How the Smithsonian Helped Sleuth Out the True Identity of a Pair of Dorothy’s Ruby Slippers

When the FBI asked museum conservators at the American History Museum for assistance, they discovered the two pairs are twins

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/be/7c/be7c8dcb-25e0-4ce3-9a96-1f64c6b2131f/ruby_slippers_smithsonian_conservator.jpg)

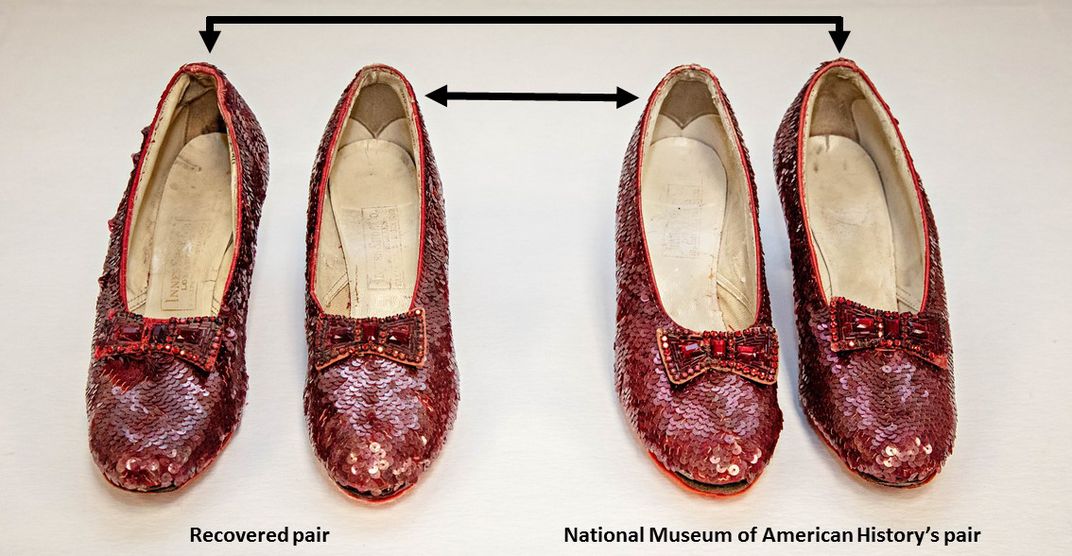

Dawn Wallace and Richard Barden stood in the museum's objects conservation lab looking over two shoes. Red. Sequin-covered. Small heels. Petite in size.

Wallace, an objects conservator, had recently spent more than 200 hours examining the museum's long-cherished pair of Ruby Slippers, worn by Judy Garland while filming the iconic 1939 movie The Wizard of Oz. Barden, the museum’s chief conservator, had spent decades with the collections, including the sparkling shoes that are slated to go back on view in a new showcase display on October 19, 2018.

Those shoes, now fully conserved thanks to the support of 6,000 Kickstarter backers who funded their preservation, were safely stored elsewhere in the museum. The shoes that sat before Wallace and Barden had been delivered by FBI agents for examination, and could be the key to a 13-year-old mystery.

"Wow, I think these are the real thing," Wallace thought.

At the FBI's request, Wallace and Barden were looking for signs that the recovered pair might be those that went missing in 2005 while on loan to the Judy Garland Museum in Minnesota. Was this pair a masterful replica, or would evidence suggest that these shoes were worn by Garland as she worked on the film?

Wallace and her colleagues would spend nearly two days poring over every detail to assist the FBI in learning as much as possible about the glistening red shoes the agents had brought to the museum.

National Museum of American History staff do not authenticate objects, but often share knowledge when asked—and, of course, relish "the opportunity to learn more about objects that are so important to American history," says Ryan Lintelman, the museum’s entertainment curator. Wallace and Barden were eager to use their expertise to determine if the recovered pair's materials, construction and condition were consistent with the museum's pair.

