Meet the Iconic Japanese-American Artist Whose Work Hasn’t Been Exhibited in Decades

A reexamination of the inventive artist, who blended American and Japanese traditions, brings rarely seen works from around the world to the Smithsonian

:focal(219x323:220x324)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20/80/208022c2-b0d8-48d3-8891-1ed51c955b8d/aaafedeartp143722.jpg)

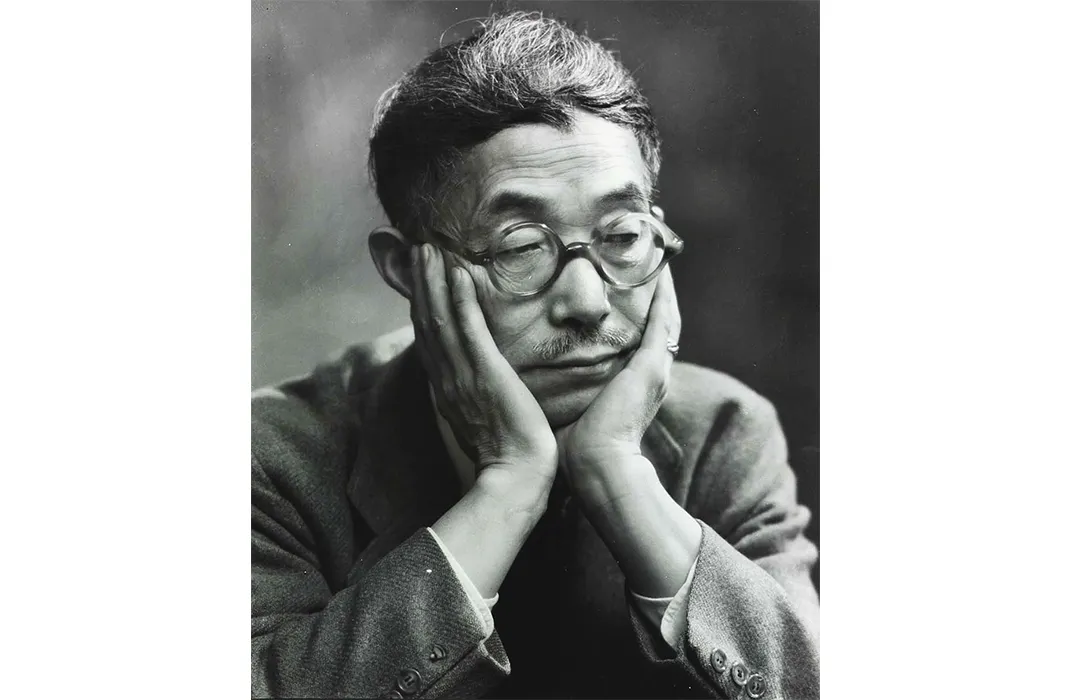

Born in 1899, Yasuo Kuniyoshi first came to the United States from Japan in 1906 at the age of 16. He had no intention of either staying nor becoming an artist. But after taking classes at New York’s Independent School and the Art Students League, where he later taught, he found he had a knack for painting.

In his lifetime his sometime enigmatic work became as well known as contemporary modernists Georgia O’Keeffe and Edward Hopper, with prestigious shows and even earning a memorable presidential review—"If that's art, I’m a Hottentot, " Harry S Truman once said of his work.

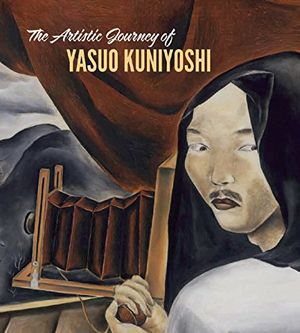

But after his death in 1953, he became less well known. A rising interest in Japan meant a lot of his work ended up overseas. The retrospective “The Artistic Journey of Yasuo Kuniyoshi” at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C., is the artist's first comprehensive exhibit in the United States in more than 65 years. (The exhibition is also available online.)

