Fifty Years Ago, a Rag-Tag Group of Acid-Dropping Activists Tried to “Levitate” the Pentagon

The March on the Pentagon to end the Vietnam War began a turning point in public opinion, but some in the crowd were hoping for a miracle

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/29/96/299643ed-4e04-4103-a9f1-8061f4706faf/ap_6710210243.jpg)

Late in the evening of January 14, 1967, a few of the people responsible for turning the seventh decade of the century into the cultural moment known as “The Sixties” were lounging in a small back room of the artist Michael Bowen’s San Francisco painting studio.

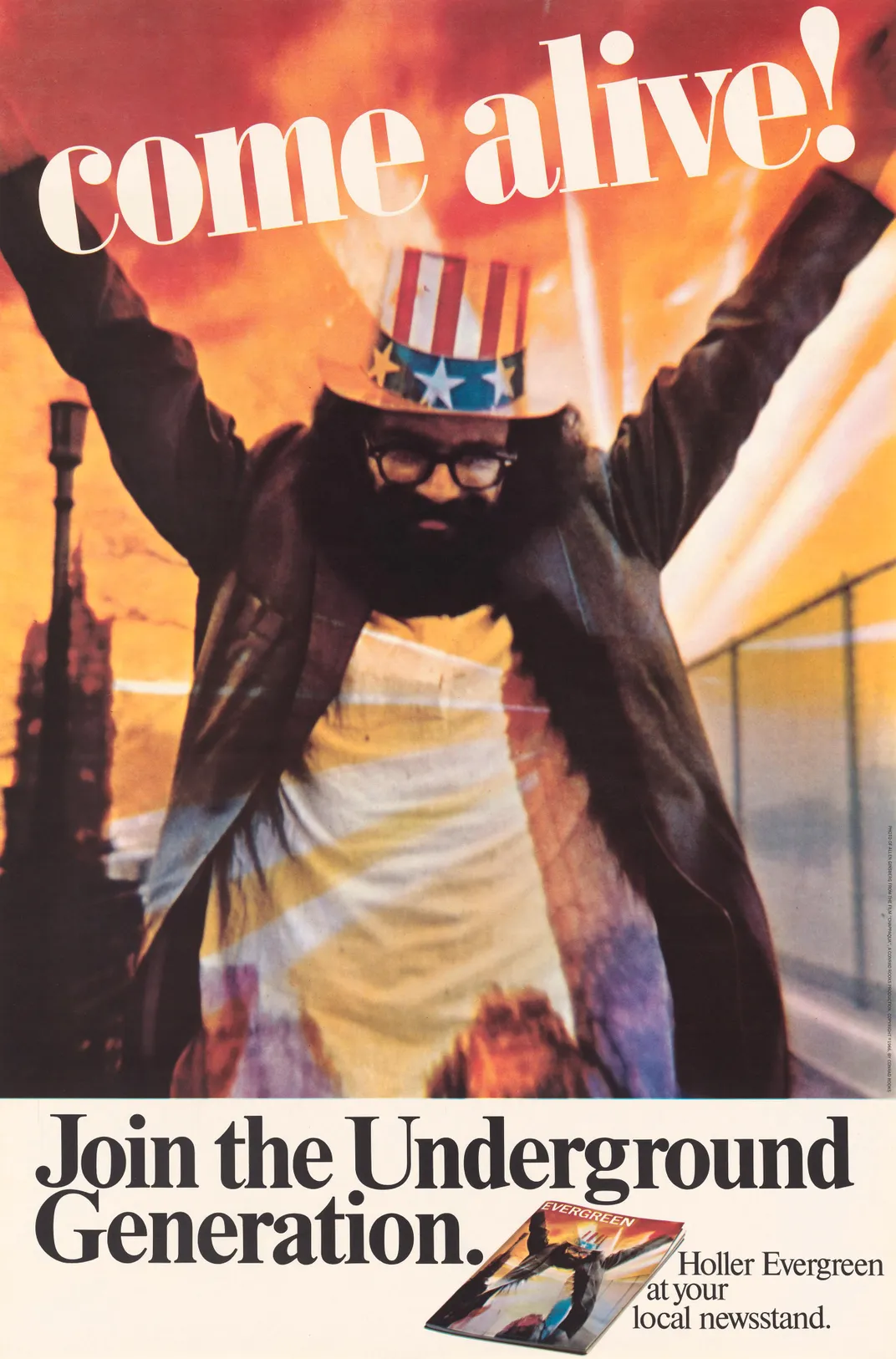

Allen Ginsberg sat cross-legged on the floor of 1371 Haight Street, passing a bottle of wine with another Beat turned hippie, the Zen poet Gary Snyder. Timothy Leary, the former professor remade as the nation’s high priest of LSD, was also there, as was the anti-war activist Jerry Rubin, who would soon join with Abbie Hoffman to start the Youth International Party, better known as the Yippies.

