How Singer Won the Sewing Machine War

The Singer Sewing Machine changed the way America manufactured textiles, but the invention itself was less important than the company’s innovative business

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/42/90/4290b1d4-bbed-47f5-af66-eef84d713bca/p66singerjn20143602web.jpg)

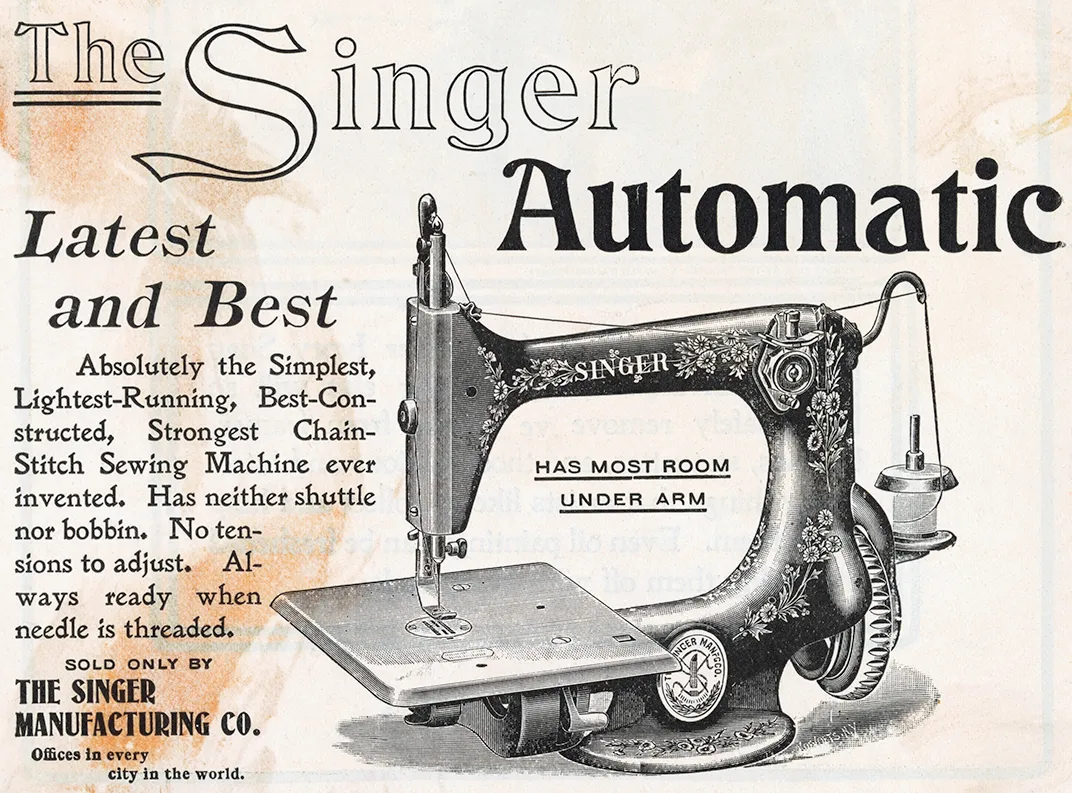

The Singer sewing machine revolutionized the way the world created and repaired its fabric, and transformed not only the textile industry, but also global business itself. But a closer look at the Singer patent model, which is on display as part of the American Enterprise show at the National Museum of American History, proves that the machine's success was not just a matter of a brilliant invention whose time had come.

“Most Americans think that if you build a better mousetrap, the world will beat a path to your door,” says the museum's Peter Liebhold, one of the curators of the new exhibition. “In fact, that’s not true. If you build a better mousetrap, it could sit and rot in the corner of your garage.”

For one thing, Isaac Merritt Singer could hardly claim to have invented the sewing machine. It was Elias Howe who created the original sewing-machine concept and patented it in 1846, charging exorbitant licensing fees to anyone trying to build and sell anything similar. But Singer—an eccentric entrepreneur, actor and father of about two dozen children from different partners—came upon a few ways to improve Howe’s model, such as a thread controller, and combining a vertical needle with a horizontal sewing surface.