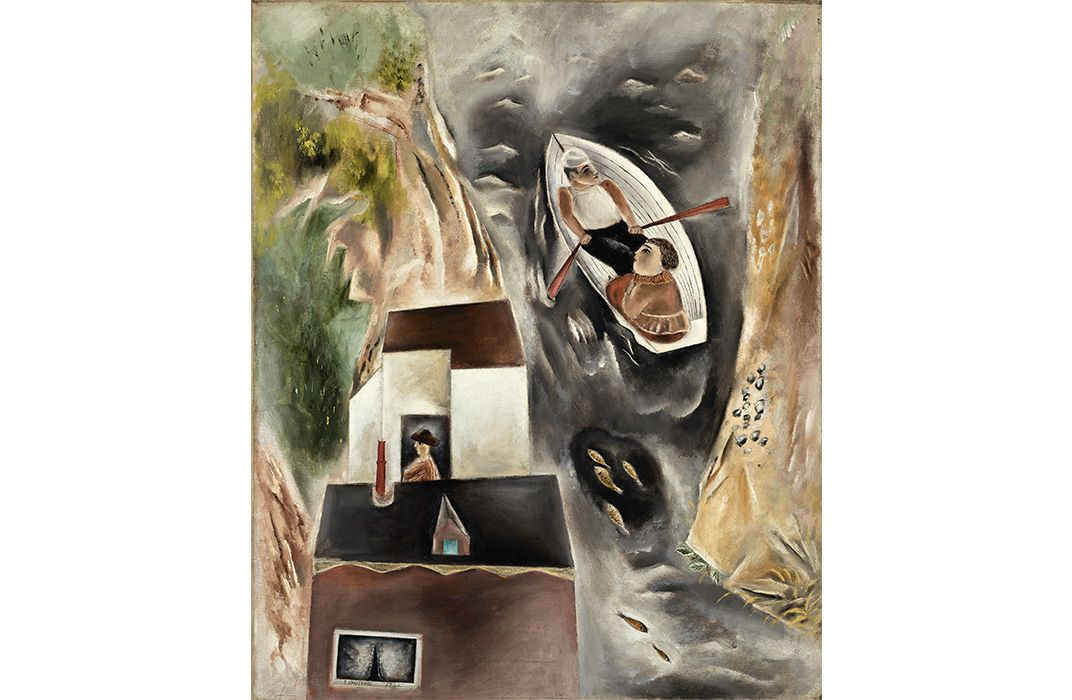

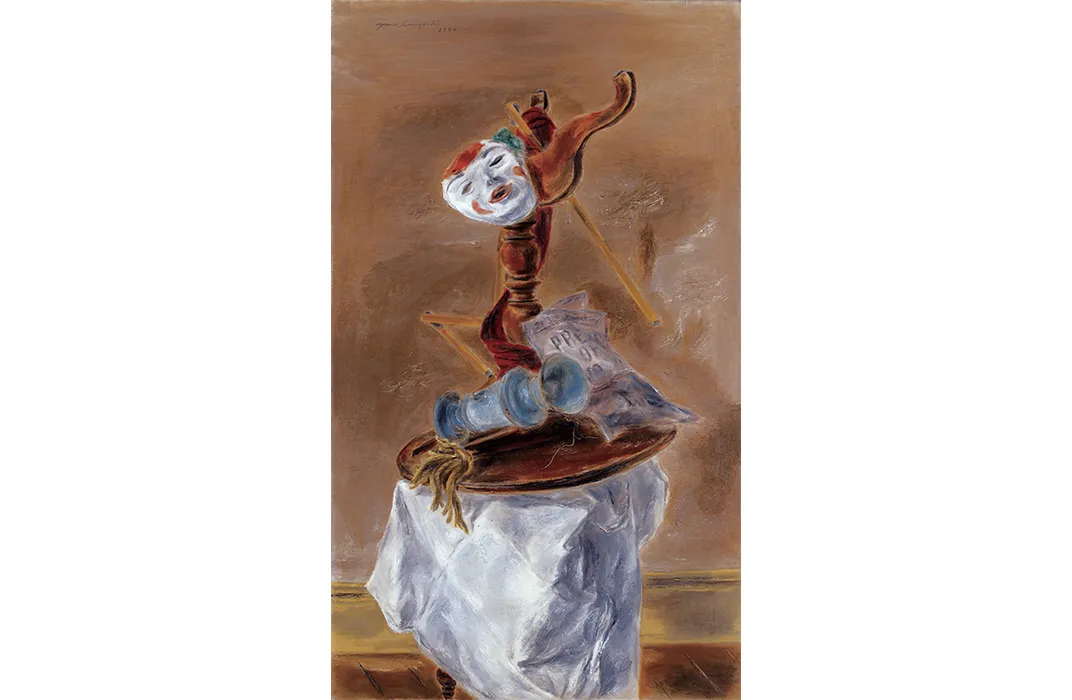

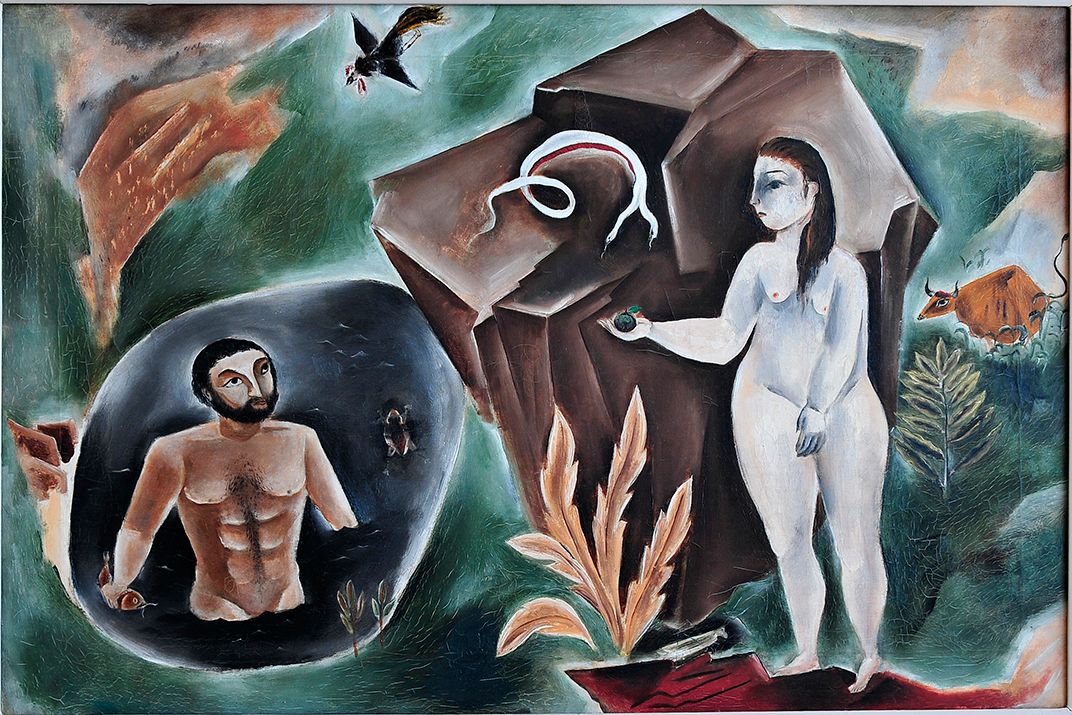

