As families, communities and colleagues around the world grapple in their own ways with the invisible threat of the novel coronavirus, humankind shares an unusually acute sense of traversing a period of deep historical import. Once-bustling downtown areas sit deserted while citizens everywhere sequester themselves for the common good. Social media platforms and teleconferencing services are ablaze with the messages of isolated friends and loved ones. As medical workers risk their lives daily to keep ballooning death tolls in check, musicians and comedians broadcast from their own homes in the hopes of lifting the spirits of a beleaguered nation. It is a time of both ascendant empathy and exposed prejudice, of collective fear for the present and collective hope for a brighter future.

It is, in short, a time that demands to be documented. Stories institutional, communal and personal abound, and it is the difficult mandate of museums everywhere to collect this history as it happens while safeguarding both the public they serve and their own talented team members. This challenge is magnified in the case of the Smithsonian Institution, whose constellation of national museums—19 in all, 11 on the National Mall alone—has been closed to visitors since March 14.

How are Smithsonian curators working to document the COVID-19 pandemic when they are more physically disconnected from one another and their public than ever before? The answer is as multifaceted and nuanced as the circumstances that demand it.

In recognition of the sociocultural impact of the current situation, the curatorial team at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History (NMAH) has assembled a dedicated COVID-19 collection task force even as it has tabled all other collection efforts. Alexandra Lord, chair of the museum’s Medicine and Science Division, explains that the team first recognized the need for a COVID-specific collection campaign as early as January, well before the museum closures and severe lockdown measures took effect nationwide.

They've been working with their partners since before the crisis, she says. “The Public Health Service has a corps of over 6,000 officers who are often deployed to deal with emerging health crises, some of them work at CDC and NIH. We started talking to them during the containment stage and started thinking about objects that would reflect practitioners as well as patients.”

These objects range from personal protection equipment like N95 respirators to empty boxes emblematic of scarcity, from homemade cloth masks to patients’ hand-drawn illustrations. Of course, physically collecting these sorts of items poses both logistical and health concerns—the last thing the museum wants is to facilitate the spread of COVID through its outreach.

“We have asked groups to put objects aside for us,” Lord says. “PHS is already putting objects to the side. We won’t go to collect them—we’ll wait until all of this has hopefully come to an end.”