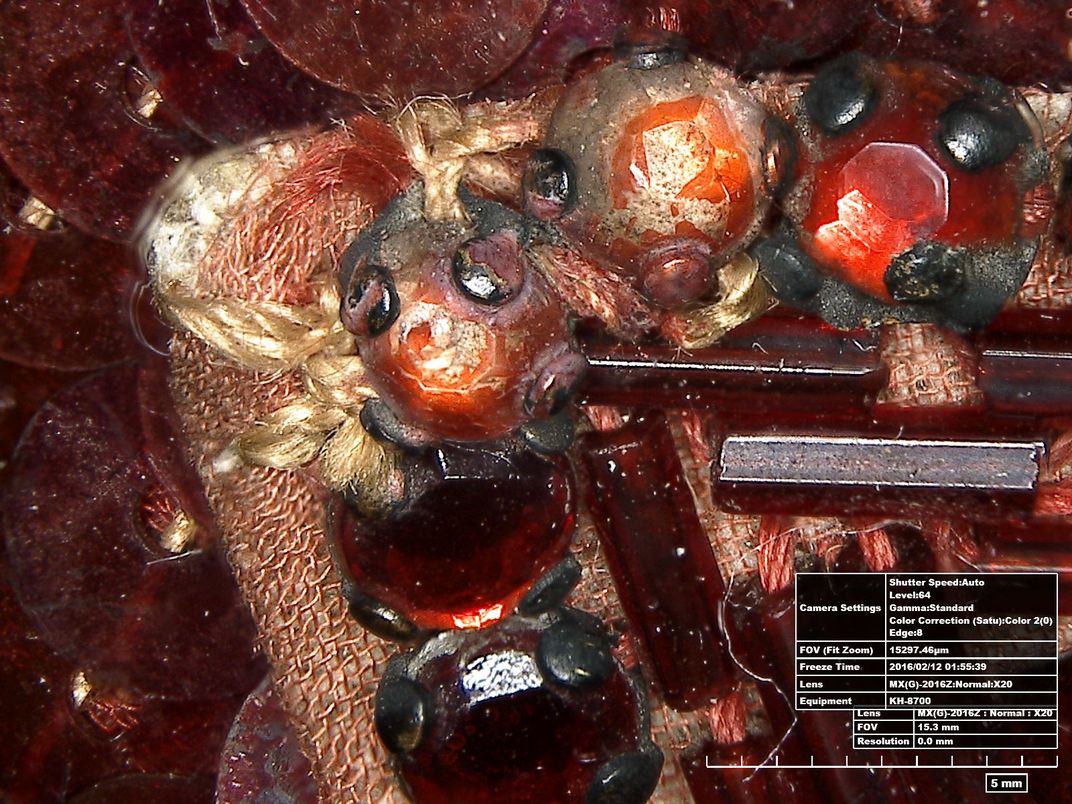

Wallace checked every inch of the shoes. Her expertise with the Smithsonian’s Ruby Slippers made her uniquely qualified to spot any minute clues the shoes may offer. The conservation work was a "sequin by sequin sequence," she likes to joke. During that process, she cleaned each sequin, realigning many to expose the silver side with more reflectance and stabilizing the shoes so that they can be on display for years to come.