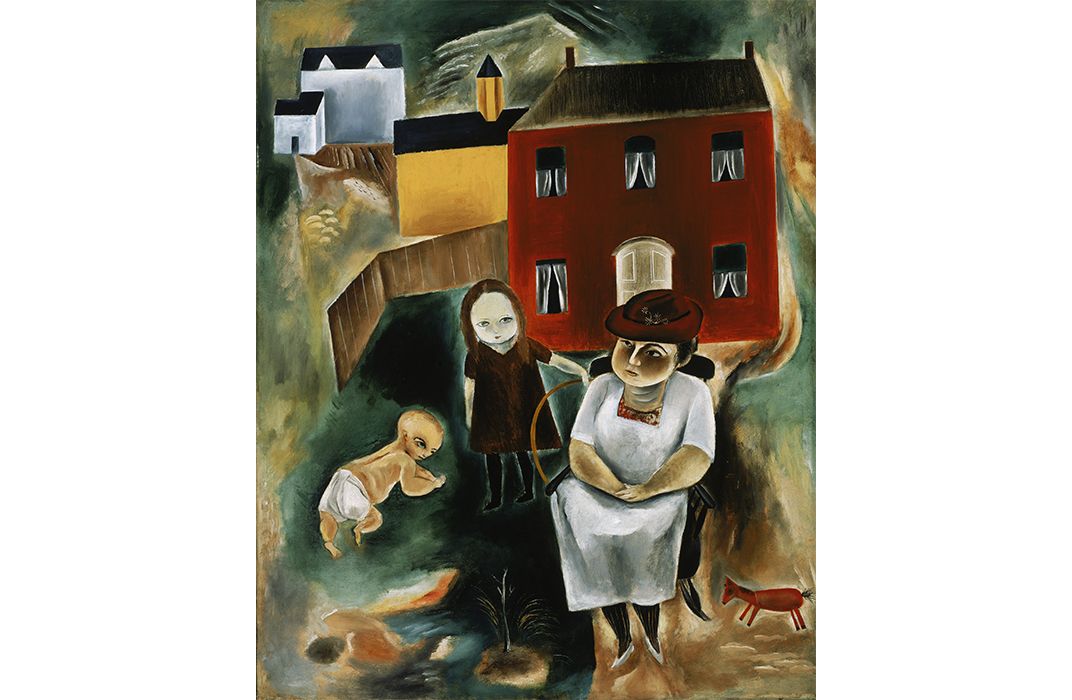

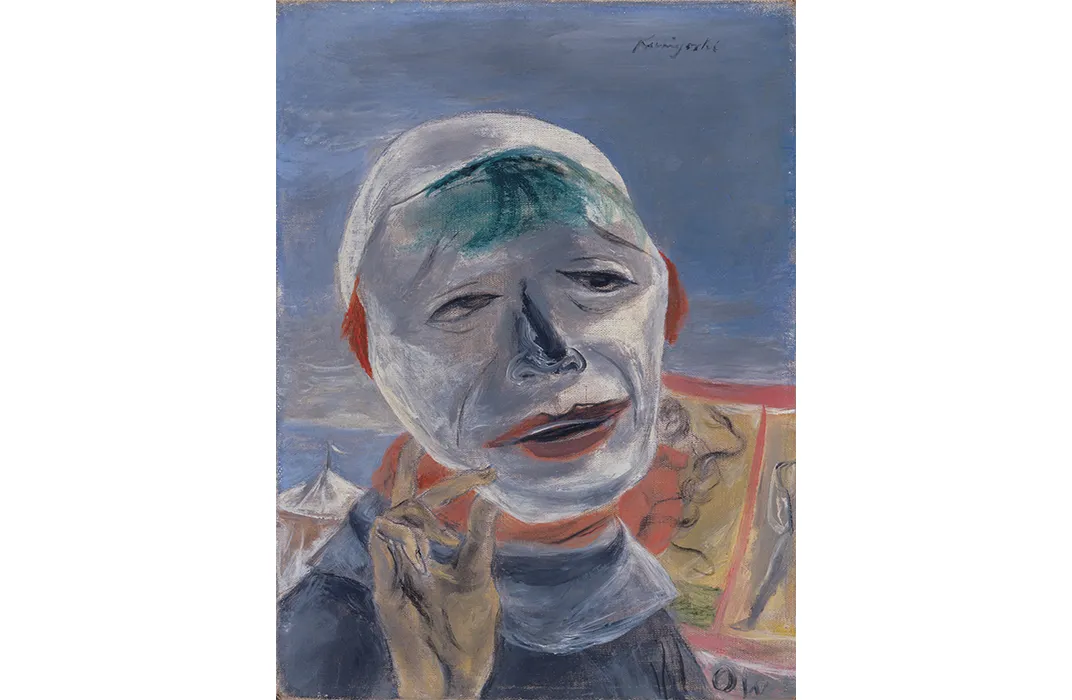

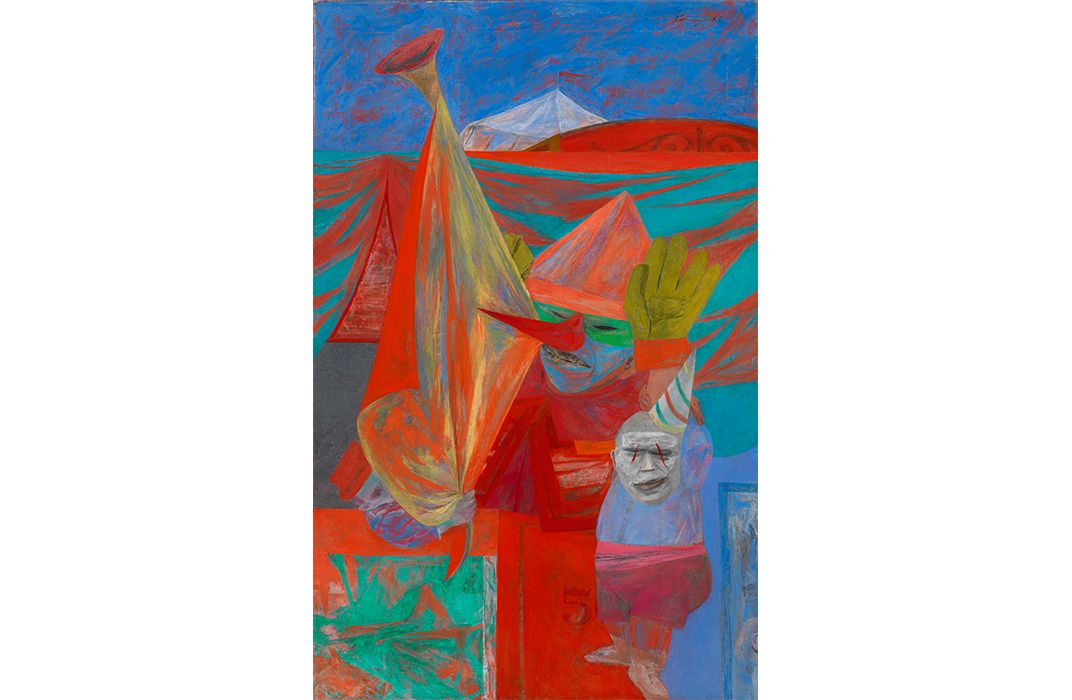

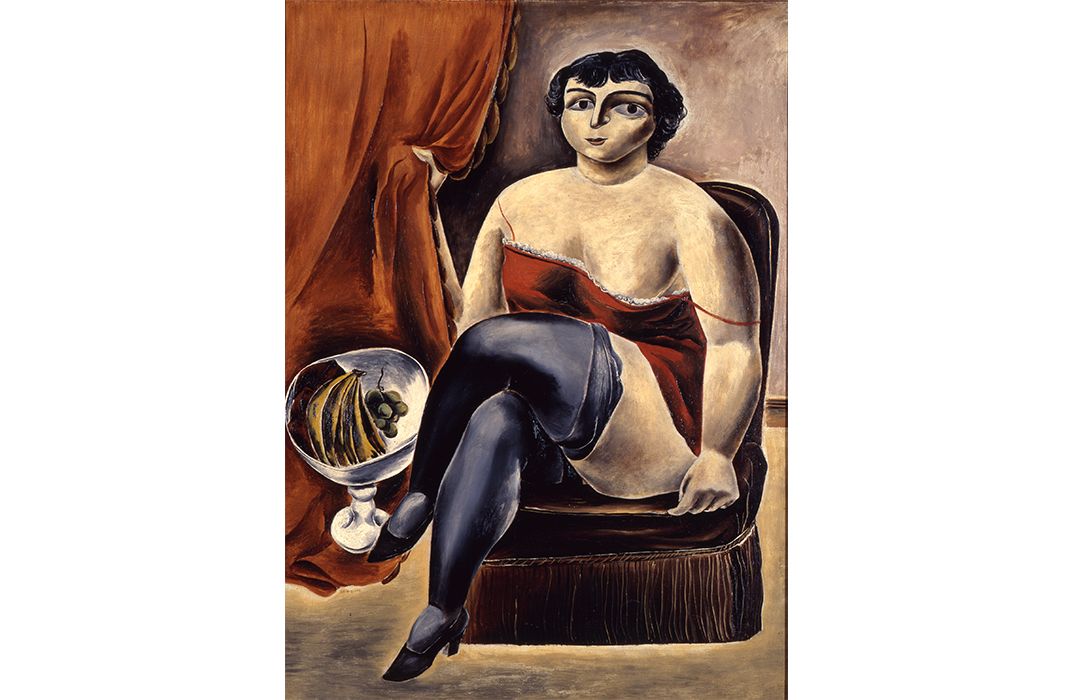

For many, it will be an introduction to a singular, innovative painter who blended the bleak ethos of American modernism with symbols of Japanese subjects, and flirtations with an European surrealist sensibility in his portraits of circus figures, wide-bodied nudes and vivid nightmares.