The March on the Pentagon celebrates its 50th anniversary this weekend and is remembered as one of the most significant political demonstrations of the era. But a look back at the gathering of a few of its organizers nine months earlier provides a window on a forgotten religious influence behind its success.

The party of about 20 1960s luminaries was a low-key affair to celebrate the day’s Human Be-In, the first large-scale summit of the counterculture, which, until then, had been largely divided between political and nonpolitical communities and other forms of dissent.

The evening’s host, a 29-year-old painter and art director of the local street newspaper, the San Francisco Oracle, Bowen was at the time considered “Mr. Haight-Ashbury” by the writer Michael McClure. He had been among the main organizers of the Be-In, but it had not been his idea. According to Bowen, that distinction belonged to the man he called his guru.

John Starr Cooke was a well-traveled American living on family money in a village near Cuernavaca, Mexico, where he and a group of followers known as the Psychedelic Rangers ingested Olympian amounts of LSD and other hallucinogens on a daily basis. Bowen had joined Cooke’s hallucinogenic order a few years earlier through an “initiation” that involved eating so many narcotic tolguacha flowers that he was left comatose and hospitalized for a month.

After his recovery, Cooke had sent his protégé as a missionary of sorts in search of fellow travelers in New York, London, and most recently San Francisco, where he had found his greatest success rallying people to the cause.

Following the Be-In, Bowen returned to Mexico to be with his teacher. They worked on extrasensory perception, ancient Mayan shamanic rituals, and the metaphysical symbology that informed the artist’s paintings. Then the guru dispatched his student back to the United States—arming him this time with an outlandish idea that found a surprisingly receptive audience.

Midway through 1967, Hoffman was looking for ways to push the mostly apolitical hippie movement toward explicitly political ends. A veteran of the Civil Rights Movement through the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, he found one way when he became involved with the National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam, an affiliated group of organizations also known as “the Mobe.” At the time, the Mobe had begun planning the largest protest yet against the war: a two-day demonstration in Washington that organizers hoped would draw 100,000 people.

The Mobe had recently hired the renowned anti-war protestor Jerry Rubin as the Washington demonstration’s project director, and the first thing the Berkeley radical did was inject a little West Coast logic into the East Coast radicals’ plans.

The initial conception of the protest had been to occupy the Capitol, but that, Rubin suggested, might send the wrong signal to the public, suggesting that the marchers wanted to shut down the democratic process and thus were offering only more political negativity. His friends behind the Be-In, he told his Mobe colleagues, had an idea for a different stage on which to perform their dissent—the Pentagon.

Even before the Be-In, Bowen had spoken to Rubin, and anyone else who would listen, about the occult significance of the five-sided pentagram and the significance that might be inscribed for it as representing evil forces at work in the world.

More than the Capitol, Rubin now agreed, the Pentagon was a natural symbol of the war. As such, it would serve as a far more resonant target.

Apprised of this new plan, another voice from the original Be-In, the poet Gary Snyder, contributed the idea that what was needed at the Pentagon was not just a protest but an exorcism.

Like a mystical arms race, Bowen went one better than Snyder and suggested that the exorcism should include a ritual that would actually lift the Pentagon off American soil and into the air. Time magazine later reported the intention of the proposed ritual would turn it “orange and vibrate until all evil emissions had fled” and the war would come to an immediate end.

Rubin, Hoffman and Bowen all shared an interest in dropping acid—Rubin had first been “turned on” in the artist’s studio the year before, and Hoffman by then was an hallucinogenic old hand. While the first two figures of this acid-dropping trio had no expectations of making a reality out of visions one might have while on LSD, they all were, however, pragmatic and theatrical activists, open to any idea that might bring attention to their cause. As such, they all recognized and respected the power of symbols.

When it came time to announce plans for the protest to be held in late October 1967, Rubin declared that they would shut down the Department of Defense because the anti-war movement was “now in the business of wholesale disruption and widespread resistance and dislocation of the American society.”

Hoffman elaborated with a description of the exorcism rite they would perform to end the war, declaring, “We’re going to raise the Pentagon 300 feet in the air.”