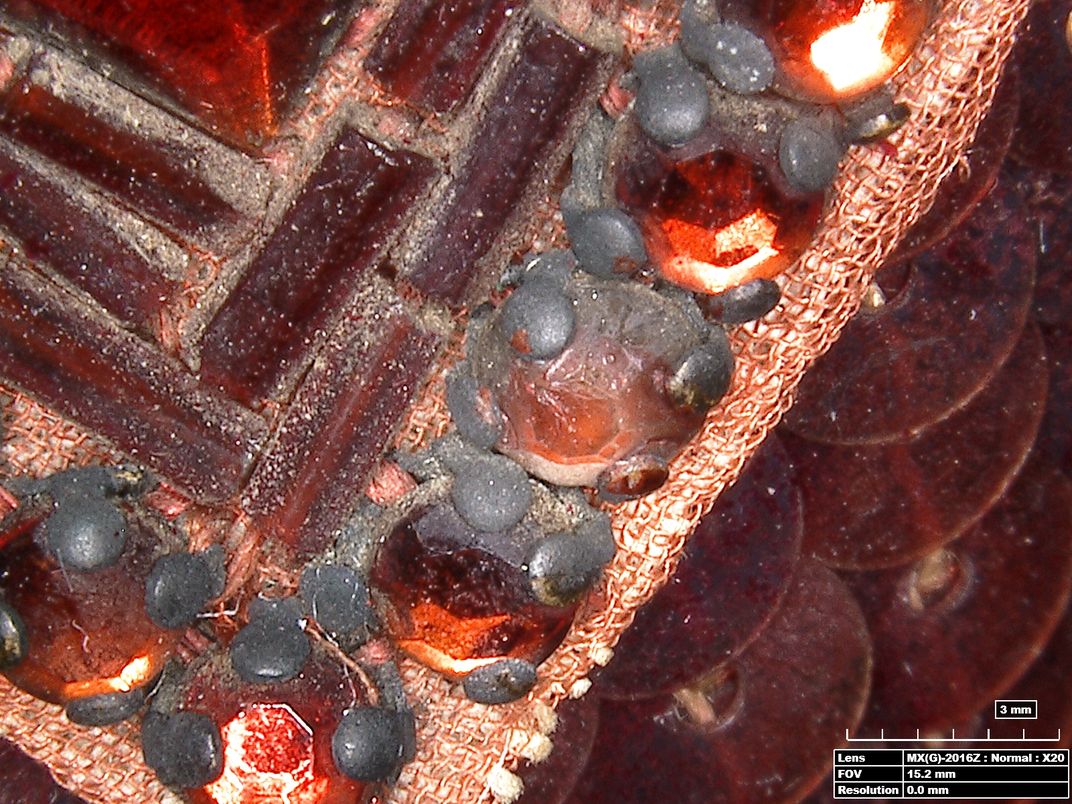

Investigating the materials and their condition, Wallace noticed many consistencies with the museum's pair. But it was a clear glass bead on the bow of the left shoe that, for her, confirmed her initial reaction.

Wallace had also spotted clear glass beads painted red while peering through a microscope during conservation work on the museum's pair. Analysis and interviews with Hollywood costumers indicated that the painted-bead replacements were likely repairs made on-set during filming.

"To me, the glass bead painted red was a eureka moment," Wallace said. "That's a piece of information that hasn't been published anywhere and, as far as I know, isn't widely known. It's a unique element of these shoes, and spotting that bead was a defining moment."