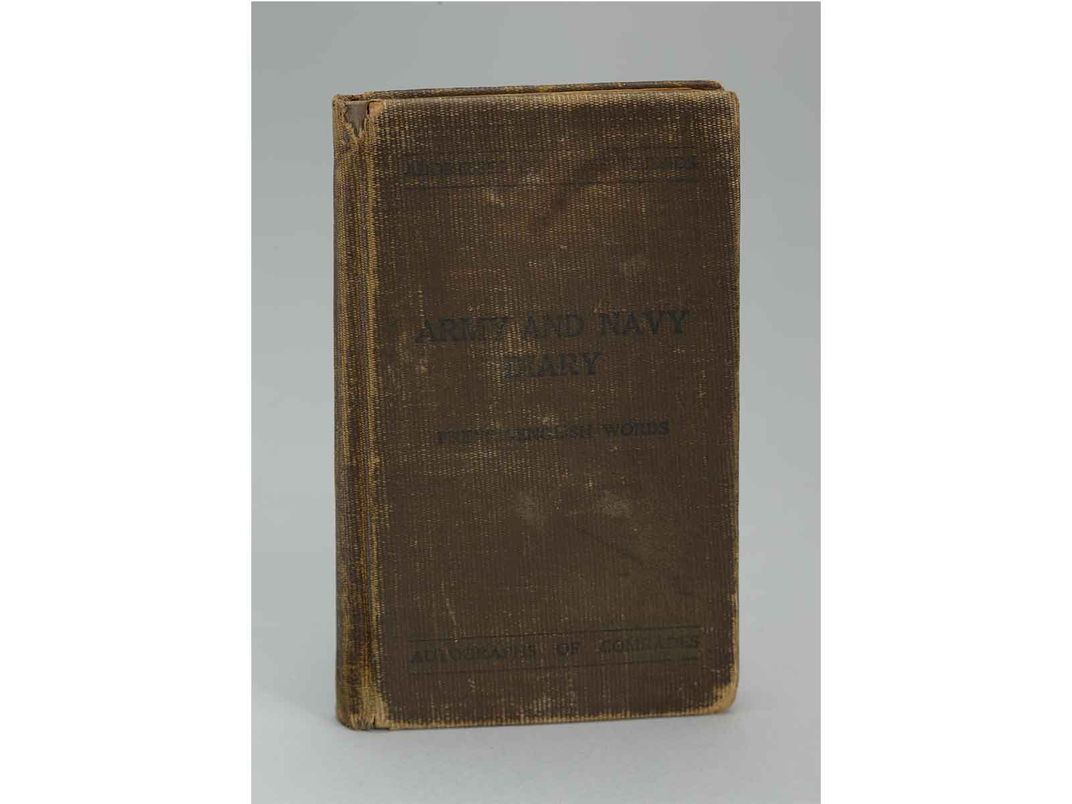

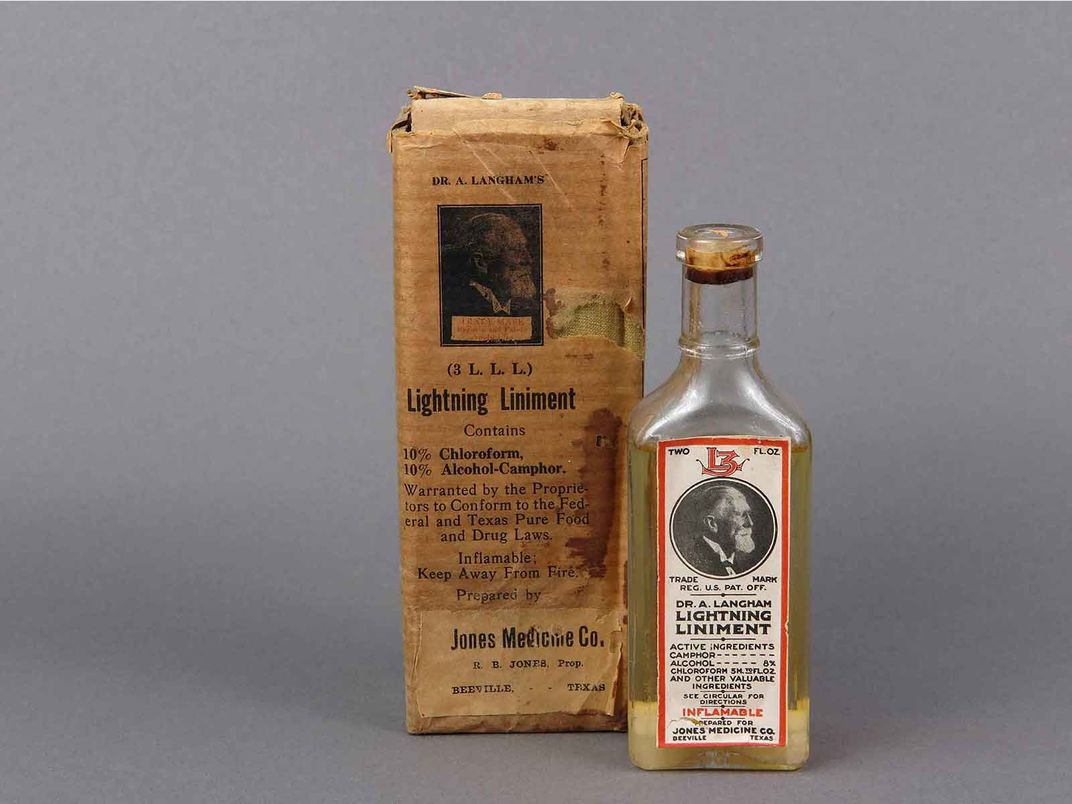

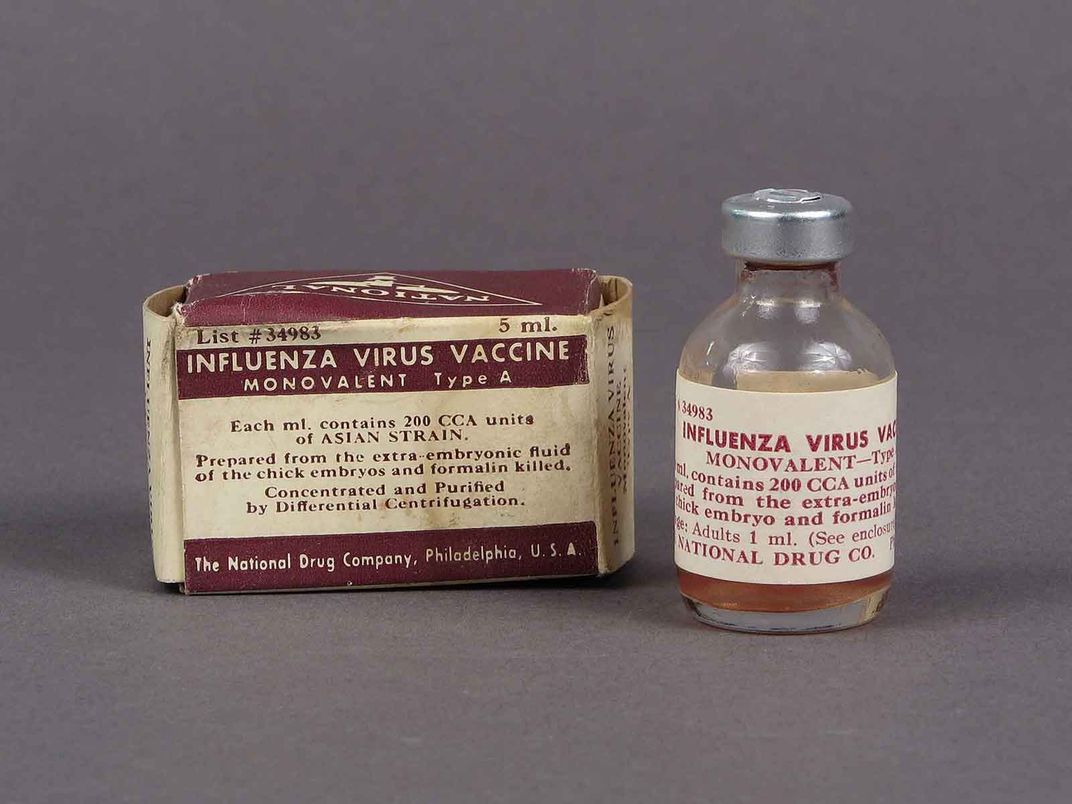

The artifacts collected in this push will feed into Lord’s upcoming “In Sickness and In Health” exhibition, a scholarly look at infectious disease in America across hundreds of years of history. Already deep in development before the COVID crisis, the exhibition—which will include studies of two antebellum epidemics and one pandemic followed by a survey of the refinement of germ theory in the 20th century—will now need a thoughtful COVID chapter in its New Challenges section to tell a complete story.

A complete medical story, that is; the economic ramifications of the coronavirus are the purview of curator Kathleen Franz, chair of the museum’s Division of Work and Industry.

Franz works alongside fellow curator Peter Liebhold to continually update the “American Enterprise” exhibition Liebhold launched in 2015, an expansive overview of American business history that will need to address COVID’s economic impact on companies, workers and the markets they serve. “For me, as a historian of business and technology,” Franz says, “I’m looking at past events to give me context: 1929, 1933, 2008. . . I think the unusual thing here is this sudden constriction of consumer spending.”

