 1793 silver medal depicting George Washington, the exchange-of-guns-for-amity is vividly displayed as the general holds in one hand his rifle by his side and with the other hand, joins the Native American in smoking a peace pipe, standing in the fields of a newly settled farm.

Early portraits of African-Americans have been rendered similarly pacifist. An 1868 wood engraving of Harriet Tubman by John Darby shows Tubman dressed as a scout for the Union Army holding a large rifle with her hands curiously placed over the barrel of the gun. A similar hand-over-the-gun-barrel stance resurfaces in a portrait of cowboy Nat Love around a decade later; as if to indicate that if the weapon was to fire, it would harm him first. Similarly, in an 1872 advertisement for Red Cloud chewing tobacco, the figure’s hand is also placed over the gun barrel.

At the same time, guns are used to illustrate the idea of defense of land, hunting literature begins to describe a more intimate relationship with being "armed." Loving descriptions of guns as "well-oiled," "sleek" and "gleaming;" and being "cradled," "caressed" and "hugged" by their owners proliferates. In The American Farm Hand of 1937 by Sandor Klein, a farmer seated in a cane chair looks directly at the viewer and clutches a shotgun halfway down the barrel. The rifle is closest to the viewer and the polished wood handle and steel barrel sensuously echo the sinewy arms and bare torso of its owner.

Looking directly at the viewer with farm buildings in the background below a darkening sky, the farmer signals that he is prepared to protect his lands and property, which includes a black field worker pitching wheat in the middle ground.

