How Women Got the Vote Is a Far More Complex Story Than the History Textbooks Reveal

An immersive story about the bold and diverse women who helped secure the right to vote is on view at the National Portrait Gallery

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/08/10/08100693-85d4-4757-ac9a-a224be6d42a4/cexhsu76.jpg)

History is not static, but histories can paint a picture of events, people and places that may end up being forever imprinted as the “way it was.” Such has been the case with the tale of how women secured the right to vote in America. A new exhibition “Votes for Women: A Portrait of Persistence,” on view through January 2020 at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery, aims to expose and correct the mythology that has informed how most Americans have understood the suffrage movement.

“Votes for Women” offers a wide-ranging overview—through 124 paintings, photographs, banners, cartoons, books and other materials—of the long suffrage movement that originated with the abolitionist movement in the 1830s.

The show’s ample 289-page catalog provides rigorously-researched evidence that the history we’ve relied on for decades, delivered in grade school civics classes was in part myth, and, a literal white-washing of some of the movement’s key players.

White suffragists frequently sidelined the African-American women who advocated and agitated just as much for their own voting rights. These activists endured a dual oppression because they were black and female. “This exhibition actually tries to take on the messy side of this history, when women were not always supportive of each other,” says Kim Sajet, the museum’s director.

In the catalog’s introduction, exhibition curator Kate Clarke Lemay writes “Votes for Women” is designed to help Americans “think about whom we remember and why,” adding, “Today, more than ever, it is critical to consider whose stories have been forgotten or overlooked, and whose have not been deemed worthy to record.”

