How World War I Influenced the Evolution of Modern Medicine

Medical technology and roles during World War I are highlighted in a new display at the National Museum of American History

One hundred years ago, when the United States declared war on Germany, it joined the-then most extensive international conflict in the history of the world. The Great War, or World War I, ushered in a new era of technological advancement, especially in the area of weaponry–tanks, machine guns and poison gas made a violent debut on the battlefields in Europe. But alongside this destructive technology came the accelerated development of modern medical tools.

Medical devices and other artifacts from the era are on view in a new exhibit at the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History as part of the institution’s commemoration of the centennial anniversary of the nation’s entry into the war. Alongside four other displays highlighting other aspects of World War I, this collection explores the application of medicine on the battlefield and advances in medical science during the conflict.

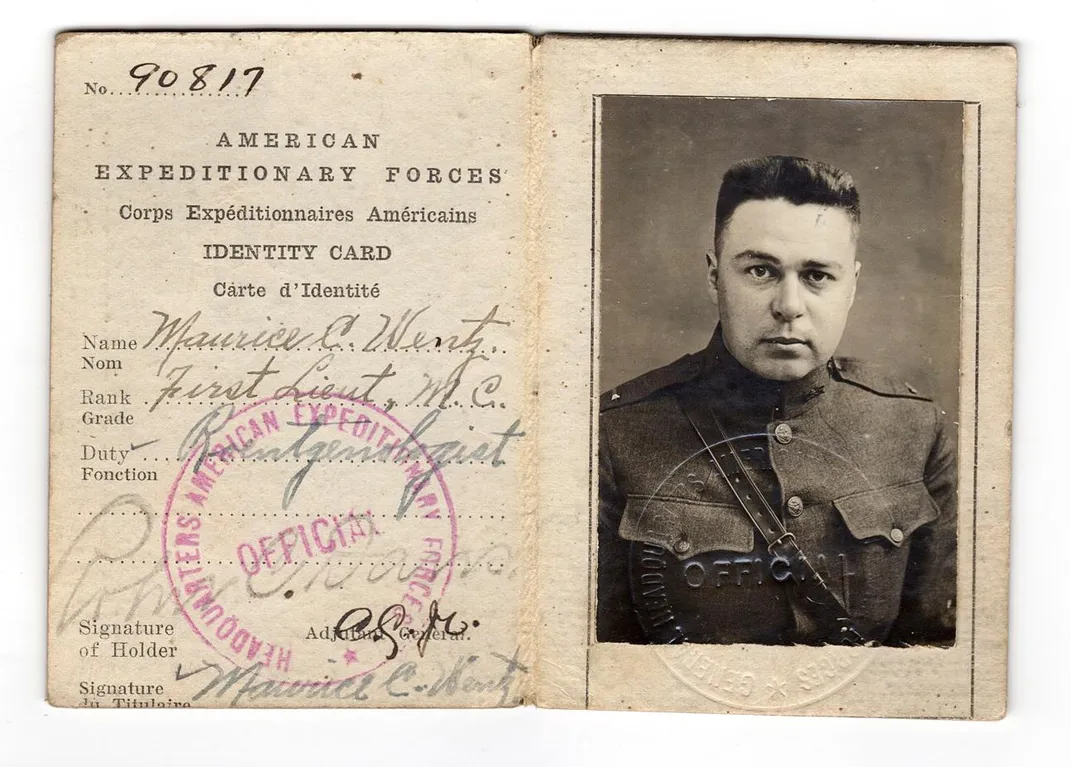

The primary medical challenges for the U.S. upon entering the war were, “creating a fit force of four million people, keeping them healthy and dealing with the wounded,” says the museum's curator of medicine and science Diane Wendt. “Whether it was moving them through a system of care to return them to the battlefield or take them out of service, we have a nation that was coming to grips with that.”

To ensure the health of the millions of soldiers recruited for the war effort, doctors put the young men through a series of tests to assess physical, mental and moral fitness. Typical physical examinations of weight, height and eyesight were measured on a recruitment scale. These physicals accompanied intelligence tests and sex education to keep soldiers clean or “fit to fight.”