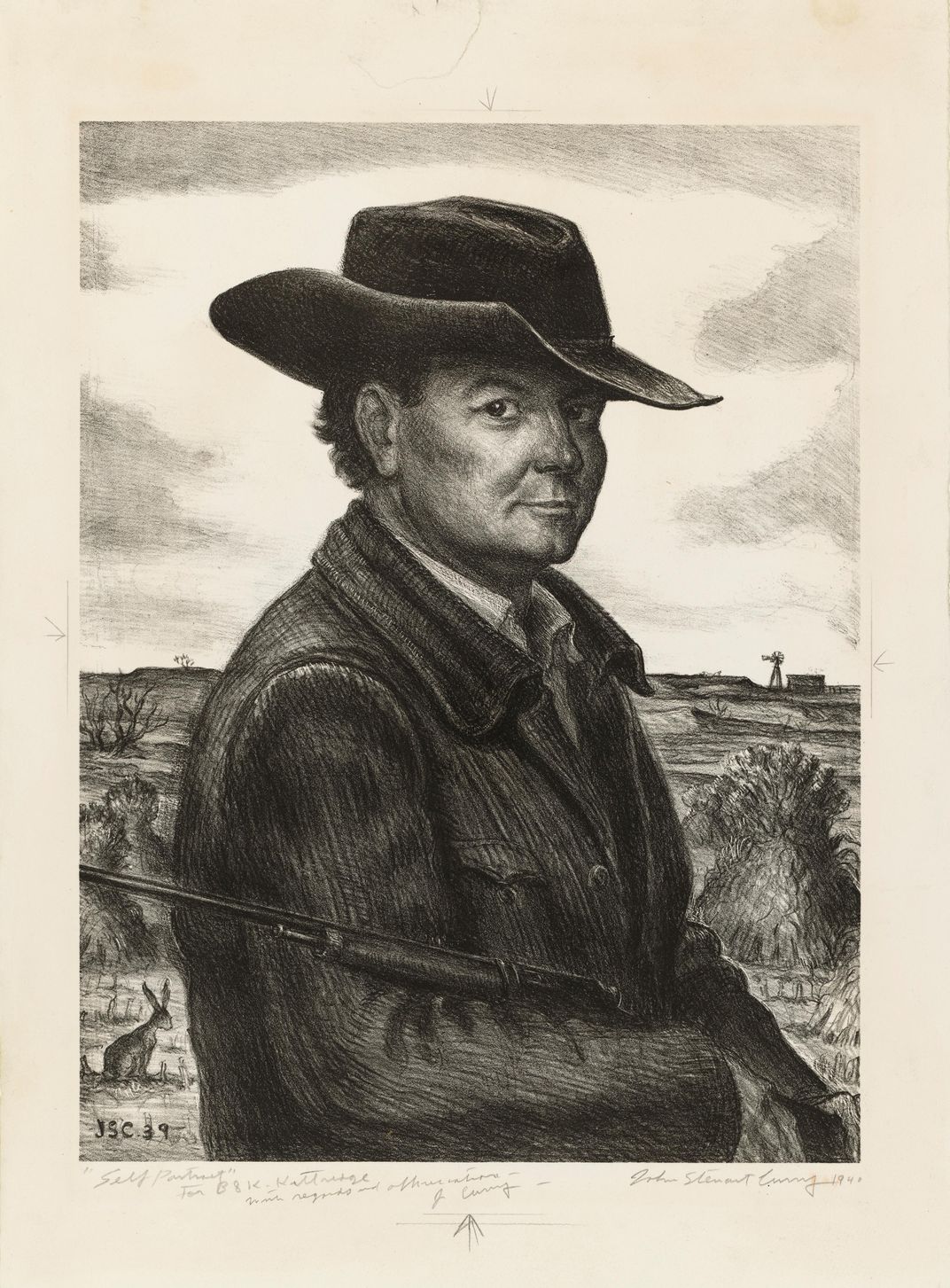

In John Steuart Curry's Self-Portrait of 1939, the artist similarly looks directly at the viewer, but the gun is more companionably cradled in the crook of his arm. Harvested wheat and the faint outline of a farm are shown in the background, and, like Klein's painting, there is a self-assuredness as the sitter holds his weapon close.

Linking the harvest and farming with armed defense became a pictorial leitmotif especially prevalent during World War II. In a painting by Curry dating to 1942 entitled The Farm is a Battlefield, a farmer carrying his pitchfork marches alongside soldiers pointing rifles. Both farmer and soldier carry weapons to protect land and nation. Similarly, in a mural design created by Charles Pollock, a soldier stands between the wartime chaos of bombed aircraft, fire and smoke, an engineer working gears, and a farmer standing in a field of wheat.