As federal and state governments continue to place limits on the operations of non-essential businesses, it is up to Franz and her colleagues to document the suffering and resilience of a vast, diverse nation. Usually, she says, “We collect everything: correspondence, photos, calendars. . . and we may collect that in digital form. But we’re still working out the process.” Above all, she emphasizes the need for compassion now that Americans everywhere are grieving the loss of family, friends and coworkers.

Museum as Educator

With many busy parents suddenly thrust into de facto teaching jobs with the closures of schools across the country, the museum has placed special emphasis on shoring up its educational outreach. From the beginning, says director Anthea Hartig, the museum “privileged K-12 units, because we knew that’s what parents would be looking for.” Some 10,000 Americans responded to a recent survey offered by the museum, with most pressing for a heightened focus on contemporary events. Now is the perfect time for the museum’s leadership to put that feedback into practice.

Hartig sees in this crisis the opportunity to connect with the public in a more direct and sustained way than ever before. Thousands have already made their voices heard in recent discussions on social media, and fans of the Smithsonian are taking on transcription projects for the museums with fresh zeal. Beyond simply livening up existing modes of engagement, though, Hartig hopes that her museum will be able to seize on the zeitgeist to make real strides with its digital humanities content. “Our digital offerings need to be as rich and vibrant as our physical exhibitions,” she says. “They should be born digital.”