As another march organizer, Keith Lampe, remembered Bowen’s involvement in the planning (as recounted in a Arthur magazine’s fascinating oral history of the event): “We didn’t expect the building to actually leave terra firma, but this fellow arrived with ideas on how to make it happen.”

Following the artist’s journey to Mexico to consult with Cooke, Bowen “dropped in during one of our preparation meetings in New York,” ready to discuss the logistics and requirements of the ritual.

“What a charming moment,” Lampe said. “All of us ‘radicals’ there suddenly became ‘moderates’ because Michael really expected to levitate it whereas the rest of us were into it merely as a witty media-project.”

The ritual conducted at Pentagon on October 21, 1967, was all that and more. After a gathering before the Lincoln Memorial for anti-war speeches by luminaries including the poet Robert Lowell and the nation’s baby doctor, Benjamin Spock, tens of thousands began to march across the bridge to Virginia.

Norman Mailer was on the scene for the entirety of the protest. “The smell of [marijuana], sweet as the sweetest leaves of burning tea, floated down to the Mall,” Mailer wrote, “where its sharp bite of sugar and smoldering grass pinched the nose, relaxed the neck.”

Once they had assembled before the Pentagon, where military police and federal marshals were waiting to keep them in designated protest areas, organizers distributed a leaflet program for the ritual. Mailer reproduced it in his book Armies of the Night; other existing versions are less poetic, so there were either multiple programs available that day or Mailer has added his own literary flair:

October 21, 1967

Washington, D.C., U.S.A.

Planet Earth

We Freemen, of all colors of the spectrum, in the name of God, Ra, Jehovah, Anubis, Osiris, Tlaloc, Quetzalcoatl, Thoth, Ptah, Allah, Krishna, Chango, Chimeke, Chukwu, Olisa-Bulu-Uwa, Imales, Orisasu, Odudua, Kali, Shiva-Shakra, Great Spirit, Dionysus, Yahweh, Thor, Bacchus, Isis, Jesus Christ, Maitreya, Buddha, Rama do exorcise and cast out the EVIL which has walled and captured the pentacle of power and perverted its use to the need of the total machine and its child the hydrogen bomb and has suffered the people of the planet earth, the American people and creatures of the mountains, woods, streams and oceans grievous mental and physical torture and the constant torment of the imminent threat of utter destruction…

On the makeshift altar before the Pentagon, meanwhile, a number of competing rituals began simultaneously to unfold. Ed Sanders, of the rock band the Fugs, delivered an impromptu, sexually suggestive invocation punctuated with repeated calls of “Out, demons, out!”

Hoffman had his own ideas about the necessary elements of an exorcism. He busied himself pairing up couples to perform public displays of affection that would surround the Pentagon in communal love while Mayan traditional healers sprinkled cornmeal in circles of power, and Allen Ginsberg declaimed mantras for the cause.

Michael Bowen trucked in 200 pounds of flowers and distributed them to the crowd. When military police and marshals confronted the protesters, images of gun barrels blooming with daisies became the iconic photographs of the day.

While the building never did get off the ground, the ritual inspired by Bowen and his far-off guru John Starr Cooke in some ways succeeded, particularly as the “witty media project” most of the organizers believed it mainly to be.

Bowen’s ideas about dark metaphysical connotations of five-sided shapes goaded much of the media into the odd position of defending, on religious grounds, the architectural implications of the Department of Defense.

“Actually and expectedly, the hippies are wrong,” Time argued. “Most religions, including Judaism, Christian mysticism and occult Oriental sects, find the Pentagon to be a structure connoting good luck, high station and godliness.”

At least according to its organizers, the ritual also contributed to a transformation of perception, a turning point in public opinion about the war.

“The levitation of the Pentagon was a happening that demystified the authority of the military,” Ginsberg said. “The Pentagon was symbolically levitated in people’s minds in the sense that it lost its authority which had been unquestioned and unchallenged until then. But once that notion was circulated in the air and once the kid put his flower in the barrel of the kid looking just like himself but tense and nervous, the authority of the Pentagon psychologically was dissolved.”

Fifty years later, the ritual levitation of the Department of Defense enacted by Hoffman, Ginsberg, Rubin, Bowen and thousands of others is rightly recalled as one of the most unusual acts of political theater in American history. It’s also worth remembering that at least some gathered around the Pentagon that day actually believed it would fly.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/PManseau.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/PManseau.jpg)