“It’s high time to review his work and take a look at it with fresh eyes,” says Joanne Moser, the museum's deputy chief curator, who co-organized the exhibition with Kuniyoshi scholar Tom Wolf.

“He’s better known today in Japan than the United States,” Moser says, “though he considered himself an American artist.”

He was never an official citizen, though, and when he married an American woman in 1919, she lost her citizenship too (and her family disowned her).

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Kuniyoshi was not forced into an internment camp, as were many Japanese Americans on the West Coast, but he was nonetheless branded an enemy alien, his bank account impounded, his freedoms clipped.

“He had to give up his camera and his binoculars,” Moser says. “His travel was restricted.” And though these hardships were not explicitly dealt with in his work, they are strongly suggested in the exhibition.

A description accompanying the 1924 oil Child Frightened by the Water suggests it’s not the water actually creating the fear. The label asks: “Could Kuniyoshi also have felt anxious as the U.S. government enacted the Asian Exclusion Act of 1924, which made it illegal for people from Asia to immigrate to the United States?”

A circular background behind the pen and ink nude in Sleeping Beauty “suggests that his marriage was an island of happiness and security in an otherwise difficult environment, at a time when anti-immigrant feelings in the country were strong.”

Moser says a lot of these suggestions are speculation. Because of its enigmatic nature “there’s a lot of room for explanations in Kuniyoshi’s work,” she says.

