If Clouds Could Make Music, What Would it Sound Like?

How an engineer, video analyst and musician created a pioneering artwork that makes music from the sky

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/02/09/0209d2aa-3a82-4688-81d1-3b43498497cf/cloudmusic.jpg)

When Robert Watts, a former Navy engineer, moved to New York City in the 1950s to pursue art, he wasn’t buoyed by the Avant-garde movement sweeping Manhattan. He felt trapped.

The Iowa native, who spent the days and nights of his childhood gazing at the open sky, felt dwarfed by the city’s skyscrapers and blinding lights. In his new city, he couldn’t see the sky—but started to think perhaps he could help people hear it.

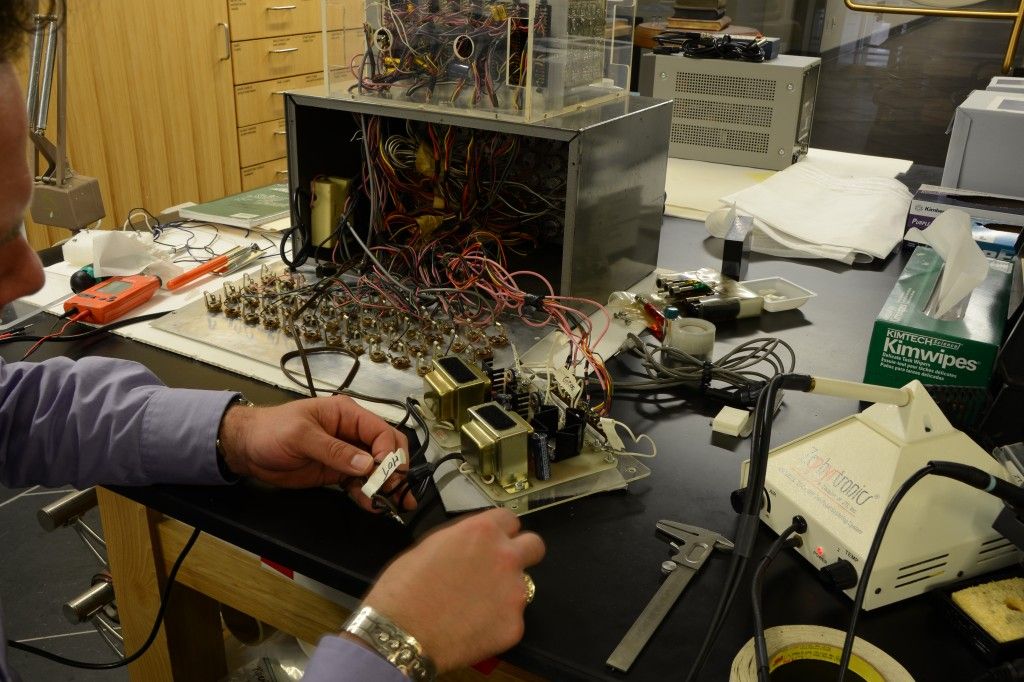

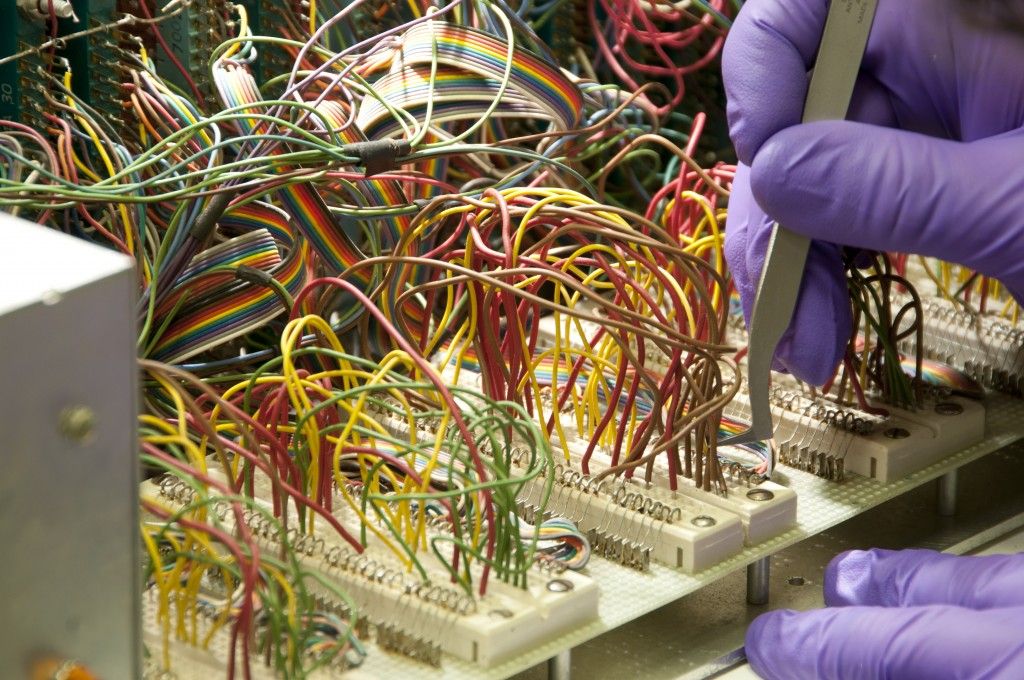

Along with video engineer Bob Diamond, a former NASA analyst, and composer David Behrman, an experimental musician, Watts created a video system that analyzes six points in the sky, connecting them to a synthesizer and playing the harmonic voices through speakers.