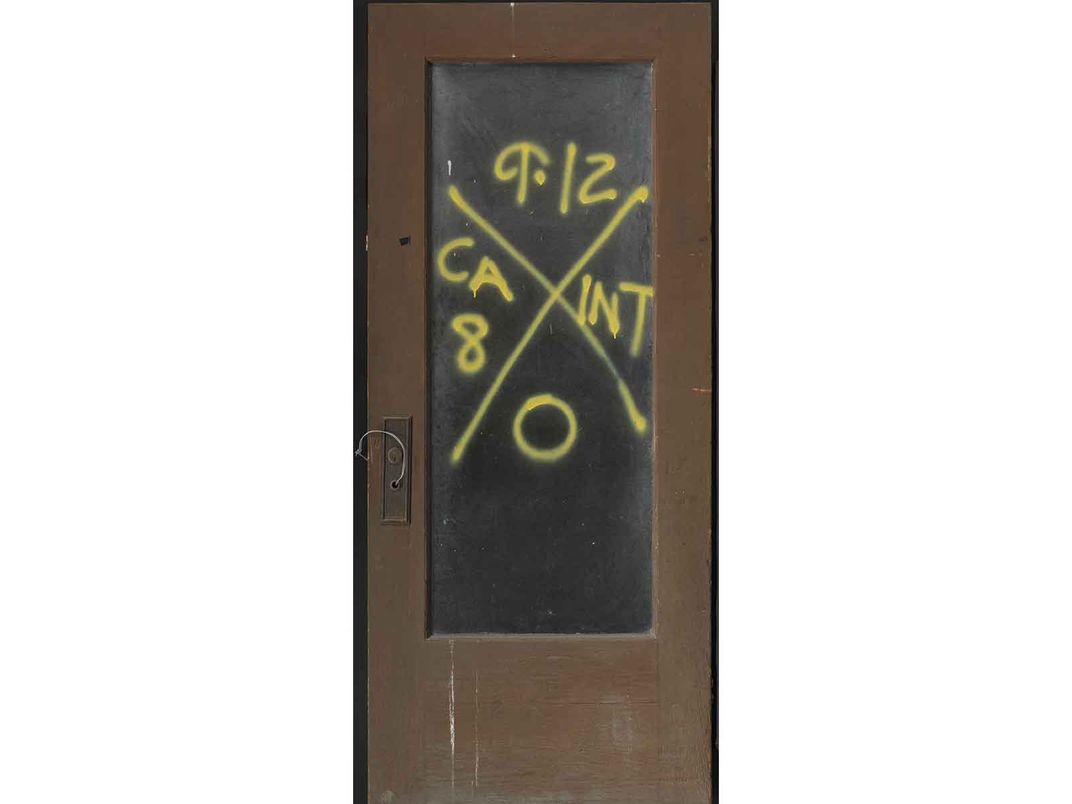

For inspiration amid all the flux and uncertainty, Hartig is reflecting on the NMAH’s response to the terrorist attacks that rocked the nation nearly 20 years ago. “We learned a lot through 9/11, where the museum was the official collecting authority for Congress,” she says. That moment in history taught her the value of “quietness and respect” when acquiring artifacts in an embattled America—quietness and respect “matched by the thoroughness of being a scholar.”

Hartig appreciates fully the impact of the COVID moment on America’s “cultural seismology,” noting that “every fault line and every tension and every inequity has the capacity to expand under stress, in all our systems: familial, corporate, institutional.” She has observed a proliferation in acts of goodness paralleled by the resurfacing of some ugly racial prejudice. Overall, though, her outlook is positive: “History always gives me hope and solace,” she says, “even when it’s hard history. People have come out through horrors of war and scarcity, disease and death.” History teaches us that little is unprecedented and that all crises, in time, can be overcome.

Inviting Participation

Benjamin Filene, NMAH’s new associate director of curatorial affairs, shares this fundamental optimism. On the job for all of two months having arrived from North Carolina Museum of History, the experienced curator has had to be extremely adaptive from the get-go. His forward-thinking ideas on artifact acquisition, curation and the nature of history are already helping the museum to effectively tackle the COVID crisis.