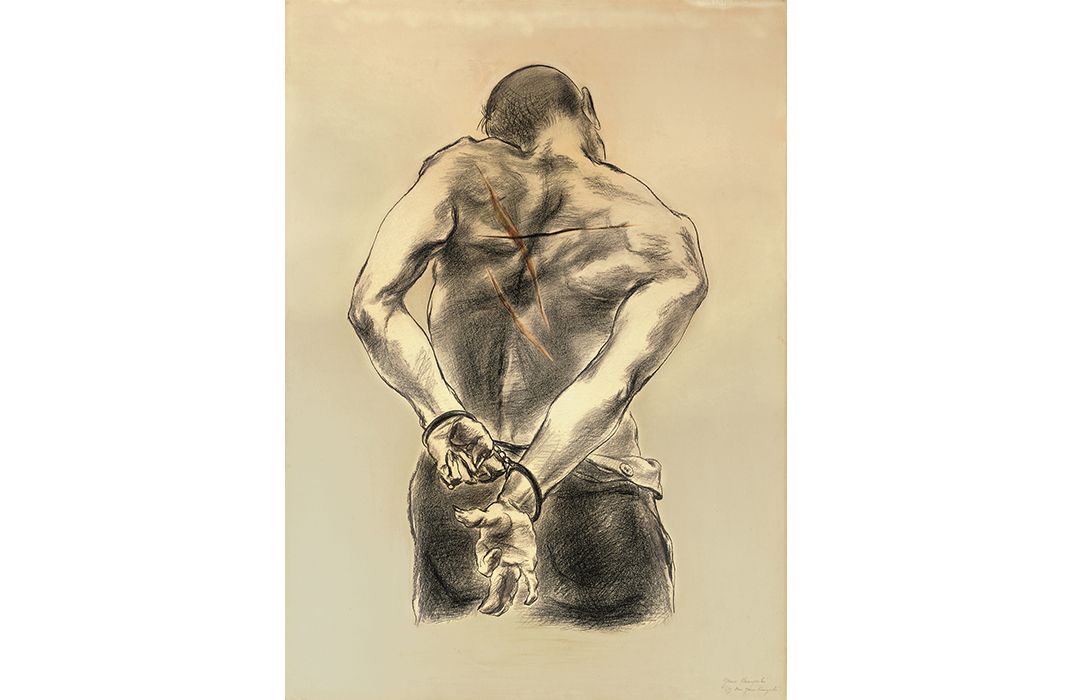

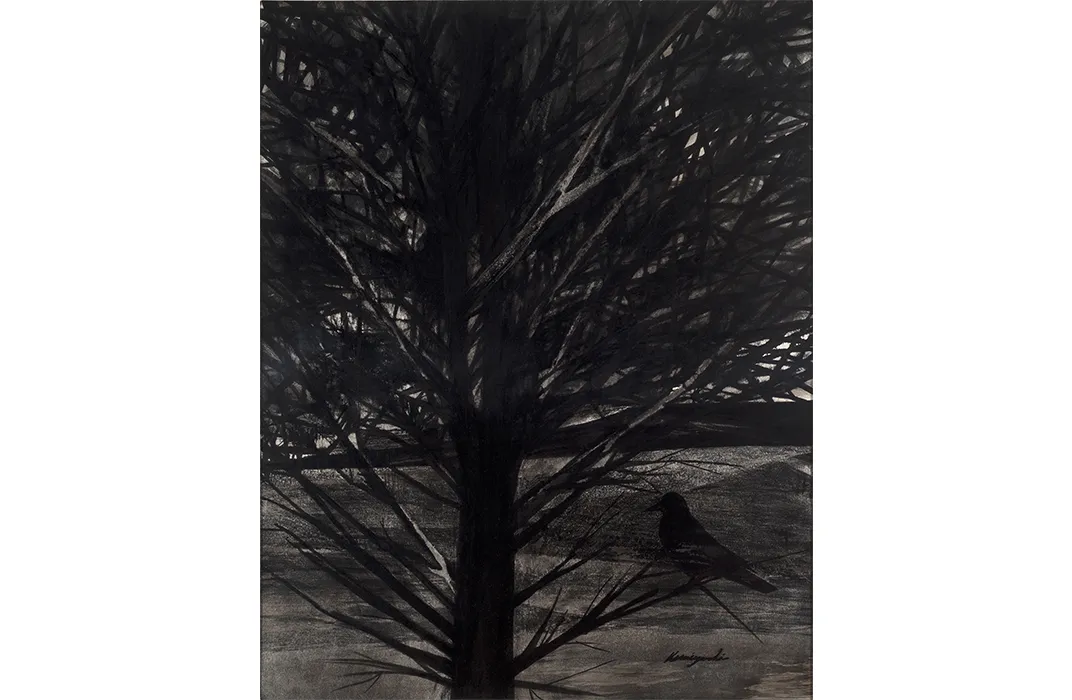

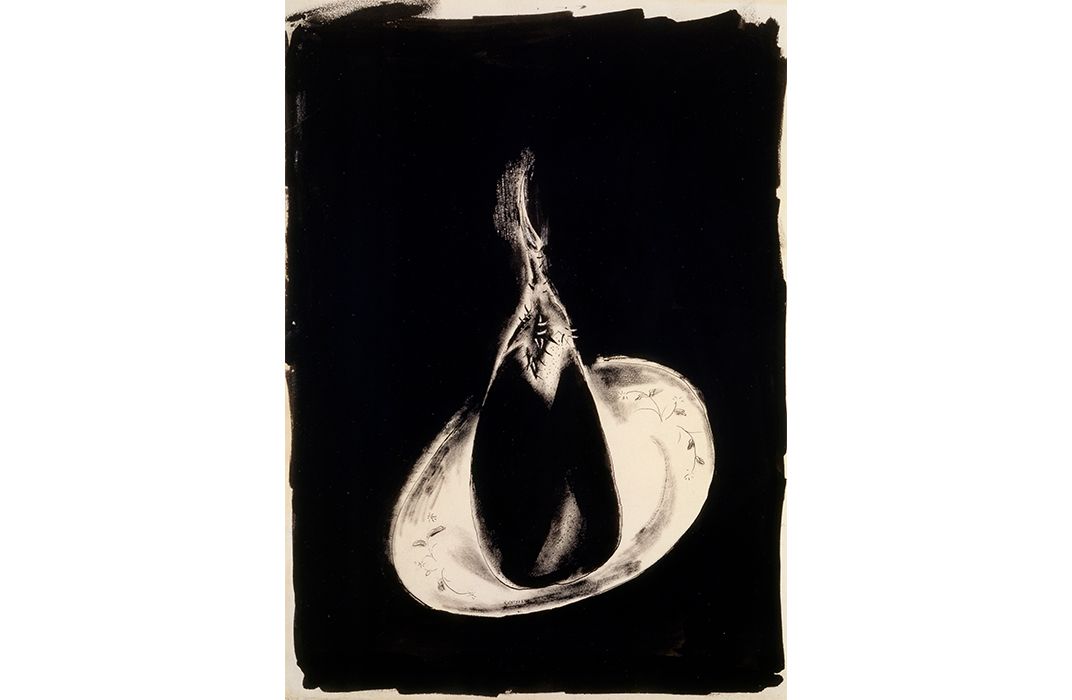

What was enigmatic, fraught with unclear symbolism or even humorous in his earlier paintings became stark rendering during World War II when, to show his patriotism for his adopted country, he drew proposals for posters showing the brutality of Japanese forces, depicting torture, a hanging and waterboarding. It was as unusual a turn for his work as would be a later group of paintings in the early 1950s that used a riot of garish, almost acrid, colors. His dark, brooding black and white pen drawings just before his death in 1953 returned to the fish imagery that had been part of his work for years and a staple of traditional Japanese art.