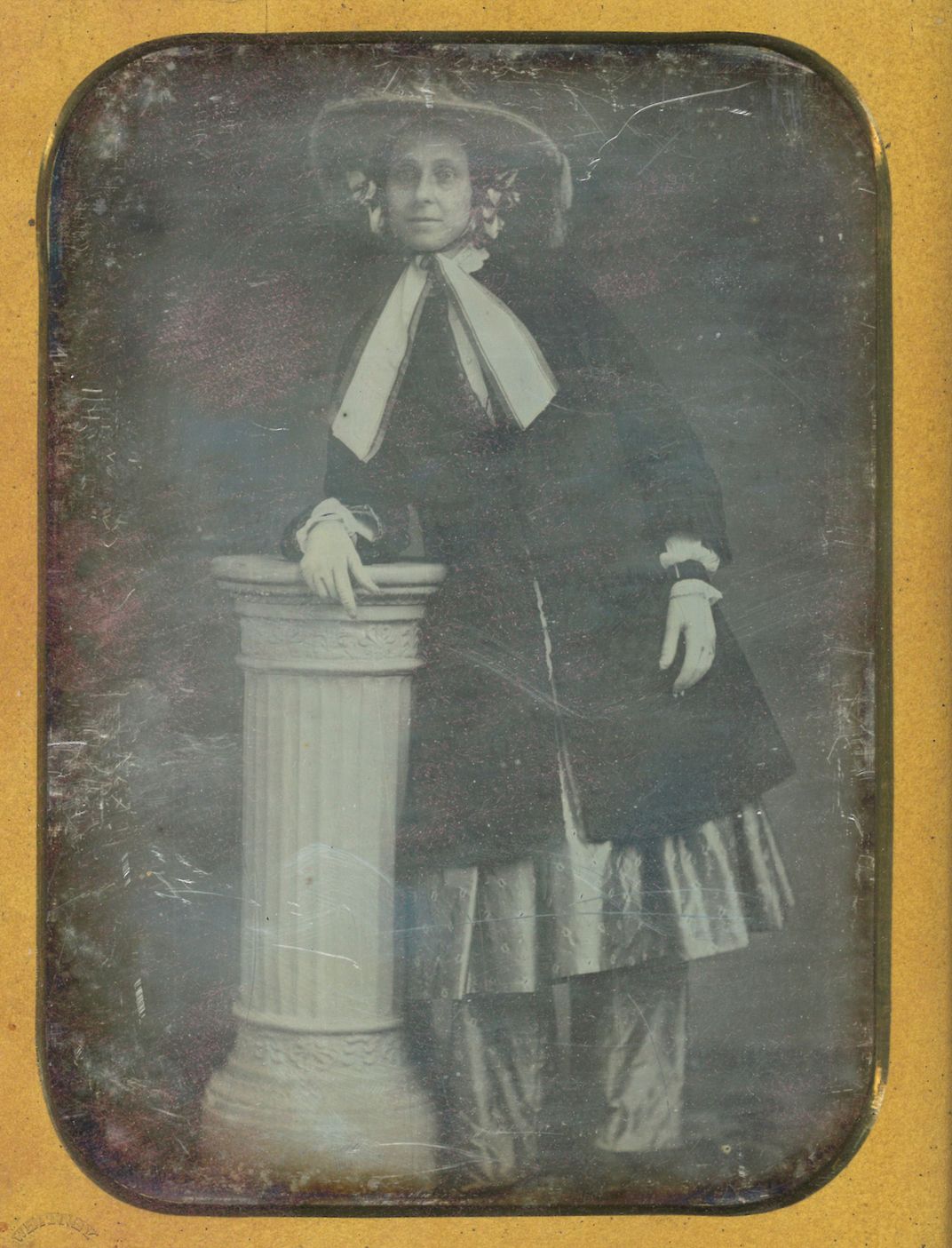

Lemay chose to feature portraits of 19 African-American women. Locating those portraits wasn’t easy. Just as they were often erased from histories of the suffrage movement, black women were less frequently the subjects of formal sittings during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Lemay says.

The overall show is a bit of an anomaly for a museum not dedicated to women, Lemay says. With the exception of one woman’s husband, the exhibition doesn’t include any portraits of men. A pantheon of key suffragists hangs in the entry hallway, featuring the well-known Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Alice Paul and Carrie Chapman Catt, along with the lesser known activists Lucy Stone and Lucy Burns. Also present as members of this pantheon are black women, including Sojourner Truth, Mary McLeod Bethune, Ida B. Wells, Mary Church Terrell and Alice Dunbar Nelson.

Votes for Women: A Portrait of Persistence

Bringing attention to under-recognized individuals and groups, the leading historians featured in Votes For Women: A Portrait of Persistence look at how suffragists used portraiture to promote gender equality and other feminist ideals, and how photographic portraits in particular proved to be a crucial element of women's activism and recruitment.

“One of my goals is to show how rich women’s history is and how it can be understood as American history, and not marginalized,” says Lemay. Take for example, Anna Elizabeth Dickinson, who was a highly celebrated speaker on the lecture circuit during the 1870s.

Renowned for inspiring hundreds of men and women to take up the suffragist cause, Dickinson is the center figure in an 1870 lithograph of seven prominent female lecturers, titled Representative Women by L. Schamer. At age 18, Dickinson began giving speeches, eventually earning more than $20,000 a year for her appearances and becoming even more popular than Mark Twain.

And yet, “who do you remember today?” asks Lemay.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ed/7f/ed7f0ed0-57a9-4556-92d1-78d9b0369632/representativewomenr.jpg)

The Myth of Seneca Falls

Elizabeth Cady Stanton started her activism as an ardent abolitionist. When the 1840 World’s Anti-Slavery Convention in London devolved into a heated debate about whether or not women should be allowed to participate, Stanton lost some faith in the movement. It was there that she met Lucretia Mott, a longtime women’s activist, and the two bonded. Upon their return to the United States, they were determined to convene a women’s assembly of their own.

It took until 1848 for that meeting, held in Seneca Falls, New York, to come together with a few hundred attendees, including Frederick Douglass. Douglass was pivotal in getting Stanton and Mott’s 12-item Declaration of Sentiments approved by the conventioneers.

Three years later, Stanton recruited a Rochester, New York, resident, Susan B. Anthony, who had been advocating for temperance and abolition, to what was then primarily a women’s rights cause.

Over the next two decades, the demands for women’s rights and the rights of free men and women of color, and then, post-Civil War, of former slaves, competed for primacy. Stanton and Anthony were on the verge of being cast out of the suffragist movement, in part, because of their alliance with the radical divorcée Victoria Woodhull, the first woman to run for president, in 1872. Woodhull was a flamboyant character, elegantly captured in a portrait by the famed photographer Mathew Brady. But it was Woodhull’s advocacy of “free love”—and her public allegation that one of the abolitionist movement’s leaders, Henry Ward Beecher, was having an affair—that made her kryptonite for the suffragists, including Stanton and Anthony.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0c/98/0c985cd0-74e7-4ea9-a765-08227140f3ec/exhsu91.jpg)

A quarter of a century after the meeting at Seneca Falls took place, memory of the event as a pivotal moment for woman’s suffrage was “almost non-existent,” writes women’s history scholar Lisa Tetrault in the catalog. “Some of the older veterans still remembered the event as the first convention, but they attached no special significance to it,” she writes. “Almost no one considered Seneca Falls the beginning of the movement.”

Stanton and Anthony needed to re-establish their bona fides. “If they originated the movement, then it stood to reason that they were the movement,” writes Tetrault. So, according to Tetrault, they fashioned their own version of an origin story about the movement and inflated their roles.

Stanton and Anthony reprinted the 1848 proceedings and circulated them widely to reinforce their own importance. With Anthony presiding over the 25th anniversary celebration, she almost by osmosis implicated herself into the founding story. “Anthony had not even been at the famed 1848 meeting in Seneca Falls. Yet newspapers and celebrants alike constantly placed her there,” writes Tetrault. Anthony herself never claimed to have been at Seneca Falls, but she became accepted as one of the founders of the suffragist movement, notes Tetrault.

