How the Smithsonian Prepares for Hurricanes and Flooding

An emergency command center is ready for activation and the National Zoo could move animals into bunkers

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/af/98/af9814b8-0272-479e-af00-ac34adebd6cd/download.jpeg)

In his office a block from the National Mall, Eric Gentry has spent the past week monitoring updates from the National Hurricane Center and passing information to his colleagues at the Smithsonian. As Hurricane Florence makes landfall, Washington, D.C., home to the majority of the Smithsonian museums, has been receiving variable reports on the storm’s approach, including most recently threats of flooding and downed trees. If that happens, Gentry has a high-tech operations center ready to go.

As director of the Office of Emergency Management at Smithsonian Facilities, Gentry oversees a team responsible for protecting the Institution’s 19 museums and galleries, the Zoo and numerous other complexes from disasters such as hurricanes, floods and fires—such as the one that destroyed most of the collections at Brazil’s National Museum in early September. The job is particularly difficult at the Smithsonian, given how varied its sites and collections are.

“We’re dealing with multiple museums and research facilities and a very large staff in multiple locations around the world,” Gentry says. “We’re trying to support the activities of all of them and monitor what’s happening. It is far different for a smaller museum. They face the same issues, but they face them in one location and [with] one group of curators and one collection…. We’re dealing with everything from live collections to storage facilities.”

Hurricane Florence made landfall Friday, and the National Hurricane Center warned that it will likely bring “a life-threatening storm surge” and “catastrophic flash flooding” to parts of North and South Carolina. Washington D.C. and its neighboring states could experience rain and flooding, and the governors in surrounding Virginia and Maryland have declared a state of emergency.

Washington has experienced such weather before. In 2003, Hurricane Isabel caused heavy flooding, tree damage and power loss in the area. And Washington’s National Mall, home to 11 Smithsonian museums, flooded in 2006, causing millions of dollars in damage. Sections of the Mall are in the 100-year and 500-year floodplains, meaning flooding has a one in 100 or one in 500 chance, respectively, of happening there in any given year. A Smithsonian assessment listed two of the museums there as at “high” risk of storm surge flooding and two more at “moderate” risk.

“Even if we’re not in the direct path,” says Gentry, who previously was an official at the Federal Emergency Management Agency, “if you look at some of the worst damage in D.C. history, they come from the remnants of these storms.” He adds, “Areas hundreds of miles away from the hurricane can actually have the heaviest rains.”