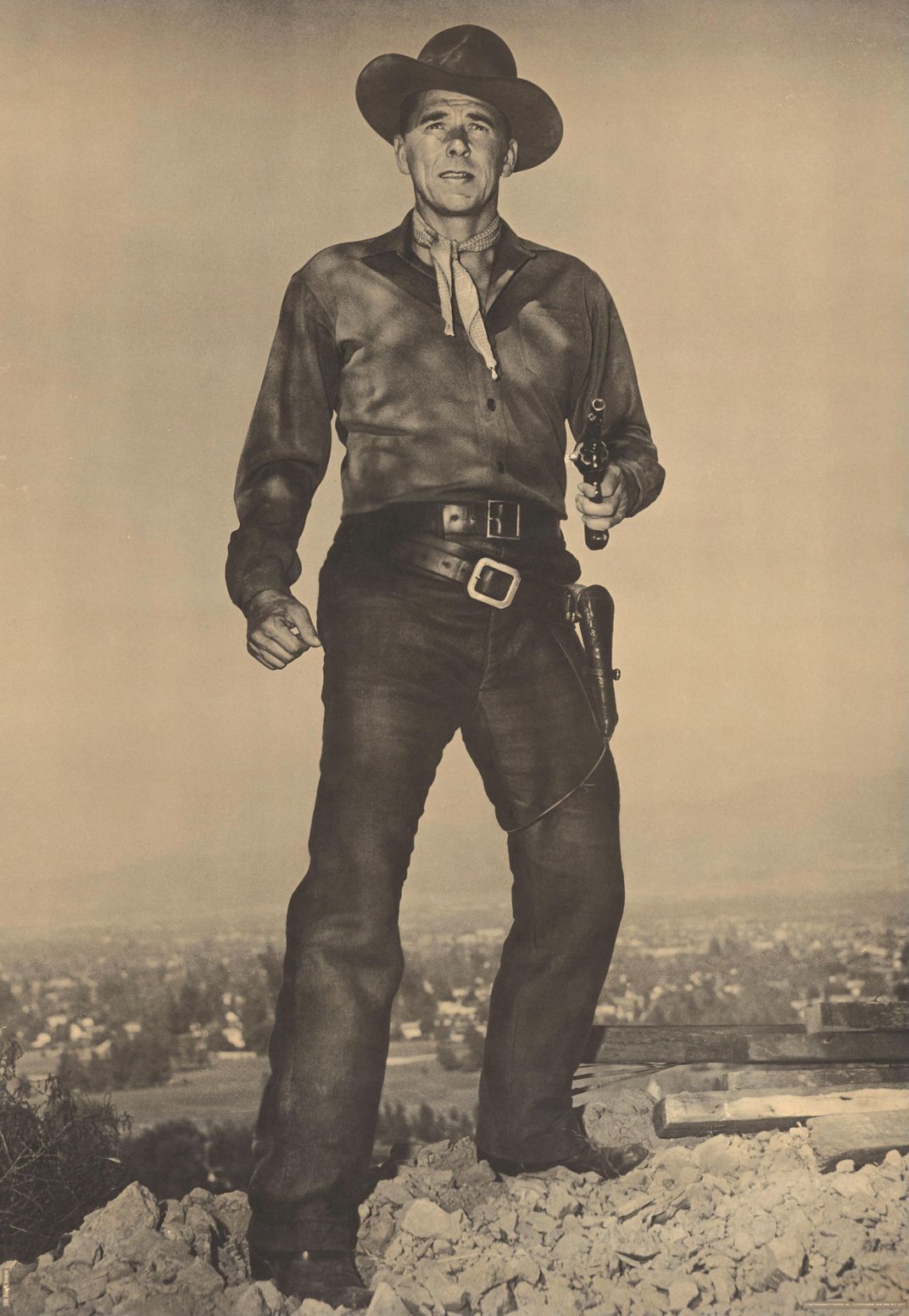

Following World War II, heroic depictions of bare-chested men spread with the rise of photography and Hollywood publicity stills that promoted Western film stars like Robert Ryan, Ty Hardin, Clint Walker, Steve McQueen and Paul Newman. Cowboy actors are shown holding their guns next to bare skin as an extension of their bodies. In a particularly telling publicity still for the 1951 film Giant, an open-shirted James Dean—who played Jett Rink, a Texas ranch hand who strikes it rich—holds a rifle across his shoulders as he looks down on the actress Elizabeth Taylor kneeling before him.

Naturally, to be bare-chested was not terribly practicable for a working cowboy, and the paraphernalia associated with carrying guns, such as bandoliers and holsters draped over denim shirts, leather vests and chaps to protect legs from shotgun shrapnel also became part of the man-as-protector persona as demonstrated by John Wayne.

The third type of gun portraiture—as ornament or theatrical prop—corresponds with the rise of photography and celebrity in the late 19th century, thanks to the growing public relations industry that circulated portraits of the famous and soon-to-be-famous stars via the popular yellow press, dime novels and magazines.

