How a Smithsonian Artifact Ended Up in a Popular Video Game

To connect with a worldwide audience, an Alaska Native community shared its story with the creators of “Never Alone”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/db/85/db85a0d5-f49d-42d3-87a6-ef4a11964576/238986000web.jpg)

For the making of the new video game, “Never Alone,” which has been garnering much attention since its release last fall, a unique collaboration emerged between Alaska’s Cook Inlet Tribal Council, the Iñupiaq people of Alaska and the educational publisher E-Line. Its enchanting story follows the trek of the young Nuna, a girl who sets out to save her village from the epic blizzards that threaten the community's way of life and along the way, an arctic fox becomes her companion, helping to keep her from harm. The game is unlike anything currently available, according to both gamers and its critics—"stunningly poignant" and "solid and heartfelt," read some of the reviews. But the tool, the bola, or tiŋmiagniasutit, that Nuna uses to harvest food, hit targets and unlock puzzles lends the game an authenticity like no other, and it was conceived from similar artifacts in the Smithsonian collections.

When the creative team at E-Line looked for an accessory for their heroine they perused parkas, boots, mittens and other items from Northwest Alaska. But they settled on the bola, as an “unusual kind of weapon because you whirl it through the sky,” according to Aron Crowell, the Alaska director of the Smithsonian Institution’s Arctic Studies Center.

“We felt like a bow and arrow was associated with a Western audience, and we wanted something unique,” says Sean Vesce, the creative director for E-Line. “We were looking for an item that we could give to the main character that she could use in her adventure.” (Disclaimer: Smithsonian Enterprises, which publishes Smithsonian magazine and Smithsonian.com, has invested in the company E-Line.)

“Far too often, actual discussion about culture in video games is shoehorned in at the last minute by developers,” says Jason Lazarus, a 34-year-old gamer who bought a PlayStation 4 in order to play “Never Alone.” “More often than not, minorities and any shred of their culture in video games only exist as broad stereotypes. ‘Never Alone’ is the polar opposite. It’s genuine, it’s unique and it conveys a respect unheard of.”

The bola is indeed a weapon, used by wheeling it around the head and then throwing it, usually into a flock of passing geese or ducks. The bola's strings and weights wrap around the neck of the bird and bring it down. But like many Alaska Native artifacts, it’s also a work of art. Strings of sinew are attached to weights made of carved bone. The result is subtle and potentially deadly.

“A lot of them are plain,” Crowell says. “But it’s generally true that Alaska Native art of this region, . . .the weapons are art, beautiful, but also useful.”

Like many weapons, the usefulness of a bola requires training. “You’re holding the weights in front of your face,” says Paul Ongtooguk, who grew up in Northwest Alaska and learned to use a bola from a friend of his father. You “hold it so the string is just above your head. It takes some time because you have to lead the birds.

“The throwing isn’t twirling around; it’s more like a fastball for a baseball player,” Ongtooguk says. “You throw it off your heel, twist your torso, and put your arm into it.”

He says that once learned, the bola is an effective weapon, especially in fog, when birds fly low. Because it makes no sound, a bola doesn’t scare off other birds. And it's far less expensive then purchasing ammunition for a gun, he says. Though sometimes, people created the traditional weapons with a modern twist—the bolas that Ongtooguk used were a far cry from the art object in the Smithsonian collections. His were made from walrus teeth and dental floss. Dental floss, Ongtooguk says, because the thin cord is “designed to work when wet.”

“It was a hard process,” says Vesce. “Especially because we couldn’t find any road map, at least within games. It took a lot of trust and a lot of time.”

To develop “Never Alone,” the team from E-Line met with elders in the Iñupiaq community. They traveled to Barrow, Alaska, and held meetings. They viewed the Smithsonian collections at the Anchorage Museum. They spoke about traditions and legacy.

“We wanted to connect with the youth, but also the worldwide audience,” says Vesce. “But from very early on in the project it was important for us to do justice to the culture.”

“What’s so amazing about creating and developing ‘Never Alone’ is that we truly brought in a community voice,” says Gloria O’Neill, Cook Inlet Tribal Council’s president and CEO. “We wanted to make an investment in our people and who they are.”

The tribal council could have invested in anything from real estate to catering, O’Neill has told the press, but she believed that video games could be a way to connect to the next generation of Alaska Natives as well as gamers all over the world, educating them about Iñupiaq culture without coming across like a classroom history lecture. In the Alaska Native community there “hadn’t been an investment in video games, at least in the United States,” O’Neill adds.

To develop “Never Alone,” the E-Line team even learned to use the bola.

“When we started the project, I didn’t even know what a bola was,” says the game's art director Dima Veryovka. “I didn’t know how it worked until we saw a video with how people hunted with the bola.” It took the video game designers days to be able to hit a stationary target, let alone a moving flock, Vesce adds.

That doesn’t surprise Ongtooguk. His teacher was “getting them nine times out of 10,” he recalls. “I don’t know how many times I threw the thing before I got a bird.”

Still, connecting with the core audience for “Never Alone” meant more than learning to use an art object cum weapon. It meant using a narrator who speaks in the Iñupiaq language, dressing Nuna in authentic clothing and making her environment and tools as realistic as possible. There were plenty of choices, but the bola stood out. “Introducing the bola was introducing the culture, the indigenous way of hunting,” Veryovka adds. “We basically borrow all of these innovations from them and incorporate them into modern life.”

“It had a specific role in hunting and it takes on a larger, almost magical role in the game,” says Crowell. The result has impressed Alaskans and gamers alike.

Nick Brewer, a 29-year-old former Alaskan, who has lived in Brooklyn for the past several years says the game feels authentic. “Plus, it was really fun to play. It’s something that I’ve actually recommended to friends with pre-teenage kids. It’s educational without being boring. It’s fun without tons of blood and gore, and it’s a pretty touching story.”

“Never Alone” has, thus far, sold well—especially for a game with no real marketing. More than a hundred thousand copies have been sold, O’Neill said. They hope to pass one million. Originally released for PlayStation and Xbox, the game was released for Mac at the end of February and will be released for the Wii system in the spring. “We wanted to make an investment in our people and who they are,” O’Neill said. “We also said that we needed to make a game for a global audience.” “World games” is a relatively new category, but one that the Cook Inlet Tribal Council, in partnership with E-Line, hopes to explore with other games like “Never Alone” in the future.

“I place a broad emphasis on cultural education,” says Smithsonian's Aron Crowell. “So this is just an exciting way to do that and it’s a technology that creates a connection to an important segment of Native culture.”

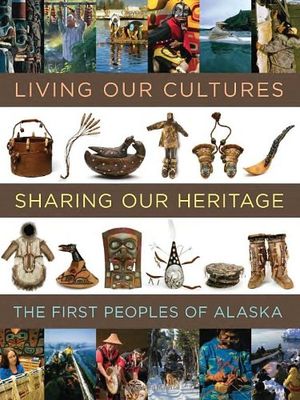

Living Our Cultures, Sharing Our Heritage: The First Peoples of Alaska

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lynne-24WEB.jpg)