The History of D.C.’s Epic and Unfinished Struggle for Statehood and Self-Governance

Control of the federal city was long dictated by Congress until residents took a stand beginning in the 1960s

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b5/cb/b5cb6995-5499-4357-9a5c-8536b9865a8b/votemobile1967web.jpg)

As cranes dot the Washington, D.C., skyline and new buildings open almost monthly, rapid gentrification and rebuilding is changing the landscape and demographics of the Nation’s Capital. Visitors to the federal district, whose growing population is now greater than either that of Wyoming or Vermont, often remark how much Washington, D.C. has changed in the last decade.

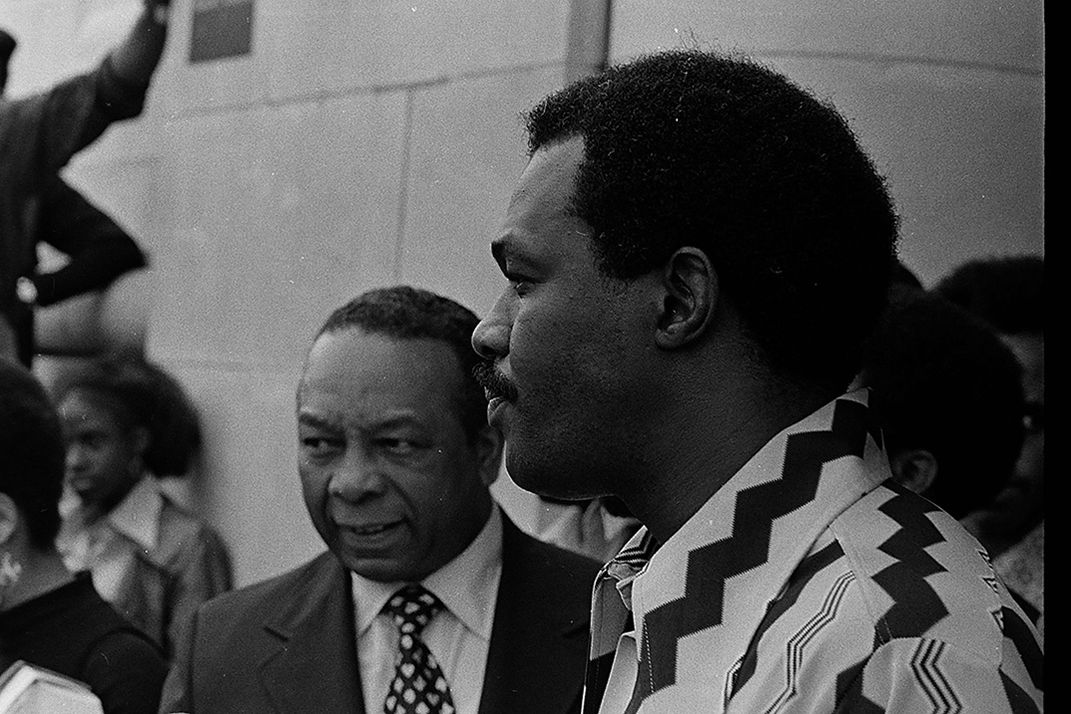

Across the 68-square-mile city, nestled on the banks of the Potomac River between Maryland and Virginia, a debate continues over statehood, control of the city’s affairs, and fair representation—a single, non-voting delegate represents its nearly 706,000 citizens in Congress. That struggle dates to a 12-year period from the early 1960s to mid-1980s, a time of uprising, protest and seismic change that finally culminated in 1975 when for the first time in a century the city’s citizens were finally able to seat a mayor and a city council.

The story of that period is the subject of the exhibition, “Twelve Years That Shook and Shaped Washington: 1963-1975,” which ran from December 2015 until October 2016 at the Smithsonian’s Anacostia Community Museum, in a neighborhood that itself is a reflection of that change.

Once a rural, sparsely populated area south of the Anacostia River, Anacostia became a predominately African-American community after whole blocks of southwest Washington, near the waterfront, were cleared for urban renewal in the early 1960s.

The museum itself, established nearly half a century ago as the Anacostia Neighborhood Museum, was an experimental outreach project that the Smithsonian Institution fostered in 1967. The vision was to speak to the American history experience from a community perspective. The facility became the Anacostia Community Museum in 2006, focusing on today’s urban issues.

“Washington’s history is traditionally told from the top down,” says guest historian Marjorie Lightman, who along with William Zeisel, her partner at the research organization QED Associates worked on the “Twelve Years” project.

Referring to the power structure of the city’s four geographical quadrants, Lightman says that governance emanates from the area that includes the federal government and the central business district. “The top is not only the White House, but the top is also the Northwest,” she says, “that’s where power has traditionally thought to have been in Washington and that’s the perspective that has always historically defined the discussion of the city.”

“Instead of talking from the hills of Northwest and looking down to the river,” Zeisel adds, “there might be some way of reversing that and starting in Southeast, Southwest, closer to the lowlands, you might say, the ordinary people, and then looking up.”