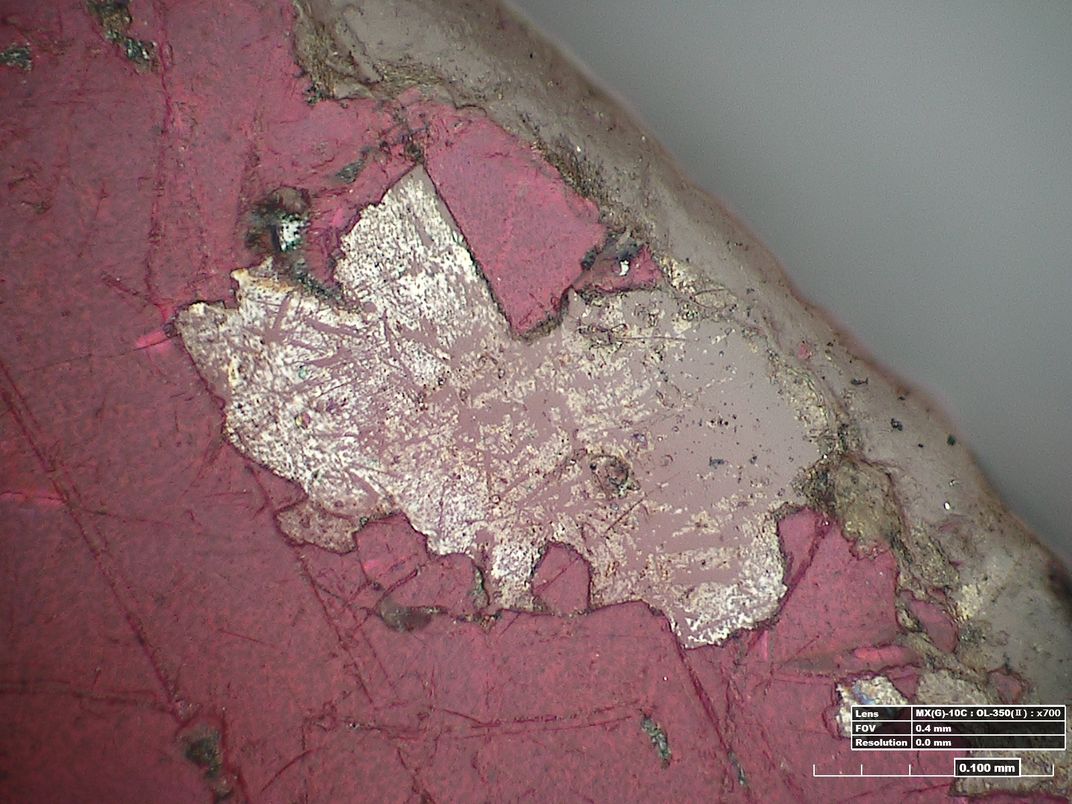

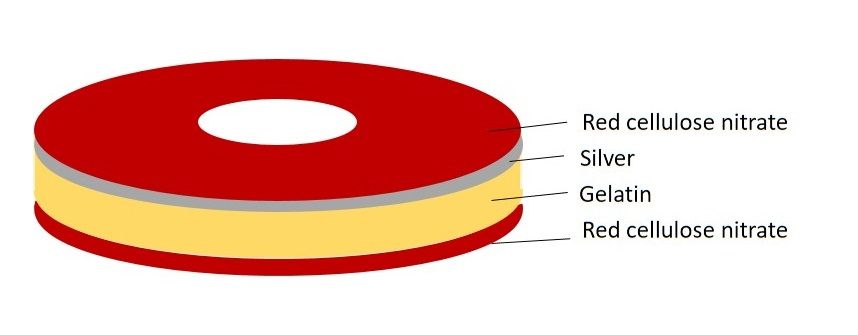

In addition to examining the shoes, Wallace worked with scientists from the Smithsonian Institution's Museum Conservation Institute (MCI) to analyze their materials using a non-destructive process. They could then compare results between the two pairs. Analysis revealed, for example, that the sequins combine layers of different materials, including cellulose nitrate and a silver backing designed to reflect light and create a sparkle. (Modern sequins have aluminum instead of silver.)

For Barden, the "aha!" moment came while examining the level of deterioration of the recovered pair's sequins. The physical and light damage is consistent with the museum's pair. To replicate this type of aging, one would have to have specialized knowledge.

"Because of our conservation work on the Ruby Slippers, we created basically a library of information about the shoes," Wallace says. "And we were able to apply that to the pair the FBI brought here and gain more information." The MCI scientists, with Wallace and Barden, plan to publish about the project in the journal Heritage Science this fall and present their findings at conferences to help other museum professionals care for objects like these.

The clear glass beads, painted red, offered another surprising insight that, unexpectedly, linked the museum's pair to the recovered pair. The museum's pair is not identical. The heel caps, bows, width and overall shape do not match; the shoes were brought together from two separate sets. But in examining the recovered shoes, conservators found the left to the museum's right and the right to the museum's left. When temporarily reunited, the four shoes created two matching pairs—twins.

It's possible the mix-up happened during preparation for the 1970 auction of items in MGM's costume closets. That's when the museum's pair was purchased—parting ways from other pairs produced for the film—and donated to the museum anonymously in 1979. Both the museum’s pair and the recovered pair have felt on the bottom for dance sequences. The Ruby Slippers that were used in the film’s close-ups would have been felt-free.

"It was a great experience to see the recovered pair of shoes, for us at the museum," Lintelman says. "The Ruby Slippers have this unique resonance with the public—people watched this movie as kids or over the holidays. . . . It's a shared experience, an adventure story, a fairy tale."

A version of this article was originally published on the museum’s “O Say Can You See?” blog. Erin Blasco manages the museum’s blog and social media.

The newly conserved Ruby Slippers from the collections of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History will return to public view on October 19, 2018. Anyone with information regarding the pair of Ruby Slippers stolen from the Judy Garland Museum is encouraged to contact the FBI.