In the 1880s, the pair collaborated on the 3,000-page multi-volume History of Woman Suffrage, which furthered their own self-described iconographic places in the movement. The History left out the contributions of African-American women.

“To recount this history strictly according to the logic of the Seneca Falls origin tale is, in fact, to read the end of the story back onto the beginning,” writes Tetrault. “It is to miss just how contested and contingent the outcome was, as well as how important history-telling was to the process.”

Even today, Stanton and Anthony are lightning rods. New York City’s Public Design Commission in late March approved a design for a statue of the two—commemorating them as the originators—to be placed in Central Park. The statute has drawn criticism for ignoring the hundreds of other women—black, Latina, Asian and Native Americans—who contributed to the movement.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/45/db/45dbb935-9891-43b6-bc53-239f381613d8/nine-african-american-women-w-nannie-burroughs.jpg)

The Split

The clash and upcoming schism between white and black suffragists would perhaps be previewed at an 1869 American Equal Rights Association meeting, when Stanton “decried the possibility that white women would be made into the political subordinates of black men who were ‘unwashed’ and ‘fresh from the slave plantations of the South,’” writes historian Martha S. Jones in the catalog.

It was a shocking speech to hear from someone who first gained notoriety as an abolitionist. Stanton was railing against the 15th Amendment, which gave men the vote, without regard to “race, color or previous condition of servitude.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2e/73/2e734b86-bdfb-46c7-8531-273191d87dbd/exhsu07.jpg)

Francis Ellen Watkins Harper, an African-American teacher and anti-slavery activist, spoke out at that meeting. “You white women speak here of rights. I speak of wrongs,” she said. To black men, she said she “had felt ‘every man’s hand’ against her,” Jones wrote. Watkins Harper warned that “society cannot trample on the weakest and feeblest of its members without receiving the curse of its own soul.”

The damage was done, however. White women divided their efforts into the American Woman Suffrage Association, led by Lucy Stone, who advocated for universal suffrage, and the National Woman Suffrage Association, led by Anthony and Stanton.

African-American women lobbied for their rights through their churches, and through women’s groups, especially in the Chicago area, where so many free men and women migrated from the oppression of the post-Reconstruction South.

In the 1890s, as the Jim Crow laws took effect in the South—and lynchings gave rise to terror—black women found themselves fighting for basic human rights on multiple fronts. Seventy-three African-American women gathered in 1895 for the First National Conference of the Colored Women of America. Soon thereafter, journalist Ida B. Wells and teacher Mary Church Terrell formed the National Association of Colored Women, which became a leading women’s rights and black woman suffragist organization.

Meanwhile, Stanton and Anthony saw the need to reinvigorate their efforts. They found new funding from an unlikely source, the bigoted railroad profiteer George Francis Train. “They made their bed with a known racist and then basically tainted themselves for the rest of history,” says Lemay. But, the two may have felt that they had no choice—it was take his money or let the movement die.

Lemay says that despite all this, she believes that Stanton and Anthony are deserving of significant credit. “It is clear that they were brilliant logistical and political tacticians,” she says. “They haven’t been revered as such, but they absolutely should be. They kept the movement alive.”

The Breaking Point

By the time Stanton and Anthony died in 1902, and 1906, respectively, the movement over the next decade took on more urgency. Women were becoming a social force, riding bicycles, wearing pantaloons and challenging society’s normative views of how they should act. One of the first feminist writings appeared, the 1892 short story, The Yellow Wallpaper by Charlotte Perkins Stetson Gilman, delivering a tale of a woman’s slow descent into insanity, a victim of a patriarchical society.

But powerful voices upheld the status quo. Former President Grover Cleveland denounced women’s suffrage as “harmful in a way that directly menaces the integrity of our homes and the benign disposition and character of our wifehood and motherhood.”

Alice Stone Blackwell, daughter of Lucy Stone, had helped to unite the National and American suffrage associations in 1890, and became one of its leaders in 1909. The group advanced a universal suffrage agenda and lead the way towards the passage of the 19th amendment in 1920, but the organization’s leadership positions were closed to black women.