Kuniyoshi’s innovative genius came in his blending of Japanese idioms with American folk art influences as well as that of European modernism. ""His work is a distinctive expression of many strands of early twentieth-century American art flavored with his sly humor, idiosyncratic imagination, personal experience, and subtle references to his Japanese heritage," writes Moser in an essay.

It was during early visits to an artists colony in Ogonquit, Maine, sponsored by his friend and patron Hamilton Easter Field, that led Kuniyoshi to the kind of flattened spaces, squat figures and diminishing of single point perspective that marked his work, says Wolf, a professor of art at Bard College.

A visit to Europe in 1925 gave a more provocative tone to Kuniyoshi's work, as well as an interest in circuses. His 1925 Circus Girl Resting gained wide renown when it was chosen as part of a 1947 U.S. State Department funded exhibition “Advancing American Art,” a sort of traveling show of cultural diplomacy that also featured work by Hopper, O’Keeffe, Stuart Davis and Marsden Hartley.

But the press decried the modernist choices, with Look magazine howling in a headline, “Your Money Bought These Pictures.” Truman, referring to Kuniyoshi’s piece in particular, said “the artist must have stood off from the canvas and thrown paint at it," adding his garrulous commentary, "If that’s art, I’m a Hottentot.” The traveling show was canceled and the art sold at a loss.

Still, Kuniyoshi remained one of the most highly celebrated artists of his day. He was the first living artist chosen to have a retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1948.

“He was collected in his lifetime,” Moser says. Indeed, the 66 pieces in the 65-year retrospective comes from such renowned institutions as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Museum of Modern Art and the Phillips Collection as well as a number of Japanese public and private collections.

But even with fame, Kuniyoshi eventually ran into the dominance of then-rising abstract expressionism, Moser adds. “The art world had moved on.”

As tortured as his life is interpreted to be in the retrospective, the artifacts in an accompanying exhibit, “Artist Teacher Organizer: Yasuo Kuniyoshi in the Archives of American Art” down the hall at the Lawrence A. Fleischman Gallery through July 10 show him to be a well adjusted member of his artistic community, pictured at social gatherings and costume galas (including, at one, where many artists friends dressed like him).

Kuniyoshi wrote, in a letter to fellow painter George Biddle shortly after Pearl Harbor, “A few short days has changed my status in this country, although I myself have not changed at all.” Letters of support for Kuniyoshi after he was declared an enemy alien are on display as are his applications for domestic travel for professional reasons.

Whatever the analysis of Kuniyoshi’s enigmatic work, the artist may have given a hint at his intent in unpublished autobiographical notes from 1944: “If a man feels deeply about the war or any sorrow or gladness, his feeling should be symbolized in his expression, no matter what medium he chooses.”

"The Artistic Journey of Yasuo Kuniyoshi" is on view through August 30, 2015 at the Smithsonian American Art Museum at 8th and F Streets in Washington, D.C. “ Adjacent to the Kuniyoshi show in the Lawrence A. Fleischman Gallery through July 30, 2015 is the archival show entitled "Artist Teacher Organizer: Yasuo Kuniyoshi in the Archives of American Art.”

The Artistic Journey of Yasuo Kuniyoshi

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/12/d4/12d412e5-3e0d-4f5d-a389-6d8e7ab0853a/kuniyoshimraceweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fc/f1/fcf1e918-3393-46b4-898d-6e8c2d396d91/kuniyoshiwaitingweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/67/08/67085eea-e9f2-425a-9c0e-6f9ad82243d0/kuniyoshiselfportraitweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cf/39/cf398fc7-5ad4-45f9-badd-ec3010ccd6ca/kuniyoshiselfportraitasaphotographerweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)