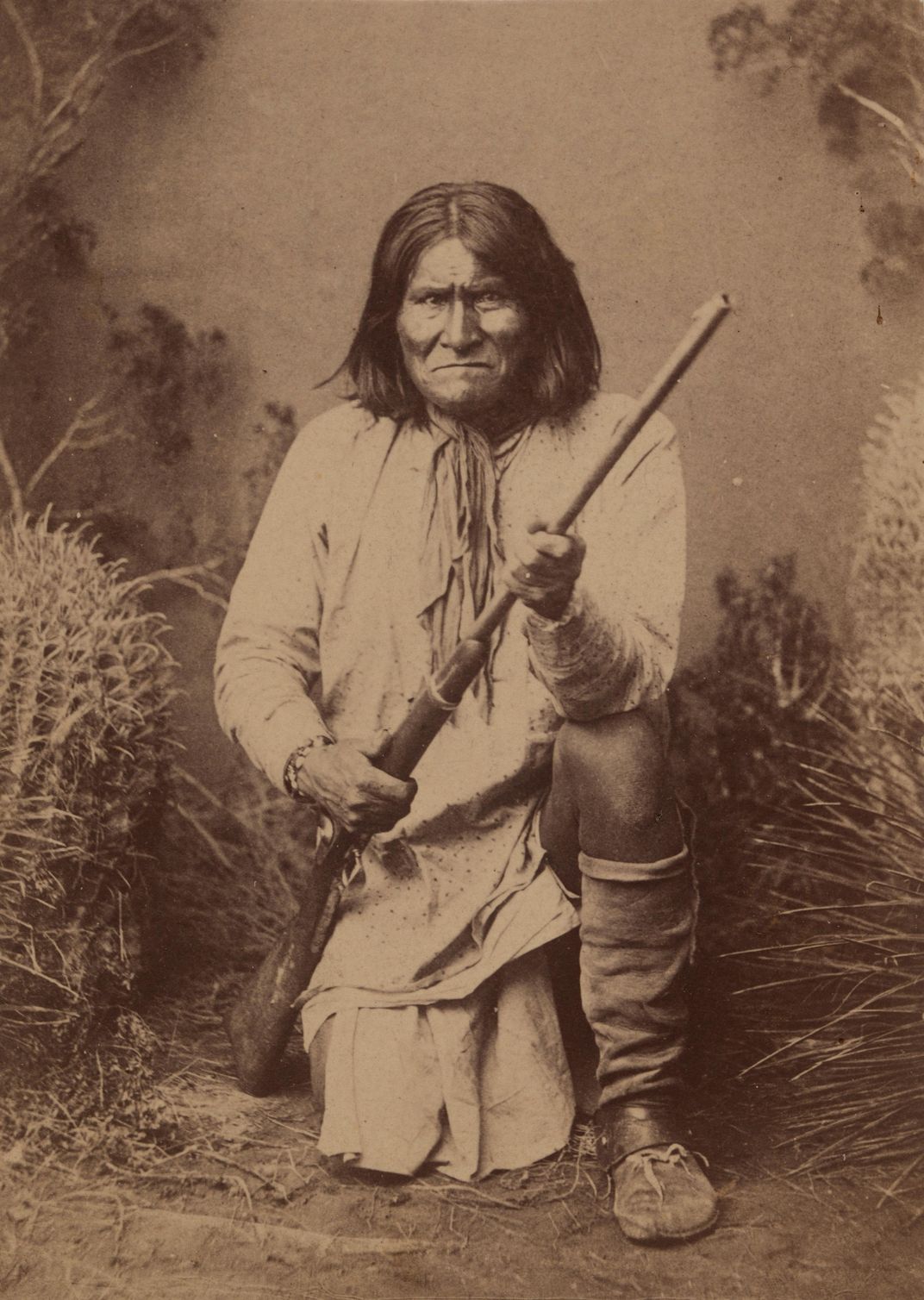

One of the earliest in this genre is the Apache warrior Geronimo by the itinerant photographer A.F. Randall, who met the famed fighter in the year of his capture and posed him kneeling in a faux landscape pointing his rifle. Randall was one of the many artists to make a name for themselves by capturing on film the man salaciously described as "easily the wickedest Indian alive today." Similarly, H. R. Lock documented Martha Cannary, otherwise known as Calamity Jane, around 1895 in his studio holding her rifle in front of a painted backdrop. At age 25, the girl gunslinger had gained a national profile when she was featured as a sidekick to the character of Deadwood Dick in the first of several dime novels.