“For a long time, I’ve been a public historian committed to helping people see contemporary relevance in history,” he says. Against the backdrop of the coronavirus crisis, he hopes to remind Smithsonian’s audience that they are not mere consumers of history, but makers of it. “We [curators] have something to contribute,” he says, “but as a public historian, I’m even more interested in encouraging people to join us in reflecting on what it all means.”

And while hindsight is a historian’s best friend, Filene maintains that historians should feel empowered to leverage their knowledge of the past to enlighten the present as it unfolds. “I personally resist the notion that it has to be X number of years old before it’s history,” he explains. “We’ll never have the definitive answer.”

He views history as an ongoing refinement that begins with contemporaneous reflection and gradually nuances that reflection with the benefit of added time. “Even when you’re talking about something a hundred years ago, we’re continually revisiting it,” he says. “We can ask questions about something that happened five months ago or five days ago. But no doubt we will be revisiting this in five years, in 50 years.”

With that future reconsideration in mind, Filene’s priority now is the collection of ephemeral items that could be lost to history if the Smithsonian fails to act quickly. “Using our established community networks, full range of digital tools, publicity outreach,” and more, Filene hopes the museum can persuade Americans everywhere to “set aside certain items that we can circle back on in a few months.”

Paralleling the efforts of NMAH, the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) is mounting its own campaign to document the impact of COVID-19 across the country. Curator William Pretzer frames the museum’s objective as “collecting as a way of building community.” In the coming days, NMAAHC will be issuing a “plea” to “organizations, community groups, churches” and individuals to pinpoint artifacts emblematic of this time and allow the museum to collect them.

Many of these materials will be digital in nature—diaries, oral histories, photographs, interviews—but Pretzer makes clear that internet access will not be a prerequisite to participation. “We’re going to work with local organizations,” he says, “without violating social distancing, to talk to members of their communities who maybe aren’t online.” Then, at a later date, NMAAHC can employ these same relationships to preserve for posterity “the signs people put up in their stores, the ways they communicated, the works of art they created, the ways they educated their children.”

Since its founding, NMAAHC has committed itself to building relationships with African Americans nationwide and telling emphatically African American stories. Pointing to the heightened tensions of COVID-era America, Pretzer says this collection effort will offer the chance to “analyze topics we often talk about casually—the digital divide, health care, educational gaps, housing problems—under this pressure cooker circumstance, and see how communities and individuals are responding.” He stresses that the museum’s interest in these narratives is far from strictly academic. “People want to have their stories heard,” he says.