By this time, referendums in western states had gradually awarded women the vote, but in the East multiple state referenda failed, significantly in New York. Now, women looked to take national action with a Constitutional amendment. Evelyn Rumsey Cary responded with an art deco oil painting, Woman Suffrage, that became iconic. A young, gowned female figure looms over what appears to be the U.S. Supreme Court, arms upraised to become tree branches bearing fruit.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/15/22/1522c511-7588-4990-9799-4622e40cf829/exhsu172.jpg)

In 1913, Alice Paul and Lucy Burns founded the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage to bear down on the federal government. Paul, who had studied in England, brought the British movement’s radical tactics back to the U.S. She and Burns organized a huge march on Washington in 1913. On the day before Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration, some 5,000 women participated, while 500,000—mostly men—looked on. Many attacked the women in anger. The pageantry of the Woman Suffrage Procession—including a Joan of Arc on horseback and a gowned Columbia (the allegorical symbol of the U.S.)—garnered huge national attention.

Wilson, however, was unmoved. In March 1917, Paul’s Congressional Union joined with the Women’s Party of Western Voters to create the National Woman’s Party, with the aim of a concerted campaign of civil disobedience. The White House—and by extension, Wilson—became their primary target. Women—wearing suffragist tri-colored sashes and holding banners—began picketing along the White House fence line. Action came quickly. In April 1917, just days before the U.S. entered World War I, the “Anthony Amendment”—which would give women the right to vote and was first introduced in 1878—was reintroduced in the Senate and House.

Even so, the “Silent Sentinels,” as the newspapers called them, continued their protests. Questioning Wilson’s commitment to democracy at home during a time of war outraged many Americans. Anger at the suffragists hit a boiling point on July 4, 1917, when police descended on the White House sidewalk and rounded up 168 of the protesters. They were sent to a prison workhouse in Lorton, Virginia, and ordered to do hard labor.

Burns, Paul, and others, however, demanded to be treated as political prisoners. They went on a hunger strike to protest their conditions; guards responded by force-feeding them, for three months. Another group of suffragists was beaten and tortured by guards. The public began to have regrets. “Increasing public pressure ultimately led to the suffragists’ unconditional release from prison,” writes Lemay.

Meanwhile, during the war, women were taking on men’s roles. The National Woman Suffrage Association—hoping that women’s war-related labor would be rewarded with the vote—funded an entirely self-sufficient 100-woman-strong unit of physicians, nurses, engineers, plumbers and drivers who went to France and established several field hospitals. Some of the women received medals from the French military, but they were never recognized during the war or after by the American military. To this day, says Lemay, the only woman to be awarded the Medal of Honor is Mary Edwards Walker—and it was rescinded, but she refused to give it back.

Finally, the federal suffrage amendment—the 19th Amendment—was approved in 1919 by Congress. It was then sent on to the states for ratification.

That 14-month ratification battle ended when Tennessee became the 36th state to approve the amendment, in August 1920. Afterwards, a smiling Paul was captured raising a glass of champagne in front of a banner that kept track of the states ratifying the amendment.

The Legacy

While the 100th anniversary of that achievement will be celebrated in 2020, for many women, full voting rights did not come until decades later, with the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965. Many states had found loopholes in the 19th Amendment that they believed allowed them to levy poll taxes or demand literacy tests from prospective voters—primarily African-Americans. Native-Americans weren’t recognized as U.S. citizens until 1924, but also have endured discrimination at the polls, as recently as the mid-term elections of 2018, Lemay points out, when North Dakota required anyone with a P.O. box or other rural address to secure a numbered street address to vote. The law disproportionately had an impact on Native-Americans on tribal lands, where the required street addresses are not used. In Puerto Rico, literate women could not vote until 1932; universal voting became law three years later. Activist Felisa Rincón de Gautier helped secure that right.

“Votes for Women” recognizes some of the other suffragists who took up the cause for their people, including Zitkala-Sa, who fought for Native American citizenship rights and later founded the National Council of American Indians, and Fannie Lou Hamer, a leader in the Civil Rights movement. Patsy Takemoto Mink, the first woman of color elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, is also celebrated for her shaping of the Voting Rights Act and passage of Title IX.

The exhibition demonstrates “how important women are, period, in history,” says Lemay. Much work remains to be done, she says. But, if viewers “look at the historic record and see it as a change agent, that is great, that’s what I’m hoping people will do.”

“Votes for Women: A Portrait of Persistence,” curated by Kate Clarke Lemay, is on view at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery through January 5, 2020.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5e/db/5edb241a-9a10-4e10-9c3d-3e93a22e8baf/exhsu171.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/24/17/24171e05-0c0d-4b38-9fee-536fa4559e90/truthr.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f7/e0/f7e050c6-989c-4a79-85a0-bff6069deba3/stoner.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/38/e7/38e7b8e1-104d-4c1c-a7e6-e933dc1473b1/exhsu10.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ee/b5/eeb560ce-3b69-4488-950c-ff8f29dc8576/exhsu86.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0c/c3/0cc34430-26fa-48c2-bfed-50273a94164b/exhsu185.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/05/1e/051e22ea-4140-4c6a-aac8-df5bf0ea65a7/lucretia_mott-r.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)