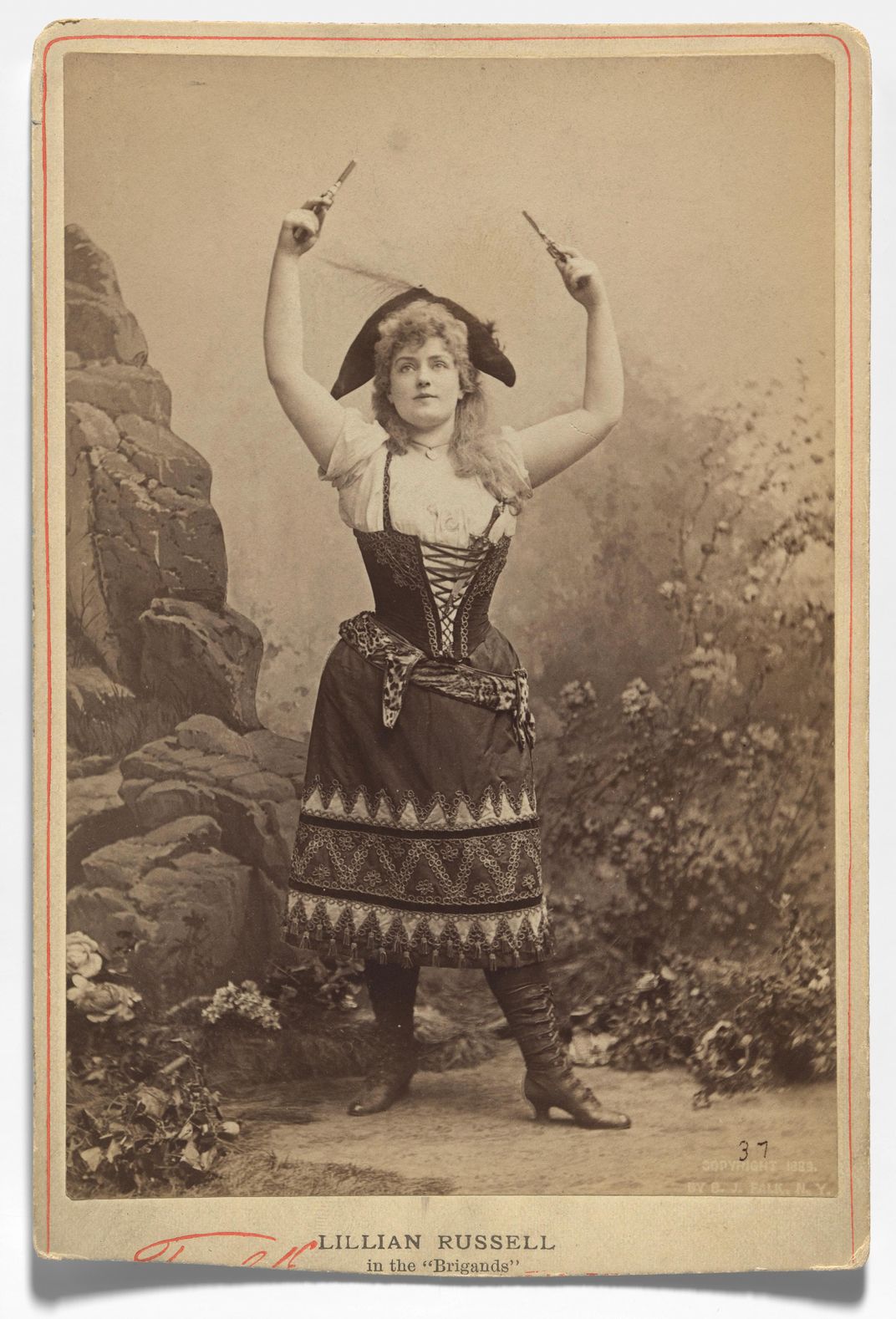

The leap from real people to actors brandishing guns for theatrical effect was both quick and widespread as photographic technologies improved. From 1855 until the late 1900s portable cabinet cards became immensely popular collectibles. Portrait photographers went to elaborate lengths to stage celebrities for dramatic effect in faux interiors. When dramatizing an actor’s role in a Western, or less frequently in a historical battle scene, the potential violence was watered-down. Putting a gun in the hands of women and minorities, made their use more socially acceptable as Lillian Russell's portrait of 1889 and Betty Hutton's in 1950 so aptly illustrate.

