How Two 1950s Kids Playing on the Railroad Tracks Found a National Treasure

Curators at the National Museum of American History talked to the brothers who found a relic of the 1800 Adams and Jefferson election

:focal(784x327:785x328)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7b/1a/7b1a8fd6-c532-4976-b8e6-3a925dedda56/untitled-1.jpg)

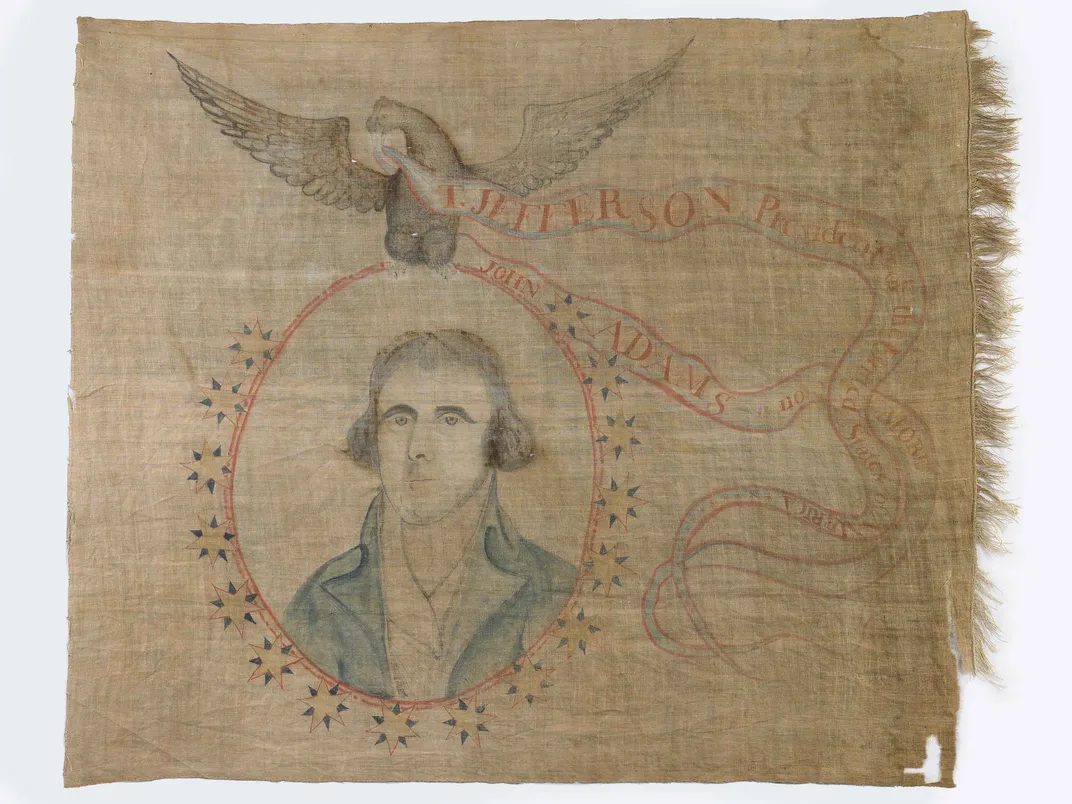

In 1959, the Smithsonian Institution received a letter from Mrs. James “Shirley C.” Wade offering to sell a linen banner bearing an ink portrait of the third president of the United States, Thomas Jefferson. An eagle carried the Jefferson portrait victoriously aloft framed in a halo of seven-pointed stars. From the bird’s beak streamed a ribbon proclaiming: “T. Jefferson President of the United States. John Adams is No More.”

The imagery was crafted in the foment of a bitter campaign that was barely resolved by a voting system so flawed (a problem later clarified by the 12th amendment) that it required congressional intervention to deliver Jefferson’s victory. During the campaign, Jeffersonian Republicans accused John Adams of conspiring to establish a new monarchy aligned with the British, and the Federalist supporters of Adams warned that the godless Jefferson would bring an end to religion in the republic. The candidates’ campaigns were so contentious in their rhetoric and accusations that historians often referred to them as an extreme example of how low presidential contests can be. Jefferson pronounced his victory the second American Revolution, and his supporters filled the streets and taverns in celebration where this banner would have added to the festivities. Jefferson’s inauguration months later would become the nation’s first test of the peaceful transfer of power from one political party to another.

Today, the banner, one of the few surviving artifacts of the 1800 election, is held in the collections of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

But how did Mrs. Wade come to own such a significant piece of American history? She reported that in 1958 her 14-year-old son, Craig, and his 11-year-old brother, Richard, discovered the relic in a railroad ditch near Pittsfield, Massachusetts. The elder son took it home and unceremoniously tacked it up on his bedroom wall. The family only realized its importance after the brothers took turns bringing it to school for show-and-tell, and their teachers both recommended showing it to a local museum.

As curators of the museum's "Division of Political and Military History," we’d always heard the story of the two boys who happened upon a national treasure, but our records focused mostly on the process of bringing the banner to the museum, not on its discovery. It seemed like a fantastical story, but was it true? Well, why not find out? These days, with the advent of social media, finding someone can be as easy as entering their name into Facebook’s search bar. In May 2018, we did just that.

“I am so amazed by the fact that you found me,” Craig Wade told us when we located him in his current home of Anchorage, Alaska. Sixty years after finding the banner on a dusty road while on summer break, Craig and Richard Wade are now both retired military; Richard has also retired from the Attleboro (Massachusetts) Police Department.