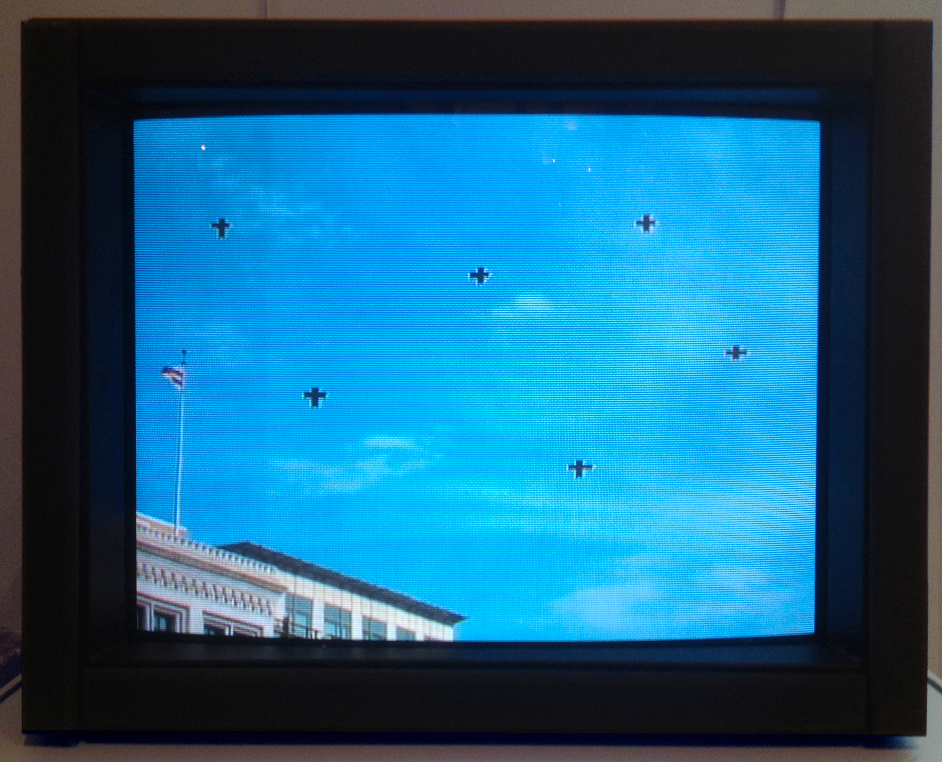

Now, the pioneering work has come to the Smithsonian American Art Museum. It hangs in a corner window of the north-facing Lincoln Gallery, capturing the clouds that race above the Chinatown neighborhood of Washington, D.C., and playing back their haunting, hollow tones on six speakers.

The speakers staggered across the walls correspond with the video points—marked for visitors on a television that mirrors the camera viewfinder—so “you’re listening to video and watching sound,” says curator Michael Mansfield. “It’s composed in real time. . . .which makes it very compelling.”

On a recent calm, cloudy day, layered harmonies floated across the gallery space. But the system is weather-dependent, Mansfield says. Changes in the atmosphere—like storms, high pressure, waving flags or the occasional flock of birds—will energize the score, making the tempo or tones change more quickly.

The music sounds like a cross between singing whales and an early Nintendo soundtrack; archaically digital, not refined like the autotune that’s taken over contemporary radio. It’s not sweet or melodic; it’s dissonant and hard to place, as it doesn’t rely on the scales typically found in Western music.

The project is “digital” in the most skeletal sense; it was conceived pre-computer in 1970s. Watts and Behrman built their system from scratch, wiring six crosshairs on the camera to a mechanism that then interprets the data and sends it to a synthesizer programmed with pre-selected, four-part chords. Changes in the sky captured by the camera cause harmonic changes in the sounds played through the speakers.

When Watts set out to make this project, technology like this was only beginning to exist, Mansfield says. At the time, closed circuit television—the kind used in surveillance to send signals to specific monitors instead of into the open air—was relatively rare.

The piece debuted in 1979 in Canada, and went on to travel the world, from San Francisco to Berlin and beyond. In each of those places, the inventors positioned the camera over an iconic part of the city so visitors would know the music was authentic: When the work was at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, it was pointed at a water tower across the street, Mansfield said; in Washington, it captures a fluttering DC flag on a nearby rooftop.

The tour was part of a broader “really intense enthusiasm to break the barriers between painting and sculpture and art and performance, theater and traditional music” and electronics, Mansfield says, that started to sweep the art scene during that decade.

It put forward some “really unique and new ideas about technology and gallery and art space,” Mansfield says. The piece pushed the envelope on what most people had come to think about art galleries; it helped prove that people could hear and feel and interact with art, not just see it.

The system will stay put in the Lincoln Gallery for now, but Mansfield hopes he can incorporate the work into different exhibits in the future. The acquisition also includes drawings and photographs that chart its development, along with an archive of scores from the synthesizer, which capture the “sound of the skies” above cities across the world.

“There are so many ways to reconceive this work,” Mansfield says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erica-hendry-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erica-hendry-240.jpg)