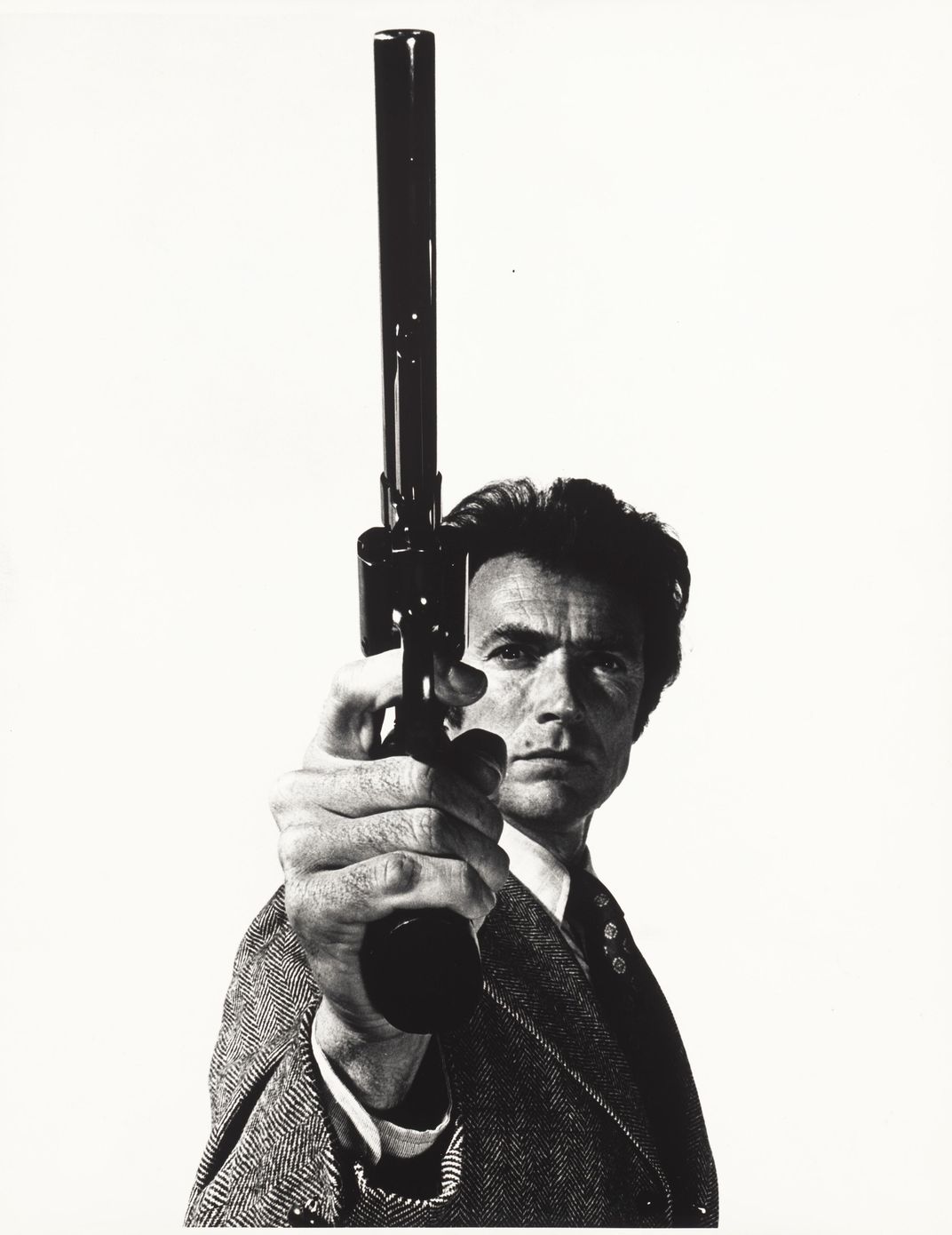

While advances in civil rights also opened doors for women and minority actors to become gun-wielding western heroes, war heroes, detectives, spies, gangsters and vigilantes, it also led to a style of portraiture that simulated shooting the audience. In this form of "gun vision," as defined by art historian Alan Braddock, the weapon points out of the fictive world into the real one and "shoots the beholder." The implied threat of death becomes a visual spectacle; a surrogate real-life moment. We are looking directly at the gun, and it is looking back at us.

By the 1900s the camera's ability to literally freeze a moment in time contributed to the "distinctly modern interplay between art and arms." Adopting the rhetoric of hunting to “load,” “aim” and “shoot,” the photographer is “capturing” a moment in time. A 1909 advertisement for Kodak, for example, suggests the consumer replace looking down a barrel with looking into a lens. Simultaneously, as a 1942 portrait of Paul Muni in the film Commandos Strike at Dawn demonstrates, gun vision also implied that the direct confrontation in the fictive world demanded some action by the viewer in the real one. In this case to defend the home front at the start of the second World War.