Their recollections of finding the banner were remarkably similar, both to one another and to the accounts we’d found in our files and newspaper archives, albeit with a bit more color.

A year after the boys recovered the banner, the family consulted with experts from state historical societies and professors at Harvard University. After a physical examination of the materials used and the banner’s style, the experts agreed that the artifact was authentic and that it belonged in a museum. “All of us here [at The Massachusetts Historical Society] who saw the Jefferson banner were convinced of its indubitable authenticity, and thought it a very remarkable item indeed,” reported Lyman Butterfield, editor in chief of The Adams Papers, to the Smithsonian.

Several institutions allegedly made offers to Mrs. Wade before she reached out to the Smithsonian. Newspaper reports said she was offered between $50 and $100 initially but was also told that her find was difficult to price since it was incredibly unique. In 1959, she told the Mansfield News and Times, “I don’t know whether I should sell it to the museum or keep it. And if I should sell it, should I get $100 for it, or $500, or $1000? What’s it worth?”

Thus began a two-year quest on the part of the Institution to obtain this unique treasure. The museum received the banner on a short-term loan. Museum staff conducted their own review of the banner’s materials and agreed with the findings of other experts that the banner was indeed genuine. They reached out to other institutions, including the Massachusetts Historical Society, the University of Virginia, Princeton University and Monticello to see if anyone was familiar with the object. Everyone came back enthusiastic about the piece but negative as to ever having seen it before.

To help in the acquisition of the banner the museum turned to Ralph E. Becker, a Washington attorney and a major collector of political Americana, who would eventually donate his collection to the Smithsonian. Using his political contacts, Becker arranged to have Clarence Barnes, the former Massachusetts attorney general, advise the Wade family in negotiating the banner’s sale. After going back and forth on price—Mrs. Wade initially asking for $5,000 and eventually accepting Becker’s offer of $2,000 (about $17,000 in today's dollars)—in 1961 the final agreement was made to have Becker personally purchase the banner and donate it to the museum.

Craig Wade well remembers the summer he and his brother found the banner. He recalls that his mother sent them to stay with relatives for a bit during summer break. This would represent a break for both her and the boys, who came from a family of ten children. “I was in the seventh grade in Mansfield, Massachusetts. My mother sent us for the summer, for a few weeks, to stay with my Aunt Selma and my Uncle George, who were living in Pittsfield,” explains Wade.

Their big discovery came as they were whiling away one of their afternoons. “And so we’re out doing what kids do, you know, we were walking around down by the railroad tracks in Pittsfield and there was a box there…I saw a box you know, kind of beside the railroad tracks on the bank, and so I opened it…spotted the flag, I picked the flag up, I go, 'oh, this is cool.' My brother Ricky he was throwing rocks or doing whatever, and so I put it in my jacket and went about my business…You know we were walking on the side of the railroad tracks where we weren’t supposed to be and, I think it probably fell out of a vehicle, if I had to guess. Somebody might’ve been moving,” remembers Wade.

“We were in school the next year…my 8th grade teacher, Mr. Serio, we were talking about the Revolutionary War…and he mentioned Thomas Jefferson. I raise my hand and go ‘Hey, Mr. Serio, I found a flag this summer with Thomas Jefferson on it,’ and I thought his teeth were going to fall out. He got all excited about it. He said, ‘you got what?’ And I told him the story. He said, ‘Can you bring that in and let me look at it?’ And I go, 'Yeah, I’ll bring it in tomorrow.' So I brought it into school the next morning, and I thought he was just going to pop. He just, you know lost his mind when he saw this thing…Mr. Serio looked at it and he goes, ‘Oh my God, you know what you have here?’ And I said no I have no clue, and then so he called my mom…that’s the story of it.”

Younger brother Richard had a similar recollection of throwing rocks along the railroad tracks and his own show and tell at school. “Well I was, obviously, very young, and I recall walking on the railroad tracks with my brother; he found the box and apparently took the flag out of the box. We never really thought too much of it being so young. And then we brought it home, and I believe at one point he brought it to school and the teacher was excited, and then I brought it for show and tell, I think, in my fifth-grade history class and, when I took it out of the paper bag, the teacher was speechless. And from there, you know, it just accelerated.”

The boys themselves didn’t recall having much to do with the negotiations of the sale, though Mrs. Wade was always careful to frame the flag as belonging to her son Craig and not herself. Craig remembered getting at least some compensation for his find: “I got $25 of [the purchase price] to go to Canada the next year, that’s what I got out of the banner.”

Surprisingly, the Wade children never really knew how famous their find had become. When we told Richard that it was one of the most important political banners in the country, he reacted, “Well that’s nice to hear. I’m glad it was preserved. If we’d kept it, it would’ve stayed in a paper bag up in one of the bedrooms.”

Within the family of 12, according to Richard, “It was kind of forgotten...It’s nice to hear it’s such a treasure, and it’s nice being part of something like that. A story to pass on.”

Craig echoed the thoughts many of us at the museum have had as well: “Now that I’m talking to you, it’s just pretty cool that I had a part. I mean what would’ve happened if I hadn’t been a kid and walking down the railroad track? What would’ve happened to that thing? I mean it’s amazing.”

Amazing indeed. A national treasure that only came to light because of two kids killing time on summer break.

But one mystery remains: The museum still doesn’t know how the box with the treasure came to rest along the side of the railroad.

The Jefferson banner is currently not on view.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/HarryRubensteinWEB.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Bemis_Bethanee_2.jpg)