Singer patented his version of the machine in 1851 and formed I.M. Singer & Co., but by then a handful of other inventors had made their own patented improvements to Howe's original concept, including the addition of a barbed needle and a continuous feeding device among other enhancements. Together all these innovations created what lawyers call a “patent thicket,” in which a number of parties can lay claim to key parts of an invention. It sparked the Sewing Machine War.

“People were suing each other and burning up their resources, fighting each other rather than developing the machine itself,” Liebhold says. Adding in the high licensing fees manufacturers had to pay, building a better mousetrap seemed hardly worth the investment.

That was when Orlando Brunson Potter, a lawyer and the president of rival manufacturer Grover and Baker Sewing Machine Company proposed an unprecedented idea: the factions could merge their business interests. Since a powerful and profitable machine required parts covered by several different patents, he proposed an agreement that would charge a single, reduced licensing fee that would then be divided proportionally among the patent holders.

Howe, Singer, Grover and Baker and manufacturers Wheeler and Wilson were all eventually convinced of the wisdom of the idea, and together they created the first “patent pool.” It merged nine patents into the Sewing Machine Combination, with each of the four stakeholders given a percentage of the earnings on every sewing machine, depending on what they contributed to the final design.

“Though the pool combined nine patents thought to be essential for a high-quality sewing machine, three of them were particularly crucial,” explains Ryan Lampe, associate professor at California State University, East Bay, who has co-written (with Stanford University Assistant Professor Petra Moser) several articles on patent pools and the Singer case in particular. He lists these as “Elias Howe’s patent on the lockstitch, Wheeler and Wilsons’ patent on the four-motion feed, and Singer's patent on the combination of a vertical needle with horizontal sewing surface.”

“It allowed the concept of the sewing machine to move forward because it was so reliant on the concept of inventions by many people,” says Liebhold. As licensing fees dropped from $25 per machine (almost half the total price) to $5 about a decade after the pool went into effect; dozens of new manufacturers entered the industry.

So, this crowdsourced sewing machine could be sold and distributed widely. But why did Singer's prove to be the one with staying power? It was not due to Isaac Singer himself, who Liebhold describes as more of a “scalawag” than a businessman. Rather, it was the smart businessmen who took charge of the company, particularly lawyer Edward Clark, who co-founded I.M. Singer & Co. He created the company’s early advertising campaigns and devised the “hire-purchase plan” for customers who could not afford the machine’s high price—the first installment-payment plan in the United States.

Clark also had the wisdom to squeeze the volatile Singer out of active management of the company, dissolving their partnership in 1863 and forming the Singer Manufacturing Company.

“There’s really a string of Singer Company executives that push it forward and it is the contribution of all of them who really formed the company and made it dominant in the field," says Liebhold.

The company expanded the practice of door-to-door sales, in part because the hire-purchase plan required canvassers to collect weekly payments, but which also allowed salesmen to bring the product into prospective customers’ homes, and show them how such a novel machine could simplify their lives. The company opened up flashy showrooms where it could demonstrate how the machines work (a scale model of an original Singer showroom will be included in the exhibit), and took machine demonstrations to county and state fairs.

Singer Co. also became active in buying up used sewing machines and tamping down secondary markets of used sewing machines. Like the latest iPhone today, Singer would roll out a new sewing machine model and encourage consumers to replace their old one.

The company’s organization was one of its other major innovations, creating a centralized bureaucracy to run its sprawling footprint. The exhibition includes a scale-model of the Singer Tower, the company’s central headquarters in Manhattan’s financial district from which it controlled and communicated with its sales agents around the world. It was one of the first corporate skyscrapers in the country and, for about a year, the tallest building in the world.

Singer Co. also aggressively went after international markets, opening factories around the world in order to minimize transportation costs and import duties.

“It seems totally obvious to us now, but the development of a multinational is itself an invention, and how you do that is tricky,” says Liebhold.

Today, where the concept of “disruption” has become so popular in business, those developing apps and new startups can look to Singer as one of the original disruptive technologies.

“Invention is a new and creative idea, but to bring it to market and get people to adopt it is tremendously difficult—often more difficult than the invention itself,” says Liebhold.

The permanent exhibition “American Enterprise” opened on July 1 at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. and traces the development of the United States from a small dependent agricultural nation to one of the world's largest economies.

American Enterprise: A History of Business in America

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alex_Palmer_lowres.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alex_Palmer_lowres.jpg)