On the battlefields, physicians employed recently invented medical technology in addressing their patients’ injuries. The X-ray machine, which had been invented a couple decades before the war, was invaluable for doctors searching for bullets and shrapnel in their patients’ bodies. Marie Curie installed X-ray machines in cars and trucks, creating mobile imaging in the field. And a French radiologist named E.J. Hirtz, who worked with Curie, invented a compass that could be used in conjunction with X-ray photographs to pinpoint the location of foreign objects in the body. The advent of specialization within the medical profession in this era, and the advancement of technology helped to define those specialized roles.

American women became a permanent part of the military at the beginning of the century with the establishment of the Army Nurse Corps in 1901 and the Navy Nurse Corps in 1908, but their roles in the military continued to evolve when the nation entered the war in 1917. Some women were actually physicians but only on a contract basis. The military hired Dr. Loy McAfee, a female doctor who graduated with her medical degree in 1904, as one of these "contract surgeons." She helped chronicle the history of the army's medical department during the war as a co-editor of a 15-volume text that was completed in 1930.

“It was an expanded but limited role for women,” notes Mallory Warner, project assistant in the museum's division of medicine and science. The display documents the different roles women played during the war with a rotating set of women’s uniforms.

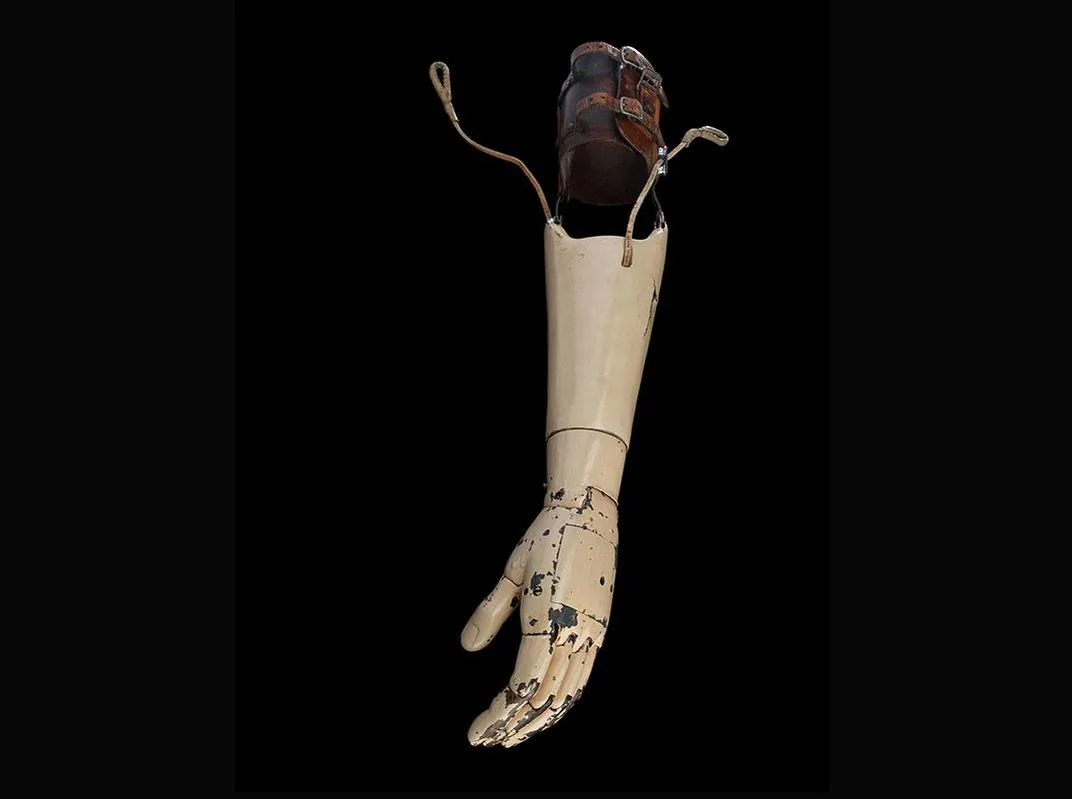

Women found an expanded role particularly in the area of “reconstruction,” or rehabilitation. All of the major countries developed these “reconstruction” programs to treat injured soldiers and send them home as functioning members of society. Occupational and physical therapy were central to these programs and women were needed to walk patients through this rehabilitation.