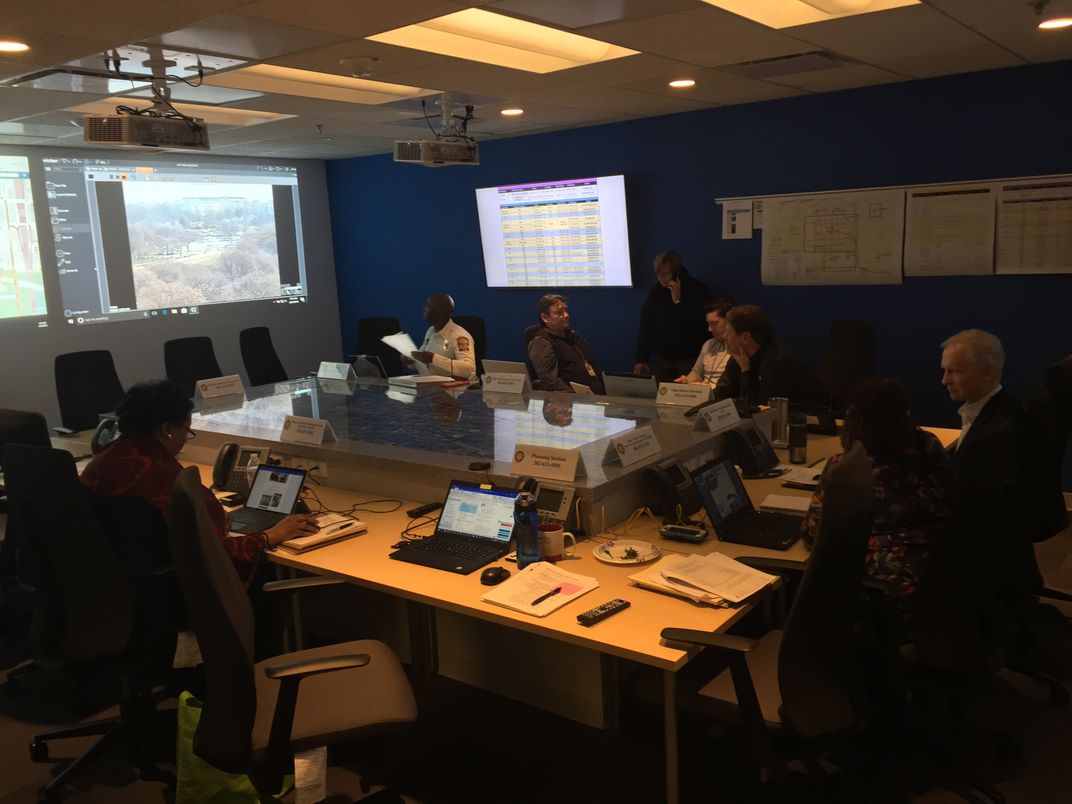

When major events happen or could happen, Gentry activates an emergency operations center at his office that includes a 20-seat room with projectors and monitors that can stream video feeds from any closed-circuit camera at the Smithsonian, from as far away as research facilities in Hawaii and Panama. At the center of the room is a table with a high-definition map of the Mall. Officials from across the Smithsonian, as well as representatives from local emergency services, come to the operations center. Recent events the team has monitored include the 2017 presidential inauguration and Women’s March, and the 2018 Stanley Cup Final games and victory celebrations in Washington.

“We’re the center hub. We hold coordination calls, pass information as we get it from the other surrounding agencies,” Gentry says. “We’re kind of the spoke of the wheel.”

But it is up to the individual museums and facilities to make their own specific emergency preparations and deal immediately with events. Perhaps the collections most vulnerable to extreme weather are at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo in Washington and the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, based in Fort Royal, Virginia, given their outdoor animals.

“Any time there’s wind, any time there’s rain, we always have to be prepared for potential wind damage or flooding,” says Brandie Smith, who as associate director for animal care sciences at the National Zoo oversees all of the 4,000 or so animals. “We can’t have a tree go down on one of our exhibits. We can’t have an animal get injured or a keeper get injured.” The Zoo also has protocols for moving animals into shelters if the wind reaches certain speeds. “Sometimes we might walk them into secure buildings,” she says, and for higher wind speeds, “we could actually put them in crates and move them somewhere where they’re more secure,” such as concrete bunkers.

To prepare for Hurricane Florence, Smith and her colleagues have been monitoring the weather “constantly” and preparing sandbags. She says staff members also have “a big red book” containing emergency instructions for how to care for an animal they don’t typically look after, if the usual keepers cannot get to the Zoo. “It’s essentially a cookbook. ‘Here’s how you take care of giant pandas,’” she says.

This week at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, which studies and breeds animals, the staff is mainly concerned about potential flooding and outdoor objects becoming airborne, according to William Pitt, the deputy director. “Securing things on a 3,200-acre site is a challenge,” he says, and they’re making sure that “everything is secure and locked down.” After weather events, they often review how they responded in order to make improvements, Pitt says. At least some of the animals there don’t mind certain severe weather; When the site received four feet of snow a few years ago, the bison “had more fun than anybody else,” Pitt says.

The museums have protocols in place, too, says Samantha Snell, a Smithsonian collections management specialist and the chair of the Preparedness and Response in Collections Emergencies team, known as PRICE. The team formed in 2016 to advise the units overseeing collections across the Smithsonian on how to prevent and handle emergencies. “Our role is trying to get everybody on the same page,” Snell says. Staff members have been identifying objects in places that could experience leaking, and “those collections are being protected or rearranged as necessary,” she says.

Last year, PRICE hosted training sessions and taught dozens of Smithsonian staff members about saving objects such as textiles and paper from water damage. Snell’s team also has a workshop on recovering from fires.

One Smithsonian museum in a location vulnerable to flooding is the newest one at the Institution—the National Museum of African American History and Culture. Not only is the building located in or near a floodplain, but also its galleries are largely underground. Brenda Sanchez, the Smithsonian’s senior architect and senior design manager, who was involved in the design and construction of the building, says Hurricane Florence will be the first major test of the museum’s flood-protection systems. “This is the first major hurricane that we have coming in this area” since the museum opened in 2016, she says, “but any other main rains that we have had have been handled very well.”

The flood-protection systems include an automatic floodgate that prevents water from reaching the loading dock, and a series of cisterns that collect and store stormwater. “Only if we got a 500-year flood we would have to do something,” Sanchez says. “If we do get to the 100-year flood, we’re ready.” She adds that the newer the building, the better positioned it can be against certain emergencies. (The Institution’s oldest building is the Smithsonian Castle, constructed in 1855.)

The Smithsonian also prepares for emergencies that can arise with less warning than a hurricane, such as the fire at Brazil’s National Museum that destroyed an estimated millions of artifacts, likely including the oldest human remains ever found in the Americas. Brazil’s culture minister has said the fire could have been prevented.

Sanchez, the Smithsonian architect and design manager, says the news of the fire made her feel “pain, a lot of pain.”

“Their cultural heritage has been lost,” says Snell, from PRICE. “It pains me to see what has happened there and what could have prevented this level of destruction.” The Smithsonian has offered to assist with the recovery efforts.

As precious as the collections are, Gentry, the emergency management director, says he is most concerned about Smithsonian visitors and employees.

Sanchez agrees. “Our first concern of course is the people, our patrons. The second concern is the exhibits,” she says. “Whatever can be done, we are doing it.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/MAx2.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/MAx2.jpg)