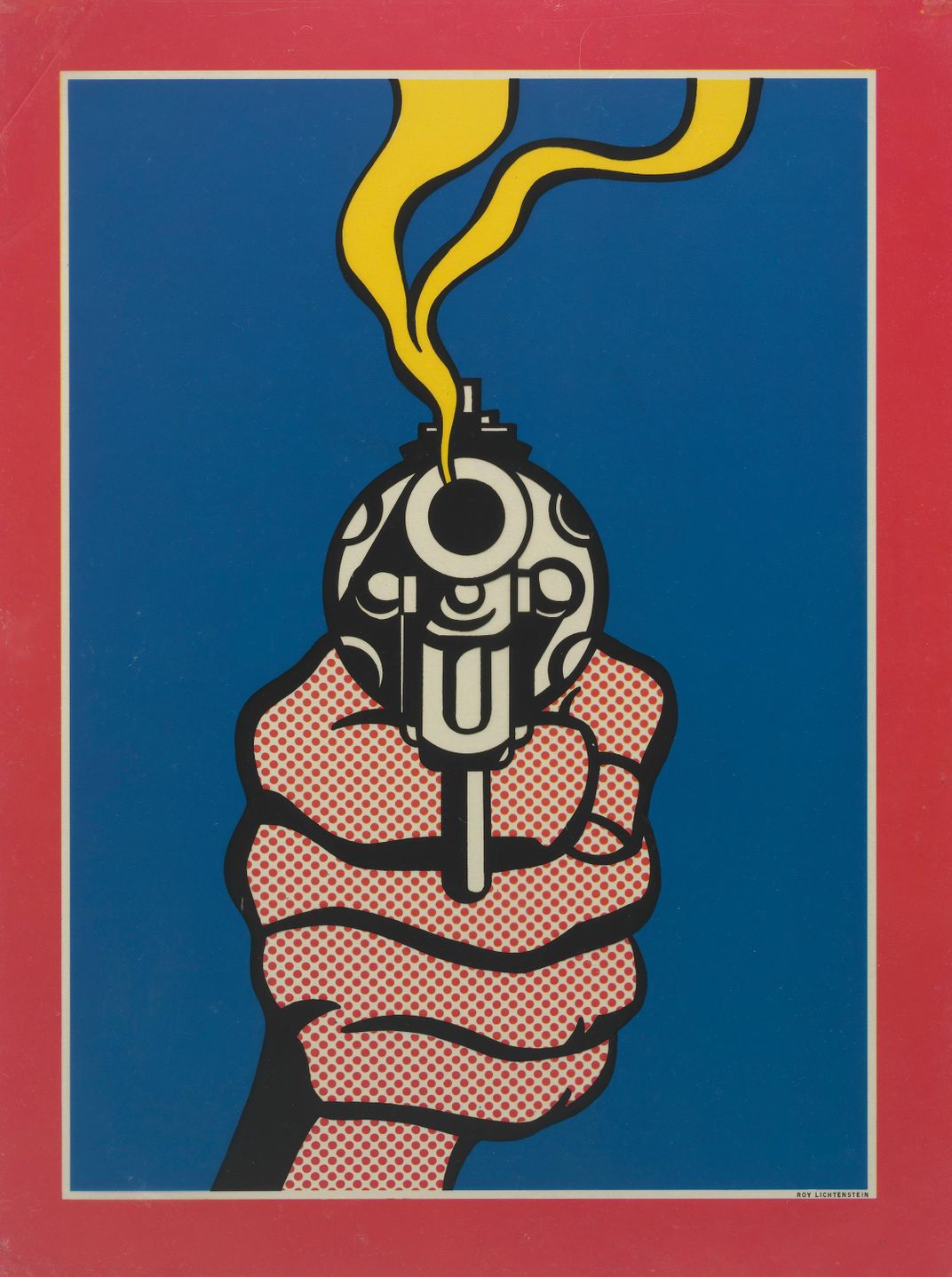

As an actor, Ronald Reagan built a reputation for being a 'good guy' tough on criminals through a form of gun vision that later served him well in his bid to become president. Two consecutive 1968 TIME Magazine covers designed by Roy Lichtenstein show Senator Robert Kennedy and a discharged gun. They were never intended as a pair, but one was on newsstands when Kennedy was killed. Lichtenstein’s art created a type of gun vision that suggested the American public were complicit in the assassination and needed to enact gun control legislation.

Finally, perhaps one of the most famous examples of gun vision involves the portrait of Clint Eastwood as Harry Callahan in the 1971 movie Dirty Harry. Eastwood’s character became an urban antihero going beyond the law to avenge the victims of violent crime. "Go ahead, make my day," was the iconic refrain as Eastwood points his weapon directly at the audience. The publicity still for the movie goes one step further, by placing the viewer at Eastwood's feet looking into his eyes as he begins to sight the barrel of the gun toward us.

As contemporary America grapples with issues of gun legislation, it is worth remembering that the history of portraiture has played its part in romanticizing firearms. From the laudatory portrait of Samuel Colt posing with his revolver in 1862, until the advent of gun vision in contemporary cinema, the desire to merge entertainment, excitement and reality, has promoted the idea that bravery, defense of personal property and individualism is inextricably linked with being armed.

Like Danny Glover's character Malachi Johnson, in the 1985 popcorn western Silverado, who helps rid a small town of injustice and face down an evil sheriff: "Now I don't want to kill you, and you don't want to be dead," Americans have long romanticized a fictive world where the threat of violence by a "good guy" is enough to end a bad situation. Unfortunately, in today's reality, we know that this is not always true.

*Editors' Note, March 29, 2018: A previous version of this article cited work by Michael A. Bellesîles claiming that gun ownership in early America was rare. Bellesîles research methodology has been discredited and the reference to his work has been removed.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/KSajet_portrait_orange_1.13.JPG)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/KSajet_portrait_orange_1.13.JPG)