The warring countries "were very concerned about not just what was happening during the war, but also what was going to happen to their wage-earning male population after the war was over,” says Wendt. Of course, it was critical for the health of soldiers to address their injuries, but it was also essential to heal as many soldiers as possible to help them reestablish the post-war workforce. It was as much an economic issue as it was a health or humanitarian one.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the U.S. was at the forefront of prosthetic design—so much so that the English hired American companies to establish prosthetic workshops in England. One of these American-produced prosthetic arms, called the Carnes arm, is on view in the museum’s display.

As in any war, first response, or first aid, was critical to an injured soldier’s fate. Tetanus and gangrene were serious threats as germ theory was only in its infant stages. It was during the war that doctors began refining the use of antiseptics to offset the risk of infection. Clearly, stabilizing patients upon injury is always crucial in first response, and a leg splint on view in the exhibit is a reminder of the importance of the most basic medical treatments. Splints drove mortality rates down by preventing hemorrhaging.

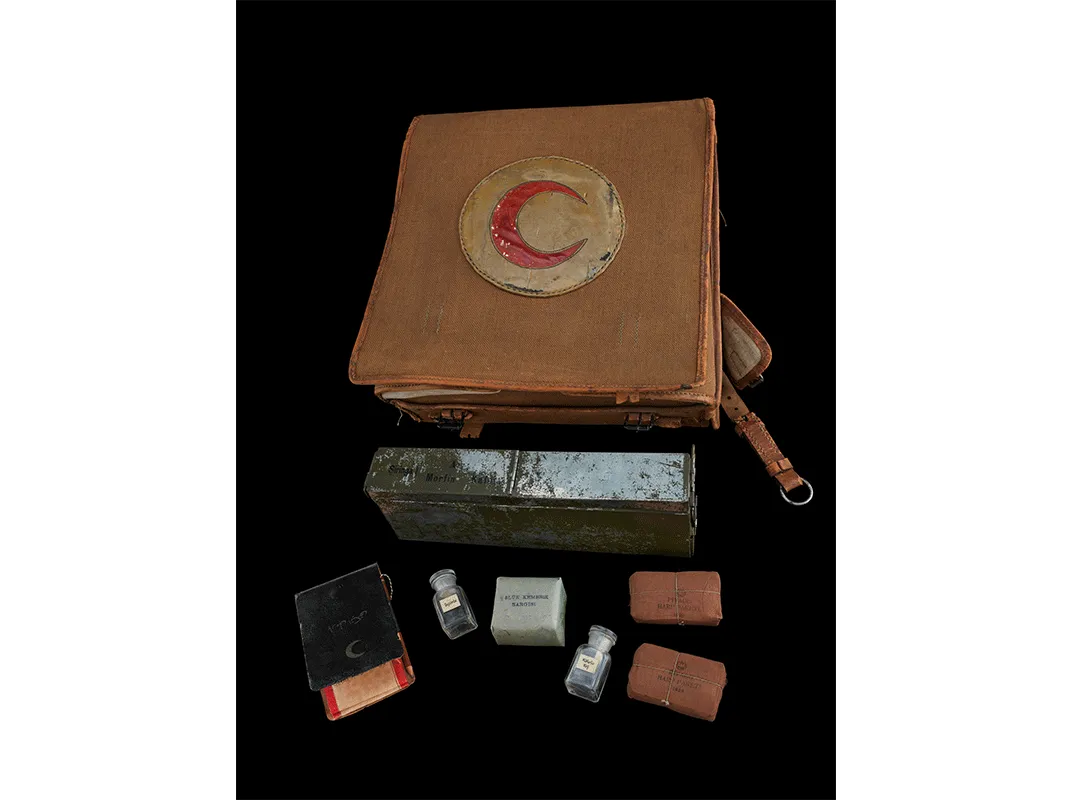

While the display highlights American experiences in the war, it also contextualizes the American experience within a larger global arena with objects from other countries. A backpack from the Turkish army marked with the Red Crescent, the symbol introduced by the Ottoman Empire in the 1870s as the Muslim alternative to the Red Cross symbol, and a chest from an Italian ambulance are on view.

All of the objects, long held in the museum’s medical or armed forces collections, make their public debut alongside the museum’s World War I commemoration with exhibits on General John J. Pershing, women in the war, advertising and art by soldiers. The displays remain on view through January 2019 and accompany a series of public programs at the museum.

"Modern Medicine and the Great War" is on view April 6 through January 2019 at the National Museum of American History.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_0154.JPG.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_0154.JPG.jpeg)