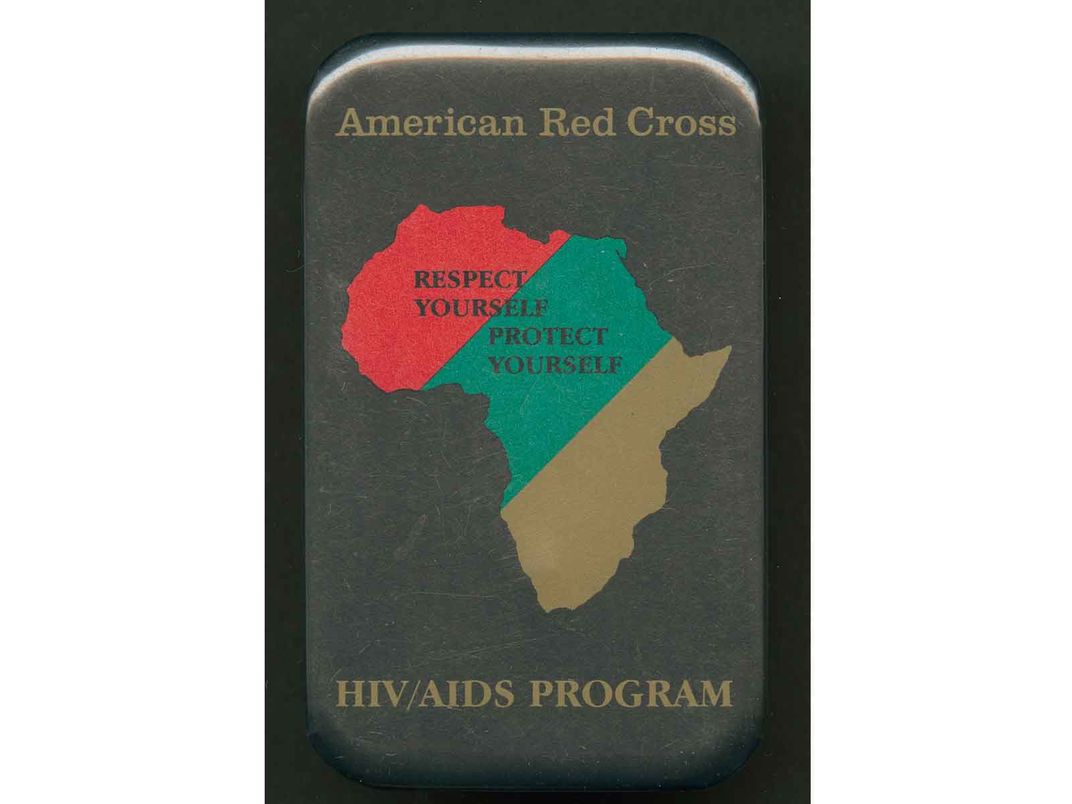

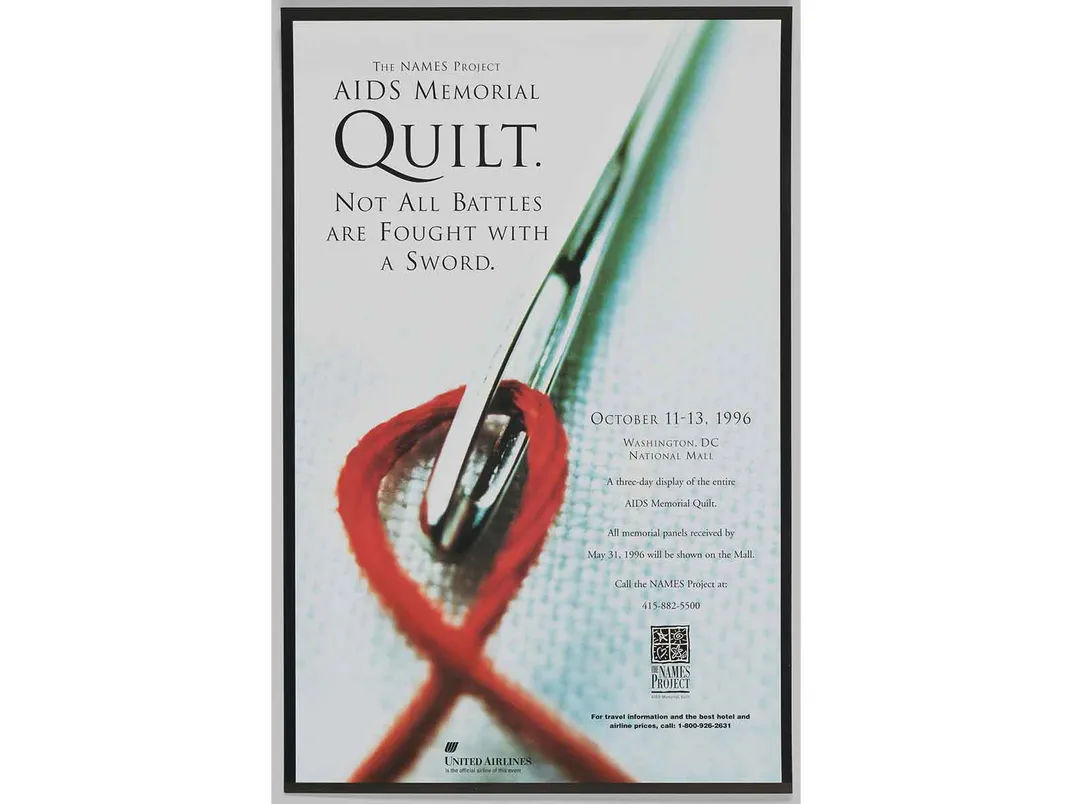

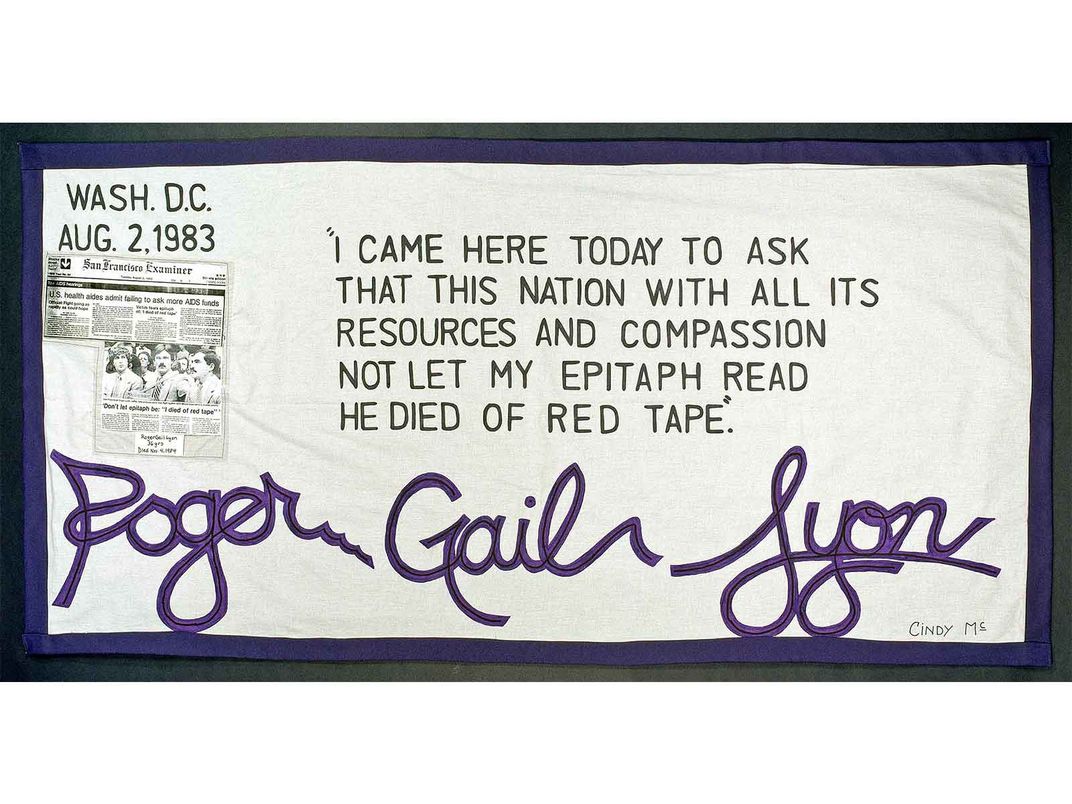

Pretzer likens this all-out community push to the one the museum mounted when collecting Black Lives Matter materials in 2014, which told a richly textured story using artifacts from community groups, business owners, activists, photographers and law enforcement personnel. “It took us to Ferguson, it took us to Baltimore,” he recalls. “That’s when we made connections with local churches." Now, as then, Pretzer and the other curators at the museum hope to uncover the “institutional impact” of current events on African Americans, “which will by nature demonstrate inequalities in lived experience.”

The Smithsonian’s curatorial response to COVID-19 extends beyond NMAH and NMAAHC, of course—every Smithsonian knowledge hub, from the Anacostia Community Museum to the National Air and Space Museum to the National Museum of the American Indian, is reckoning with COVID in its own way. But the various teams are also collaborating across museum lines like never before, supporting one another logistically as well as emotionally and sharing strategic advice. Pretzer says that roughly ten Smithsonian museums have put together “a collaborative proposal to conduct a pan-Institutional collection effort” and are currently seeking funding to make it happen. The concept is a 24-hour whirlwind collection period “in which we would try to collect from around the country the experiences of what it’s like to be under quarantine. And from that initial binge, we would create connections that would allow us to continue.”

As far as physical artifacts are concerned, all Smithsonian museums are taking the utmost care to avoid acquiring items that Americans may still need and to thoroughly sanitize what materials do come in to ensure the safety of museum staff.

“What we’re learning is to give ourselves a lot of room,” says Hartig. “We’re trying to be courageous and brave while we’re scared and grieving. But we’re digging deep and playing to our strengths.”

Ultimately, she is proud to be a part of the Smithsonian during this trying time and is excited for the Institution to nurture its relationships with all the communities and individuals it serves in the weeks and months ahead. “We’re very blessed by our partnership with the American people,” she says. “What can we be for those who need us most?”

:focal(297x134:298x135)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7d/f9/7df9ec53-f7b0-4c67-8e35-d3e07089f7da/si_graphic_mobile.jpg)

:focal(1028x304:1029x305)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c2/58/c258be29-2e9a-4769-a9ff-569e2148cd17/main_longform_si.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)