“Twelve Years” is more of a people’s history, led by senior curator Portia James, who just weeks before the opening of the show, died at age 62. James’ scholarship had long focused on the ever changing landscape of the city and she curated such popular exhibitions as “Black Mosaic: Community, Race and Ethnicity among Black Immigrants in Washington, D.C.,” “East of the River: Continuity and Change” and “Hand of Freedom: The Life and Legacy of the Plummer Family,” among others.

Washington, D.C., like many other American cities in the 1950s and 1960s, experienced a changing demographic when white families moved to the suburbs. The result of this so-called "white flight," Lightman says, was that by 1970, the city was 71 percent African American.

“It not only was the capital of the free world, it was the black capital of America,” she says. “At one point in the 1960s, it was 70 percent black.” That meant emerging black leadership as well, but at a time when the city politically had no power—everything was under the control of the U.S. Congress, as it had been for a century.

Until the district got the right to elect its first school board in 1968, Zeisel says, “Congress was running this place. I mean, they were practically voting on how many light bulbs you could have in the schools.”

It wasn’t until the 1964 elections that city residents could participate in presidential elections. “It’s only then that Washingtonians got two electoral seats,” says Lightman, “and it’s the first time Washingtonians had a meaningful voice in the presidential process.”

In 1968, an executive action by President Lyndon Johnson led to partial home rule, with the first locally elected school board elections. The first elected mayor and city council were not seated until 1975. At the inaugural that year, the city’s new mayor Walter E. Washington told the city’s residents that after decades of being treated as second-class citizens, “now we are going in by the front door!”

One of the largest federal urban renewal projects took place in the Anacostia area in the 1950 and 1960s, neighborhoods were leveled and some 600 acres were cleared in Southwest for redevelopment.

“It was the largest government-funded urban renewal in the country,” Zeisel says. “Twenty-three thousand people lived there, a majority of them poor. And when I mean cleared and flattened, I mean churches, too. It looked like the moon.”

As a result, he says, “Anacostia went from a thinly populated white population to a densely populated black population.”

The building of the Metro rail system in D.C. during that time period was important to the story, as well, although the public transit system wouldn’t officially open until 1976. It saved the city from the fate of other large cities, where whole neighborhoods were replaced by the federal highway system.

Part of that was avoided by the creation of the emergency Committee on the Transportation Crisis, established by neighborhood groups to prevent construction of freeways meant as quick thoroughfares to the suburbs. A sign from that effort, reading “White Man’s Road Through Black Man’s Home” is part of the exhibition.

Washington may have been a natural magnet for national protests in the 1960s against the Vietnam War and for Civil Rights, but by comparison there was little of the rioting that hit other cities, at least until Martin Luther King’s assassination in 1968. At that time, six days of rioting resulted in the deaths of 12, injuries to more than 1,000 and more than 6,000 arrests. Neighborhoods in Columbia Heights, and along the U Street and H Street corridors were reduced to rubble.

But that event, so often cited as the blight that stalled Washington’s progress for decades, is “not what defines the era in the city,” says Joshua Gorman, collections manager at the museum. “It’s not even what defines that year in this city.”

The blight that followed, with empty buildings along the now-popular 14th Street NW corridor and H Street NE was simply a symptom of “de-urbanization” that hit many U.S. cities in the 1970s and 1980s, when investors were less attracted to city developments and set their sights on suburbs, Zeisel says.

At the same time, the federal Community Development Corporation helped create jobs programs and organizational opportunities in various neighborhoods with school lunch and afterschool programs for students, and job finding programming for adults. It also led to the rise of black leaders from future mayor Marion Barry to Mary Treadwell, the activist who was also Barry's first wife.

With empowerment came cultural growth and Washington made its mark not only in dance and theater but music, with musician Chuck Brown and the go-go explosion, as well as in art with the homegrown Washington Color School.

Brown’s guitar is one of the artifacts in the exhibition that also includes the one of the pens President Lyndon B. Johnson used to sign the Voting Rights Act of 1965. A display in the lobby of 10 posters, some protest and some merely decorative by prominent D.C. artist and printmaker Lou Stovall serves as prelude to “Twelve Years.”

A number of audio files and video are also available to play. Among them is a 1964 film from the American Institute of Architects extolling the virtues of urban renewal, “No Time for Ugliness,” and a 1971 film about the role of community engagement in improving police-community relations, “The People and the Police,” from the U.S. Office of Economic Opportunity.

For all the progress made in the period covered by “Twelve Years,” there remains more yet to do before Washington D.C. residents obtain the kind of representation enjoyed by the rest of the country.

As such, museum director Camille Giraud Akeju says, “Never has there been a more important moment to engage Washingtonians in the history of the city and especially of this immediate past.”

“Twelve Years That Shook and Shaped Washington: 1963-1975” ran through Oct. 23, 2016 at the Smithsonian’s Anacostia Community Museum, 1901 Fort Place SE, Washington, D.C. Information: 202-633-4820.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)